by Mark Tancig | Aug 1, 2017

Florida’s panhandle has received quite a bit of rain this summer. In the last three months, depending on the location, approximately 15 to 35 inches of rain have come down, with the western panhandle on the higher end of that range. In addition to the rain, we all know how hot it has been with heat index values in the triple digits. And who can forget the humidity?! Well, these weather conditions are just the right environmental factors for many types of fungi, some harmful to landscape plants, most not.

In the classification of living things, fungi are divided into their own Kingdom, separate from plants, animals, and bacteria. They are actually more closely related to animals than plants. They play an important role on the Earth by recycling nutrients through the breakdown of dead or dying organisms. Many are consumed as food by humans, others provide medicines, such as penicillin, while some (yeasts) provide what’s needed for bread and beer. However, there are fungi that also give gardeners and homeowners headaches. Plant diseases caused by various fungi go by the names rusts, smuts, or a variety of leaf, root, and stem rots. Fungal pathogens gardeners may be experiencing during this weather include:

- Gray leaf spot – This fungus can often show up in St. Augustine grass lawns. Signs of this fungus include gray spots on the leaf (very descriptive name!). This disease can cause thin areas of lawn and slow growth of the grass.

Gray leaf spot on St. Augustine grass. Credit: Phil Harmon/UF/IFAS.

- Take-all root rot – This fungus can attack all our warm-season turfgrasses, and may start as yellow leaf blades and develop into small to large areas of thin grass or bare patches. The roots and stolons of affected grasses will be short and black.

Signs of take all root rot. Credit: UF/IFAS.

Powdery mildew – This fungus can be found on many plants, from roses to cucumbers. It looks like white powder on the leaves and can lead to plant decline.

- Armillaria root rot – This fungus can infect a variety of landscape plants, including oaks, hickories, viburnums, and azaleas. Symptoms can include yellowing of leaves and branch dieback, usually in adjacent plants. Old hardwood stumps can harbor this fungus and lead to the infection of nearby ornamentals.

Because fungi are naturally abundant in the environment, the use of fungicides can temporarily suppress, but not eliminate, most fungal diseases. Therefore, fungicides are best used during favorable conditions for the particular pathogen, as a preventative tool.

Proper management practices – mowing height, fertilization, irrigation, etc. – that reduce plant stress go a long way in preventing fungal diseases. Remember that even the use of broadleaf specific herbicides can stress a lawn and exacerbate disease problems if done incorrectly. Since rain has been abundant, irrigation schedules should be adjusted to reduce leaf and soil moisture. Minimizing injury to the leaves, stems, and roots prevents stress and potential entry points for fungi on the move.

If you think your landscape plants are suffering from a fungal disease, contact your local Extension Office and/or visit the University of Florida’s EDIS website at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for more information.

by Matt Lollar | Jun 29, 2017

Algal leaf spot, also known as green scurf, is commonly found on thick-leaved, evergreen trees and shrubs such as magnolias and camellias. It is in the genus Cephaleuros and happens to be one of the only plant parasitic algae found in the United States. Although commonly found on magnolias and camellias, algal leaf spot has a host range of more than 200 species including Indian hawthorn, holly, and even guava in tropical climates. Algal leaf spot thrives in hot and humid conditions, so it can be found in the Florida Panhandle nearly year round and will be very prevalent after all the rain we’ve had lately.

Symptoms

Algal leaf spot is usually found on plant leaves, but it can also affect stems, branches, and fruit. The leaf spots are generally circular in shape with wavy or feathered edges and are raised from the leaf surface. The color of the spots ranges from light green to gray to brown. In the summer, the spots will become more pronounced and reddish, spore-producing structures will develop. In severe cases, leaves will yellow and drop from the plant.

Algal leaf spot on a camellia leaf. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

The algae can move to the stems and branches in more extreme cases. The algae can infect the stems and branches by entering through a small crack or crevice in the bark. The bark in that area cracks as a canker forms that eventually can girdle the branch, killing it.

Algal leaf spot on a sycamore branch. (Platanus occidentalis). Photo Credit: Florida Division of Plant Industry Archive, Bugwood.org.

Management

In most cases, algal leaf spot is only an aesthetic issue. If only a few leaves are affected, then they can just be removed by hand. \It is important that symptomatic leaves are discarded or composted offsite instead of being left in the mulched area around the trees or shrubs. If symptomatic leaves are left in the same general area then irrigation or rain water can splash the algal spores on healthy leaves and branches. Infected branches can also be removed and pruned.

Preventative measures are recommended for long-term management of algal leaf spot. Growing conditions can be improved by making sure that plants receive the recommended amount of sunlight, water, and fertilizer. Additionally, air circulation around affected plants can be increased by selectively pruning some branches and removing or thinning out nearby shrubs and trees. It is also important to avoid overhead irrigation whenever possible.

Fungicide application may be necessary in severe cases. Copper fungicides such as Southern Ag Liquid Copper Fungicide, Monterey Liqui-Cop Fungicide Concentrate, and Bonide Liquid Copper Fungicide are recommended. Copper may need to be sprayed every 2 weeks if wet conditions persist.

Algal leaf spot isn’t a major pathogen of shrubs and trees, but it can cause significant damage if left untreated. The first step to management is accurate identification of the problem. If you have any uncertainty, feel free to contact your local Extension Office and ask for the Master Gardener Help Desk or your County Horticulture Agent.

by Gary Knox | Jun 29, 2017

IPM for Shrubs in Southeastern US Nursery Production Volume II is the third book released by the Southern Nursery Integrated Pest Management Working Group (SNIPM) and includes chapters on hydrangea, loropetalum, holly, rhododendron (including azalea), Indian hawthorn, and weed management. Each chapter covers history, culture and management of the major species and cultivars in production, as well as arthropod pest management and disease management. Within the discussion of these topics, each chapter includes strategies for developing effective IPM programs for key pests and plant pathogens, including tables of fungicides and insecticides for use with these key organisms. While developed for nursery producers, this information also may be useful to landscapers, students, arborists and others.

This free book is downloadable as pdf chapters at

http://wiki.bugwood.org/IPM_Shrub_Book_II.

The first book, IPM of Select Deciduous Trees in Southeastern U.S. Nursery Production, was released in May 2012 and is available for free download as chapter .pdf files at http://wiki.bugwood.org/SNIPM and as an eBook from the iTunes Bookstore https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/ipm-for-select-deciduous-trees/id541182125?mt=11.

The second book, IPM for Shrubs in Southeastern US Nursery Production Volume I, was released in June 2014 and can also be downloaded as chapter .pdf files at http://wiki.bugwood.org/SNIPM or from the iTunes Bookstore at https://itunes.apple.com/us/book/ipm-for-shrubs-in-southeastern/id903114207?mt=11.

The SNIPM Working Group is a multi-disciplinary group of Extension professionals formed to more efficiently and effectively develop and deliver educational programming to the southern U.S. nursery and landscape industry.

by Mary Salinas | May 11, 2017

Citrus canker symptoms on twigs, leaves and fruit. Photo by Timothy Schubert, FDACS

In November 2013, citrus canker was found for the first time in the Florida panhandle in Gulf Breeze in southern Santa Rosa County. The Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) tested and confirmed the disease on grapefruit trees in a residential landscape. Since that time, citrus canker has been confirmed on citrus trees at 27 more locations in Gulf Breeze. To my knowledge it has not been found in any other location in the panhandle. Not yet.

Citrus canker lesions on leaves are raised, rough and visible on both sides of the leaf. Photo by Timothy Shubert, FDACS.

Citrus canker is a serious bacterial disease that only infects citrus trees. It will not infect any other plant species nor is it a threat to human health. This highly contagious disease has no cure as yet. Severely affected trees experience substantial leaf and premature fruit drop and serve as a source for infecting other citrus in the area. The disease spreads through wind, rain and transportation of infected plant material from other locations.

We do not know how the disease came to infect trees in our region. The disease could have been spread through infected fruit or trees brought here from areas where the disease is established, such as central or south Florida.

What should you do if you suspect your citrus is infected with this disease?

Citrus canker lesions can appear in the mines left by the citrus leafminer pest. Photo by Timothy Schubert, FDACS

- Look at Homeowner Fact Sheet: Citrus Canker for more information.

- Leave the tree in place in your yard and call the Division of Plant Industry at FDACS at 1-888-397-1517 for a free inspection and testing of your citrus trees.

- Consult your local Horticulture Extension Agent for more information and control/removal strategies.

- Proper removal of infected trees is recommended to prevent the spread of citrus canker but is not mandatory.

For more information please see:

Save Our Citrus Website

UF IFAS Gardening Solutions: Citrus

Citrus Culture in the Home Landscape

UF IFAS Extension Online Guide to Citrus Diseases

by Matt Lollar | Mar 20, 2017

A type III fairy ring. Photo Credit: Alex Bolques, Assistant Professor, Florida A&M University

Mushrooms often are grouped in a circle in your lawn. This is due to the circular release of spores from a central mushroom. “Fairy Ring” is a term used to describe this phenomenon. Fairy rings can be caused by multiple mushroom species such as Chlorophyllum spp., Marasmius spp., Lepiota spp., Lycoperdon spp., and other basidiomycete fungi.

Occurrence

Fairy rings most commonly invade your yard during the summer months, when the Florida panhandle receives the most rain. The mushrooms cause the development and spread of the rings by the release of spores. Spores produce more mushrooms and are similar to the seed produced by plants.

Fairy Ring “Types”

Fairy rings can be seen in three forms:

- Type I rings have a zone of dead grass just inside a zone of dark green grass. Weeds often invade the dead zone.

- Type II rings have only a band of dark green turf, with or without mushrooms present in the band.

- Type III rings do not exhibit a dead zone or a dark green zone, but a ring of mushrooms is present.

The size and fill of rings varies considerably. Rings are often 6 ft or more in diameter. The fill of a ring can range from a quarter circle to a semicircle or full circle.

Cultural Controls

The rings will disappear naturally, but it could take up to five years. Although it is possible to dig up the fairy ring sites, it is a good possibility the rings will return if the food source (buried, rotting wood or other organic matter) for the fungi is still present underground.

In some situations, the fungi coat the soil particles and make the soil hydrophobic (meaning it repels water), which will result in rings of dead grass. If the soil under this dead grass is dry but the soil under healthy grass next to it is wet, then it is necessary to aerate or break up the soil under the dead grass with a pitchfork or other cultivation tool.

Rings of dead turf due to fairy ring fungi. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension.

Chemical Controls

Effective fungicides include products containing the active ingredients azoxystrobin, flutolanil, metconazole, pyraclostrobin, and triticonazole.

Fungicides inhibit the fungus only. They do not eliminate the dark green or dead rings of turfgrass and do not solve the dry soil problem.

A homeowner’s guide to lawn fungicides can be found at the University of Florida/IFAS Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) website (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/document_pp154).

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2017

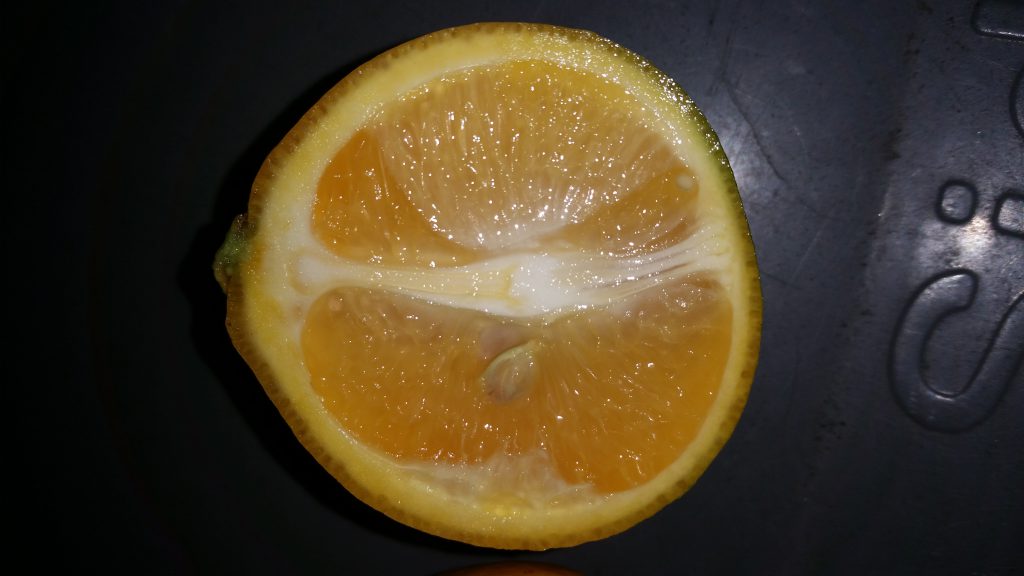

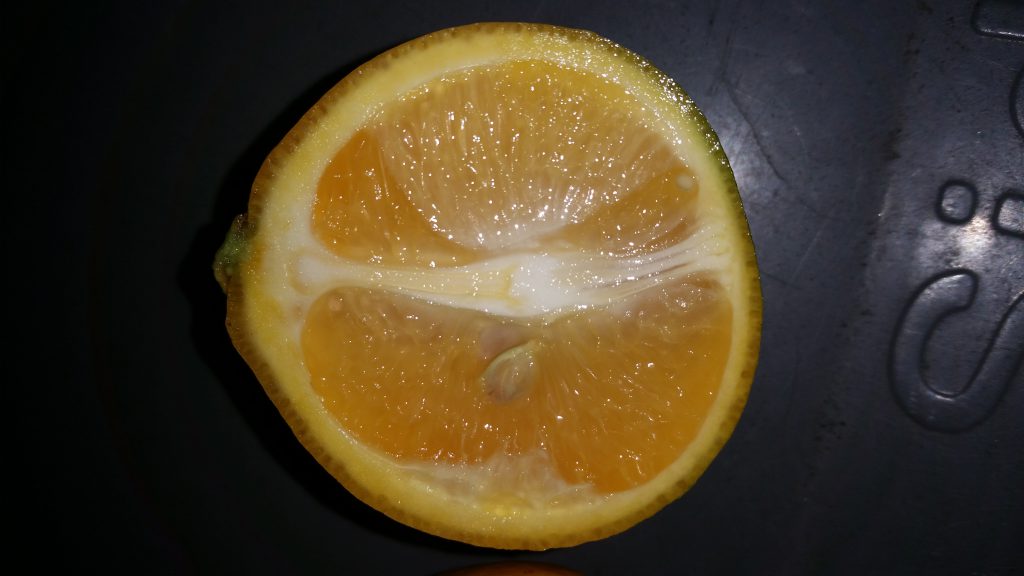

Small Fruit vs Normal

If we look at the big picture when it comes to invasive species, some of the smallest organisms on the planet should pop right into focus. A microscopic bacterium named Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, the cause of Citrus Greening (HLB), has devastated the citrus industry worldwide. This tiny creature lives and multiplies within the phloem tissue of susceptible plants. From the leaves to the roots, damage is caused by an interruption in the flow of food produced through photosynthesis. Infected trees show a significant reduction in root mass even before the canopy thins dramatically. The leaves eventually exhibit a blotchy, yellow mottle that usually looks different from the more symmetrical chlorotic pattern caused by soil nutrient deficiencies.

One of the primary vectors for the spread of HLB is an insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. These insects feed by sucking juices from the plant tissues and can then transfer bacteria from one tree to another. HLB has been spread through the use of infected bud wood during grafting operations also. One of the challenges with battling this invasive bacterium is that plants don’t generally show noticeable symptoms for perhaps 3 years or even longer. As you would guess, if the psyllids are present they will be spreading the disease during this time. Strategies to combat the impacts of this industry-crippling disease have involved spraying to reduce the psyllid population, actual tree removal and replacement with healthy trees, and cooperative efforts between growers in citrus producing areas. You can imagine that if you were trying to manage this issue and your neighbor grower was not, long-term effectiveness of your efforts would be much diminished. Production costs to fight citrus greening in Florida have increased by 107% over the past 10 years and 20% of the citrus producing land in the state has been abandoned for citrus.

Classic blotchy mottle in Leaves

Many scientists and citrus lovers had hopes at one time that the Florida Panhandle would be protected by our cooler climate, but HLB has now been confirmed in more than one location in backyard trees in Franklin County. The presence of an established population of psyllids has yet to be determined, as there is a possibility infected trees were brought in.

A team of plant pathologists, entomologists, and horticulturists at the University of Florida’s centers in Quincy and Lake Alfred and extension agents in the panhandle are now considering this new finding of HLB to help devise the most effective management strategies to combat this tiny invader in North Florida. With no silver-bullet-cure in sight, cooperative efforts by those affected are the best management practice for all concerned. Vigilance is also important. If you want to learn more about HLB and other invasive species contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

Asymmetrical Fruit

Typical nutrient deficiencies observed in leaf, on trees with heavy fruit load. Not related to Citrus Greening (HLB)

Article by: Erik Lovestrand, UF/IFAS Franklin County Extension Director/Florida Sea Grant Agent