by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2025

Many who have snorkeled or dove in the Florida Keys have most likely encountered nurse sharks there – they are quite common. But here in the northern Gulf – though present – encounters are not as frequent. In the Keys you can don a mask, swim along a seawall, bridge piling, or over limestone bottom in shallow water and found one – maybe several. In the northern Gulf encounters are more offshore by SCUBA alone, and I would say – still not that common.

All this to say that one was seen off a dock recently in Escambia County inside the bay. It was swimming along the edge of the dock in a seagrass bed searching for something to eat. Again, this would not be abnormal if in south Florida, but a cool event in our area.

Nurse sharks are docile fish recognized by their brownish copper coloration, two large dorsal fins set back on their dorsal side, and barbels extending from their upper jaw similar to catfish. These barbels indicate they are more bottom feeders, and they spend a lot of time lying on the bottom. Though they can reach lengths of 14 feet, nurse sharks are not considered a threat – unless you mess with them – and exciting to see.

They are considered a tropical species – hence the lower number of encounters in our area. They prefer hardbottom – such as coral reefs and limestone shelves – higher salinities, dissolved oxygen levels, and clear water. Over this summer local water temperatures have increased, and the lack of rain has increased salinities across the area. The lower amount of rain has reduced stormwater runoff from land and allowed the water to become clearer. Everything that a nurse shark would want.

As mentioned, encounters with this species are not considered threatening and a very cool memory. We do not know how long the current conditions will last but maybe you too will see one. It would be pretty exciting.

Nurse shark inside bay in Escambia County.

Photo: Angela Guttman

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 22, 2025

Introduction

The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is the only resident turtle within brackish water and estuarine systems in the United States (Fig. 1). They prefer coastal estuarine wetlands – living in salt marshes, mangroves, and seagrass communities. The literature suggests they have strong site fidelity – meaning they do not move far from where they live. Within their habitat they feed on shellfish, mollusk and crustaceans mostly. In early spring they will breed. Gravid females will venture along the shores of the bay seeking a high-dry sandy beach where they will lay a clutch of about 10 eggs. She will typically return to lay more than one clutch each season. Nesting will continue through the summer. Hatching begins mid-summer and will extend into the fall. Hatchings that occur in late fall may overwinter within the nest and emerge the following spring. They live 20-25 years.

Fig. 1. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

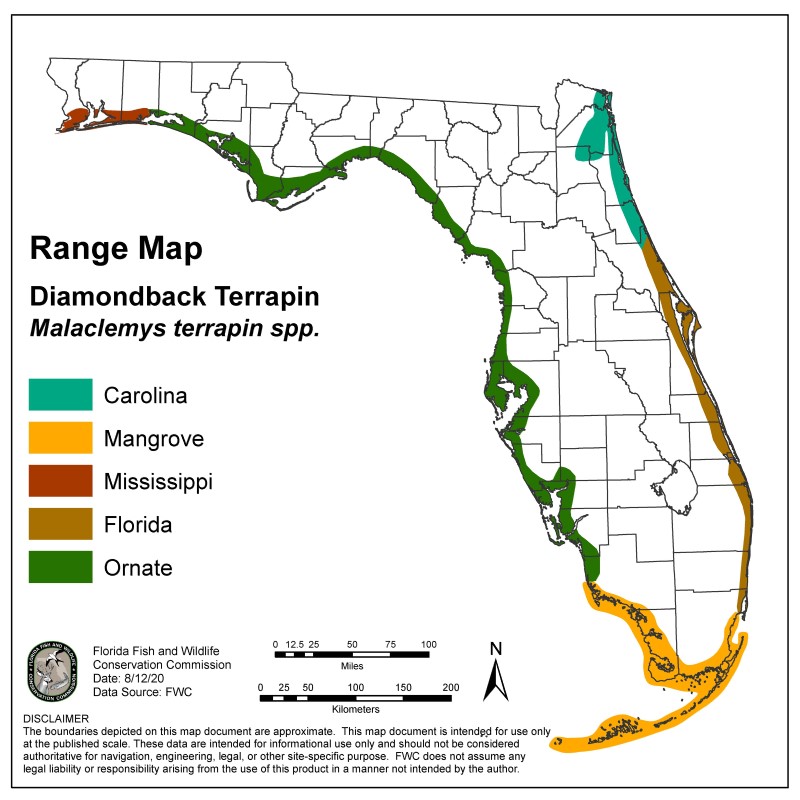

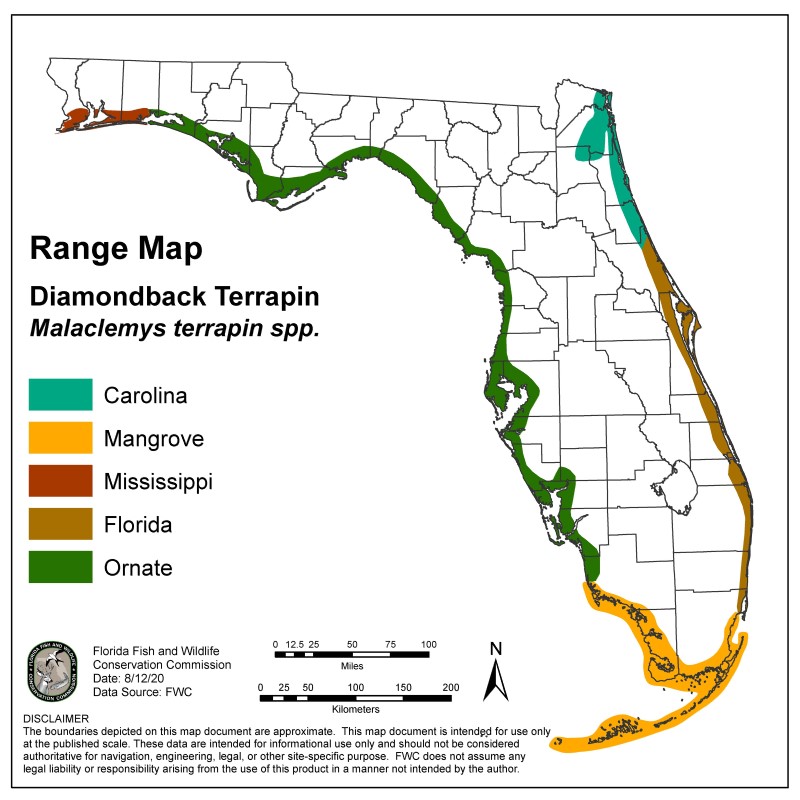

Terrapins range from Massachusetts to Texas and within this range there are currently seven subspecies recognized – five of these live in Florida, and three are only found in Florida (Fig. 2). However, prior to 2005 their existence in the Florida panhandle was undocumented. The Panhandle Terrapin Project (PTP) was initially created to determine if terrapins did exist here.

Fig. 2. Terrapins of Florida.

Image provided by FWC

The Scope of the Project

Phase 1

The project began in 2005 using trained volunteers to survey suitable habitat for presence/absence. Presence is determined by locating potential nesting beaches and searching for evidence of nesting. Nesting begins in April and ends in September – with peak nesting occurring in this area during May and June. The volunteers are trained in March and survey potential beaches from April through July. They search for tracks of nesting females, eggshells of nests that were depredated by predators, and live terrapins – either on the beach or the heads in the water. Often volunteers will conduct 30-minute head counts to determine relative abundance. Between 2005 and 2010 the team was able to verify at least one record in each of the panhandle counties.

Phase 2

The next phase is to determine their status – how many nesting beaches does each county have, and how many terrapins are using them? A suitability map was developed by Dr. Barry Bitters as a Florida Master Naturalist project to locate suitable nesting beaches. Volunteers would visit these during the spring to determine whether nesting was occurring, and the relative abundance was determined using what we called the “Mann Method” – developed by Tom Mann of the Mississippi Department of Wildlife, along with the 30-minute head counts. The Mann Method involved counting the number of tracks and depredated nests within a 16-day window. The assumption to this method was that nesting females would lay multiple clutches each season – but they did not lay more than one every 16 days. Going on another assumption, that the sex ratio within the population was 1:1, each track and depredated nest within a 16-day window was a different female and doubling this number would give the relative abundance of adults in this population. Between 2007 and 2023 we were able to determine the number of nesting beaches in each county and relative abundance in three of those counties (see results below).

Phase 3

Partnering with the U.S. Geological Survey, we were able to move to Phase 3 – which involves trapping and tagging terrapins. Doing this gives the team a better idea of where the terrapins are going and how they are using the habitat. To trap the terrapins, we use modified crab traps (modified so that the terrapins had access to air to breath), seine nets, fyke nets, dip nets, and by hand – the most effective has been modified crab traps (Fig. 3). These traps are placed in terrapin habitat over a 3-day period, being checked daily. Any captured terrapins are measured, weighed, sexed, marked using the notch method, and given a Passive Intergraded Transponder (PIT) tag. Some of the terrapins are given a satellite tag where movement could be tracked by GPS (Fig. 4). We are now bringing on acoustic tagging for some counties. This involves placing acoustic receivers on the bottom of the bay which will detect any terrapin (with an acoustic tag) that swims nearby. Results are below.

Fig. 3. Modified crab traps is one method used to capture adults.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Fig. 4. This tag with an antenna can be detected by a satellite and tracked real time.

Photo: USGS

Phase 4

This phase involves collecting tissue samples for genetic analysis. Currently it is believed that the Ornate terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin macrospilota) ranges from Key West to Choctawhatchee Bay, and the Mississippi terrapin (M.t. pileata) ranges from Choctawhatchee Bay to the Louisiana/Texas border. The two subspecies look morphologically different (Fig. 5) and the team believes terrapins resembling the ornate terrapin have been found in Pensacola Bay. Researchers in Alabama have also reported terrapins they believe to be ornate terrapins in their waters as well. The project is now working with a graduate student from the University of West Florida who is genetically analyzing tissue samples from trapped terrapins to determine which subspecies they are and what the correct range of these subspecies. This phase began in 2025, and we do not have any results at this time.

