by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 21, 2018

After a devastating windstorm, as we just experienced in the Panhandle with Hurricane Michael, people have a tendency to become unenamored with landscape trees. It is easy to see why when homes are halved by massive, broken pine trees; pecan trunks have split and splayed, covering entire lawns; wide-spreading elms were entirely uprooted, leaving a crater in the yard. However, in these times, I would caution you not to rush to judgement, cut and remove all trees from your landscape. On the contrary, I’d encourage you, once the cleanup is over and damaged trees rehabilitated or disposed of, to get out and replant your landscape with quality, wind-resistant trees.

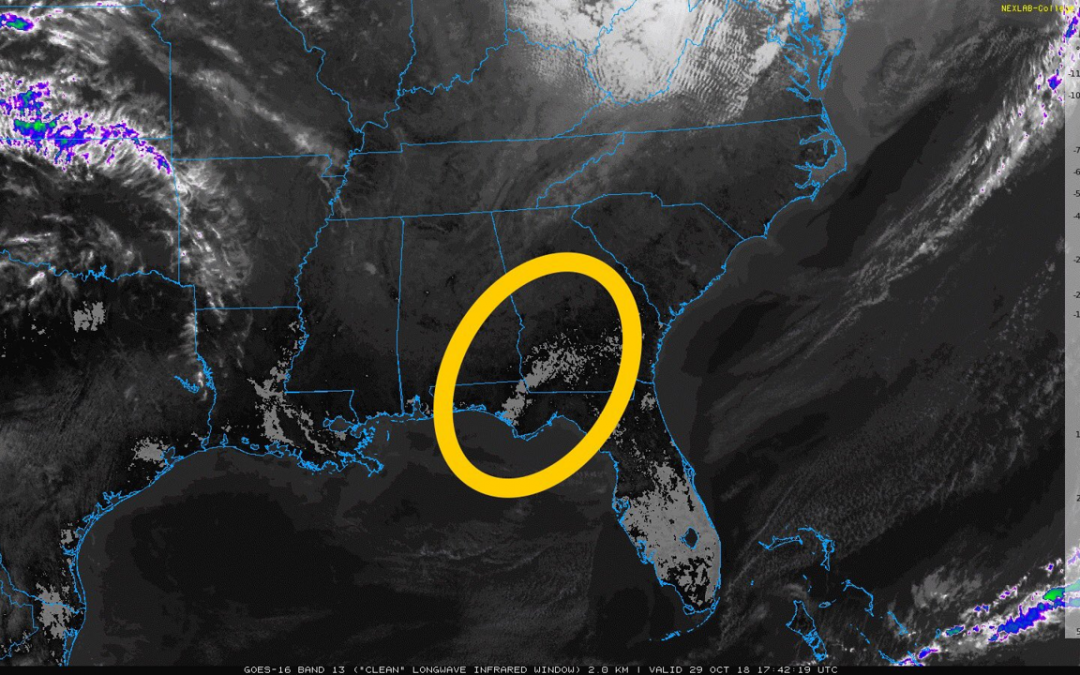

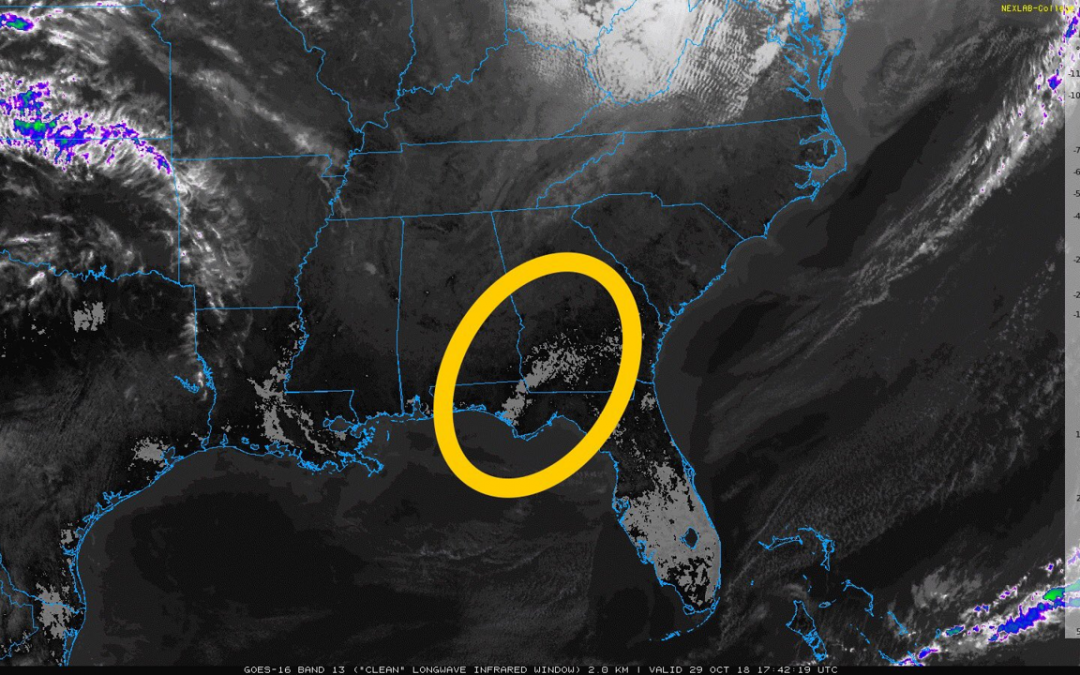

First, it’s helpful to take a step back and remember why we plant and enjoy trees and the important role they play in our lives. Beyond the commercial aspect of farmed timber, there are many reasons to be judicious with the chainsaw in the landscape and to plant anew where seemingly sturdy trees once stood. For example, trees provide enormous service to homes and landscapes, from massive cooling effects to aesthetic appeal. Take this thermal satellite image of Hurricane Michael’s path that simultaneously shows the devastation of a major hurricane and the role trees play in the environment.

Lightly shaded area showing higher ground temperatures from loss of vegetation.

In the lighter colored areas where the wind was strongest and catastrophic tree damage occurred, the ground temperatures are much higher than the unaffected areas. Lack of plant life is entirely to blame. Plants, especially trees, provide enormous shading effects on the ground that moderate ground temperatures and the process of transpiration releases water vapor, cooling the ambient air. Trees also lend natural beauty to neighborhood settings. There is a reason people termed the hardest hit areas by Michael “hellscapes”, “warzones”, etc. Those descriptions imply a lack of vegetation due to harsh conditions. In this respect, trees soften the landscape with their foliage colors and textures, create architecture with their height and shape, and screen people from noise, unpleasant sights and harsh heat.

