by Gary Knox | Oct 28, 2014

Figure 1. Paraná pine has a narrow, pyramidal form when young.

Paraná Pine, Araucaria angustifolia:

An ancient-looking conifer for modern landscapes

Paraná pine is a primitive-looking conifer valued for its unusual horizontal branching, sharply pointed triangular needles and neat, symmetrical form. The primitive appearance of this evergreen tree results from its resemblance to and relationship with an ancient group of conifers that dominated forests more than 65 million years ago.

Not a true pine, this dark green tree has a narrow, pyramidal shape when young. Paraná pine is considered fast-growing, and a tree planted at Gardens of the Big Bend in Quincy, Florida, reached a height of 30 feet and a width of 14 feet in eight years (Fig. 1).

Paraná pine reaches a mature size of 60 to 115 feet after 50 to 90 years or more in forests of southern Brazil. As it approaches maturity, the lower branches gradually die and the tree develops a dramatic dome shaped crown that somewhat resembles a candelabra due to upward pointing branch tips. Paraná pine is considered a large, long-lived tree. Fully mature trees may be 140 to 250 years of age, have heights up to 160 feet, and trunk diameters exceeding three feet (Fig. 2).

This evergreen conifer has distinctive sharp-pointed, tough, scale-like needles (Fig. 3). The dark green needles are triangular shaped and about 1 to 2.5 inches long. Needles tend to be tufted at outer ends of stiff, horizontally held branches. Needles persist for up to 15 years and cover all plant parts except the trunk and major branches. The stiff, sharp needles make the tree and branches difficult to handle, while also acting as a deterrent to deer feeding and other animal predation as well as foot traffic.

Figure 2. Closeup of the rough bark of Paraná pine.

Paraná pine is usually dioecious, meaning male and female flowers are borne on separate plants. Pollen cones are oblong, up to seven inches long and about one inch wide at the time of pollen release. Wind carries pollen to female plants bearing seed cones. Young female trees begin to set seed between 12 and 15 years of age. After pollination, seed cones mature about 18 to 36 months later, usually in fall. Seed cones are brown, globe shaped, 7 to 10 inches in diameter, and are usually found in the upper canopy of trees. Each cone holds about 100 to 150 two inch nut-like, narrowly winged seeds (Fig. 4). Cones fall when mature and break apart, dispersing seeds that germinate soon thereafter. Seeds are eaten by mammals and birds, thus also dispersing seeds.

This tree once covered vast areas of subtropical forests in southern Brazil and neighboring portions of Argentina and Paraguay. Native Americans gathered cones to harvest the seeds for food. European settlers recognized Paraná pine as an important timber tree and it was logged extensively through the 20th century. Paraná pine now is one of the rarest trees in Brazil and is considered critically endangered due to a declining population caused by habitat loss and exploitation. In recognition of the past importance of Paraná pine, this tree is the symbol for the Brazilian State of Paraná.

The seeds, locally called pinhões, are still a prized food in Brazil. The seeds are similar to large pine nuts and are eaten after roasting or cooking in salt water.

Figure 3. The triangular shaped needles of Paraná pine are stiff and extremely sharp.

Other common English names for Paraná pine are Brazilian pine and candelabra tree. Common Portuguese names for Araucaria angustifolia are pinheiro-do-Paraná, pinheiro, araucária, pinho, pinho Brasileiro, pinheiro Brasileiro, pinheiro são josé, pinheiro macaco, pinheiro caiová, pinheiro das missões, curi, and curiúva. Common Spanish names are pino blanco and pino de Missiones.

Despite the common names, Paraná pine is not a pine (Pinus spp.) and instead is related to the Monkey-puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana;), Bunya-bunya tree (Araucaria bidwillii;), and the Norfolk Island pine (Araucaria heterophylla;), commonly encountered in southern Florida.

Paraná pine is sometimes confused with China fir (Cunninghamia lanceolata;), another large conifer commonly encountered in old landscapes along the Gulf Coast and north Florida. China fir differs in having pointed needles, bright green coloring, and a broader, irregular pyramidal form.

Paraná pine prefers well drained, slightly acidic soil in sun or light shade. It grows best in a mild, warm temperate climate typical of USDA Cold Hardiness Zones 7-9, and can tolerate occasional severe freezes. Paraná pine transplants well: a tree at Gardens of the Big Bend (Quincy, FL) was moved by tree-spade after four years. Subsequent growth continued at the same rate as before moving. Pests and diseases have not been reported.

Seeds must be obtained fresh and are viable for only about six weeks. Typically, freshly harvested seeds are ordered from Brazil and planted soon after being received. Seeds germinate easily within three months of sowing (Fig. 5).

Figure 4. Seeds of Paraná pine are about two inches long.

As a “living fossil”, Paraná pine is prized for its unusual appearance, horizontal branching and dark green color. This evergreen conifer grows too large for most residential situations. Paraná pine is best used as an accent or conversation piece in arboreta, botanic gardens, parks, campuses, golf courses and other large-scale landscapes.