Fig. 5. The Mississippi terrapin found in Pensacola Bay is darker in color than the Ornate terrapin found in other bays of the panhandle.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Ornate Diamondback Terrapins Depend on Coastal Marshes and Sea Grass Habitats

Photo: Erik Lovestrand.

2025 UPDATE AND RESULTS

In 2025 we trained 188 volunteers across each county – including state park rangers and members of the Florida Oyster Corps. 47 (25%) participated in at least one survey.

We logged 345 nesting surveys and 17 trap days.

No seining or fyke nets were conducted in 2025.

Phase 1 – Presence/Absence Update

| County |

Presence |

Notes |

| Baldwin |

Yes |

A single deceased terrapin was found in western Baldwin County |

| Escambia |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Santa Rosa |

Yes |

Two new locations were identified this year |

| Okaloosa |

Yes |

Encounters were lower this year |

| Walton |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN WALTON COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Bay |

Yes |

FIRST EVIDENCE OF NESTING IN BAY COUNTY VERIFIED THIS YEAR |

| Gulf |

Yes |

Team encountered nesting again this year |

| Franklin |

ND |

ND |

Phase 2 Nesting Survey – Update

| County |

# of primary beaches1 |

# of secondary beaches2 |

# of surveys |

# of encounters |

FOE3 |

| Baldwin |

0 |

TBD |

14 |

04 |

.00 |

| Escambia |

2 |

35 |

99 |

7 |

.07 |

| Santa Rosa |

3 |

45 |

137 |

25 |

.18 |

| Okaloosa |

4 |

3 |

20 |

1 |

.05 |

| Walton |

1 |

4 |

28 |

2 |

.07 |

| Bay |

3 |

3 |

47 |

14 |

.30 |

| TOTAL |

13 |

17 |

345 |

49 |

.14 |

1 primary beaches are defined as those where nesting is known to occur.

2 secondary beaches are defined as those where potential nesting is high but has not been confirmed.

3 FOE (Frequency of Encounters) is the number of terrapin encounters / the number of surveys conducted.

4 There was one deceased terrapin found by a tour guide in Baldwin County but was not part of the project.

5 There are potential nesting sites on Pensacola Beach that are technically in Escambia County but covered by the Santa Rosa team. The Escambia team focused on the Perdido Key area.

Phase 3 Trapping/Tagging Update

We currently have 8 years of data.

Terrapins have been tagged in 7 of the 8 panhandle counties.

1483 captures, 1061 individuals.

2025 Capture Effort

| Method |

County |

Number |

Description |

Condition |

| Hand capture |

Escambia |

1 |

1 adult male |

Deceased |

| Hand capture |

Santa Rosa |

5 |

4 adult females

1 unknown |

Released, deceased |

| Hand capture |

Okaloosa |

1 |

1 adult female |

Released |

| Dip Net |

Santa Rosa |

1 |

1 adult male |

Released |

| Crab Traps |

Santa Rosa |

34 |

4 juvenile females

5 adult females

25 adult males |

Released |

|

Okaloosa |

4 |

1 juvenile female

3 adult males |

Released |

| TOTAL |

|

46 |

5 juvenile females

10 adult females

30 adult males

1 unknown |

|

Preliminary information subject to revision. Not for citation or distribution.

Satellite Tagging Information

Due to the size of the tags – only large females are satellite tagged at this time.

Big Momma – tracked for 188 days – averaged 0.16 miles.

Big Bertha – tracked for 137 days – averaged 35.83 miles.

2025 Tracking Effort

| County |

Tagging Effort |

| Santa Rosa |

2 satellite tagged

6 acoustically tagged |

| Okaloosa |

1 satellite tagged |

| TOTAL |

8 tagged for tracking |

Phase 4 Update

This phase began in 2025 and there are no results at this time.

Summary

2025

17 trainings were given in 7 of the 8 counties of the Florida panhandle (including Baldwin County AL).

188 were trained; 47 (25%) conducted at least one survey.

345 surveys were logged; terrapins (or terrapin sign) were encountered 49 (14%) of those surveys.

Every county had at least one encounter during a nesting survey.

17 trapping days were conducted; 46 terrapins were captured; 37 (83%) were captured in modified crab traps; 7 were captured by hand; 1 was captured in a dip net.

8 terrapins were tagged for tracking; 6 acoustically; 2 with satellite tags.

Since 2007

511 have been trained.

1449 surveys have been logged; 347 encounters have occurred; Frequency of Encounters is 24% of the surveys.

Discussion

Phase 1

We have shown that diamondback terrapins do exist in the Florida panhandle and in Baldwin County AL.