Though all trees give us the benefits outlined above, research conducted by the University of Florida over a span of ten major hurricanes, from Andrew to Katrina, shows that some trees are far more resistant to wind than others and fare much better in hurricanes. In North Florida, the trees that most consistently survived hurricanes with the least amount of structural damage were Live Oaks, Cypresses, Crape Myrtle, American Holly, Southern Magnolia, Red Maple, Black Gum, Sycamore, Cabbage Palm and a smattering of small landscape trees like Dogwood, Fringe Tree, Persimmons, and Vitex. If one thinks about these trees’ growth habits, broad resistance to disease/decay, and native range, that they are storm survivors comes as no surprise. Consider Live Oak. This species originated along the coastal plain of the Southeastern United States and have endured hurricanes here for several millennia. Possessing unusually strong wood, they have also developed the ability to shed the majority of their leaves at the onset of storms. This defense mechanism leaves a bare appearance in the aftermath but allows the tree to mostly avoid the “umbrella” effect other wide crowned trees experience during storms and retain the ability to bounce back quickly. Consider another resistant species, Bald Cypress. In addition to having a strong, straight trunk and dense root system, the leaves of Bald Cypress are fine and featherlike. This leaf structure prevents wind from catching in the crown. Each of the other listed species possess similar unique features that allow them to survive hurricanes and recover much more quickly than other, less adapted species.

Laurel Oak split from weak branching structure.

However, many widely grown native trees and exotic species simply do not hold up well in tropical cyclones and other wind events. Pine species, despite being native to the Coastal South, are very susceptible to storm damage. The combination of high winds and beating rains loosens the soil around roots, adds tremendous water weight to the crown high off the ground, and puts the long, slender trunks under immense pressure. That combination proves deadly during a major hurricane as trees either uproot or break at weak points along the trunk. In addition to pines, other widely grown native species (such as Pecan, Laurel Oak and Water Oak) and exotic species (such as Chinese Elm) perform poorly in storms. Just as the trees that survive storms well possess similar features, so do these poor performers. We’ve already mentioned why pines and hurricanes don’t mix well. Pecan, Laurel Oak, and Water Oak tend to have weak branch angles and break up structurally in wind events. The broad spreading, heavy canopy of trees like Chinese Elm cause them to uproot and topple over. It would be advisable when replanting the landscape, to steer clear of these species or at least site them a good distance from important structures.

