by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 6, 2017

A wooden bin is easy to use for composting kitchen and yard waste. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Fall is the time of year many of us spend countless hours raking leaves and pine straw, piling them up, watching kids jump into the piles (then re-raking!), and bagging them up for disposal. However, what you may not have considered is that all of those materials are ideal fertilizer for your lawn and garden.

Composting is an excellent way to recycle yard waste, and now that leaves are dropping, you’ve got plenty of material to recycle. Vegetable gardens and landscapes alike can benefit from a generous dose of compost now and then. A free source of much-needed nutrients in our often nutrient-poor sandy soil, organic-rich compost also loosens tight, compacted soils and helps them hold nutrients and water.

So what is compost? Basically, compost is what’s left of organic matter after microbes have thoroughly decomposed it. Among the compostable organic materials available to most homeowners are leaves, grass clippings, twigs, chopped brush, straw, sawdust, vegetable plants, culled vegetables from the garden, fruit and vegetable peelings and coffee grounds (including the paper filter) from the kitchen. Don’t add table scraps with meats or oils to your compost pile—meats especially will attract animals. Contrary to popular opinion, compost piles don’t typically smell—but if you do have an odor come from decomposing vegetables, turning the compost pile and adding dirt, grass clippings or leaves will eliminate any smell.

The organisms that do the actual composting are bacteria and fungi are microscopic, although you will also find worms and arthropods in a good compost bin. A number of companies sell “composting microbes,” but you don’t need them. Fortunately, plenty of these microbes are around already. To get started, just mix a few scoops of garden soil or compost from a previous batch into the compost pile will provide all the microbes you need to start the process. The microbes just need water, oxygen and nutrients to grow and multiply.

Rainfall will provide most of the needed moisture. You may need to hand water the pile on occasion, too, during dry times. For best results, keep the pile moist but not soggy; if you pick up a handful it should not crumble away nor drip water when squeezed. The right mix of organic matter can provide all the nutrients needed. Alternate using brown (leaves, straw) and green materials (grass clippings, vegetables) in your compost bin to provide the needed amounts of carbon and nitrogen. If the pile seems to be decomposing too slowly, raise the nitrogen level by adding a few more green materials or a handful of granular fertilizer. And the more you turn the pile, the faster it will decompose.

There are many ways to contain your composting materials, from a simple pile to a solar-heated, rotating bin and everything in between. For more information on composting and compost bin options, please see this University of Florida Extension article.

by Molly Jameson | Mar 1, 2017

Raised-bed gardening can maximize production in a small amount of space. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Want to start a vegetable garden, but don’t know where to start? Are you seeing rectangular boxes popping up all over your neighbors’ yards and wondering why? Well, I am here to spread the news of raised-bed gardening!

Raised-bed gardening is a convenient way to grow vegetables without worrying about the quality of your soil. This is because you will be bringing in a high quality soil mix to your site. Vegetable plants need nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and many other nutrients to grow and mature properly. In many Florida Panhandle soils, we either have too much sand, too much clay, and nearly always, not enough organic matter. Organic matter results from the various stages of decay of anything that was alive. Think of it as the “glue” that holds the soil together, improves both soil moisture-holding capacity and drainage, and slowly releases nutrients that become available to the plant.

Organic matter is the “glue” that will hold your soil together. Photo by John Edwards.

Although you could add nutrients and organic materials to your soil without building a raised bed, the walls of a raised bed will hold your soil in place, reduce erosion, and even help keep out weeds. Here are a few things to consider when planning the installation of a raised-bed garden:

Location

The most important thing to consider when picking your location is sunlight. Vegetable plants need a lot of direct sunlight for optimum production. Leafy vegetables (lettuce, kale, arugula) can tolerate four to five hours, but fruiting crops (tomatoes, squash, peppers) generally need six hours of full sunlight to grow strong and produce fruit.

When starting a garden, remember that we are in the northern hemisphere, and this means the sun dips to the south, especially in the winter. Objects therefore cast a shadow to the north, so pay attention to the position of southern tree lines, houses, and anything else that may block the sun. If you must choose, morning sun is better than afternoon sun, as afternoon sun can be very extreme in our area, especially in the summer.

Lastly, consider visibility! If you stick your garden in the very back corner of your yard, how often will you see it? The more visible it is in your daily life, the more likely you will notice easy-to-pull weeds, when your garden needs watering, what is ready to be harvested, and everything else that goes on in the garden.

Although wood is most popular, you can use materials such as concrete, bricks, or tiles to build a raised bed. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Materials

Now you have chosen a perfect garden location. What materials should you use to build your raised bed? Lumber is the most popular material. But you could use concrete blocks, bricks, tiles, or anything else that can support soil. You can make your beds as long as you like, but the important thing to remember is not to make the raised bed wider than four feet. This will allow you to reach all areas of your soil without stepping into the bed, which causes compaction. If you are working with kids, two or three feet wide is even better. You should make the height of your bed 10 to 12 inches, which will allow good drainage and enough space for your vegetable plants to develop strong roots.

When choosing lumber, you can go with untreated or treated wood. Within the last 15 years, wood preservatives considered unsuitable for raised-bed gardening have been phased out. There is well-documented research that has shown the newer products are considered safe for gardening. Although untreated wood typically will not last as long as treated, even treated wood will still begin to decompose after a few seasons. Either way, connect your wood with lag bolts, instead of nails, to hold the wood together tightly.

When filling a four ft. by eight ft. raised bed, you will need about 1 cubic yard of soil mix. Photo by Molly Jameson.

Soil

Now that you have your raised-bed structure built, what will you put in it? There are many landscape and nursery companies that can offer vegetable garden soil mixes for purchase in bulk. Typically, they will be about 50 percent compost (organic matter) and 50 percent top soil (nutrient-containing minerals). If you are filling a four foot by eight foot by 12 inch raised bed, you will need about one cubic yard of soil mix, which typically costs $30 to $60. This is about the volume of the back of a pick-up truck. If you do not have access to a truck, most companies will deliver in bulk for a $30 to $50 fee. This could be worth it if you are filling up multiple beds! Seasonally, you will then need to top off your raised bed as your soil will shrink as the organic materials decompose. But for this, you can buy bagged soil mixes or make your own compost.

The last step is filling your raised bed with vegetable plants! This could also be considered the first step… as you now must consider plant spacing, spring vs. fall vegetables, seeding into the garden vs. using transplants, trellising, pest control, harvesting…but we’ll save all that for future articles. Happy gardening!

by Ray Bodrey | Aug 19, 2016

Being a gardener in the panhandle has its advantages. We’re able to grow a tremendous variety of vegetables on a year-round basis. However, in this climate, plant diseases, insects and weeds can often thrive. Usually, chemical measures are applied to thwart these pests. Some panhandle gardeners are now searching for techniques regarding a more natural form of gardening, known as organic. With fall garden planting just ahead, this may be an option for conventional vegetable gardeners looking for a challenge.

Vegetable Garden at UF/IFAS Extension Wakulla County. Photo credit: Ray Bodrey UF/IFAS.

So, what is organic gardening? Well, that really depends on who you ask. A broad definition is gardening without the use of synthesized fertilizers and industrial pesticides. Fair warning, “organic” does not translate into easier physical gardening methods. Laborious weeding and amending of soil are big parts of this gardening philosophy. This begs the question, why give up these proven industrial nutrient and pest control practices? Answer: organic gardening enthusiasts are extremely health conscious with the belief that vigorous outdoor activity coupled with food free of industrial chemicals will lead to better nutrition and health.

As stated earlier, the main difference between conventional and organic gardening is the methods used in fertilization and pest control. In either gardening style, be sure to select a garden plot with well-drained soil, as this is key for any vegetable crop. Soil preparation is the most important step in the process. To have a successful organic operation, the garden will require abundant quantities of organic material, usually in the form of animal manures and compost or mixed organic fertilizer. These materials will ensure water and nutrient holding capacity. Organic matter also supports microbiological activity in the soil. This contributes additional nutrients for plant uptake. Organic fertilizers and conditioners work very slowly. The vegetable garden soil will need to be mixed and prepped at least three weeks ahead of planting.

Effective organic pest management begins with observing the correct planting times, selection of the proper plant variety and water scheduling. Selecting vegetable varieties with pest resistant characteristics should be considered. Crop rotation is also a must. Members of the same crop family should not be planted repeatedly in the same organic garden soil. Over watering can be an issue. Avoid soils from becoming too wet and water only during daylight hours.

For weed management, using hand tools to physically removing weeds is the only control method. As for insect management, planting native plants in the immediate landscape of the organic garden will help draw in beneficial insects that will feast on garden insect pests. The use of horticultural oil or neem oil is useful. However, please read the product label. Some brands of oils are not necessarily “organic”. Nematodes, which are microscopic worms that attack plant roots, are less likely an issue in organic gardens. High levels of organic matter in soil causes an inhospitable environment for nematodes. Organic disease management unfortunately offers little to no controls. Sanitation, planting resistant varieties and crop rotation are the only defense mechanisms. Sanitation refers to avoiding the introduction of potential diseased transplants. Disinfecting gardens tools will also help. Hydrogen peroxide, chlorine and household bleach are disinfecting chemicals allowed in organic gardening settings as these chemicals are used in organic production systems for sanitation. Staking and mulching are also ways to keep plants from diseases by avoiding contact with each other and the soil.

Organic gardening can be a challenge to manage, but better health and nutrition could be the reward. Please take the article recommendations into consideration when deciding on whether to plant an organic garden. For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, Organic Vegetable Gardening in Florida, by Danielle D. Treadwell, Sydney Park Brown, James Stephens, and Susan Webb.

by Mark Tancig | May 24, 2016

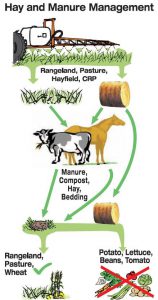

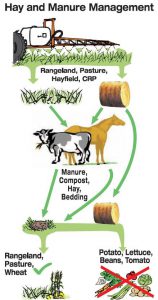

Humans have used animal manures to fertilize food crops for thousands of years. Manures are an organic source of plant nutrients and are often a waste byproduct that must be properly managed when raising animals. Today, many farmers and backyard gardeners continue to use animal manures to provide nutrition to their crops. However, a recent experience at our local extension office brought to our attention the need to know what else, besides nutrients, is in the manure used.

A local backyard gardener brought in samples of tomato plants that had strange new growth. She had purchased the tomato plants, along with other vegetable plants, from a local nursery. When she repotted the tomato plants into larger pots, she added horse manure from her own horses to the soil mix. She then noticed this strange growth on the tomatoes, but not in the other vegetable plants that were repotted without adding horse manure. Herbicide damage was one of the first potential causes we suggested, since the new growth was twisted and distorted, a common symptom of plants that have been sprayed by herbicides. The gardener was sure she had not sprayed any herbicides near these plants, or in the pasture where she keeps her horses.

Herbicide damaged tomato plants. Photo by: Mark Tancig

Photos of the tomato plants were shared with other NW District agents and an agriculture agent with livestock and hay producer experience had the probable answer – herbicide damage due to the horses being fed hay from a hayfield that was treated with a particular herbicide. Interestingly, this agent also had experience with these symptoms after their neighbor had similar issues using manure to fertilize the garden.

Herbicides with the active ingredients picloram or aminopyralid are able to cause this kind of unexpected damage to many gardeners’ crops. Herbicides containing these active ingredients are used in hayfields to control broadleaf weeds. These herbicides are especially effective at controlling hard to manage weeds such as thistle, nightshade, and nettle. They also provide long-lasting weed control. Unfortunately, the persistence of these ingredients extends into the hay, and also persists in the manure and urine of animals who eat hay from treated fields. These ingredients pass through the animal unchanged and remain active as an herbicide. Since many vegetable crops are broadleaf plants, the herbicide’s ingredients cause injury.

So what can a farmer or backyard gardener do to prevent this problem? When purchasing hay for livestock, ask the seller if they know whether the hayfield has been treated with herbicides that contain either picloram or aminopyralid. Most herbicides are known by their common names, rather than their chemical name. If they give you a common name or brand name, the active ingredient can be obtained by contacting your local extension office. If the seller can’t tell you, then, as a precaution, do not use the manure to fertilize broadleaf vegetable crops. The same question should be asked if purchasing hay for mulch as well. Composting the manure or hay does not break down the active ingredient, and may even concentrate it.

While we continue to use animal manures to fertilize our crops as our ancestors did, it’s important to remember that many of the tools and products we use today are much more advanced. These advanced products require that we stay informed of all precautions, use them responsibly, and, in this case, inform end users of any precautions. Remember to always read and follow the label and ask questions. And if a science-based answer is what you’re looking for, your local extension office is a good place to go!

Warning from herbicide label.

by Molly Jameson | Apr 7, 2016

Got Compost?

Please join UF/IFAS Leon County Agricultural and Horticultural Extension Agents for a hands-on composting workshop.

Extension Agents Mark Tancig and Molly Jameson will lead participants through:

-

An in-class presentation on composting science and research based composting methods

-

A hands-on demonstration on building and maintaining compost piles

-

Participants will help turn an existing compost pile and build a new pile

There are three chances to catch the workshop:

April 9, 10 am – 12 pm

April 19, 9 am – 11 am

April 25, 5:30 pm – 7:30 pm

General Admission: $10.00

Students: $5.00

Couples or Families: $15.00

The workshops will be held at the Leon County Extension Office, located at 615 Paul Russell Road, Tallahassee, Florida 32301.

by Beth Bolles | Dec 4, 2015

A visit to a nursery and homeowners will see so many new selections of plants for the landscape. Some of these plants are new plant developments and may include plants we could not previously grow in Florida’s heat and humidity. One new plant series is the Southgate® Rhododendrons.

Anyone from more northern areas of the South is very familiar with the rhododendrons that offer showy spring blooms. Those particular rhododendrons just don’t make it in our Florida climate.

The Southgate® series from Louisiana were developed to be more tolerant of our weather conditions. Homeowners must still consider plant placement very carefully since these plants have some specific requirements even in Florida. Plants will do best in shade or filtered shade, especially in the afternoon. They do like an acid soil amended with compost and areas that are well drained. Homeowners will need to supply water during the growing season to maintain a uniform soil moisture.

Rhododendron foliage with buds.

Consider trying one of these newer rhodendrons if your landscape has a suitable spot and you will definitely enjoy a bright spot of color come spring.

Special Note: If you have animals or children be cautious since all plant parts are toxic if ingested.