by Blake Thaxton | Jul 21, 2017

Northwest Florida has experienced an enormous amount of rain this summer. The western panhandle has received over 29 inches of rain since the beginning of May according to the Florida Automated Weather Network station at the West Florida Research and Education Center in Jay, Florida. That is 44% of average annual rainfall in less than two months. All of this rain has probably thrown off the normal lawn mowing routine. It is hard to get out and mow the lawn when its pouring buckets or the lawn resembles a swamp. With all of this in mind, there are a couple of mowing pointers that would be useful to implement to address the out of control lawn growth and the challenges posed by not being able to stick to normal mowing schedule.

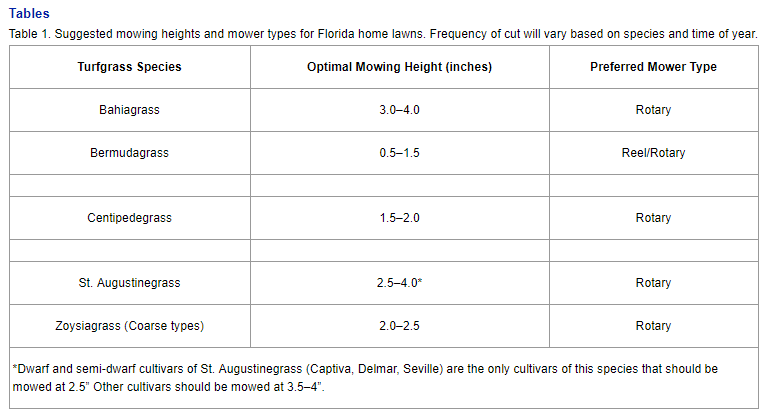

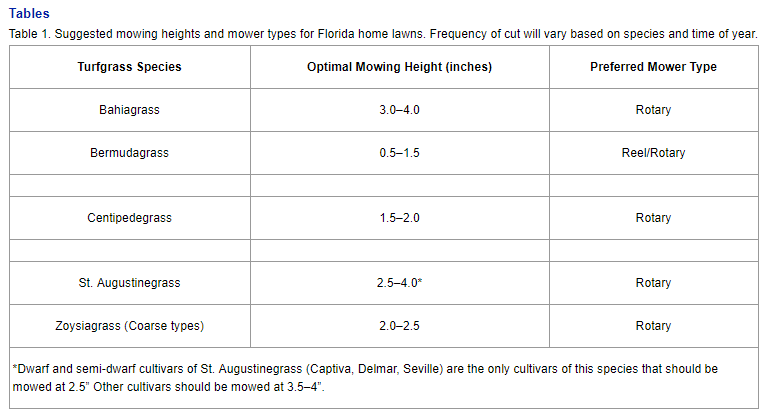

- Always attempt to mow at the IFAS recommended height for your species of turfgrass. The recommended heights are determined by how quickly the species grow in our climate. The chart below shows the best heights at which to mow your lawn. The fine textured zoysiagrasses are not listed but should be mowed at 0.5 to 1.5 inches. Check the lawn mowers mowing height by measuring the distance from the ground to the bottom of the mowing deck on a flat surface.

From Mowing Your Florida Lawn: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/LH/LH02800.pdf

- When you do get out to mow, never remove more than 1/3 of the leaf blade. If you cut to short you will “scalp” the turf and cause a brown look on the lawn. This can be damaging to the turf and allow for weeds to get established by exposing the soil to the sunlight. What is taking place more in northwest Florida is not mowing frequently enough and cutting off excess growth due to the rain. This also can cause scalping so it is very important to mow frequently enough to only remove 1/3 of the leaf blade.

A zoysia lawn that has been “scalped” after excess growth and infrequent mowing. (Photo Credit: Blake Thaxton)

Other practices such as keeping your mower blade sharp, mowing in different directions, and leaving clippings on the ground will help keep a healthy Florida lawn. Please see more information about mowing correctly in Florida in the University of Florida/IFAS Extension publication: Mowing Your Florida Lawn

by Matthew Orwat | Jun 16, 2017

Slime Mold Sporangia. Image Courtesy Matthew Orwat

Although black or white streaks are shocking when they appear on an otherwise healthy lawn, slime molds are rarely harmful.

