by Julie McConnell | Oct 27, 2015

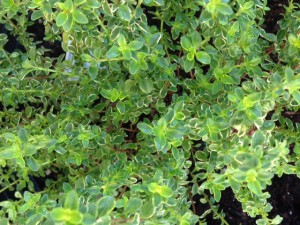

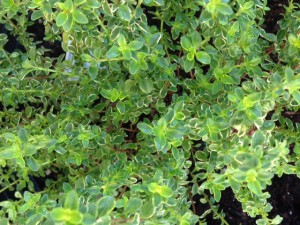

Variegated lemon thyme. Photo: JMcConnell, UF/IFAS

If you have ever thought about gardening but feel too intimidated to give it a try, consider starting with a herb garden!

Culinary herbs are generally very easy to grow and very forgiving of the neglectful gardener. They have relatively few pest or disease problems and thrive in hot climates on poor soils. An added benefit of growing herbs is that some parts are edible and can really liven up a plain dish.

Just like with other plants, there are both annual and perennial herbs. Annuals only live for one season and will need to be replanted or allowed to go to seed for the next season’s plant. An example of an easy to grow herb with an annual life cycle is basil. Basil comes in many different flavors and can be purchased as a transplant (small plant) or grown from seed. It performs well in warm weather and will be killed by a hard frost. Basil grows well in part to full sun and when it flowers it is attractive to bees and other pollinators. If you allow it to go to seed, you will have more plants throughout the growing season and more the following year.

Some perennial herbs that are easy to grow are rosemary, thyme, and mint. All of these plants can live for many years in the home garden. Rosemary and thyme like sunny spots but have very different growth habits. Rosemary will grow into a large woody shrub while thyme is low growing and hugs the ground. Both like full sun and good drainage. Another perennial herb that fits into shady sites with moist soil is mint. Mint has a vining habit and can either trail over the edges of pots or can form a dense mat in a flower bed. It will root wherever the stem touches the ground, so it is also easy to divide plants and share with friends.

To learn more about herbs read Herbs in the Florida Garden or attend our upcoming class “More Cooking With Herbs” where you will learn how to grow and cook with them! Class will be held on Saturday, November 14th from 9 a.m. – 12 noon. Pre-registration and payment of $10 is required no later than November 9th to attend the class. For more details or to register, call our office at 850-784-6105.

by Beth Bolles | Oct 27, 2015

Fall is a wonderful season for viewing wildflowers and there are many flower colors brightening our landscapes and roadsides. Amongst all the color there is one wildflower, the Rayless sunflower (Helianthus radula) that may not be nearly as showy but is very interesting in the landscape.

Flower heads have disk flowers but no rays. Photo by Beth Bolles

Many people will discover the Rayless sunflower in a moist area near the ditch or a drainage area. It has a basal set of leaves that blend into the surrounding grass. In summer a leafless stem about will emerge that is topped by a round flower with discs but no rays. It mostly appears brown but may offer a tinge of red or purple from the disc flowers.

Rayless sunflower in mass. Photo by Jeff Norcini

Not everyone will appreciate the beauty of the rayless sunflower. It will be visited by pollinators and offers an attractive contrast to the greens of surrounding plant material. It is a plant suited to its preferred habitat and an understated treasure among native wildflowers.

by Carrie Stevenson | Oct 20, 2015

Contrary to popular belief, stormwater runoff—not industrial discharge—is the primary source of water pollution in Florida. During a rain, anything on the ground can be picked up, carried via water, and taken downstream to the nearest body of water. While newer construction projects require stormwater treatment (including detention ponds or newer techniques such as pervious pavement and biofiltration), the infrastructure in older coastal communities often pipes rainwater directly into local creeks, bayous, and bays.

A large storm drain empties into Pensacola Bay. Photo Credits: Carrie T. Stevenson, IFAS Extension

Pollutants contained in stormwater vary greatly in type and potential for damage. E. coli and fecal coliform bacteria from pet waste and septic tanks frequently cause closures of local swimming holes due to high bacteria counts. Heavy metals from car exhaust, along with oil and grease from roads and parking lots can contaminate fish. Litter from yards, roadsides, and coastal areas can trap, injure, or kill wildlife. Nitrogen and phosphorus from excess fertilization and organic debris can result in water bodies with oxygen deprivation, algae blooms, and in worst case scenarios, fish kills. Even sediment and clay from dirt roads, eroding property, and construction sites can end up downstream, filling in creek bottoms or seagrass beds.

When creeks are filled with sediment, the small invertebrates that make up the bottom of the food chain are smothered, while turbidity (cloudy water resulting from sediment particles) and sedimentation in grass beds reduces the amount of sunlight reaching the grasses and prevents growth.

Pervious pavement allows rainwater to filter into the soil instead of running over parking lots. Photo Credits: Christopher J. Martinez, UF Agriculture and Biological Engineering.

The most difficult aspect of preventing stormwater pollution, also referred to as “non-point source” pollution, is that it doesn’t come from a single source but is the result of numerous cumulative impacts. However, there are many ways that individuals can reduce their unintentional contribution to this problem. When it’s time to fertilize plants, read and follow the label, and if you have questions, contact an extension agent to make sure you understand the proper amount to apply. If you live on a dirt road that crosses a creek, encourage your neighbors to agree to having it paved—many county projects are held up by a handful of homeowners who don’t see the benefits to having a rural road paved. Be sure to clean up pet waste, and if you’re on a septic system and have the capability to convert to sewer treatment, take advantage of that option.

While it can seem that these minor changes can’t make a big difference, there is much evidence to the contrary. The US Environmental Protection Agency recently recognized the success of a Florida community that took assertive stormwater pollution prevention measures. As a result of their actions, a polluted water body, Roberts Bay (Sarasota) was removed from the state’s list of impaired waters.

http://water.epa.gov/polwaste/nps/success319/fl_roberts.cfm

by Matt Lollar | Oct 20, 2015

Warm and wet weather in the Florida Panhandle presents the optimum conditions for the development of bacterial gall on loropetalums. Shoot dieback is usually the first and most noticeable symptom of the disease. The dieback can be followed down the branch to dark colored, warty galls that vary in size. The galls enlarge and eventually encircle the branch resulting in branch or plant death. Olive, oleander, and ligustrum are also hosts for the bacteria that causes the galls, Pseudomonas savastanoi.

Dieback symptoms on loropetalum leaf from bacterial gall. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS

Bacterial gall on loropetalum. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS

The most common source of bacterial gall is from the plant nursery. Prior to purchase, inspect plants for galls near the soil line. If plants have already been installed in the landscape, remove any branches containing galls. Pruning cuts should be made several inches below the gall. After each cut, dip pruners in a 10% bleach solution or spray with isopropyl alcohol to avoid spreading the disease to other parts of the plant or other plants. Prune during dry weather.

The best control for bacterial gall is selecting good quality plant material. For more information on this disease, please visit: Bacterial Gall on Loropetalum. More information on disease issues in the home landscape can be found at: Lawn and Garden Plant Diseases.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 20, 2015

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees become. Sapium sebiferum, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Sapium sebiferum, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida.

As the trees begin to turn various shades of red, many people begin to inquire about the Popcorn trees. While their autumn coloration is one of the reasons they were introduced to the Florida environment, it took years for us to realize what a menace Popcorn trees become. Sapium sebiferum, the Chinese tallowtree or Popcorn tree, was introduced to Charleston, South Carolina in the late 1700s for oil production and use in making candles. Since then, it has spread to every coastal state from North Carolina to Texas, and inland to Arkansas. In Florida it occurs as far south as Tampa. It is most likely to spread to wildlands adjacent to or downstream from areas landscaped with Sapium sebiferum, displacing other native plant species in those habitats. Therefore, Chinese tallowtree was listed as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Noxious Weed List (5b-57.007 FAC) in 1998, which means that possession with the intent to sell, transport, or plant is illegal in the state of Florida.

Although Florida is not known for the brilliant fall color enjoyed by other northern and western states, we do have a number of trees that provide some fall color for our North Florida landscapes. Red maple provides brilliant red, orange and sometimes yellow leaves. The native Florida maple, Acer saccharum var. floridum, displays a combination of bright yellow and orange color during fall. And there are many Trident and Japanese maples that provide striking fall color. Another excellent native tree is Blackgum, Nyssa sylvatica. This tree is a little slow in its growth rate but can eventually grow to seventy-five feet in height. It provides the earliest show of red to deep purple fall foliage. Others include Persimmon, Diospyros virginiana, Sumac, Rhus spp. and Sweetgum, Liquidambar styraciflua. In cultivated trees that pose no threat to native ecosystems, Crape myrtle, Lagerstroemia spp. offers varying degrees of orange, red and yellow in its leaves before they fall. There are many cultivars – some that grow several feet to others that reach nearly thirty feet in height. Chinese pistache, Pistacia chinensis, can deliver a brilliant orange display.

There are a number of dependable oaks for fall color, too. Shumardi, Southern Red and Turkey are a few to consider. These oaks have dark green deeply lobed leaves during summer turning vivid red to orange in fall. Turkey oak holds onto its leaves all winter as they turn to brown and are pushed off by new spring growth. Our native Yellow poplar, Liriodendron tulipifera, and hickories, Carya spp., provide bright yellow fall foliage. And it’s difficult to find a more crisp yellow than fall Ginkgo, Ginkgo biloba, leaves. These trees represent just a few choices for fall color. Including one or several of these trees in your landscape, rather than allowing the Popcorn trees to grow will enhance the season while protecting the ecosystem from invasive plant pests.