This piece is not a warning to condemn planting trees in the landscape; rather it is a template to guide you when selecting trees to replant. Many of our deepest memories involve trees, whether you first climbed one in your grandparent’s yard, fished under one around a farm pond, or carved your initials into one in the forest. Don’t become frustrated after a once in a lifetime storm and refuse to replant your landscape or your forest and deprive your children of those experiences. As sage investor Warren Buffett once wisely said, “Someone is sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

For these and other recommendations about how to “hurricane-proof” your landscape, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. Plant a tree today.

by Matt Lollar | Nov 8, 2018

A planted tree with water retention berm. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Often, Extension agents are tasked with evaluation of unhealthy plants in the landscape. They diagnose all sorts of plant problems including those caused by disease infection, insect infiltration, or improper culture.

When evaluating trees, one problem that often comes to the surface is improper tree installation. Although poorly installed trees may survive for 10 or 15 years after planting, they rarely thrive and often experience a slow death.

Fall is an excellent time to plant a tree in Florida. A couple of weeks ago beautiful Nuttal Oak was planted at Bagdad Mill Site Park in Santa Rosa County, FL. Here are 11 easy steps to follow for proper tree installation:

- Look around and up for wire, light poles, and buildings that may interfere with growth;

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible;

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk;

- Slide the tree carefully into the planting hole;

- Position the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface;

- Straighten the tree in the hole;

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball;

- Slice a shovel down in to the back fill;

- Cover the exposed sides of the root ball with mulch and create water retention berm;

- Stake the tree if necessary;

- Come back to remove hardware.

Digging a properly sized hole for planting a tree. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Removing synthetic material from the root ball. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

Straightening a tree and adjusting planting height. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida – Santa Rosa County

For more detailed information on planting trees and shrubs visit this UF/IFAS Website – “Steps to Planting a Tree”.

For more information Nuttall Oaks visit this University of Arkansas Website.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 2, 2018

Each fall, nature puts on a brilliant show of color throughout the United States. As the temperatures drop, autumn encourages the “leaf peepers” to hit the road in search of the red-, yellow- and orange-colored leaves of the northern deciduous trees. In Northwest Florida the color of autumn isn’t just from trees. The reds, purples, yellow and white blooms and berries that appear on

Each fall, nature puts on a brilliant show of color throughout the United States. As the temperatures drop, autumn encourages the “leaf peepers” to hit the road in search of the red-, yellow- and orange-colored leaves of the northern deciduous trees. In Northwest Florida the color of autumn isn’t just from trees. The reds, purples, yellow and white blooms and berries that appear on

Monarch butterfly on dense blazing star (Liatris spicata var. spicata).

Beverly Turner, Jackson Minnesota, Bugwood.org

many native plants add spectacular color to the landscape. American Beautyberry, Callicarpa americana, is loaded with royal-colored fruit that will persist all winter long. Whispy pinkish-cream colored seedheads look like mist atop Purple Lovegrass, Eragrostis spectabilis and Muhlygrass, Muhlenbergia capillaris. The Monarchs and other butterfly species flock to the creamy white “fluff” that covers Saltbrush, Baccharis halimifolia. But, yellow is by far the dominant fall flower color. With all the Goldenrod, Solidago spp., Narrowleaf Sunflower, Helianthus angustifolius and Tickseed, Coreopsis spp., the roadsides are golden. When driving the roads it’s nearly impossible to not see the bright yellows in the ditches and along the wood’s edge. Golden Asters (Chrysopsis spp.), Tickseeds (Coreopsis spp.), Silkgrasses (Pityopsis spp.), Sunflowers (Helianthus spp.) and Goldenrods (Solidago spp.) are displaying their petals of gold at every turn. These wildflowers are all members of the Aster family, one of the largest plant families in the world. For most, envisioning an Aster means a flower that looks like a daisy. While many are daisy-like in structure, others lack the petals and appear more like cascading sprays. So if you are one of the many “hitting the road in search of fall color”, head to open areas. For wildflowers, that means rural locations with limited homes and businesses. Forested areas and non-grazed pastures typically have showy displays, especially when a spring burn was performed earlier in the year. Peeking out from the woods edge are the small red trumpet-shaped blooms of Red Basil, Calamintha coccinea and tall purple spikes of Gayfeather, Liatris spp.

Visit the Florida Wildflower Foundation website, www.flawildflowers.org/bloom.php, to see both what’s in bloom and the locations of the state’s prime viewing areas. These are all native wildflowers that can be obtained through seed companies. Many are also available as potted plants at the local nurseries. Read the name carefully though. There are cultivated varieties that may appear or perform differently than those that naturally occur in Northwest Florida. For more information on Common Native Wildflowers of North Florida go to http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/ep061

by Larry Williams | Oct 2, 2018

American Beautyberry Fruit.

Photo credit: Larry Williams

American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) puts on quite a show during late summer and fall with its bright purple fruit. I have some of these plants in my landscape and they are beginning to show color now with their profusion of berry-like fruit found along the thin branches, resulting in the plant taking on a weeping habit.

Each fruit is only about 1/3 inch in diameter but collectively form roundish clusters that encircle the stems. The berries are particularly showy in September and October. They remain on the plant, even after its leaves have dropped, into early winter if not eaten by birds and other wildlife.

Many species of birds will eat beautyberry fruit including robins, cardinals, mockingbirds, brown thrashers, finches and towhees. Birds are a major method of seed dispersal for this plant.

One of my neighbors noticed my plants a number of years ago and commented, “I had never thought about using this plant in a landscape.” He grew up in Northwest Florida and had always been used to seeing American beautyberry plants growing in the wild as they are native. The plant is not well suited for manicured, formal landscapes but can be useful in a naturalized garden.

Even though I consider the showy fruit its best attribute, the small, lavender flowers tightly bunched together along the stems during June to August are attractive, as well.

American beautyberry is a deciduous shrub without much ornamental value during the winter. But during the growing season, its somewhat course, fuzzy, light-green leaves look good in a setting with other darker-leaved shrubs.

It grows well in part shade/part sun as an understory plant beneath larger trees such as pines and oaks.

Be sure to allow enough room for this sprawling shrub to develop into its mature size of three to eight feet in height with an equal spread.

It may also be used as an informal screen or even as a specimen plant. But avoid using it where it will require regular shearing as the flowers and fruit are produced on new growth.

Thinning out old or low-growing branches is a better method of pruning this plant. American beautyberry may self-seed but I have not seen this to be a bothersome problem.

America beautyberry is somewhat available in the nursery trade and is fairly easy to propagate from stem cuttings. It can be propagated from seeds, as well. In addition to the purple fruiting types, look for cultivars such as ‘Russell Montgomery’ that produce white fruit. There are also other nonnative species of Callicarpa worth looking at, such as C. dichotoma and C. japonica.

by Mary Salinas | Aug 29, 2018

Versatile, easy-care, beautiful, native – what’s not to love about muhly grass?

Muhly grass is a hardy landscape choice with dramatic fall blooms. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

How is it versatile? It makes a perfect border along a fence or structure. Plant it in a single or double row depending on available space. Use a single plant as a specimen in a smaller landscape. Muhly grass can also be planted in mass to serve as groundcover in a larger landscape.

What makes it easy-care? Since it only grows into a 3-foot-tall mound, there is no need to continually prune it as you would have to do for many landscape shrubs that serve a similar function. Plant muhly grass in areas where you only want to have plants grow to a 3-foot height, such as under windows or along a short fence. This clumping grass can be pruned in late winter to remove dead leaf blades, but it is not necessary. There are few pest and disease issues and its’ fertility needs are low. This tough plant can handle both drought and inundation with water. Perfect for a rain garden! Flowering is best in full sun, but it can take part sun as well.

What’s so beautiful about a grass? In the fall, abundant pink to pinkish/purple blooms cover the canopy of the grass and add color to the fall landscape. The wispy blooms move with the breezes and add interest with their movement. The new cultivar ‘Fast Forward’ blooms as early as August and into the winter. If pink is not your color, there is a form with white blooms known as ‘White Cloud’.

Consider adding some muhly grass to your landscape. You will love it as I do.

by Julie McConnell | Aug 29, 2018

In 2016, I wrote an article for Gardening in the Panhandle called “Attract Pollinators with Dotted Horsemint” introducing readers to this tough native plant that supports native pollinators. If you have flowers in your garden, you probably have pollinators and a whole lot of other insects but if you want a plant that lets you observe a really diverse palate of bugs dotted horsemint Monarda punctata.

When I find I have some downtime at home I have a habit of wandering the yard looking for interesting insects. Admittedly, I usually have my phone in hand hoping to get a great photo or video of my arthropod visitors, but it is a productive task, too. As strange as it may sound, I can count this hobby as part of my integrated pest management landscape maintenance strategy – scouting!

My favorite plant to visit on my scouting run is normally not afflicted with pests, but it hosts so many different insects it always gets a stop on my rounds. When dotted horsemint is in full flower it is visited by a lot more than pollinators. I’ve recorded daily visits from assassin bugs, ants, beetles, flies, dragonflies, spiders, thread-waisted wasps, honey bees, butterflies, and moths.

Here’s a photo album of frequent visitors to my dotted horsemint from this summer – enjoy!