Slime mold is actually caused by the reproductive structures of an array of different organisms, classified as plasmodia or Protista, which are regularly present in the soil. They are often mistaken for fungi. The different types are referred to as myxomycetes or dictyosteliomycetes. They usually appear on warm humid days in late spring or early summer after extended periods of rain. This extended period of heat and humidity, as is currently being experienced in the Florida Panhandle, initiates the perfect climate for slime mold development.

While regularly present in the soil, they usually make a visual appearance on warm humid days in late spring or early summer after extended periods of rain. This extended period of heat and humidity, currently being experienced in the Florida Panhandle, initiates the perfect climate for slime mold development.

As depicted in the picture, slime mold makes the lawn look like it was just spray-painted with black or grey paint. They can sometimes be pink, white, yellow or brown as well. The round fruiting bodies, called sporangia, carry the spores which will give rise to the next generation of the mold. After a few days the sporangia will shrivel up, release the spores and leave no noticeable trace on the lawn.

Closeup: Slime Mold in Centipedegrass. Image courtesy Matthew Orwat

Currently, no fungicide exists to control slime mold because chemical control is not necessary. An excellent method to speed up the dissipation of slime mold is to mow or rake the lawn lightly. This will disturb the spores and hasten their departure. Another effective removal method is to spray the lawn with a forceful stream of water. This process washes off the slime mold sporangia and restores the lawn to its former dark green beauty.

Excessive thatch accumulation also increases the probability of slime mold occurrence.

For more information consult your local county extension agent consult the UF / IFAS Slime Mold Fact Sheet, or read the Alabama Cooperative Extension publication Slime Mold on Home Lawns.

Slime Mold in Centipedegrass. Image Courtesy Matthew Orwat

by Larry Williams | Jun 10, 2017

Typical ground pearl damage to lawn. Photo Credit: Larry Williams

There are numerous reasons why maintaining a North Florida lawn is challenging and ultimately frustrating.

One such reason is ground pearls.

Ground pearls, small-scale insects that bother turfgrass roots, are soil dwelling pests that are not much of a problem in northern lawns. But they are quite the problem in North Florida lawns.

Most people, having never heard of ground pearls, may blame weeds, mole crickets and a multitude of other possible causes for their lawn’s demise. But in the last two to three years, this insect seems to have become more of a problem in many of our lawns, including mine.

Unfortunately, there is no effective chemical control for ground pearls in lawns.

Ground pearls feed on roots of bermudagrass, bahiagrass, St. Augustinegrass and zoysiagrass but prefer centipedegrass. They suck juices from the roots. Their feeding eventually causes areas of the lawn to thin and die out to bare ground, especially when the grass is under stress due to drought, nutritional deficiencies, etc.

Reddish adult female ground pearl & immature “pearl” stage. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Many times, the dying areas are somewhat circular or serpentine in pattern. Sometimes the circular areas coalesce, forming larger, irregular shaped dying areas. Weeds tend to invade infested areas.

The quote below, taken from a UF/IFAS Extension publication on this insect, provides some insight into their life cycle. “Clusters of pinkish-white eggs, covered in a white waxy sac, are laid in the soil from March to June. Tiny crawlers attach to roots and cover themselves with a hard, yellowish to purple, globular shell. These “pearls” range in size from a grain of sand to about 1/16 inch. They may occur as deep as 10 inches in the soil. The adult female is 1/16 inch long, pink in color, with well-developed forelegs and claws. Adult males are rare, tiny, gnat-like insects. One generation may last from 1 to 2 years.”

It is the immature stage (nymphs), which look somewhat like tiny pearls from which they get the “ground pearl” name. In this stage, they look like tiny shiny pearls once they are uncovered and exposed to sunlight. They are less than a BB in size. They overwinter in the “pearl” stage.

The ineffectiveness of insecticides is at least partly due to the ground pearl’s ability to avoid insecticides because of being protected in the soil and because of the prolonged protective “pearl” stage of its life cycle.

Since there are currently no biological or chemical controls that work, it’s recommended to minimize lawn stress and maintain proper fertilization and irrigation to help grass tolerate the damage.

Additional information on ground pearls is available at the following UF/IFAS Extension publication “Ground Pearls”.

by Daniel J. Leonard | May 18, 2017

If you’re like me, growing turfgrass is often more of a hassle than anything else. Regardless of the species you plant, none tolerates shade well and it can seem like there is a never-ending list of chores and expenses that accompany lawn grass: mowing (at least one a week during the summer), fertilizing, and constantly battling weeds, disease and bugs. Wouldn’t it be nice if there were an acceptable alternative, at least for the parts of the lawn that get a little less foot traffic or are shady? Turns out there is! Enter the wonderful world of perennial groundcovers!

Perennial groundcovers are just that, plants that are either evergreen or herbaceous (killed to the ground by frost, similar to turfgrass) and are aggressive enough to cover the ground quickly. Once established, these solid masses of stylish, easy to grow plants serve many of the same functions traditional turf lawns do without all the hassle: choke out weeds, provide pleasing aesthetics, reduce erosion and runoff, and provide a habitat for beneficial insects and wildlife.

The two most common turfgrass replacements found in Northwest Florida are Ornamental Perennial Peanut (Arachis glabra) and Asiatic Jasmine (Trachelospermum asiaticum); though a native species of Mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa) is gaining popularity also. All of these plants are outstanding groundcovers but each fills a specific niche in the landscape.

Perennial Peanut Lawn

Perennial Peanut is a beautiful, aggressive groundcover that spreads through underground rhizomes and possesses showy yellow flowers throughout the year; the show stops only in the coldest winters when the plant is burned back to the ground by frost. It thrives in sunny, well-drained soils, needs no supplemental irrigation once established and because it is a legume, requires little to no supplemental fertilizer. It even thrives in coastal areas that are subject to periodic salt spray! If Perennial Peanut ever begins to look a little unkempt, a quick mowing at 3-4” will enhance its appearance.

Asiatic Jasmine

Asiatic Jasmine is a superb, vining groundcover option for areas that receive partial to full shade, though it will tolerate full sun. This evergreen plant sports glossy dark green foliage and is extremely aggressive (lending itself to very rapid establishment). Though not as vigorous a climber as its more well-known cousin Confederate Jasmine (Trachelospermum jasminoides), Asiatic Jasmine will eventually begin to slowly climb trees and other structures once it is fully established; this habit is easily controlled with infrequent pruning. Do not look for flowers on this vining groundcover however, as it does not initiate the bloom cycle unless allowed to climb.

Sunshine Mimosa

For those that prefer an all-native landscape, Sunshine Mimosa (Mimosa strigillosa), also known as Sensitive Plant, is a fantastic groundcover option for full-sun situations. This herbaceous perennial is very striking in flower, sending up bright pink, fiber-optic like blooms about 6” above the foliage all summer long! Sunshine Mimosa, like Perennial Peanut, is a legume so fertility needs are very low. It is also exceptionally drought tolerant and thrives in the deepest sands. If there is a dry problem spot in your lawn that receives full sun, you can’t go wrong with this one!

As a rule, the method of establishing groundcovers as turfgrass replacements takes a bit longer than with laying sod, which allows for an “instant” lawn. With groundcovers, sprigging containerized plants is most common as this is how the majority of these species are grown in production nurseries. This process involves planting the containerized sprigs on a grid in the planting area no more than 12” apart. The sprigs may be planted closer together (8”-10”) if more rapid establishment is desired.

During the establishment phase, weed control is critical to ensure proper development of the groundcover. The first step to reduce competitive weeds is to clean the site thoroughly before planting with a non-selective herbicide such as Glyphosate. After planting, grassy weeds may be treated with one of the selective herbicides Fusilade, Poast, Select, or Prism. Unfortunately, there are not any chemical treatments for broadleaf weed control in ornamental groundcovers but these can be managed by mowing or hand pulling and will eventually be choked out by the groundcover.

If you are tired of the turfgrass life and want some relief, try an ornamental groundcover instead! They are low-maintenance, cost effective, and very attractive! Happy gardening and as always, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office for more information about this topic!

by Julie McConnell | Apr 7, 2017

It’s really tempting to buy a tree and plant it in the middle of your lawn or directly in front of your picture window, but instead take some time to choose the best spot first. Several considerations such as maintenance and mature size should be taken into account before the site is selected.

Mowing close to the trunk of this Pindo palm has caused repeated injury to the trunk. Photo: JMcConnell, UF/IFAS

Placing a tree in a lawn area without creating a bed can lead to maintenance issues for both the tree and the turfgrass. It is easy to simply cut out a small patch of turf the size of the rootball and install a tree, however, as the grass grows up towards the trunk over time maintaining that grass will become difficult. It is common to see mechanical injuries to tree trunks because weed eaters or mowers have chipped away at the bark when trying to cut the grass. Other potential problems are irrigation zones calibrated for turf delivering the wrong amount of water to trees and herbicides used on grass that may cause injury to trees.

Over time, as the tree canopy grows, it will create shade and any grass trying to grow in that area will thin and be more susceptible to disease and insect pressure. By creating a large ornamental bed for your tree, you will prevent some pitfalls associated with placing the tree in the lawn.

Another common mistake is planting a tree too close to a house or other structure. It can be difficult to imagine how large a tree will grow at maturity because it is not a quick process. Trees placed close to houses may grow into eaves and shed leaves onto roofs and into gutters. This adds to maintenance and can provide mosquito breeding grounds. Also, some tree roots may interfere with walkways or septic systems and should be sited far enough away to avoid these issues.

These Japanese Maples are planted in a bed separate from the lawn making care for both plant types easier. Photo: JMcConnell, UF/IFAS

Be sure to research any tree you plan to install to find out ideal growing conditions and mature size. If you plan ahead and use good maintenance practices, a tree can become an valuable part of your home landscape to be enjoyed for years to come.

by Matt Lollar | Mar 20, 2017

A type III fairy ring. Photo Credit: Alex Bolques, Assistant Professor, Florida A&M University

Mushrooms often are grouped in a circle in your lawn. This is due to the circular release of spores from a central mushroom. “Fairy Ring” is a term used to describe this phenomenon. Fairy rings can be caused by multiple mushroom species such as Chlorophyllum spp., Marasmius spp., Lepiota spp., Lycoperdon spp., and other basidiomycete fungi.

Occurrence

Fairy rings most commonly invade your yard during the summer months, when the Florida panhandle receives the most rain. The mushrooms cause the development and spread of the rings by the release of spores. Spores produce more mushrooms and are similar to the seed produced by plants.

Fairy Ring “Types”

Fairy rings can be seen in three forms:

- Type I rings have a zone of dead grass just inside a zone of dark green grass. Weeds often invade the dead zone.

- Type II rings have only a band of dark green turf, with or without mushrooms present in the band.

- Type III rings do not exhibit a dead zone or a dark green zone, but a ring of mushrooms is present.

The size and fill of rings varies considerably. Rings are often 6 ft or more in diameter. The fill of a ring can range from a quarter circle to a semicircle or full circle.

Cultural Controls

The rings will disappear naturally, but it could take up to five years. Although it is possible to dig up the fairy ring sites, it is a good possibility the rings will return if the food source (buried, rotting wood or other organic matter) for the fungi is still present underground.

In some situations, the fungi coat the soil particles and make the soil hydrophobic (meaning it repels water), which will result in rings of dead grass. If the soil under this dead grass is dry but the soil under healthy grass next to it is wet, then it is necessary to aerate or break up the soil under the dead grass with a pitchfork or other cultivation tool.

Rings of dead turf due to fairy ring fungi. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension.

Chemical Controls

Effective fungicides include products containing the active ingredients azoxystrobin, flutolanil, metconazole, pyraclostrobin, and triticonazole.

Fungicides inhibit the fungus only. They do not eliminate the dark green or dead rings of turfgrass and do not solve the dry soil problem.

A homeowner’s guide to lawn fungicides can be found at the University of Florida/IFAS Extension Electronic Data Information Source (EDIS) website (http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/document_pp154).