by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 25, 2016

Summertime and swimming at the beach just go together naturally in Florida with our state’s more than 1,000 miles of coastline. Many fond memories are created along these salty margins and the Panhandle region of the state has some of the top-rated beaches in the world. It is a great place to experience a relaxing, cool dip in the Gulf of Mexico on a balmy summer day. One thing to be aware of though is the possibility of an encounter with one of the Gulf’s “stinging” inhabitants and what to do if this occurs.

The Moon Jelly is a Common Inhabitant Along Panhandle Shores. Photo courtesy Florida Sea Grant

There are actually several different organisms that have the capability to sting. This is primarily their mechanism for capturing food but it may also serve to deter predators. Most belong to a group of organisms called “Cnidarians,” which includes the jellyfish. Most jellyfish are harmless to us and are important food sources for many other marine creatures, including some sea turtles, fish and even other jellies! Some species are even dried, shredded and eaten by humans. However, there are several types of jellyfish that will inflict a sting when brushed against and some that are actually a serious hazard. Keep in mind that people also react differently to most venoms, exhibiting varying degrees of sensitivity. The most dangerous types include some of the box jellyfish species (visit HERE for general map of worldwide jellyfish fatalities), and the blue-colored Portuguese man-o-war, which is sometimes common on our shores after sustained southerly winds during summer. A few of our locally common species that cause pain but of a generally less-severe nature include the moon jelly, sea nettle, and cannonball jellyfish. We even have some species of hydroids that look very much like a bushy brown or red algae. They are usually attached to the bottom substrate but when pieces break off and drift into the surf they can provide a painful encounter.

If you are stung there are a couple of things you can do to help and a couple of things you should not do. First, move away from the location by getting out of the water so you don’t encounter more tentacles. Carefully remove any visible tentacle pieces but not with your fingers. You should also change out of swimwear that may have trapped pieces of tentacles or tiny larval jellyfish against the skin. Do not rinse the area with fresh water as this causes the remaining stinging cells to fire their venomous harpoons. If symptoms go beyond a painful sting to having difficulty breathing or chest pain you should immediately call the Poison Information Center Network at 1-800-222-1222 or call 911.

Another thing to watch for in areas where public beaches display the beach warning flag system is a purple flag. This flag color at the beach indicates dangerous marine life and quite often it is flown when jellyfish numbers are at high levels. All of this is being written, not to scare you away from our beaches, but to help you enjoy our beautiful coastline with a little better understanding of what is out there and what to do if you happen to have a brush with a jellyfish. The vast majority of encounters are a minor irritation in an otherwise pleasant experience.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 4, 2015

Yep, but do not get to alarmed just yet… it is not the same species as the famous one from Australia. That said… who is this new invader to our waters and is it of concern?

This Four-handed box jelly was found near NAS Pensacola in 2015.

Photo: Courtesy of Robert Turpin

According to NOAA and the University of California at Berkeley there are between 20-50 species of box jellies from around the world. Their distinct shape, often called “cubomedua”, places them in their own family. Most of the “medusa” jellyfish we know are in a group called “scyphozoans” but box jellies differ in several ways.

- Their shape – the “box” shaped and their tentacles are clustered into four groups on the corners of the “box”.

- They are very good swimmers – most medusa can undulate their “bells” and move but they are planktonic (drifters) in the ocean currents. Box jellies are very strong swimmers. They can move against currents, tend to swim below the surface more (often collected in shrimp trawls), and have been clocked at top speeds of 4 knots! (This is very fast for a jellyfish).

- They do have eyes. They know where they want to go, can avoid colliding with piers, and have been known to even swim away from collectors trying to catch them. Not typical of our locals jellyfish. Lacking a central nervous system like ours, science is not sure how they see, or what they see, but they do.

Box jellies are found in all tropical seas, including the south Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico. They range in size from less than an inch to about 8 inches, with tentacles extending as far as 10 feet behind. Breeding in this group is interesting. Males will place their tentacles inside the bell of the female and deposit sperm. The female will then fertilize her eggs and release planktonic larva called planula. These planula will drift in the currents for a short period before metamorphosing into a flower-like creature called a polyp. Polyps are sessile (non-swimming) and attach to hard structures on the ocean floor. Here they can move and adjust to feed with their extended tentacles and can actually produce more polyps by budding. After a period of time each polyp will metamorphose into a swimming medusa, the box jelly we know and love. As already mentioned, they swim with purpose hunting small fish and invertebrates. They do have their predators. Certain fish and sea turtles are known to consume with no ill effects.

They all possess a very strong toxin which is quite painful. The most toxic of the group is Chironex fleckeri, the famous one from Australia. This jellyfish has been listed by many, including NOAA, as the most venomous marine animal in our oceans. It has certainly caused death in their waters. The majority of the lethal box jellies live in the Indo-Pacific. So what about Florida?

I am aware of two species that have been found here. The “Four-handed Box Jelly” (Chiropsalmus quadrumanus) and the “Mangrove Box Jelly” (Tripedalia cystophora). The Four-handed box jelly is the larger of the two, and the one pictured here. The Mangrove Box Jelly typically lives in the Caribbean. The first reported in south Florida was in 2009 near Boca Raton but they have since been reported in the Keys and along the Southwest coast of Florida. This is a small box jelly (about 0.25” in diameter) and seems to prefer the prop roots of mangrove trees.

The Four-handed box jelly can reach almost 5” in length with up to 10’ of tentacles attached. It is more widespread in Florida, though more common on the Atlantic coast then our own. One was brought to me about 6 years ago. The person found it next to pier at Quietwater Boardwalk, in the evening, swimming around the lights shining in the water, it was near Thanksgiving also. The one pictured here was seen by a local surfer and by Robert Turpin (Escambia County Division of Marine Resources) last week. Both sightings were near NAS Pensacola and may have been the same animal. This box jelly has the same characteristics as others – box shape, clustered tentacles, and very painful sting. The surfer who brought me the one from 6 years ago was stung by it. He said the pain brought him to his knees… so do not handle this animal if you see one. There was a report of a small child who died after being stung by one in 1991. However there are reports of young kids dying from the Portuguese man-of-war as well. Lesson here… treat it with caution.

These box jellyfish are not the deadly ones known from Australia, and it is certainly not common here – preferring to stay in the open ocean more than nearshore, but it is an animal all should know about and avoid handling if encountered.

More resources on this animal:

http://www.sanibelseaschool.org/experience-blog/2014/9/24/5-types-of-jellies-in-the-gulf-of-mexico

http://beachhunter.net/thingstoknow/jellyfish/

http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cubozoalh.html#Active

by Erik Lovestrand | May 29, 2015

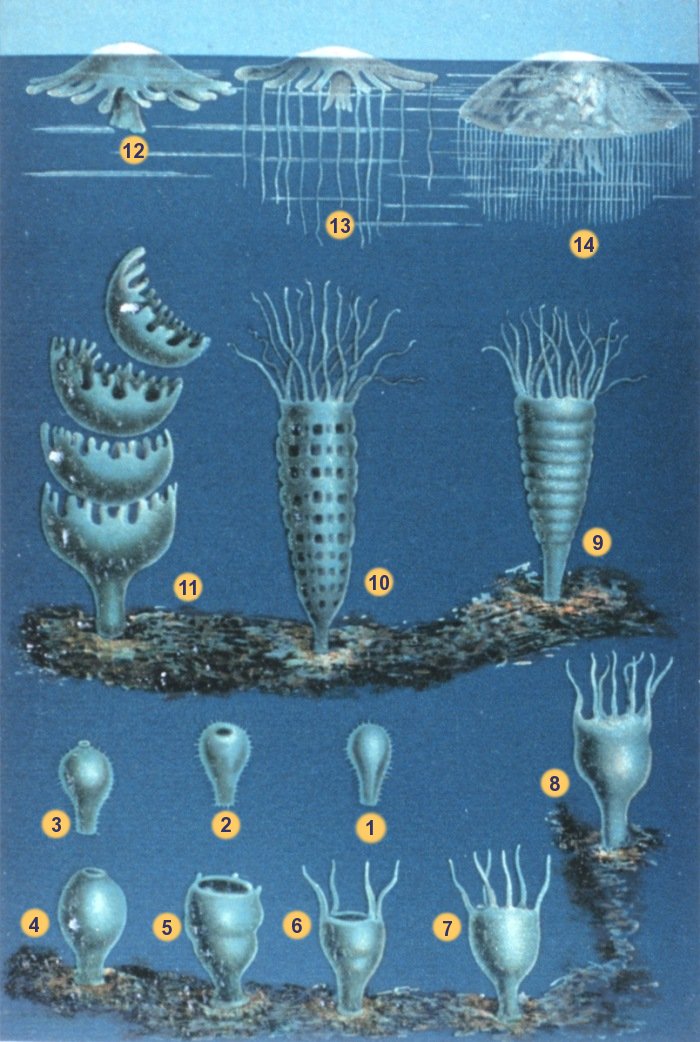

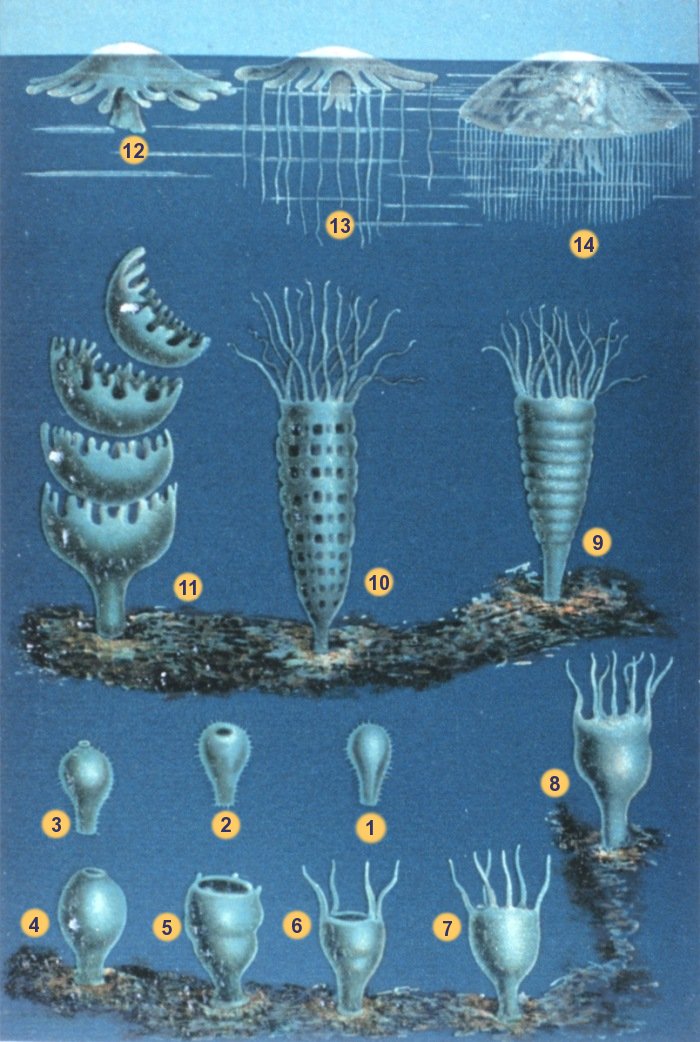

![Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/files/2015/05/Schleiden-meduse-2-202x300.jpg)

Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“Ouch, something just stung me.” This is a common phrase to hear someone say (I’ve heard myself say it) while enjoying the otherwise soothing waters along our beautiful Gulf Coast. We host an amazing variety of marine organisms that possess the ability to sting when contacted. I’m referring to organisms in the phylum Cnidaria (pronounced “ni-dair-ee-ah”), which includes about 10,000 species that have been identified. There is general agreement on the classification of five different classes of cnidarians, all of which have stinging cells, but most of which are not dangerous to humans. These include Class Anthozoa (anemones and corals), Class Cubozoa (box jellyfish), Class Scyphozoa (true jellyfish), Class Staurozoa (stalked jellyfish) and Class Hydrozoa (hydroids i.e. Portuguese man o’ war). I’m always intrigued by the origin of scientific names so here is a slight tangent for you on the group names (Cnides: from the greek meaning nettle)(Antho: flower-like; Cubo: cube-shaped; Scypho: cup-shaped; Hydros: sea serpent; Stauro: cross-shaped). The term “zoa,” of course, refers to animals.

Most of the time you are stung in our local waters it involves the classes Hydrozoa or Scyphozoa. The Hydrozoans are a complex group of organisms but most species go through two distinct stages during their life cycle. The hydroid stage takes the form of a polyp which is composed of a stalk and tentacles at the end. Polyps can be single but are often colonial, connected by tube-like structures. Most polyps are specialized for feeding but others are used to reproduce. Reproductive polyps lack tentacles but have many buds which form the medusa stage of the organism for reproduction purposes. Medusae of the hydroids are similar in design but typically smaller than the medusae of the true jellyfish. Some hydroids also have specialized defensive polyps with numerous stinging cells and one species even has a specialized polyp that develops into a large balloon-like float that the others attach to (the man o’ war). There is one specific type of hydroid in our area that closely resembles a piece of branching brown algae, such as Sargassum. The polyps are scattered along the branches and when brushed against they fire their nematocysts (stinging cells) producing a painful sting. The burning sensation can last for several minutes and you would have sworn the only thing around you was a harmless piece of drift algae.

The true jellyfish, of Class Scyphozoa, also go through a polyp and medusa stage. The polyps of this class are typically single and settle to the bottom as larvae and attach themselves. Over time the polyps mature and produce other polyps by budding, or bud medusae off their upper surface. These jellyfish medusae are microscopic at this stage and many take years to reach maturity, complete with a cup-shaped (scypho= cup shaped) bell and tentacles hanging beneath.

The subsequent lives of these translucent marine creatures is no less intriguing than the processes involved in their development. Check out this website from the Smithsonian for more great information. The next time you feel the burn of a host of nematocysts injecting you with their potent venom, I dare you to stop for just a second to be amazed by the fascinating creature that you have just met. If you can pull this off you are well on your way to becoming the quintessential nature nut! Click here for helpful information if you are stung.

![Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/files/2015/05/Schleiden-meduse-2-202x300.jpg)