by Beth Bolles | Mar 30, 2017

We often talk about sandy, nutrient poor soil in Florida and how difficult it is for growing many favorite landscape plants. Gardeners may spend considerable time and money amending soils with organic matter to improve quality.

The low maintenance approach is to embrace your sandy soil and consider plants that thrive in sandy, well-drained soil. One very attractive native shrub that actually prefers this type of soil is false rosemary, Conrandina canescens.

False rosemary is a member of the mint family that is well adapted to drier, sandy soils. It can be found in many coastal communities growing in natural areas. It is easily recognized in the spring and early summer by light purple blooms. Considered a small shrub or groundcover, False rosemary needs full sun. One plant can easily spread out to 4-5 feet in diameter with a height of 2-3 feet.

False rosemary is an attractive native plant for Gulf Coast landscapes. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF Escambia County Extension

False rosemary does have aromatic foliage and is attractive to bees. It is a very low maintenance plant once established and its few issues tend to be related to soils with too much moisture and plants being shaded after establishment. New seedlings will emerge around the main plant when growing conditions are right. If you want to try this native plant in your landscape, talk to a local nursery.

False rosemary flowers are attractive to pollinators. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF Escambia County Extension

by Mark Tancig | Mar 29, 2017

As an extension agent, I’m always curious of what plants folks are using in the landscape. One plant I’ve been noticing more and more of in north Florida, both in containers and in landscape beds, is asparagus fern. Three different plant species go by the name asparagus fern – Sprenger’s fern (Asparagus aethiopicus), foxtail fern (Apsaragus densiflorus), and lace fern (Asparagus setaceus). Property owners should refrain from selecting these plants since they are another example of invasive, exotic species that can spread to natural areas and effect native plant communities.

Native to South Africa, Asparagus species are technically not a fern, but related to lilies, and, yes, asparagus. Its ease of growth has made them a go-to choice for gardeners looking for a hardy, attractive plant. Unfortunately, the red berries that follow the small, white, scented flowers are fed on and spread by birds. The seeds germinate easily and can become established in other parts of the garden or, even worse, a local natural area. The ability of Sprenger’s fern to spread into and disrupt natural ecosystems has earned it a spot on the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s List of Invasive Species as a Category I invasive plant. Category I plants are reserved for those plants that have been documented as causing ecological harm to Florida’s ecosystems. Foxtail fern and lace fern should also be used with caution.

Asparagus fern in a storefront planter. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

Birds can carry the red berries near and far. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

To remove asparagus fern from the landscape, manual or mechanical removal can be effective for small areas. Be careful to dig up all roots. For larger areas, the use of a dilute glyphosate herbicide product will provide control. Retreatment may be necessary.

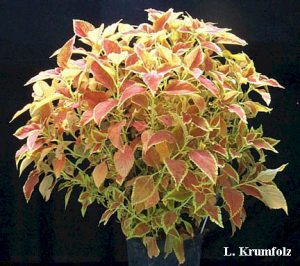

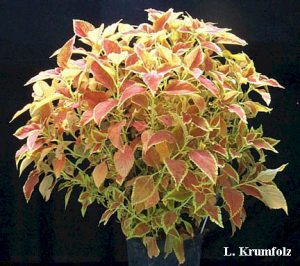

If you’re looking for other alternatives to asparagus fern, try these Florida-Friendly alternatives: Coastal sunflower (Helianthus debilis), coontie (Zamia pumila), Coleus (Plectranthus scutellarioides), or Cast Iron plant (Aspidistra elatior).

Coastal sunflower. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Coontie. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Coleus. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Cast iron plant. Photo Credit: Julie McConnell.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Mar 29, 2017

Everyone, or at least everyone fortunate enough to grow up in the South, has a fond memory tucked away of a sight or smell of a plant that reminds them of the good old days. Maybe it’s the ancient camellia at your grandmother’s house that just feels like home when you see it. Maybe it’s a persimmon tree with fruit weighing on the branches, the smell of baked persimmon bread cooling in the kitchen close behind. For me and countless others, it’s the sight of the iconic native flowering dogwood (Cornus florida) blooming each spring in the understory of Panhandle forests. However, if you’ve been paying attention, the spring dogwood bloom has diminished with each passing year, leaving many folks wondering what happened. As with many things, the answer is multi-faceted and complicated.

First, as homeowners who have grown dogwoods for many years are well aware, dogwoods are notoriously susceptible to harsh site conditions. In the landscape setting, much of the difficulty in growing dogwoods may be attributed to Florida’s frequent extended droughty periods and improperly citing the trees in a full-sun location. dogwoods naturally prefer a cool, moist root zone and protection from the hot afternoon sun; failure to provide such a setting will most likely lead to scorched-appearing foliage, overall poor performance and a short-lived tree.

Various Dogwood Leaf Spots

More problematic are the many diseases dogwoods are prone to, including several fungal leaf spots, cankers and mildew diseases, all of which impair their ability to create energy and store the needed nutrients to survive tough periods (frequent droughts). All of these diseases are much more problematic in the unseasonably warm, wet winters and cool, wet springs Floridians have been experiencing with regularity over the last decade. It is good practice to actively clean up any fallen, diseased leaves as well as to prune out any obviously dead or diseased wood to prevent problems from spreading further, but total suppression of these diseases is impractical for most homeowners.

As if all of those problems weren’t enough, the most sobering issue currently facing flowering dogwood is a fungal disease known as dogwood anthracnose (Discula destructiva). D. destructiva has been confirmed responsible for the decline of dogwoods in more upland areas around the foothills of the Appalachians and has been surmised to have moved south into the coastal plain, although its presence in our area has largely been undocumented. As with other pathogens, disease incidence is increased in already stressed trees as well as in mild, wet-weather conditions in the spring and fall. Symptoms of D. destructiva usually begin with purplish spots on the margins of leaves in early summer, with infected leaves hanging onto the tree through winter. The disease then spreads down through the tree and manifests itself as a sort of dieback of twigs and limbs, eventually forming cankers and killing the tree.

As dire as the dogwood situation may seem, there are some potential solutions. First, if you must plant a flowering dogwood, make sure you give it an ideal situation. Irrigate when rainfall is inconsistent, apply a layer of an organic mulch (pinestraw, wood chips, etc.) at a depth of 2”-3”, and plant in a protected, shady situation. If growing a native dogwood might seem too challenging, there is a related species from Asia called kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa) that deserves to be planted more. Kousa dogwood is not a perfect tree but it retains most everything we love about native dogwoods without the disease issues!

Young ‘Empress of China’ in the author’s lawn.

Kousa’s retain the classic creamy white flowers, attractive berries in fall, and layered branching (called sympodial branching) of our native dogwoods but also bring a few extra attributes to the table. Kousa dogwood grows to a rounded 15’-20 in height and width, is much more tolerant of cultural extremes than flowering dogwood and is resistant to the various diseases that plague native dogwoods. Also, there is a subspecies of kousa dogwood, Cornus kousa var. angustata that is even evergreen in our area, no more barren limbs in the winter! The most popular selection of this subspecies is a beautiful little tree being marketed as ‘Empress of China’ through the southern living plant collection; I am currently trialing this tree in my yard and it has impressed so far.

So to wrap up, if the decline of the dogwoods has you down, there are three things you can do:

- Give your existing dogwoods some TLC, keep them well-watered in droughty periods and mulch to keep the roots cool.

- Cut out any dead or diseased branches in existing dogwoods and rake and dispose of leaves from previous years that are lying around.

- If you want to plant a new dogwood, try a kousa dogwood (Cornus kousa) as this species is a more than adequate replacement for Cornus florida!

As always, consult your local UF/IFAS Extension Office with any questions or concerns you have regarding your landscape and happy gardening!

by Mary Salinas | Mar 20, 2017

About the Spring Festival of Flowers

The University of Florida, IFAS and the Pensacola State College Milton Campus invites you to join them for one of the largest festivals of the season. This is a popular event that draws plant enthusiast from near and far. This festival features plant nurseries, UF student club plant sale, arts & crafts, great food, music and educational opportunities.

Location

University of Florida, IFAS and the Pensacola State College Milton Campus located at 5988 Highway 90, Milton.

Dates and Times

Friday, April 7, 2017 * 9 AM – 5 PM

Saturday, April 8, 2017 * 9 AM – 4 PM

Sunday, April 9, 2017 *9 AM – 4 PM

by Matt Lollar | Mar 20, 2017

A type III fairy ring. Photo Credit: Alex Bolques, Assistant Professor, Florida A&M University

Mushrooms often are grouped in a circle in your lawn. This is due to the circular release of spores from a central mushroom. “Fairy Ring” is a term used to describe this phenomenon. Fairy rings can be caused by multiple mushroom species such as Chlorophyllum spp., Marasmius spp., Lepiota spp., Lycoperdon spp., and other basidiomycete fungi.

Occurrence

Fairy rings most commonly invade your yard during the summer months, when the Florida panhandle receives the most rain. The mushrooms cause the development and spread of the rings by the release of spores. Spores produce more mushrooms and are similar to the seed produced by plants.

Fairy Ring “Types”

Fairy rings can be seen in three forms:

- Type I rings have a zone of dead grass just inside a zone of dark green grass. Weeds often invade the dead zone.

- Type II rings have only a band of dark green turf, with or without mushrooms present in the band.

- Type III rings do not exhibit a dead zone or a dark green zone, but a ring of mushrooms is present.

The size and fill of rings varies considerably. Rings are often 6 ft or more in diameter. The fill of a ring can range from a quarter circle to a semicircle or full circle.

Cultural Controls

The rings will disappear naturally, but it could take up to five years. Although it is possible to dig up the fairy ring sites, it is a good possibility the rings will return if the food source (buried, rotting wood or other organic matter) for the fungi is still present underground.

In some situations, the fungi coat the soil particles and make the soil hydrophobic (meaning it repels water), which will result in rings of dead grass. If the soil under this dead grass is dry but the soil under healthy grass next to it is wet, then it is necessary to aerate or break up the soil under the dead grass with a pitchfork or other cultivation tool.

Rings of dead turf due to fairy ring fungi. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension.

Chemical Controls

Effective fungicides include products containing the active ingredients azoxystrobin, flutolanil, metconazole, pyraclostrobin, and triticonazole.

Fungicides inhibit the fungus only. They do not eliminate the dark green or dead rings of turfgrass and do not solve the dry soil problem.

A homeowner’s guide to lawn fungicides can be found at the University of Florida/IFAS Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) website (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/document_pp154).