Phase 2

We currently have 13 primary nesting beaches we are surveying weekly during nesting season across the panhandle. There were 17 secondary nesting beaches surveyed and most likely there are many more to visit. Nesting seems to be more common in late spring, but the Frequency of Encounters has been declining since 2023. This could be due to less terrapin activity but could also be due to evidence being difficult to find. We will continue to monitor to see how this trend continues.

Phase 3

The team has captured 1483 terrapins, the majority of which were from the eastern panhandle. Satellite tagged females suggest more than one has traveled over 30 miles from where they were tagged. This goes against the idea that terrapins have strong site fidelity. However, all the terrapins tagged were large females (due to size of the tags) so we are looking at the movements of only the larger females – not the population as a whole. The movements of these females also suggest they may use seagrass beds as much as the salt marshes.

Training for volunteers occurs in March of each year. If you are interested in participating, contact Rick O’Connor – roc1@ufl.edu.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 15, 2025

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

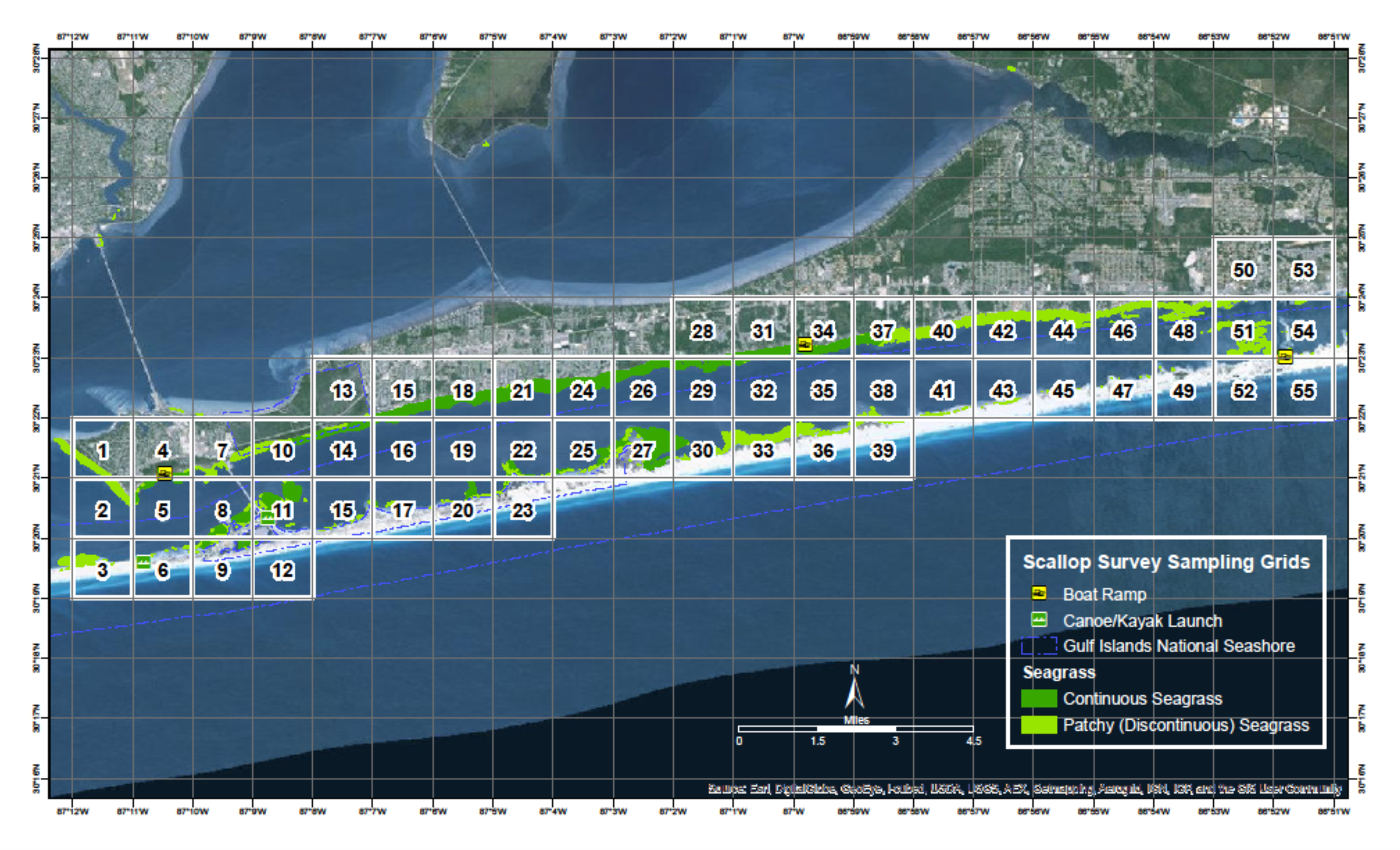

Scallop harvest area.

Image: Florida Department of Environmental Protection

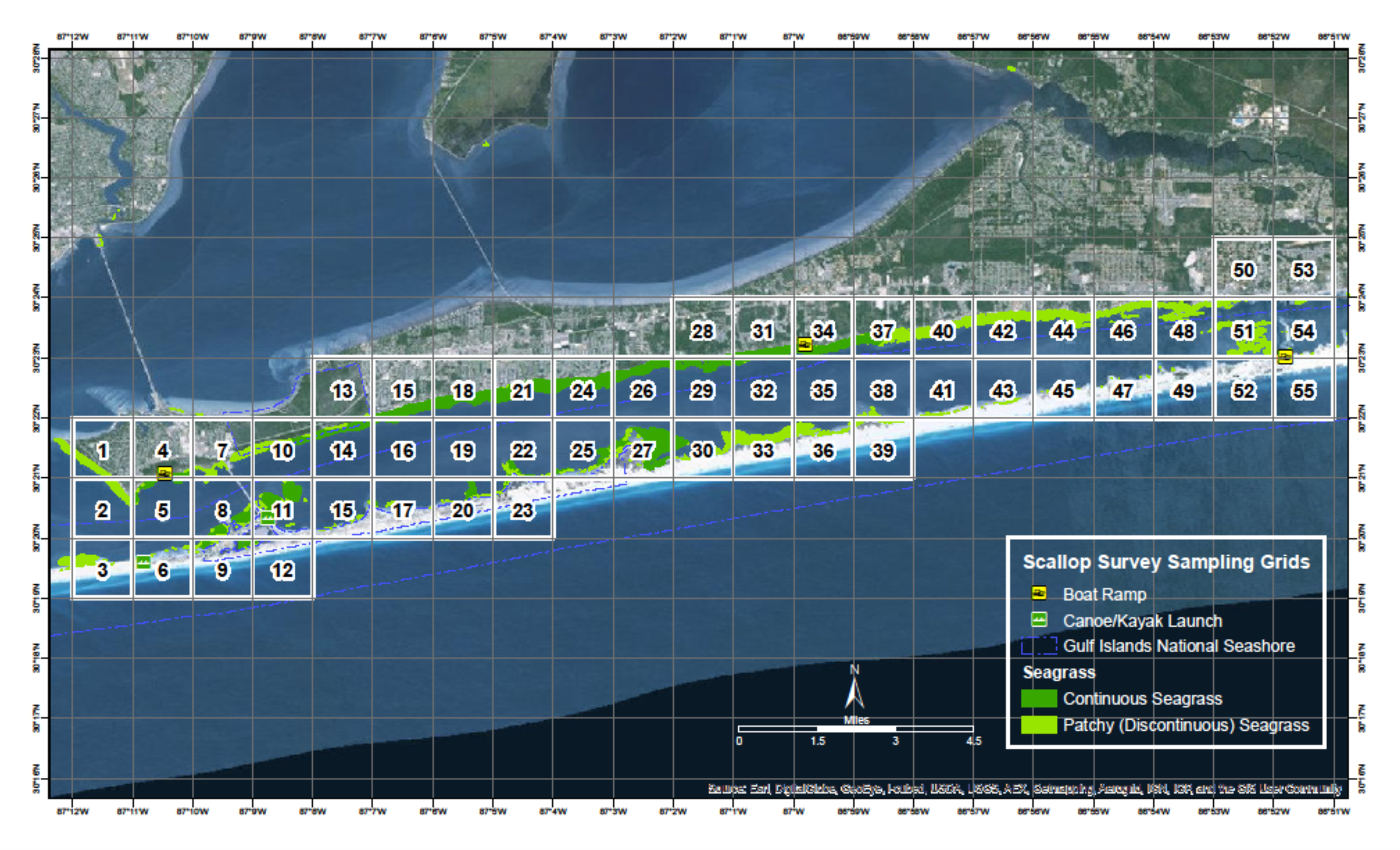

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2025 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

Snorkel transect method.

Image: University of Florida.

2025 Results

138 volunteers on 32 teams surveyed 22 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (36%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 162 transects (16,200m2) were surveyed logging 8 scallops. All live scallops were reported from Santa Rosa Sound this year.

2025 Big Lagoon Results

13 teams surveyed 9 of the 11 grids (81%) within Big Lagoon. 76 transects were conducted covering 7,600m2.

No scallops were logged in 2025 though scallop shells were found. No sea urchins were reported but scallop predators – such as conchs, blue crabs, and rays were. This equates to 0.00 scallops/200m2 and moves Big Lagoon from a vulnerable system last year to a collapsed one this year. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in 5 of the 9 grids (56%) and was reported abundant in grid 2.

2025 Santa Rosa Sound Results

19 teams surveyed 13 of the 55 grids (23%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 86 transects were conducted, covering 8,600m2.

8 scallops were logged which equates to 0.19 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and rays. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in 7 of the 13 grids (54%) and was reported as abundant in 4 of those.

2015 – 2025 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| 2025 |

76 |

0 |

0.00 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

399 |

104 |

0.52 |

2015 – 2025 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| 2025 |

86 |

8 |

0.19 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

2591 |

44 |

0.34 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. Big Lagoon reached the vulnerable level in 2024, but no scallops were found there in 2025, returning to a collapsed state.

There are some possible explanations for low numbers in 2025.

- It has been reported by some shellfish biologists that bay scallops have a “boom-bust” cycle. Meaning that one year their populations “boom” before returning to normal numbers. We could have witnessed this between 2024 and 2025.

- Though we did not monitor water temperatures, July 2025 was extremely hot, and many volunteers reported their sites felt like “bath water”. Collecting efforts on other projects during July reported not capturing anything – no pinfish, hermit crabs – their nets were empty. It is possible that these warm conditions could have caused many organisms to move to deeper/cooler depths. Note here; as the project moved into August temperatures did begin to cool and searchers began reporting fish, conchs, blue crabs, and rays.

The Pensacola Bay area continues to have a collapsed system. The larger populations found in 2024 suggest that there are scallops in the area but may not be enough to increase their population status from collapsed to vulnerable. We will continue to monitor each July.

It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 138 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Ethan Sadowski John Imhof Kaden Luttermoser

John Wooten Susan Pinard Matt MacGregor

Christian Wagley Sean Hickey Jason Buck

Brian Mitchell Angela Guttman Caitlen Murrell

Samantha Brady (USM) Michelle Noa Kira Benton

Monica Hines Wesley Allen Kelly Krueger

Mikala Drees Jonathan Borowski Michael Currey

Gina Hertz Melinda Thoms Beau Vignes

Bill Garner Robert Moreland Stephanie Kissoon

Nick Roest Leah Yelverton

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found.

Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

by Laura Tiu | Aug 17, 2025

A blue bowl filled with bay scallop linguini in a white wine garlic sauce.

I love harvesting and eating local Bay scallops. Port St. Joe Bay is the scalloping area closest to Walton County. These tasty mollusks live in sea grass beds in shallow water. This makes them easy to find simply snorkeling, on a paddle board, kayak or from a boat.

Scallops used to be plentiful in all our Bays, including the Choctawhatchee Bay. These shellfish, however, are sensitive to environmental changes and due to their relatively short lifespan, are susceptible to periodic collapses. To enjoy recreational scalloping for years to come, it is important that safety and conservation stay top of mind. Following the best practices below will ensure the bay scallop fishery is protected for future generations to enjoy.

- Throw back small scallops. Recreational harvest occurs before scallops are given the chance to reproduce. Smaller ones are younger than older and have a higher chance of living to reproduce in the fall and possibly again in the winter. In Florida, scallops typically live for about 18 months. While it is not legally required, throwing back small scallops (those less than 2 inches) is a great way to do your part to protect the fishery. Also, small scallops have smaller muscle meat so it might not even be worth your while to shuck the small ones.

- Keep only what you will eat. While “limiting out” might seem like an obvious goal, don’t forget that someone will have to shuck all those scallops! One pint of scallop meat (the typical daily limit for one person) is roughly four servings of scallops. Rather than setting a goal of catching your limit, consider setting a more conservative goal based on how much meat you will eat. Scallop meat only keeps in the fridge for 1 day or about 3 months frozen. Plan accordingly!

- Never double dip. Locals and law enforcement officers in the bay scallop harvest areas often report “double dipping”, or scallopers going out for a second trip after landing one limit. Without question, this is illegal. But is is also highly unethical and shows disrespect for the fishery and the people with livelihoods that depend on bay scallops.

- Protect seagrass when boating. Be aware of seagrasses while boating in shallow areas! Many species, including bay scallops, depend on seagrasses. Damage from propellers and boat anchors (called seagrass scarring) reduces habitat quality and resilience of seagrasses over the long-term. Please visit the Be Seagrass Safe website for more information

- Discard shells responsibly. Shells and soft tissues should be disposed of in open Gulf of Mexico waters with moderate to strong currents that are not channels, canals, marinas, springs, or boat ramps. Shells and soft tissues can cause problems for water quality and boating when dumped in high traffic areas close to shore. Shells disposed of in shallow swimming areas, such as springs or sandbars, pose a serious hazard to swimmers. If you clean your catch on shore, dispose of shells/soft tissues in the trash or clean and re-use for crafts or landscaping around the house.

Scalloping

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 7, 2025

This tree was downed during Hurricane Michael, which made a late-season (October) landfall as a Category 5 hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

There are plenty of jokes about the four seasons in Florida—in place of spring, summer, fall, and winter; we have tourist, mosquito, hurricane, and football seasons. The weather and change in seasons are definitely different in a mostly-subtropical state, although we in north Florida do get our share of cold weather (remember that snow this year?!).

A disaster supply kit contains everything your family might need to survive without power and water for several days. Photo credit: Weather Underground

All jokes aside, hurricane season is a real issue in our state. With the official season having recently begun (June 1) and running through November 30, hurricanes in the Gulf-Atlantic region are a legitimate concern for fully half the calendar year. According to records kept since the 1850’s, Florida has been hit with more than 120 hurricanes, double that of the closest high-frequency target, Texas. Hurricanes can affect areas more than 50 miles inland, meaning there is essentially no place to hide in our long, skinny, peninsular state.

Flooding and storm surge are the most dangerous aspects of a hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I point all these things out not to cause anxiety, but to remind readers (and especially new Florida residents) that is it imperative to be prepared for hurricane season. Just like picking up pens, notebooks, and new clothes at the start of the school year, it’s important to prepare for hurricane season by firing up (or purchasing) a generator, creating a disaster kit, and making an evacuation plan. We even have disaster preparedness sales tax exempt holidays in Florida; one in early June and another in the heart of the season, August 24-September 6.

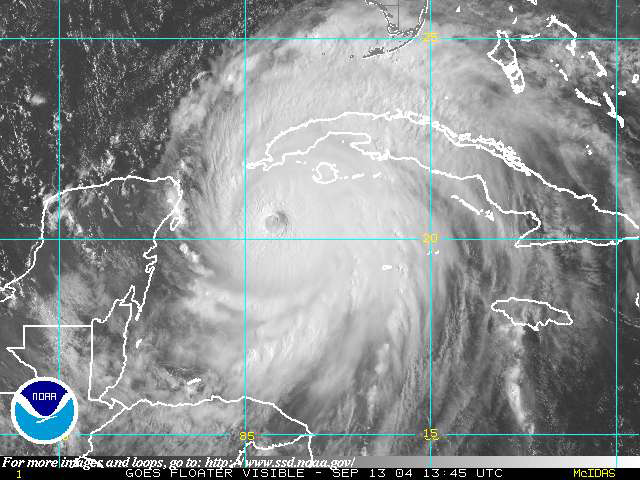

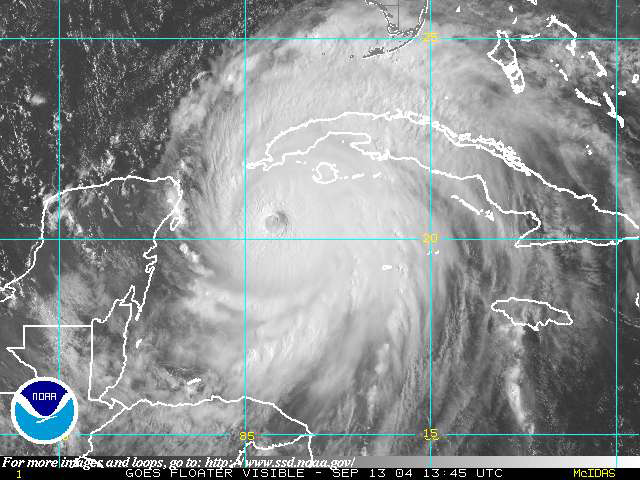

Peak season for hurricanes is September. Particularly for those in the far western Panhandle, September 16 seems to be our target—Hurricane Ivan hit us on that date in 2004, and Sally made landfall exactly 16 years later, in 2020. But if the season starts in June, why is September so intense? By late August, the Gulf and Atlantic waters have been absorbing summer temperatures for 3 months. The water is as warm as it will be all year–in 2023 even reaching over 100 degrees Fahrenheit–as ambient air temperatures hit their peak. This warm water is hurricane fuel—it is a source of heat energy that generates power for the storm. Tropical storms will form early and late in the season, but the highest frequency (and often the strongest ones) are mid-August through late September.

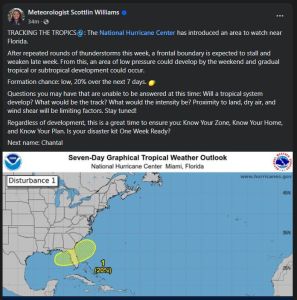

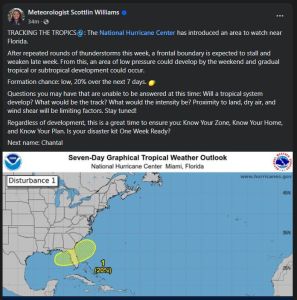

Pay attention to local meteorologists on social media, news, and radio. This alert was posted just yesterday online by the Escambia County Emergency Management Coordinator.

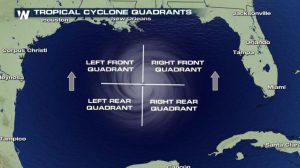

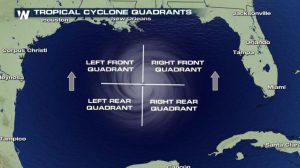

If you have lived in a hurricane-prone area, you know you don’t want to be on the front right side of the storm. For example, here in Pensacola, if a storm lands in western Mobile or Gulf Shores, Alabama, the impact will nail us. Meteorologists divide hurricanes up into quadrants around the center eye. Because hurricanes spin counterclockwise but move forward, the right front quadrant will take the biggest hit from the storm. A community 20 miles away but on the opposite side of a hurricane may experience little to no damage.

The front right quadrant of a hurricane is the strongest portion of a storm. Photo credit: Weather Nation

Hurricanes bring with them high winds, heavy rains, and storm surge. Of all those concerns, storm surge is the deadliest, accounting for about half the deaths associated with hurricanes in the past 50 years. Many waterfront residents are taken by surprise at the rapid increase in water level due to surge and wait until too late to evacuate. Storm surge is caused by the pressure of the incoming hurricane building up and pushing the surrounding water inland. Storm surge for Hurricane Katrina was 30 feet above normal sea level, causing devastating floods throughout coastal Louisiana and Mississippi. Due to the dangerous nature of storm surge, NOAA and the National Weather Service have begun announcing storm surge warnings along with hurricane and tornado warnings.

For helpful information on tropical storms and protecting your family and home, look online here for the updated Homeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for Natural Disasters, or reach out to your local Extension office for a hard copy.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2025

Snails and slugs belong to one of the largest phyla of animals on the planet – the mollusks. Mollusks are known for their calcium carbonate shells and seashell collecting along the shoreline has been a popular hobby for centuries. There are an estimated 50,000 to 200,000 species of mollusk worldwide. One group – the gastropods – have an estimated 40,000 to 100,000 species alone. This is the group that includes the snails and slugs.

Snails are soft-bodied creatures who produce a single, usually coiled, shell in which they live. The coiled shell has an opening called the aperture through which they can extend some, or most of their body. The elongated soft body “slugs” across the sea bottom searching for food which could be vegetation for some – like the small nerite snails found in our bays, or animals – like the venomous cone snails, or detritivores – like the periwinkle snails.

The Olive Nerite.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Many species of local snails produce egg cases in which they deposit their developing eggs. These are often found while people are beach combing. The most frequently encountered locally are the tube-shaped clusters of the oyster drill, the coin shaped chain of the lightning whelk, and the one that – to me – resembles the top of a vase or jar belonging to the moon snail.

The egg case of the Lightning Whelk.

Photo: Project Noah

The variety of snails found in the northern Gulf is immense – so, we will cover only a few of the more common.

Walking along the Gulf side, gazing down at the shells of snails washed ashore, one often finds the small ceriths. These tiny, elongated shells are small and look like a canine tooth. These are herbivores and detritivores.

Cerith

Photo: iNaturalist

The Florida Fighting Conch is often found – but not always in whole condition. This is a true conch and herbivorous.

Florida Fighting Conch

Photo: iNaturalist

One not as common while beachcombing, but more common while snorkeling is the olive snail. These are fast burrowing snails that feed on bivalves and carrion they may find. I often find trails crisscrossing the sandy bottom made by these snails just off the beach.

Olive snail

Photo: Flickr

Over on the bay side of the barrier islands you have a better chance of finding live snails. One of the more common in the salt marshes is the marsh periwinkle. This small roundish snail is often seen on the extended leaves of the marsh grasses. It is here during high tide to avoid predators such as blue crabs and diamondback terrapins. At low tide they will descend to the muddy bottom and feed on detritus.

The marsh periwinkle is one of the more common mollusk found in our salt marsh. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The crown conch is another frequently seen estuarine snail. With spines extending from the top whorl – it appears to have a crown, and where its common name comes from. These are predators of the bay feeding on other mollusks such as periwinkles and oysters.

The white spines along the whorl give this snail its common name – crown conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The oyster drill shell is one of the more common shells you find hermit crabs in, but the snails are out there as well. As the name implies, they use a tooth like structure called a radula to bore into other mollusk shells to feed. They are particularly problematic for non-moving oysters – and where they got their common name from.

The shell of the oyster drill.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The only slug I have encountered on our beaches is the sea hare. These slugs can be a greenish or brownish color and are about six inches in length. They lack an external shell but do not move much faster than their snail cousins. They feed on a variety of seaweeds and the color of their skin mimics the seaweeds they are feeding on. Lacking a shell, they produce a toxin in their skin to repel would be predators. They also release ink like the squid and octopus cousins.

A common sea slug found along panhandle beaches – the sea hare.

This narrative only scratches the surface of the world of snails and slugs in this part of the world. Creating a check list of species and then seeing if you can find them all is great fun.

References

The Mollusca. Sea Slugs, Squids, Snails, and Scallops. University of California at Berkley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/taxa/inverts/mollusca/mollusca.php#:~:text=Mollusca%20is%20one%20of%20the,scallops%2C%20oysters%2C%20and%20chitons..

Gastropods. University of Texas San Antonio. https://www.utsa.edu/fieldscience/gastropod_info.htm#:~:text=Gastropods%20are%20another%20type%20of,of%20the%20entire%20Mollusca%20phylum..