by Matt Lollar | Mar 25, 2021

Article written by Dr. Gary Knox, North Florida Research & Extension Center – Quincy, FL.

‘Gumpo Pink’ flowers are 3 inches in diameter and are pink with purplish pink dots and occasional white blotches on petals.

Background

In the times before re-blooming azaleas like Encore®, Bloom-A-Thon® and others, Satsuki azaleas were valued for late flowering that extended the azalea “bloom season”. Even with modern re-blooming azaleas, Satsuki azaleas still are appreciated as refined evergreen shrubs for the sophisticated garden or discerning plant collector.

“Satsuki” means “Fifth Month” in Japanese, corresponding to their flowering time in much of Japan. These azaleas were developed hundreds of years ago from their native Rhododendron indicum and R. eriocarpum. The Japanese selected cultivars more for their form and foliage than for flowering. These beloved plants were used in gardens as sheared boxwood-like hedges or pruned into rounded mounds that might resemble rocks or boulders in classical Japanese gardens. Their size and form also made them well adapted for training as bonsai. Most of the Satsuki azaleas in America were introduced in the 1930s by USDA.

Description

Satsuki azaleas are small evergreen shrubs that flower in April and May in north Florida, long after most older type azaleas have finished. Satsuki azaleas also are known for producing large, mostly single flowers up to 5 inches in diameter in colors of white, pink, red, reddish orange and purple. Often the flowers will include stripes, edging, blotches, spots or flecks of contrasting colors (Sometimes all on the same plant!) with more than 20 different color patterns recorded.

Satsuki azaleas have an elegant subtle charm, quite unlike the flashy, over-the-top, heavy blooming all-at-once Southern Indica azaleas like ‘Formosa’ and ‘George L. Taber’. Typically, Satsuki azaleas display a few large blooms at a time, allowing one to better appreciate their size and color patterns as contrasted against their fine-textured, dark green leaves. To make up for a less boisterous display, Satsuki azaleas flower over a longer timeframe, averaging about 8 weeks, with some flowering an amazing 14 weeks. In another contrast, most Satsuki azaleas grow smaller in size, in my experience reaching about 3 feet tall and wide in a five-year timeframe. The rounded to lance-shaped leaves of Satsuki azaleas also are demure, ranging in length from just ½ inch to no more than 2 inches.

Culture

Satsuki azaleas enjoy the same conditions as most other azaleas: light shade and moist, rich, well-drained soil. Mulch regularly to maintain organic matter and help hold moisture. Fertilize lightly and keep the roots evenly moist. Minimal to no pruning is required. Satsuki azaleas also are well adapted to container culture. Their small size and fine textured leaves make these a favorite for bonsai enthusiasts since their small leaves, branching habit and mounded form naturally make them look like miniature mature “trees”.

Sources and Cultivars

Look for Satsuki azaleas in spring at garden centers or year-round at online nurseries. There are hundreds of cultivars but some popular types to look for include:

Gumpo Pink – 3-in. diameter light pink flowers with purplish pink dots and occasional white blotches

Gumpo White – 3-in. diameter white flowers with occasional pink flakes and light green blotches

Gyokushin – 3-in. diameter flowers are predominantly white but with light to dark pink dots and blotches

Higasa – flowers are 4 to 5 inches in diameter and are purplish pink with purple blotches

Shugetsu – also called ‘Autumn Moon’, 3-in. diameter flowers are white with a broad, bright purplish-red border

Tama No Hada – flowers are 4 to 5 inches in diameter and are white to pink with deep pink stripes; usually flowers in fall as well as spring

Wakaebisu – 2.5-in. diameter flowers are “double” (hose-in-hose) and are salmon pink with deep pink dots and blotches; this also flowers in fall as well as spring

References:

Chappell, M. G.M. Weaver, B. Jernigan, and M. McCorkle. 2018. Container trial of 150 azalea (Rhododendron spp.) cultivars to assess insect tolerance and bloom characteristics in a production environment. HortScience 53(9-S): S465.

‘Gumpo Pink’ flowers are 3 inches in diameter and are pink with purplish pink dots and occasional white blotches on petals.

‘Gyokushin’ flowers are white with occasional pink flecks and light green blotches.

‘Shugetsu’ has 3-inch flowers that have bright purplish-red border on edges of petals.

Galle, Fred C. Azaleas. 1985. Timber Press, Portland, Oregon. 486 pp.

by Matt Lollar | Mar 4, 2021

Plant with Purpose: Written by Rachel Mathes

Last spring, we were all ready to host another Open House and Plant Sale on Mother’s Day weekend. When the realities of the pandemic became clear, we canceled the event for the safety of everyone involved. We typically have more than 500 visitors and dozens of volunteers on site. This year we are happy to announce we have adapted our annual fundraiser to a monthly learning and growing opportunity for the whole community.

Master Gardener Volunteer Jeanne Breland is growing native milkweed in her monarch exclusion fortress for a Plant with Purpose talk and sale in the spring. Previous years’ milkweed have been eaten by monarch caterpillars before the sale so Jeanne has built her fortress to get the best results. Photo by Rachel Mathes

Our Master Gardener Volunteers will be teaching Thursday evening classes on particular plant groups throughout the year in our new series: Plant with Purpose. Topics will range from milkweed to shade plants to vegetables and herbs for different seasons. Attendees can attend the talks for free and grow along with us with the purchase of a box. These boxes are modeled after community supported agriculture (CSA) boxes you can purchase from local farms. Buyers will get a variety of the plants discussed in the plant lesson that week. For example, in our first event, Growing a Pizza Garden, we will have two tomato plants, two pepper plants, and one basil plant available for $20. Throughout the year, prices and number of plants will vary depending on the topic.

We hope with this new model of presentations and plant sales will enable us to remain Covid-safe while still bringing horticulture education to the community. Classes will be held on Thursday evenings from 6-7 pm via Zoom. Register on our Eventbrite to get the Zoom link emailed to you before each talk. Plant pick up will be the following Saturday from 10 am to noon. Master Gardener Volunteers will load up your plant box in a contact-free drive thru at the UF/IFAS Leon County Extension Office at 615 Paul Russell Rd.

Propagation of angel wing begonia and other plants by Joan Peloso, Master Gardener Volunteer.

Master Gardener Volunteers are already growing plants for you to purchase throughout the year. Landscape plants, herbs, vegetables, shrubs and even trees will be available later in the year. Funds raised from this series help fund our Horticulture programming. Some notable programs that will benefit from Plant with Purpose include our Demonstration Garden, 4-H Horticulture Club, the Veterans’ Garden Group at the VA Tallahassee Outpatient Clinic, and various school gardens we help support throughout Leon County.

In the last year, we have adapted many of our programs to meet virtually, and even created new ones like our Wednesday Webinar series where we explore different horticulture topics twice a month with guest speakers from around the Panhandle. While we still can’t meet in person to get down in the dirt with all of our community programs, we hope that the Plant with Purpose series will help fill the hole left by our cancelled Open House and Plant Sale. Join us for the first installment of Plant with Purpose on Thursday March 18th from 6-7pm. Pick up for purchased plant boxes will be Saturday March 20th from 10am-noon.

To register for this event and other events at the Leon County Extension Office, please visit the Leon County Extension Office Events Registration Page.

by Matt Lollar | Feb 18, 2021

It’s mid-February, cloudy, and cold. It’s time to get outside and take cuttings for fruit and nut tree grafting. The cuttings that are grafted onto other trees are called scions. The trees or saplings that the scions are grafted to are called rootstocks. Grafting should be done when plants start to show signs of new growth, but for best results, scion wood should be cut in February and early March.

Scion Selection

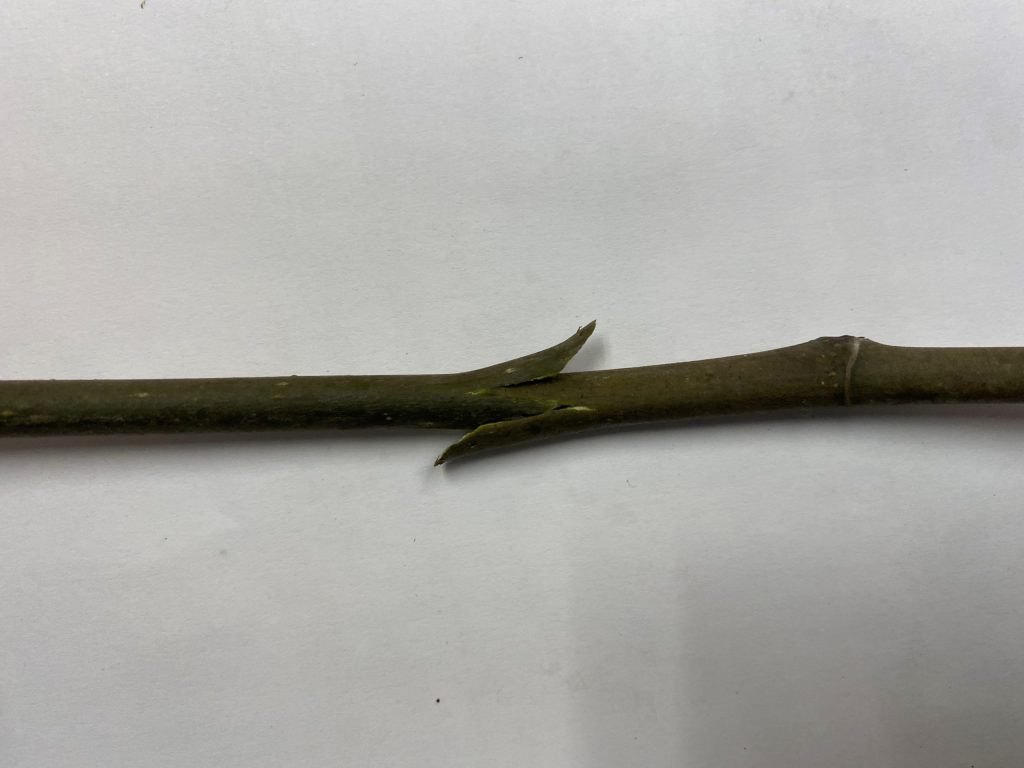

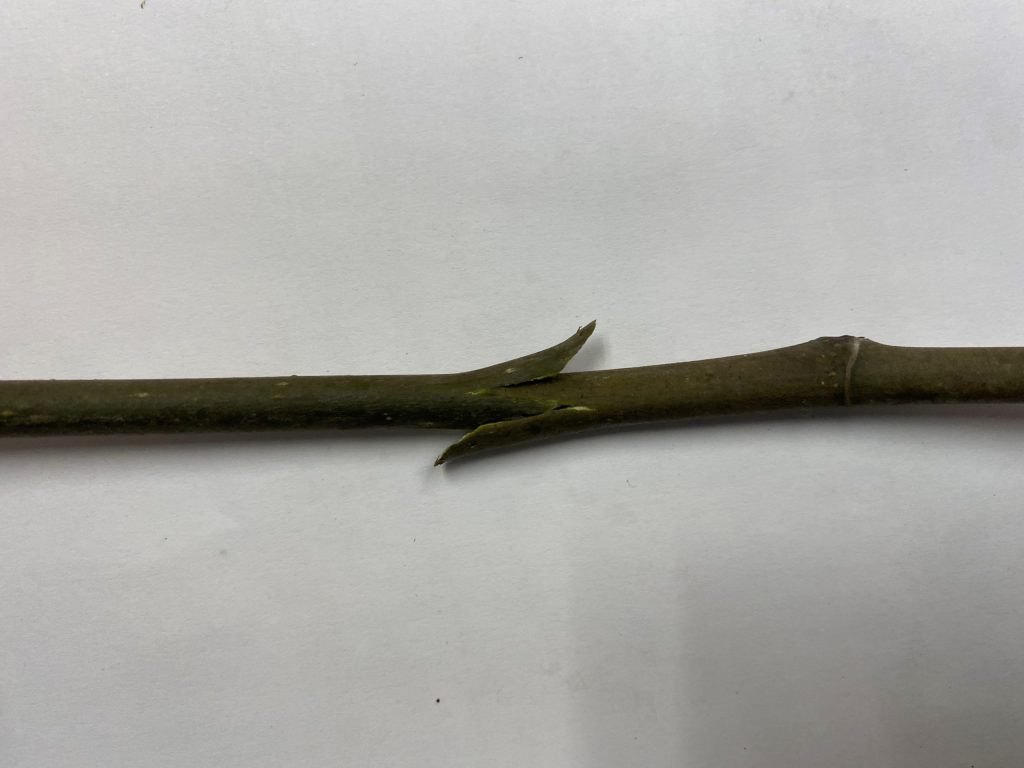

Straight and smooth wood with the diameter of a pencil should be selected for scions. Water sprouts that grow upright in the center of trees work well for scion wood. Scions should be cut to 12-18″ for storage. They should only need two to three buds each.

Scions ready for grafting. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Scion Storage

Scions should be cut during the dormant season and refrigerated at 35-40°F until the time of grafting. If cuttings are taken in the field or far from home, then simply place them in a cooler with an ice pack until they can be refrigerated. Cuttings should be placed in a produce or zip top bag along with some damp paper towels or sphagnum moss.