Figure 5. Although perishable, fresh seeds will germinate within three months of sowing.

by Beth Bolles | Oct 28, 2014

A common question about insects when cold temperatures arrive is whether or not the cold will kill many pests. Although temperatures will occasionally drop below freezing in north Florida, it is normally not cold enough to significantly impact insect populations for the upcoming year.

Typical white grub of the genus Phyllophaga. Photograph by John L. Capinera, UF / IFAS

Even when we do receive a significant amount of cold weather, insects have many methods to survive weather changes. Some insects survive by moving to micro-habitats that are more resistant to temperature fluctuations. Beetle larvae may move deep in the soil or into logs and trees for protection. The grubs can continue feeding on decomposing material throughout winter months. Beneficial insects such as dragonflies and damselflies stay protected in their nymph forms in the mud of ponds and lakes.

One of the most famous insect survival strategies is migration. We are all familiar with the late summer and fall flights of the monarch butterfly to warmer regions of Mexico and southern California. Those butterflies and moths that do not migrate have their own survival techniques. They will overwinter in protective pupal cases to emerge as adults in the spring. Moth cocoons are spun of silk and may be composed of multiple layers, making them a good protection for the transforming insect.

Insects are adapted for survival and can live through far colder winters than we experience. Even though our cold weather will not drastically change insect populations, periods of cold will at least slow down their activity enough for us to enjoy a break from many pest worries.

by Roy Carter | Oct 28, 2014

Split citrus fruit. Image credit UF / IFAS

Citrus trees require a lot of care and attention to produce good quality fruit, yet even the most careful gardeners may run into the problem of split-fruit on their citrus trees. Split-fruit is a condition which strikes citrus trees in September and October and can wipe out a hundred or more fruit on a single tree. Researchers at the University of Florida have been studying fruit splitting for many years. Clear cut causes or solutions have not been found. My information on fruit splitting was provided by Extension Fruit Crop Specialist, Dr. Pete Andersen with IFAS located at Quincy, North Florida Research and Education Center.

Researchers have found that certain varieties of citrus tend to split more often than other. “Sweet Oranges” Tangelos” and certain varieties of Satsuma’s tend to split more than citrus which is not sweet. Grapefruit and acid fruits, such as lemons and limes rarely split.

The condition is known to be more common in seedlings and young trees than in older, more settled trees. However, split-fruit can be a very serious problem when it occurs on mature trees, because they usually have more fruit to lose.

Another condition which will cause fruit to split is insufficient copper in the soil. This used to be a much greater problem than it is today, due to the wide-spread use of copper in most fertilizer and spray programs. Potassium deficiency results in small, firm fruit with thin peels and increased fruit splitting. However, added potassium doesn’t correct splitting related to citrus varieties.

The most commonly held belief is that fruit splitting is caused by climatic conditions, since it only seems to occur at one time of the year. During the late summer and high humidity, followed by periods of drought. After a series of heavy rains, the trees absorb a great deal of moisture and force it into the fruit. Since the fruit is near maturity, the rind becomes less pliable and can’t expand rapidly enough to absorb the great volume of water from the trees. As a result the fruit splits.

Despite these findings, there are numerous cases of fruit splitting that doesn’t appear to be related to any of the above conditions. When the cause of the split is not fully understood, there is not absolute method of control. Also, there is no way to stop fruit splitting while it is occurring. The problem must be prevented before it starts. Attempts to control splitting through irrigation practices, fertilization and growth regulators have met with some success.

Fertilizer and irrigation practices won’t cure splitting, but may help to avoid large increase in the number of split fruit. In addition, growth regulators are available which can thicken the peel of the orange. Thicker peels have been found to split much less often that the thinner peels, due to their ability to withstand extra water pressure during the critical moths of the year.

If fruit splitting is a problem this year follow a recommended fertilizer program next year. This will insure a good supply of minor nutrients, especially copper. Make sure to keep the trees well watered during the dry periods of late summer and early fall. This will keep the fruit from swelling too rapidly, and splitting as a result.

by Judy Biss | Oct 21, 2014

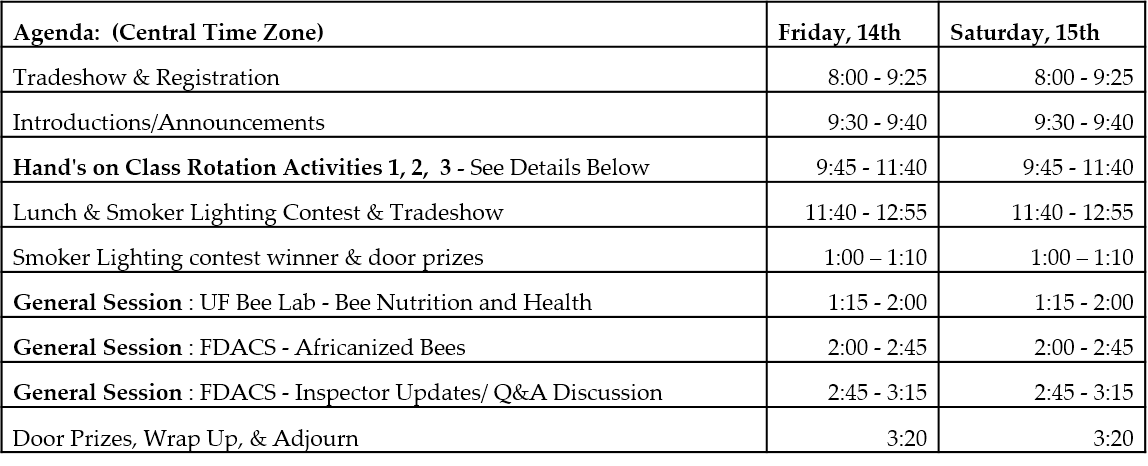

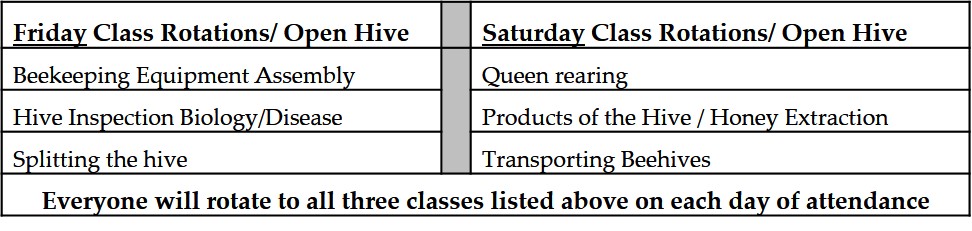

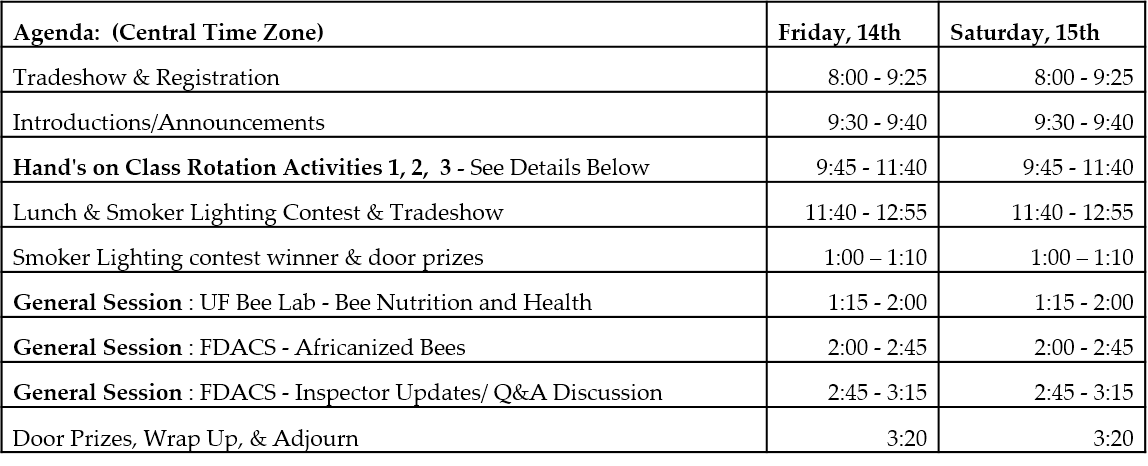

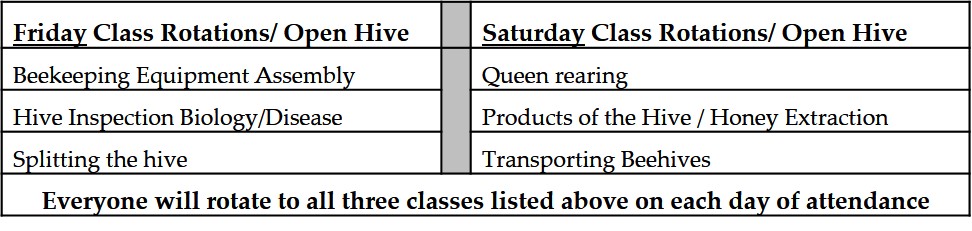

The Florida State Beekeepers, Central Panhandle, Chipola, and Tupelo Beekeepers Associations, in partnership with the Florida Department of Agriculture, and UF/IFAS Extension, are proud to offer the 4th annual Beekeepers Workshop & Trade-show November 14th & 15th! This event will provide hands-on educational opportunities including interaction with expert beekeepers, open hive demonstrations, and more! This event will be held at the UF/IFAS Extension Washington County Office, 1424 Jackson Avenue, Chipley, FL 32428, 850-638-6180

Registration: Includes Lunch & Refreshments

Registration: Includes Lunch & Refreshments

$25 for one day or $40 for both days per person.

$10 age 12 and under each day.

Late fee of $10.00 after November 5th.

Please download this registration form to attend:

Here is a printable event flyer with details: