by Matthew Orwat | Feb 14, 2017

Dooryard citrus enthusiasts may be uncertain about late winter management of Satsuma and other citrus trees. Several questions that have come in to the Extension Office recently include:

Dooryard citrus enthusiasts may be uncertain about late winter management of Satsuma and other citrus trees. Several questions that have come in to the Extension Office recently include:

- Should I prune my trees?

- Why are the leaves yellow?

- How soon should I fertilize?

The focus of this article is to provide some answers to these common questions.

Should I prune my trees?

This is a complicated question that is best answered with “it depends…” Pruning is not necessary for citrus, as it is in many temperate fruits, to have excellent production quality and quantity. Citrus trees perform excellently with minimal pruning. The only pruning necessary for most citrus is removing crossing or rubbing branches while shaping young trees, removing dead wood, and pruning out suckers from the root-stock. Homeowners may choose to prune citrus trees to keep them small, but this will reduce potential yield, since bigger trees produce more fruit.

Often, maturing Satsuma trees produce long vertical branches. It is tempting to prune these off, since they make the tree look unbalanced. To maximize yield, allow these branches to weep with the heavy load of fruit until they touch the ground. This allows increased surface area for the tree, since the low areas around the trunk are not bare. Additionally, weeds are suppressed since the low branches shade out weed growth. The ground under the trees remains bare, thus allowing heat from the soil to radiate up during cold weather events. The extra branches around the trunk offer added protection to the bud union as well. If smaller trees are desired for ease of harvest, ‘flying dragon’ root-stock offers dwarfing benefits, so that the mature scion cultivar size will only grow to 8-10 feet tall.

Heavy fruit loads were produced in many home gardens throughout Northwest Florida last year. When fruiting is heavy, citrus trees translocate nitrogen and other nutrients from older leaves to newer growth and fruit. Therefore, temporary yellowing may occur and last until trees resume growing in the spring. Remember, never fertilize after early September, since fertilizing this late in the year can reduce fruit quality and increase potential for cold injury. If a deficiency, as in the photo above persists through spring, consider a soil test, or consult a citrus production publication to determine if additional fertilizer should be added to your fertilizer program.

How soon should you fertilize?

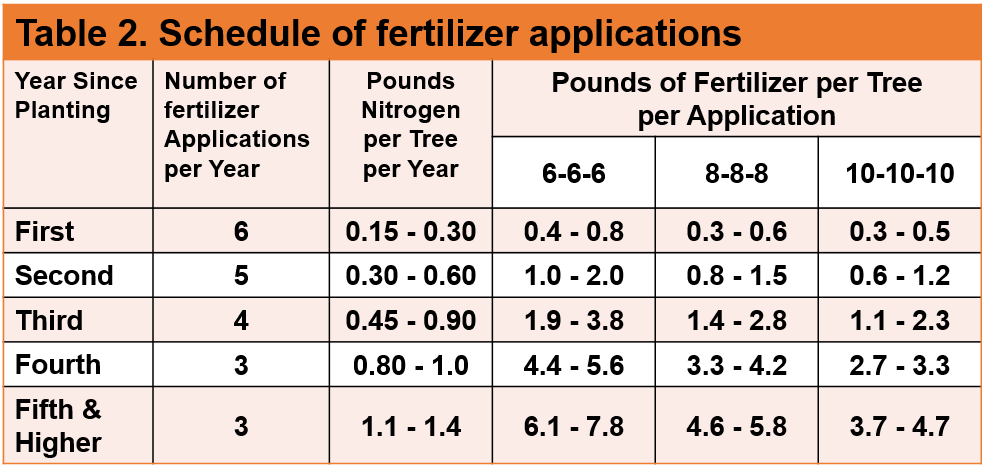

Although most Florida citrus publications recommend fertilizing citrus in February, they don’t take into account the potential for late frost in the Panhandle. Thus it makes more sense to wait until mid-March for the first fertilizer application in this region. Citrus trees don’t require a fertilizer with a high percentage of nitrogen, so it is best for fruit quality if an analysis of around 8-8-8 with micro-nutrients is used. Fertilizer should be applied in the drip-line of the tree, not around the trunk. The drip-line of a mature tree is generally considered to extend one foot from the trunk out to one foot from the edge of the furthest branch tip from the trunk. For fertilizer quantity recommendation see the chart below.

Through awareness of the unique managements techniques inherent to dooryard citrus production in the Panhandle, home gardeners are offered an opportunity to provide their friends and family with a substantial portion of their annual citrus !

For more information on this topic please use the following link to the UF/IFAS Publication:

by Larry Williams | Jan 26, 2017

Live oak with immature acorns. Photo credit: Wendy VanDyke Evans, Bugwood.org.

Do you have more acorns than you know what to do with? When oaks produce loads of acorns, it sometimes is called a “mast” year. Do you remember the oak tree pollen and all those catkins that fell from oaks earlier in spring?

Catkins are the male flowers in oaks. Some people refer to them as tassels or worms. The airborne pollen from these catkins were part of the reproductive process in fertilizing the female oak flowers that ultimately resulted in all of these acorns. Oaks produce separate male and female flowers on the same tree. Female flowers in oaks are very small. You’d have to look very close to see them. Many oaks did well in their reproductive efforts this spring. Acorns are oak seeds. This entire process is part of the cycle of life.

There are theories about mast years, wildlife’s use of these acorns and what gardeners can expect next year as a result of this year’s abundant acorn crop. Timing of mast years is still a mystery. Numerous theories exist ranging from weather to geography to the life cycles of predators.

The most likely reason for high production seems to be weather-related. When oak trees have favorable weather at the time of oak flowering and good growing conditions, the mast seems to be increased.

But mast years happen irregularly, making it difficult to understand what causes a mast year. Heavy acorn production can occur twice in a row or it might be separated by several years or more. There’s no good way to predict it.

Mast years are important to wildlife, as acorns are an important food for many animal species. In low crop years, birthrate for some wildlife species, such as squirrels, will decline the following year. This also may involve increased competition for food and survival rates. The recent crop means that more young are likely to be produced by animals that forage for acorns.

Wildlife play a big role in forest regeneration. When acorns drop out of oaks, many animals help distribute these seeds. Squirrels can bury hundreds of acorns. Some of these acorns germinate and grow to become the next generation of oak trees. Some will be eaten by birds, bears, deer, rodents, including squirrels, and other wildlife. Rodents are in turn eaten by carnivores and deer browsing shapes which kinds of plants become established and survive. All those acorns have far-reaching impact on wildlife and our forests.

So, try to keep this in mind as you are fussing with all those acorns in your lawn and landscape this season.

by Julie McConnell | Jan 17, 2017

Winter flowers and small leaves with serrated edges lead to identification as Camellia sasanqua. Photo: J_McConnell, UF/IFAS

A common diagnostic service offered at your local UF/IFAS Extension office is plant identification. Whether you need a persistent weed identified so you can implement a management program or you need to identify an ornamental plant and get care recommendations, we can help!

In the past, we were reliant on people to bring a sample to the office or schedule a site visit, neither of which is very practical in today’s busy world. With the recent widespread availability of digital photography, even the least technology savvy person can usually email photos themselves or they have a friend or family member who can assist.

If you need to send pictures to a volunteer or extension agent it’s important that you are able to capture the features that are key to proper identification. Here are some guidelines you can use to ensure you gather the information we need to help you.

Entire plant – seeing the size, shape, and growth habit (upright, trailing, vining, etc.) is a great place to begin. This will help us eliminate whole categories of plants and know where to start.

Stems/trunks – to many observers stems all look the same, but to someone familiar with plant anatomy telltale features such as raised lenticels, thorns, wings, or exfoliating bark can be very useful. Even if it doesn’t look unique to you, please be sure to send a picture of stems and the trunk.

Leaves – leaf color, size and shape is important, but also how the leaves are attached to the stem is a critical identification feature. There are many plants that have ½ inch long dark green leaves, but the way they are arranged, leaf margin (edges), and vein patterns are all used to confirm identification. Take several leaf photos including at least one with some type of item for scale such as a small ruler or a common object like a coin or ballpoint pen; this helps us determine size. Take a picture that shows how leaves are attached to stems – being able to see if leaves are in pairs, staggered, or whorled around a stem is also important. Flip the leaf over and take a picture of the underside, some plants have distinctive veins or hairs on the bottom surface that may not be visible in a picture taken from above.

Flowers – if flowers are present, include overall picture so the viewer can see where it is located within the plant canopy along with a picture close enough to show structure.

Fruit – fruit are also good identification pictures and these should accompany something for scale to help estimate size.

Any additional information you are able to provide can help – if the plant is not flowering but you remember that it has white, fragrant flowers in June, make sure to include that in your description.

Learning what plants you have in your landscape will help you use your time and resources more efficiently in caring for you yard. Contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office to find out who to send requests for plant id.

by Beth Bolles | Dec 22, 2016

A new tree or shrub is an investment for the future. When we pick an ornamental plant, we have the hope that it will survive for many years and offer seasons of beauty that enhance our landscape. Time is often spent picking a suitable spot, preparing the planting hole, and watering until establishment. We give it the best of care to make certain that our new plant becomes a more or less permanent feature.

With all of our tender love and care for new ornamentals, there is one important practice that we may neglect. Most homeowners purchase plants in containers and it is common to find root balls with circling roots. If any root ball problems are not addressed before installation, the life of your plant may be shorter than you want.

Ten years after installation, this plant was ultimately killed by girdling, circling roots. Photo by Warren Tate, Escambia County Master Gardener.

The best practice for woody ornamentals is to cut any roots that are circling the trunk or container. Homeowners may slice downward through the root ball around the entire plant. For shrubs, it is recommended to shave off “the entire outside periphery of the rootball” to eliminate circling roots. These practices allow the root system to grow outward into new soil and greatly reduce the possibility of girdling roots killing your plants years after establishment.

Circling roots are cut before installation. Photo by Beth Bolles, Escambia County Extension.

For more information on shrub establishment, visit the UF Publication Planting Shrubs in the Florida Landscape.

by Julie McConnell | Nov 22, 2016

Missing rose buds, pulled up pansies, and damaged tree trunks are all signs that something has been visiting your garden while you are away. But what could it be? Most gardeners are familiar with leaf spots caused by fungal diseases or minor feeding damage by insects, but to see half a shrub or an entire flower bed demolished overnight indicates a different type of pest.

Missing rose buds, pulled up pansies, and damaged tree trunks are all signs that something has been visiting your garden while you are away. But what could it be? Most gardeners are familiar with leaf spots caused by fungal diseases or minor feeding damage by insects, but to see half a shrub or an entire flower bed demolished overnight indicates a different type of pest.

There are several mammals that visit home landscapes and may cause damage, especially in times of drought when natural food sources are limited. Because we provide water for our landscapes, our plants tend to have lush new growth at times when plants in natural areas have slowed growth because of a lack of water or other stressors that managed gardens do not face. So, it’s no surprise that herbivores will be attracted to our landscape for a midnight snack.

It is important to determine what is causing damage so that you can employ protective tactics if possible. Some things to look for to try to figure out who the culprit is are footprints, dropping, feeding clues (bite marks, scrapes, etc.), or other distinctive damage. For more details about how to tell the difference between damage caused by multiple pests see How To Identify the Wildlife Species Responsible for Damage in Your Yard.

Once you have determined what is causing the damage you can try some different strategies to deter future feeding. Some plants may be impossible to protect, but before you spend your money and time check out these recommendations by wildlife specialists at the University of Florida in How to Use Deterrents to Stop Damage Caused by Nuisance Wildlife in Your Yard

by Beth Bolles | Nov 22, 2016

Leaf wilt may indicate more than just dry soil. Photo by Beth Bolles

Plants have specific ways of telling gardeners that there is a problem, but not all plant symptoms lead us directly to the cause. During drier conditions, we often use wilting leaves as an indicator that water is needed. This can be a reliable symptom that the soil is lacking moisture but it is not always the case. Wilting leaves and herbaceous branches actually tell us that there is not adequate water in the plant. It does not necessarily indicate lack of moisture in the soil.

There can be many reasons why water is not being absorbed by roots and moved to tissues in the plant. The obvious place to start is by checking soil moisture. If soil is powdery several inches deep around the plant, water is likely needed. However, if you ball the soil up in your hand and it holds together, there may be another reason for lack of water reaching the upper plant parts. The harder part is determining why the root system is not taking up water. Causes can be a rotted root system from too much water, a poorly developed root ball that has circling or kinked roots, and even problems in the soil such as compaction. Insects, diseases, and other pathogens can also injure root systems preventing the uptake of water.

Too much water can cause roots to decay, preventing the uptake of water. Photo by Beth Bolles

So before automatically grabbing the hose or turning on the sprinkler, do a little soil investigation to make sure that the plant wilt is really indicating lack of water in the soil. If you need help in your diagnosis, always contact your local Extension office.

Dooryard citrus enthusiasts may be uncertain about late winter management of Satsuma and other citrus trees. Several questions that have come in to the Extension Office recently include:

Dooryard citrus enthusiasts may be uncertain about late winter management of Satsuma and other citrus trees. Several questions that have come in to the Extension Office recently include: