by Roy Carter | Jun 10, 2014

Blueberry. Photo credit: Eric Zamora, UF IFAS.

Blueberries are native to Eastern North America. They are one of the few crop plants that originated here. The rabbiteye blueberry occurs mostly in certain river valleys in Northern Florida and Southeastern Georgia. The high bush blueberry is native to the eastern third of the United States and Southeastern Canada. Florida is rich in other native species. The woods and swamps of Florida are populated with at least eight wild blueberry species. No area of the state lacks wild blueberries, except where soil pH is above 6.0.

The two types of blueberries grown in Florida are Southern highbush and rabbiteye. The earliest ripening southern highbush varieties ripen about 4 to 6 weeks earlier than the earliest rabbiteye varieties grown at the same location.

Some rabbiteye varieties recommended for our area are: Alice blue, Beckyblue, Climax, Bonita, Brightwell, Chaucer and Tifblue. Some recommended Southern Highbush varieties are: Blue Crisp, Gulf Coast, Jewel, Sharpblue, Santa Fe, Star and Misty.

Blueberries need a fairly acid soil; a pH range of 4 to 5 is suggested. Blueberries grown on alkaline or deep sands will grow poorly. If you need to lower the soil pH before planting, mix in some acidic peat moss.

Blueberries have a shallow, fibrous root system. That means plants should be placed in the ground about an inch deeper than they were growing in the nursery. Rabbiteye blueberries grow poorly in soils with excessive drainage. But they won’t tolerate too much moisture for long periods of time either.

Blueberries are very sensitive to fertilizers. During the first growing season, no mineral fertilizer should be added at all. In the second season, apply about two ounces of an acidic fertilizer per plant. Blueberries can use the same fertilizer as camellias and azaleas, but be careful not to overdo it. Excessive amounts of fertilizer will kill the plants.

Before planting blueberries, you should cultivate the soil by plowing or roto tilling to a depth of at least six inches. Dig a hole large enough so that the roots won’t be crowded. Lightly pack the soil around the roots and water thoroughly. Keep in mind that newly set plants need a good water supply.

Bare-root bushes should be transplanted during the winter months; container grown bushes can be transplanted anytime. The first year after planting, the blossoms should be removed to help the bush grow more quickly.

Pruning is an important part of blueberry culture. It promotes the growth of strong wood, and rids the tree of weak twiggy growth. The strong wood growth is necessary for good fruit production.

Believe it or not, the worst pests of blueberries are birds. You need to protect your bushes with some kind of netting, or employ the old fashioned scarecrow to do the job. It you don’t protect your bushes, you can count on the birds getting to the fruit before you do.

Other than birds, rabbiteye blueberries have few pest or disease problems. Powdery mildew can occur on bushes that don’t get full sun, but this problem can be easily controlled with a sulfur spray. Bud mites, thrips, fruitworms, and defoliating insects can sometimes be a problem.

Weeds will compete with young blueberry bushes for nutrients and water, so keep the beds as free of weeds as possible. Mulches are good for controlling weed growth. If necessary, there are herbicides available.

For more information please see:

Blueberry Gardener’s Guide

by Eddie Powell | Jun 3, 2014

During this growing season monitor your plants and keep them healthy as a healthy plant will be able to better survive an invader attack.

Nematode populations can be reduced temporarily by soil solarization. It is a technique that uses the sun’s heat to kill the soil-borne pests. Adding organic matter to the soil will help reduce nematode populations as well. Nematodes are microscopic worms that attack vegetable roots and reduce growth and yield. The organic matter will also improve water holding capacity and increase nutrient content.

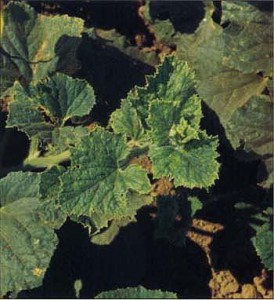

Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus

Credits: UF/IFAS

If you choose to use pesticides, please follow pesticide label directions carefully. Learn to properly identify garden pests and use chemicals only when a serious pest problem exists. If you have questions please call your UF/IFAS county extension office. We can provide helpful information about insect identification.

Organic gardeners can use certain products like BT(Dipel) to control pests. Please remember not every off-the-shelf pesticide can be used on every crop. So be sure the vegetable you want to treat is on the label before purchasing the product.

Follow label directions for measuring, mixing and pay attention to any pre-harvest interval warning. That is the time that must elapse between application of the pesticide and harvest. For example, broccoli sprayed with carbaryl (Sevin) should not be harvested for two weeks.

Spray the plant thoroughly, covering both the upper and lower leaf surfaces. Do not apply pesticides on windy days. Follow all safety precautions on the label, keep others and pets out of the area until sprays have dried. Apply insecticides late in the afternoon or in the early evening when bees and other pollinators are less active. Products like malathion, carbaryl and pyrethroids are especially harmful to bees.

To reduce spray burn, make sure the plants are not under moisture stress. Water if necessary and let leaves dry before spraying. Avoid using soaps and oils when the weather is very hot, because this can cause leaf burn.

Control slugs with products containing iron phosphate.

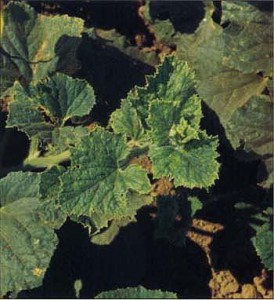

Cucumber Mosaic Virus

Credits: UF/IFAS

Many common diseases can be controlled with sprays like chlorothalonil, maneb, or mancozeb fungicide. Powdery mildews can be controlled with triadimefon, myclobutanil, sulfur, or horticultural oils. Rust can be controlled with sulfur, propiconazole, ortebuconazole. Sprays are generally more effective than dusts.

by Mary Salinas | Apr 15, 2014

Darrow’s Blueberry with spring blooms. Photo credit Mary Derrick UF IFAS.

A blueberry bush as a landscape shrub?

Yes! Darrow’s blueberry, Vaccinium darrowii, is closely related to the other blueberries you know and love, but this little gem of a shrub is highly ornamental and will fit in with any landscape scheme.

This compact shrub stays usually stays under three feet tall and wide, making it a perfect size for the home landscape. The small evergreen leaves emerge with a delightful pinkish tinge. In spring, pinkish white small flowers emerge and are followed by small but delicious blueberries. This blueberry will self-pollinate and set fruit, but studies have shown that there will be a sizable increase in fruit set if another variety of blueberry is close by for cross-pollination.

Darrow’s blueberry is a Florida native so it is perfectly adapted to our environmental conditions. Once established it has a moderate drought tolerance. Like other blueberries, it likes full sun, requires acidic soils with a pH between 4.0 and 5.5, and prefers the addition of organic matter into the planting bed if the soil is quite sandy. Pests are usually not a problem except for competition for the ripe fruit from wildlife.

If needed, there are several fertilizer options for blueberry; a 12-4-8 with 2% magnesium, a “blueberry special” formulation or a fertilizer formulated for camellias and azaleas. Whichever you use, apply the fertilizer lightly and widely spread around the plant– only about one ounce per plant every 2 months during the growing season April through October. Blueberries can be easily killed by too much fertilizer.

For more information, please see:

Blueberry Gardener’s Guide

Gardening Solutions: Blueberries

Florida Native Plant Society: Darrow’s Blueberry

Creating an Edible Landscape

by Julie McConnell | Apr 1, 2014

Container garden. Image: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

Living in a condo, apartment, or home with small yard does not mean you can’t garden at home. Whether you are interested in edible plants or ornamentals you can create a fit that is right for your space by using containers.

The first step in container gardening is the same as for traditional landscaping. First, asses your site to determine the cultural situation. Is it sunny or shady? Is water available from rainfall or from a nearby spigot? Will salt or wind be a factor? Are there height and width limitations? All of these need to be taken into consideration when you are planning to plant. These are elements that we have very little control over, so it is best to choose the right plants for the place you have.

Choose a container that will allow for adequate root growth and good drainage. If growing annuals, perennials, or small vegetables, a pot that is 12-18” deep should be sufficient. For shallow rooted or plants that like dry conditions you can go smaller. If plants grow tall make sure that the weight of the soil and pot is enough to keep it upright in gusty winds. It is not necessary to buy a container, you can reuse something as long as the water will drain and it is sturdy. Large containers may not need to be filled completely, but can be filled with a lightweight filler such as upside down nursery pots, water or soda bottles with lids, or packing peanuts. Choosing a light weight filler material makes the container easier to turn or relocate if needed and reduces the cost of potting soil.

Once you have determined site conditions, select the type of plants you would like to grow. When choosing edibles, the amount of sunlight available may be a limiting factor. Although some herbs and vegetables may benefit from a little bit of shade, they still need a bright location in order to produce well. If your site is very shady, consider shade loving ornamentals such as fern, hosta, and impatiens.

Understand the sunlight, water, and fertilizer needs of each plant. Group plants together that have similar requirements because they will receive the same care. Most herbs like a hot, dry situation and very little to no fertilizer. Grouping one of these herbs with a tomato plant that needs consistent watering and regular fertilizer will create a situation where one plant will perform poorly.

Container gardens require more care than plants in the ground because they dry out faster and may get no water from rainfall, if placed in a covered area. Consider using micro irrigation designed for containers or choose plants with low water needs such as the grasses and succulents.

To read more about container gardening read Container Gardening for Outdoor Spaces ENH1095.

The Foundation of the Gator Nation

An Equal Opportunity Institution

by Roy Carter | Mar 25, 2014

Image Credit UF IFAS Gardening solutions.

What does it mean to grow gardens organically? It depends upon who you talk to. The simple answer is that organic gardeners only use animal or plant-based fertilizers rather than synthetic. It also means use of natural pest control devoid of synthetically manufactured insecticides. In other words, using natural substances and beneficial insects to ward off pests instead of spraying with the backyard equivalent of Malathion. My information on organic vegetable gardening was provided by UF IFAS Extension Publication “Organic Vegetable Gardening” HS 1215.

Why garden organically? Since “USDA Certified Organic” does not apply to home gardening, why would any gardener give up all synthetic fertilizers? And why not use synthetic pesticides, when just one application could eliminate even the most devastating ravages of a crop insect or disease? Why work, so hard handling large quantities or organic soil amendments and manures when synthetic fertilizer of every description and purpose are so quickly available and easy to use?

Early organic gardeners did it to preserve a way of life that reduced pollution and environment decay, thus creating a more ecological society. Organic enthusiasts are extremely health-conscious, and hope that working vigorously outdoors and eating foods free from pesticides just might lead to better nutrition and health.

The biggest differences between organic and conventional gardening are in the area of fertilization and pest control. The organic gardener prefers organic materials and natural methods of dealing with insect problems and fertilizer requirements. The conventional gardener uses a combination of chemically prepared materials and scientific methods in approaching the vegetable garden.

Whichever method you choose, you need to select a plot of good, well-drained soil for planting vegetables. Also, it is important to choose vegetable varieties suited to Florida growing conditions.

Soil preparation is the most important step in organic gardening. Since organic fertilizers and soil conditioning materials work rather slowly, they need to be mixed into the soil at least three weeks ahead of planting time.

To have a successful organic garden, you need to use abundant quantities of organic material, usually in the form of animal manures, cover crops, compost or mixed organic fertilizer. These materials improve the tilth, condition, and structure of the soil. They help the soil hold water and nutrients better. In addition, organic matter supports micro-biological activity in the soil, and contributes major and minor plant nutrients. Another benefit is that as these organic matters decompose, they release acid which help to convert insoluble natural additives, such as ground rock, into forms plants can use.

by Mary Salinas | Mar 12, 2014

Delicious citrus! Photo by UF IFAS Thomas Wright.

All varieties of citrus – grapefruit, lemon, tangerine, kumquat and orange – are a vital part of our lives here in Florida. We love to grow citrus in our yards so that we can harvest the fruit fresh from the tree. On a wider scale, the citrus industry has a $9 billion annual impact on our economy providing over 76,000 jobs statewide.

But there are threats to our dooryard and commercial citrus from pests and disease. Only vigilance will help to combat the challenges so that we may continue to grow and enjoy our beloved citrus trees.

What can we do to protect our citrus?

- Learn about how to properly care for citrus and the pests and diseases that occur.

- Report any serious diseases like suspected citrus canker or citrus greening to the Division of Plant Industry by calling toll-free 1-888-397-1517.

- Purchase citrus trees only from registered nurseries – they may cost a little more but they have gone through an extensive process to remain disease and pest free. That will save you $$ in the long run!

- Don’t bring plants or fruit back into Florida – they may be harboring a pest!

- Citrus trees or fruit cannot move in or out of the State of Florida without a permit. This applies to homeowners as well as to the industry in order to protect our vital dooryard trees and citrus industry.

For more information please see:

Save Our Citrus Website

UF IFAS Gardening Solutions: Citrus

Citrus Culture in the Home Landscape

UF IFAS Extension Online Guide to Citrus Diseases

Your Florida Dooryard Citrus Guide – Common Pests, Disease and Disorders of Dooryard Citrus