Grafting

It is better to be late than early when it comes to grafting. Some years it’s still cold on Easter Sunday. Generally, mid-March to early April is a good time to graft in North Florida. Whip and tongue or bench grafting are most commonly used for fruit and nut trees. This type of graft is accomplished by cutting a diagonal cut across both the scion and the rootstock, followed by a vertical cut parallel to the grain of the wood. For more information on this type of graft please visit the Grafting Fruit Trees in the Home Orchard from the University of New Hampshire Extension.

A bench graft union. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Achieving good bench graft unions takes skill and some practice. Some people have better success using a four-flap or banana graft technique. This type of graft is accomplished by stripping most of the bark and cambium layer from a 1.5″ section of the base of the scion and by folding the back and removing a 1.5″ section of wood from the top of the rootstock. A guide to this type of graft can be found on the Texas A&M factsheet “The Four-Flap Graft”.

Grafting is a gardening skill that can add a lot of diversity to a garden. With a little practice, patience, and knowledge any gardener can have success with grafting.

by Matt Lollar | Dec 9, 2020

A planted tree with water retention berm. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Often, Extension agents are tasked with evaluation of unhealthy plants in the landscape. They diagnose all sorts of plant problems including those caused by disease infection, insect infiltration, or improper culture.

When evaluating trees, one problem that often comes to the surface is improper tree installation. Although poorly installed trees may survive for 10 or 15 years after planting, they rarely thrive and often experience a slow death.

Fall/winter is an excellent time to plant a tree in Florida. Here are 11 easy steps to follow for proper tree installation:

- Look around and up for wire, light poles, and buildings that may interfere with growth;

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible;

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk;

- Slide the tree carefully into the planting hole;

- Position the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface;

- Straighten the tree in the hole;

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball;

- Slice a shovel down in to the back fill;

- Cover the exposed sides of the root ball with mulch and create water retention berm;

- Stake the tree if necessary;

- Come back to remove hardware.

Digging a properly sized hole for planting a tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Removing synthetic material from the root ball. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Straightening a tree and adjusting planting height. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida – Santa Rosa County

For more detailed information on planting trees and shrubs visit this UF/IFAS Website – “Steps to Planting a Tree”.

For more information Nuttall Oaks visit this University of Arkansas Website.

by Matt Lollar | Nov 4, 2020

From time to time we get questions from clients who are unsatisfied with the flavor of the fruit from their citrus trees. Usually the complaints are because of dry or fibrous fruit. This is usually due to irregular irrigation and/or excessive rains during fruit development. However, we sometimes get asked about fruit that is too sour. There are three common reasons why fruit may taste more sour than expected: 1) The fruit came from the rootstock portion of the tree; 2) The fruit wasn’t fully mature when picked; or 3) the tree is infected with Huanglongbing (HLB) a.k.a. citrus greening or yellow dragon disease.

Rootstock

The majority of citrus trees are grafted onto a rootstock. Grafting is the practice of conjoining a plant with desirable fruiting characteristics onto a plant with specific disease resistance, stress tolerance (such as cold tolerance), and/or growth characteristics (such as rooting depth characteristics or dwarfing characteristics). Citrus trees are usually true to seed, but the majority of trees available at nurseries and garden centers are grafted onto a completely different citrus species. Some of the commonly available rootstocks produce sweet fruit, but most produce sour or poor tasting fruit. Common citrus rootstocks include: Swingle orange; sour orange; and trifoliate orange. For a comprehensive list of citrus rootstocks, please visit the Florida Citrus Rootstock Selection Guide. A rootstock will still produce viable shoots, which can become dominant leaders on a tree. In the picture below, a sour orange rootstock is producing a portion of the fruit on the left hand side of this tangerine tree. The trunk coming from the sour orange rootstock has many more spines than the tangerine producing trunks.

A tangerine tree on a sour orange rootstock that is producing fruit on the left hand side of the tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension

Fruit Maturity

Florida grown citrus generally matures from the months of October through May depending on species and variety. Satsumas mature in October and taste best after nighttime temperatures drop into the 50s. Most tangerines are mature in late November and December. Oranges and grapefruit are mature December through April depending on variety. The interesting thing about citrus fruit is that they can be stored on the tree after becoming ripe. So when in doubt, harvest only a few fruit at a time to determine the maturity window for your particular tree. A table with Florida citrus ripeness dates can be found at this Florida Citrus Harvest Calendar.

Citrus Greening

Citrus Greening (HLB) is a plant disease caused by the bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, which is vectored by the Asian citrus psyllid. The disease causes the fruit to be misshapen and discolored. The fruit from infected trees does not ripen properly and rarely sweetens up. A list of publications about citrus greening can be found at the link Citrus Greening (Huanglongbing, HLB).

A graphic of various citrus greening symptoms. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension