by Rick O'Connor | Apr 11, 2025

As we mentioned when we began writing about seaweed, seaweed and seagrass are very different. Seagrasses are true plants in the sense that they have an internal vascular system that runs water and other material throughout the plant. Like the artery and veins of animals – they are called xylem and phloem. Water in the soil is diffused through the tissue of the roots into the xylem, which moves the water up through the stem to the leave where it is used in photosynthesis. The sugars produced by photosynthesis are moved through back down into the plant by traveling through the phloem. Seagrasses produce small flowers that are pollinated by dispersing the pollen in the currents and by small invertebrates, such as amphipods and polychaetae worms. Seagrasses are true plants.

Grassbeds are also full of life, albeit small creatures.

Photo: Virginia Sea Grant

Believed to have originated as land plants, today there are about 72 species of seagrasses found around the world; seven are found in Florida; five found in the Pensacola Bay system. Though found in some open ocean systems, most seagrass beds are found in the protected waters of the estuary. They thrive in areas with low wave energy and clear water. They help stabilize the shoreline and remove pollutants from the water column. There is an abundance of marine creatures who use the seagrass beds as either a source of food, or habitat. It has been determined that at least 80% of the commercially important finfish and shellfish use seagrass beds for at least part of their life cycle.

Three of the five local species can be found in Santa Rosa Sound. Shoal grass (Halodule) has a flat blade but is very thin, between 2-3mm wide. Because it is so narrow, less surface area, it can tolerate waves better than turtle grass, and thus lives closer to the shoreline. Within the shoal grass you can find a variety of small baitfish feeding, as well as blue crabs and hermit crabs scavenging. But it does not provide the hiding spaces that the wider blade turtle grass does.

Shoal grass. One of the common seagrasses in Florida.

Photo: Leroy Creswell

Turtle grass (Thalassia) have blades that are 10mm wide. These wider blades do not handle the waves as well and thus turtle grass grows in deeper waters further off the beach. How deep they can grow is a function of the amount of sunlight reaching the bottom. In the Florida Keys turtle grass has been found at depths of 30 feet. Locally maximum depths are more likely near 10 feet. The wide blades of this grass provide surface area for a variety of small algae and invertebrates to attach. These epiphytes and epizoids are a major player in the food web of seagrass beds. Numerous invertebrates and fish feed on this “scum layer” found on the grass blades. The grazers attract low level predators such as pinfish, puffers, and sea horses. These in turn attract larger predators such as rays, speckled trout, and flounder. Manatees and sea turtles can be found here as well as sharks and the occasional bottled nose dolphin.

The wide blades of turtle grass provide habitat for a variety of epibiota.

Photo: UF IFAS

Manatee grass (Syringodium) resembles shoal grass, but the blade is round instead of flat. It can be found forming its own patches or dispersed within the other species. The abundance of this species seems to be increasing in local waters.

Gracilaria is a common epiphytic red algae growing in our seagrass beds. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Widgeon grass (Ruppia) is a common seagrass found in the upper portions of our estuary. Though it can live in the higher salinities near Pensacola Beach, it can also tolerate the lower salinities of the upper bays and thus, with less competition, does very well here. It also resembles shoal grass but differs in that the blade branches as it grows. Like all seagrass beds, widgeon grass can support a lot of marine creatures and increase the overall biodiversity of the bay.

The branched leaves of the widgeon grass.

Since the 1950s the northern Gulf coast has witnessed a decline in seagrass acreage. The decline was caused by a combination of factors. One, increased sedimentation with stormwater and development. In some cases, the seagrass was literally buried and in others the sediment decreased water clarity which decreased needed sunlight. Two, shrimp trawls. At one time shrimpers could pull their trawls through the grass to catch shrimp. This ripped and destroyed much of the habitat and the state closed shrimping in all grassbeds. Three, seawalls. Waves reflecting off the seawalls increased the wave energy within the Sound to a point that seagrass could not tolerate it. The landward edge of many grassbeds began to retreat from these seawalls reducing the overall acreage of the seagrass bed. Four, prop scars. Boats running through the grassbeds will cut deep scars in the grass that reach the sand beneath. It can take up to 10 years for the system to restore itself. And, with more boats out there, there are more scars. Five, the increase in the mass of drift algae settling on the grasses. These drift algae populations increase with increased nutrients being discharged into the Sound from land-based run-off. Drift algae cover the grasses decreasing their ability to absorb much needed sunlight.

Monitoring in recent years has shown that our seagrasses are trying to restore themselves and some beds have increased in size during the last couple of decades. Monitoring continues.

References

Florida Seagrass. Florida Department of Environmental Protection. https://floridadep.gov/rcp/seagrass.

Potouroglou, M., Pedder, K., Wood, K., Scalenghe. 2022. What to Know About Seagrass, the Ocean’s Overlooked Powerhouse. World Resources Institute. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/plants-algae/seagrass-and-seagrass-beds#:~:text=Seagrasses%20produce%20the%20longest%20pollen,flower%20and%20fertilization%20takes%20place.

Seagrass and Seagrass Beds. Ocean, Find Your Blue. Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History. https://ocean.si.edu/ocean-life/plants-algae/seagrass-and-seagrass-beds#:~:text=Seagrasses%20produce%20the%20longest%20pollen,flower%20and%20fertilization%20takes%20place..

Seagrass Species Profiles. South Florida Aquatic Environments. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://floridadep.gov/rcp/seagrass.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 14, 2025

If green algae are difficult to find in the northern Gulf because most prefer freshwater, and rocky shorelines, brown are difficult because the group prefers colder water, as well as rocky shorelines – but we do have some here.

Brown algae get their color because the ratio of photosynthetic pigments in their cells favors the xanthophylls – which produces a yellow-brown color. Like most macroscopic algae, they attach to the hard bottom using a holdfast and then extend their stipe and blade into the water column to absorb light. One group of brown algae are the largest of all seaweeds, the giant kelp Macrocystis. In the nutrient rich waters off California this seaweed will grow up to one foot a day and can reach heights of up to 175 feet tall. Since seaweeds do not possess true stems, or any wood, what holds this giant seaweed up are air filled bladders called pneumatocysts – structures found on other brown algae and are unique to the group.

The largest, fastest growing seaweed – giant kelp.

Photo: NOAA

Many species are popular with seafood dishes, such as Nori. Others produce a carbohydrate known as algin that is extracted and used as a food additive. You may have heard “ice cream has seaweed in it”. What it actually has is algin. This carbohydrate acts as a smoothing agent for products. Solids should be solid – like frozen ice cream – but, as you know, we do not want our ice cream solid. So, for a period of time, the algin keeps the ice cream smooth and creamy. Algin is used in toothpaste, lipstick, and icing on cakes for the same reason.

But along the northern Gulf coast, brown algae are not common. Despite preferring marine waters, they do prefer colder water and, like most seaweeds, need a hard substrate to attach their holdfast. But by exploring our local rock jetties and seawalls we do find some. One in particular is the common rock weed – Dictyota. This sessile seaweed branches out and resembles small trees. But the most common, and most recognized brown algae on our coast is Sargassum.

The brown algae Dictyota.

Photo: NOAA

Sargassum has found a way to deal with an environment where little hard bottom is present. Using the characteristic air bladders allows it to float at the surface to absorb the much needed sunlight. Because of this ability to float, Sargassum can be found all across the oceans, and often form large mats that cover miles of open sea and extend several feet down. It actually creates a whole new ecosystem in the middle of the sea. The major ocean currents rotate like a hurricane and, like a hurricane, the center – the “eye” – is calm. Within this calm huge mats of Sargassum collect. The ancient sailors called the center of the Atlantic Ocean the “Sargasso Sea”. But as the large currents spin, sections of this large mat “spin off” and are pushed across the ocean. Much of it heads towards Florida, the Gulf, and eventually to the northern Gulf.

If you grab a mask and snorkel and swim within the Sargassum before it reaches the waves, you will encounter a whole community of creatures that live here. Sargassum crabs, Sargassum fish, and even seahorses live within it. There are shrimps, worms, and even mollusks. When baby sea turtles head offshore after hatching, many seek out these Sargassum mats to both hide in, and feed within. They will spend their youth here before returning back to shore for different prey.

However, once many of these creatures sense the waves breaking, and now the mat is about to wash ashore, they will move to mats further offshore. That said, picking through the Sargassum on the beach may still yield some interesting creatures.

Sargassum.

In recent years the amount of Sargassum washing ashore has increased and become problematic – particularly in southeast Florida and the Florida Keys. At times, mounds three feet high have been found. Those communities are working on methods to deal with the problem. But here locally, these mats are a new world to explore.

References

Giant Kelp. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/giant-kelp.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 14, 2025

Members of the seaweed group Rhodophyta – the red algae – prefer warmer marine waters. Though the diversity and abundance of seaweeds in the northern Gulf is low due to unsuitable substrate for them to attach to, the red algae may be the most diverse group we have.

One publication produced by Florida Gulf Coast University1 lists 20 different species of seaweeds in our state; 13 (65%) are red algae. Most of them a thin bladed. Some are smooth and others have “hooks” along their blades. Some species are drift algae – drifting in the water and settling on seagrasses similar to how Spanish moss settles on oak trees. Most are found in south Florida, due to the hard limestone bottom found there, but there are species in our area attached to rock jetties and seawalls.

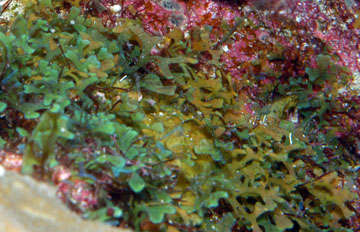

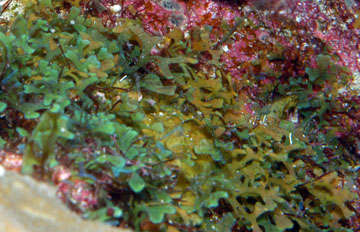

We also have drift algae here. Large clumps of red algae known as Gracilaria are found atop seagrasses. Though they provide suitable habitat for fish and invertebrates, but they are not so good for the seagrass. These drift algae cover the grass not allowing the much needed sunlight. They also compete with our seagrasses for available nutrients in the water column. Volunteers in our local seagrass citizen science monitoring project – Eyes on Seagrass – record whether drift algae are present when they are monitoring as well as noting whether it was abundant or not. We have noticed that it may be abundant in one season and not another. We have also noticed that when it is abundant in Santa Rosa Sound it may not be present in Big Lagoon – and vice versa.

Gracilaria is a common epiphytic red algae growing in our seagrass beds. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though there is no commercial use for the red algae in our area, there are many species popular in the seafood industry. Nori is a popular seaweed used in Sushi dishes and Dulce is said to help with sea sickness.

Nori is a popular red algae in the seafood industry.

In the last three posts we have introduced you to the seaweeds of the northern Gulf. Though neither diverse nor abundant, they are present and do play an important role in the ecology of our area. I recently witnessed mallard ducks feeding off of red algae on a rock jetty on Pensacola Beach. In our next article we will turn our attention to the only group of true submerged marine plants in our area – the seagrasses.

References

1 Algae Identification Guide. Florida Gulf Coast University. https://hillsborough.wateratlas.usf.edu/upload/documents/FGCU_Algae_Identification_Guide.pdf

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 14, 2025

With this article we will shift from the microscopic creatures of the Gulf of Mexico to the macroscopic ones – ones you can see without a microscope. We will begin with the simplest and most primitive of macroscopic creatures – the seaweeds.

Many locals see the grass washed ashore along the Intracoastal Waterway and call this seaweed, but it is in fact seagrass. Seaweed differs from seagrass in that they are not true plants. True plants are vascular – meaning they have a series of “veins” running through their body called xylem and phloem. These veins move water and material throughout the body – similar to the arteries and veins of an animal. But seaweeds lack this “circulatory” system, rather they absorb water through their tissues and must live in the water environment to do this. Seaweeds lack leaves, stems, and roots. They do not produce seeds or flowers, but they do require sunlight and nutrients and conduct photosynthesis as true plants do. When I was in college seaweed was considered simple plants – just nonvascular ones. Today biologists believe they are too simple to be considered plants and thus are a group existing between the microscopic phytoplankton and the true vascular plants we know from our lawns and forests. They are often called algae as well as seaweed.

Mats of Sargassum on a south Florida Beach.

Photo: University of Florida

Biologists divided the seaweeds into divisions based on their color, which is determined by the photosynthetic pigments they have for photosynthesis. Compared to my college days, the classification of green algae is quite complex. The entire group was once placed in the Division Chlorophyta. Today, most sources consider only the marine forms of green algae in the group Chlorophyta, with numerous other groups consisting of thousands of species. Most green algae live in freshwater and are believed to be the group that led to the land plants we are familiar with. Their photosynthetic pigments include chlorophyll and a and b but also carotene and xanthophyll. The pigments are dominated by the chlorophylls – hence their green color – and the ratio of chlorophyll to carotene and xanthophyll is the same as the plants you find in your yard – hence the argument they led to the evolution of land plants.

Green algae – or any of the seaweeds – are not as common along the northern Gulf of Mexico as you find on other coasts. Not having true roots, stems, or leaves, seaweeds must attach themselves to the seafloor using a suction cup type structure called a holdfast. To attach, the holdfast must have a rock of some type. Along the rocky shores of Maine and California, they are quite common. Even with the limestone rock of south Florida you can find these. But the fine quartz sand of the northern Gulf of Mexico is not as inviting to them. That said, we do find them here and most are found on man-made structures such as jetties, seawalls, and artificial reefs – I found one attached to a beer can.

Of all of the green algae that exist in Florida, I have only encountered three. One is called “sea lettuce” in the genus Ulva. Attached to rock jetties and seawalls, it looks just like lettuce and is beautiful, brilliant green in color. It grows to about seven inches in height and is used as a food source in different countries. It can become a problem if local waters are high in nutrients due to pollution from land sources. It will grow abundantly, reducing habitat for other species, and wash ashore during storms where it breaks down releasing gases that can be toxic to shore life and humans. I first encountered it growing on the rock jetties at St. Andrews State Park in Panama City, but it does grow on local hard structures.

Sea Lettuce.

Photo: University of California

“Dead Man’s Fingers” – Codium – is another green algae I first encountered it on the jetties of St. Andrews. The thick finger-like projections of this seaweed extending from the rocks did resemble a glove – or the fingers of a dead man within the rocks. Some species around the world are used for food. But I could not find any references that it is here.

“Deadman’s Fingers”.

Photo: iNaturalist

The third species of green algae I have seen locally is known as the “Mermaids Wine Glass” – Acetabularia. This beautiful seaweed is relatively small and does resemble a wine, or martini glass. They are quite abundant in south Florida and is the one I found growing on a beer can submerged in Santa Rosa Sound.

“Mermaid’s Wineglass”

Photo: Project Noah

Though seaweeds in general are harder to find along the northern Gulf coast, they are fun to search for and do play a role as primary producers here.

References

Green Algae. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Green_algae.

Deadman’s Fingers. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/dead-mans-fingers.

Introduction to Green Algae. University of California/Berkley. https://ucmp.berkeley.edu/greenalgae/greenalgae.html.

Ulva Lactuca. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ulva_lactuca.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 24, 2025

What are meroplankton? How do they differ from regular plankton?

In the plankton world there are those that are plankton (drifters) their whole lives – holoplankton – and those who are plankton for only part of their lives – meroplankton. Most know the meroplankton as larva – the early stages of large creatures like fish, crabs, and shrimp. When you pull a plankton net through the waters of the Gulf of Mexico you will collect a lot of meroplankton – and yes… they are food for the plankton feeders just as the other forms of plankton are. Like most of the holoplankton, most are microscopic and swim through the water using cilia or flagella. Like copepods, they are multicellular and are considered true animals. Here are a few that you could find in a plankton sample…

Planula larva

These are the larva of jellyfish, sea anemones, and corals. They are ciliated cells that move through the water column until they metamorphose into the adult forms. Most will settle out on hard substrate on the seafloor and develop into a flower-like structure called a polyp. Some grow into adult polyps – like sea anemones and corals – while others will go through a second stage and become swimming medusa – the jellyfish.

Trochophore larva

This is another ciliated larval form that is the first stage of some mollusk, annelid worms, and nemertean worms.

Veliger larva

This is a ciliated larval form of several mollusk. Those that go through the veliger stage begin as trochophores. Some go through the trochophore stage while in the egg, others hatch and go through the trochophore before metamorphosizing into the veliger. The veliger stage will develop the characteristic mollusk shell, and many will develop a foot which can be used in locomotion on the seafloor searching for suitable habitat.

The veliger stage of many mollusks.

Photo: NOAA.

Nauplius larva

This is the first stage of a crustacean. It is very hard to tell which crustacean the nauplius will become but they do resemble crustaceans with segmented body parts and an exoskeleton. Most crustaceans will molt into the zoea stage, and some then into a megalops stage, before becoming the adult.

This is the megalops stage of a crab.

Photo: University of California Irvine.

Bipinnaria larva

Another ciliated larval form that will eventually become an echinoderm – starfish, sea urchin, sand dollar.

Bipannaria are the larval stage of starfish and sand dollars.

Photo: NOAA.

Ichthyoplankton

Most of the fishes in the northern Gulf of Mexico begin life as meroplankton as well – these are called “ichthyoplankton” and are quite abundant in a plankton sample. Even large fish, such billfish and swordfish, begin life at this stage.

Most fish in the northern Gulf begin their lives as tiny plankton.

Photo: NOAA.

The first nine post in this series have been about microscopic creatures found in the northern Gulf. It goes without saying that there are literally thousands of other forms of plankton we did not mention. It is also important to mention how important these creatures are to the health of the Gulf and why they were as much of a concern during the oil spill as were dolphins, sea turtles, and sea birds. As the plankton go… so goes the Gulf. We will now turn our attention to the larger creatures – ones you do not need a microscope to see.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 17, 2025

So far in this series we have been discussing microscopic creatures in the northern Gulf of Mexico that are single celled – though many may be linked together in chains. In this article we will begin discussing microscopic creatures that are multicellular.

When you do a plankton tow in the northern Gulf, and have a look under the microscope, you will notice most of the moving/swimming plankton are these bug-looking creatures scientists call copepods. The Latin origin of their name (oar-foot) comes from the motion of their swimming legs, which resembles rowing with an oar. They twist and turn all within the field of view, moving quite fast. You will not miss them.

One of the most common creatures in the northern Gulf. The copepod.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

It has been stated that the copepods produce some of the largest biomass in the oceans, there are TONS of them within the water column. They swim all through the water column feeding on the phytoplankton we have already discussed in this series. They play a very important role in the food chain connecting the photosynthetic phytoplankton – the “grasses of the sea” – with the consuming animals of the northern Gulf. It has been stated that the copepods are most likely in every creature’s food chain – making them one of the most important members of the northern Gulf of Mexico community. In addition to connecting the marine animals to the primary producers, they also are important at removing carbon from the surface waters of the oceans, reducing the negative impacts of excessive carbon in the atmosphere.

As mentioned, they are multicellular but still microscopic. We also mentioned they look like bugs and are in the Phylum Arthropoda along with the true bugs. Arthropods have jointed legs, antennae, and an exoskeleton that must be shed during growth – and this is the case with the copepods. They are in the Subphylum Crustacea – indicating they are related to shrimps and crabs. Most are between 1-2mm in length but can reach lengths of 10mm and large to be seen in a glass of sea water as flecks darting about. Most have a single compound eye and, along with their antennae, can detect the movements of both predators and prey.

Many larger creatures of the northern Gulf feed on them directly – such as the plankton feeding fish and whales. But most include them as a lower part of their food chain. Copepods can sense the presence of such predators and are quite fast swimmers. They have been clocked at 295 feet in one hour – which is equivalent to a human swimming at 50mph!

Though you will never see them when you visit the beaches, they are one of the most abundant, and ecologically important, creatures in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Copepods. National Museum of Natural History. https://naturalhistory.si.edu/research/invertebrate-zoology/research/copepods.

Copepod. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/copepod.

Walter, T.C.; Boxshall, G. (2024). World of Copepods Database. Accessed at https://www.marinespecies.org/copepoda on 2024-11-17. doi:10.14284/356.