by Julie McConnell | Oct 31, 2024

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.

Camellia japonica

Also known as Japanese Camellia, C. japonica thrive in partial sun to full shade. Direct morning sun with some shelter from the sun in the hottest part of the day is a good compromise. Too much shade can reduce flowering, so aim for at least partial sun.

Most Japanese Camellias bloom from January to March, but some may start earlier in the season. Flower shapes include single, semi-double, anemone, peony, and formal double. Flower colors are white, pink, red, and sometimes a combination of multiple colors! Camellia japonica mature at 10-15’ tall and wide but may get as big as 25 feet. This makes them ideal to create privacy in the garden or have the lower limbs trimmed into a tree-form.

Camellia sasanqua

Sasanqua camellias also prefer part sun but can also thrive in full sun once established. Leaves and flowers are typically smaller than C. japonica which is an easy way to differentiate. Although most have upright habits and can grow 10-15’ tall as well, there are a few cultivars such as ‘Shishi Gashira’, ‘Bonanza’, and ‘Mine-no-yuki’ that have more horizontal branching making them good options for foundation plantings. Sasanqua camellia are usually in full bloom in the fall, but may bloom as late as January. Flower shapes are similar to C. japonicas, but many varieties have more open flowers with exposed stamens that are beneficial to pollinators.

by Lauren Goldsby | Oct 17, 2024

Orange chrysanthemum flowers in bloom. Photo credit: Lauren Goldsby

It feels like everywhere you turn, chrysanthemums are the star of the show right now. These hardy blooms offer a bounty of fall color to your front porch and seasonal decorations, making them a go-to favorite for sprucing up your space.

We typically see mums offered at garden centers and supermarkets this time of year, with their fall hues of yellow, burgundy, orange, and purple. But here’s the secret: as a perennial plant, mums can do so much more than just serve as a short-lived decoration. With the right care, they can become a permanent part of your landscape, blooming year after year and keeping that fall feeling alive long after the season ends.

To enjoy your mums for more than a few weeks follow these tips!

It’s ok to be picky

When shopping, look for mums with buds that have just started to open and show a hint of color. This ensures you’re choosing the color you want while also increasing the time you can enjoy the flowers at home.

Flowers just starting to open on a chrysanthemum. Photo credit: Lauren Goldsby

Water wisely

While temperatures are cooling down, don’t let that fool you into thinking your mums don’t need regular watering. The middle of the day can still bring heat and producing flowers is energy intensive for the plant. Be sure to check the top inch of soil regularly. If it feels dry, it’s time to water! Mums in full sun may require daily watering but try to avoid getting water on the leaves—this helps prevent pathogens from spreading.

Make room for more bloom

Once flowers have bloomed and begin to fade, it’s important to remove them—this is called deadheading. By trimming away the spent blooms, you’re helping the plant conserve energy and encouraging more new buds to grow. Plus, it keeps the plant looking neat and tidy!

Don’t toss them

When it’s time to make space for poinsettias, simply move your mums to a sunny spot in the yard. Mums can be kept in their containers or planted in the ground. If you’re planting them in the ground and have sandy soil, amend with compost. In late spring, when flowering has ended, prune off the top 2 inches of growth. You can propagate mums by taking vegetative cuttings or dividing the plants.

If you love the look of mums, check out these other plants in the Asteraceae family, many of which are native to Florida. https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/plants/ornamentals/asters/

by Mark Tancig | Oct 4, 2024

One of the best parts about working at the Extension Office is all we learn from the questions we field from curious citizens. I recently had a question about ozone sensitivity in a plant and if that meant it shouldn’t be planted near a street. A little research had me learning all about this interesting topic and finding out that there are even ozone gardens being planted to monitor for air quality.

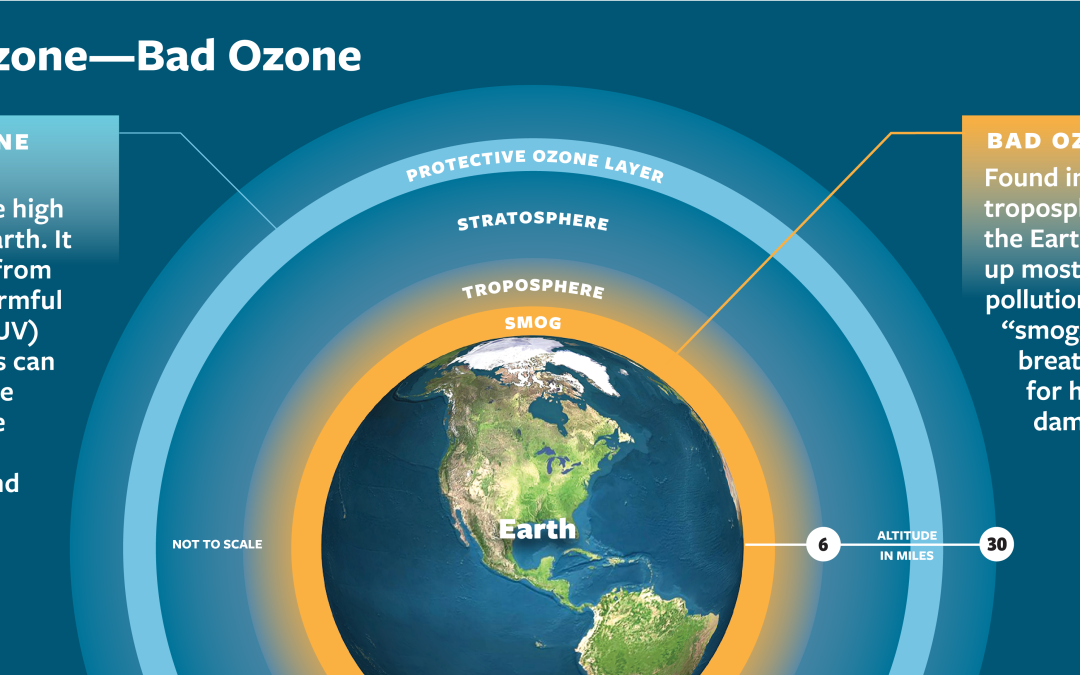

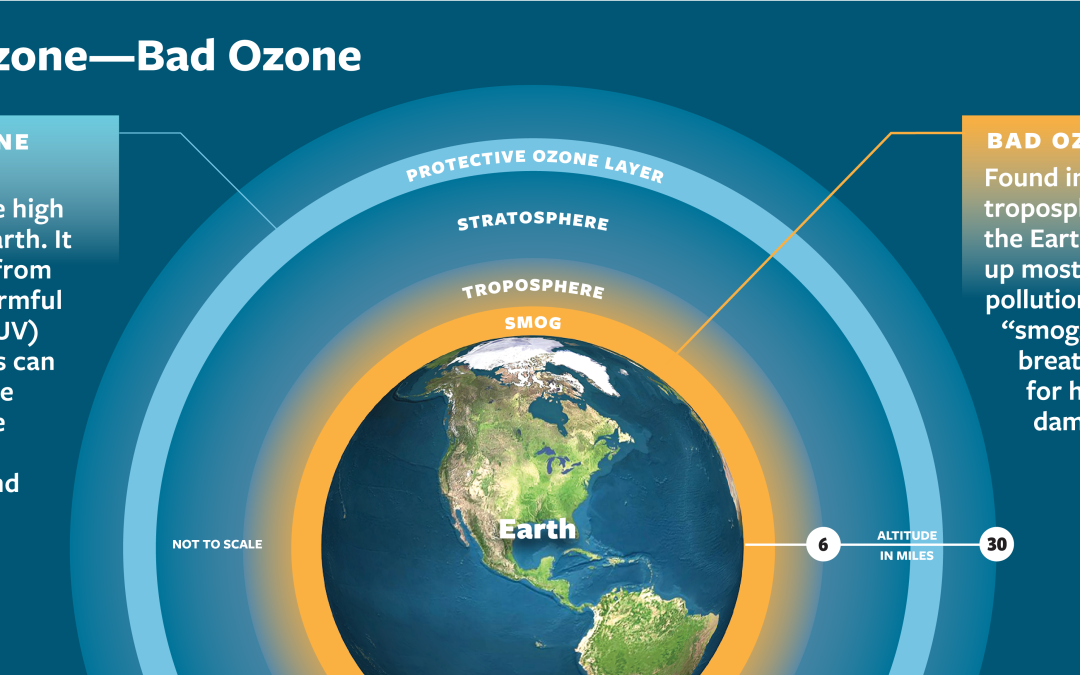

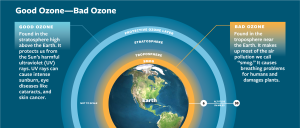

First of all, ozone (O3), also known as trioxygen, is the name we give when three oxygen molecules form a bond. It is present in low concentrations throughout the atmosphere and is important in absorbing ultraviolet (UV) radiation from the sun. This upper “ozone layer” is what we were concerned about when we noticed a hole forming in it, and regulations were put in place to minimize products that damaged this protective layer. However, ozone can also be formed lower in the atmosphere (called the troposphere) near the surface, where air pollutants, such as those related to the burning of fossil fuels and associated with smog, are produced. In this case, the ozone is considered a pollutant because it can cause health issues for animals, including humans, and can also affect plants.

Good ozone is way above our heads while the bad ozone is near the surface. Credit: National Center for Atmospheric Research.

When toxins in the environment harm plants, we call them phytotoxic. In the case of ozone, it can be phytotoxic at certain levels, and researchers are finding that certain plants seem to be more sensitive to ozone than others. The ozone damages plants by entering through the stoma, very small holes on the bottom of the leaves that the plant uses to pull in carbon dioxide and let out oxygen. Once inside the plant, ozone begins to alter normal cellular function, via oxidation, and causes visible symptoms, especially with the more sensitive plant species.

Symptoms of ozone phytotoxicity on tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera). Credit: USDA Forest Service – Region 8 – Southern , USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org

These particularly sensitive species can be used as biological indicators because they show symptoms that can be easily recognized as ozone injury. Several National Parks and other public gardens have even begun installing ozone gardens, planted with these biological indicator species, to assess the air quality of the area.

Are you interested in knowing the plants that are sensitive to ozone? Here’s a list of species, selected from a National Park Service publication (Ozone Sensitive Plant Species on National Park Service Lands), that grow in the north Florida area:

- Trumpet creeper (Campsis radicans)

- Eastern Redbud (Cercis canadensis)

- Flowering dogwood (Cornus florida)

- Tuliptree (Liriodendron tulipifera)

- American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

- Black cherry (Prunus serotina)

- Winged sumac (Rhus copallinum)

- Cutleaf coneflower (Rudbeckia laciniata)

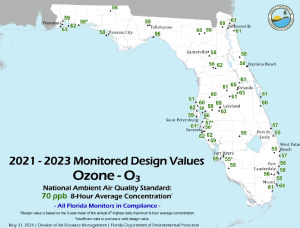

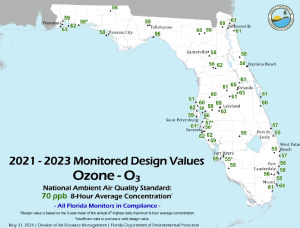

To answer the question that started this path down the ozone rabbit hole, the tree would likely be okay to plant near a road. The tree was not on the research-backed list and the ozone levels in our area generally low. Ozone levels in our part of the state average about 55-60 ppb (parts per billion), compared to the standard of 70 ppb, last set by the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 2008. Planting the tree may even be a fun, and useful, experiment to keep an eye on local air quality.

Ozone levels, as measured and reported by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. Source: FDEP.

If you’re interested in more information on the impacts of ozone on plants, the National Center for Atmospheric Research has a great website, including a map of ozone gardens across the country. For more information on ozone levels across the country or in the state of Florida, the US EPA and the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) have websites containing useful charts and maps. The good news is that surface ozone levels are generally on the decline thanks to regulations put in place to protect people and the environment. Of course, if you have any plant related questions, please contact your local extension office – we need article ideas!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 19, 2024

Problem areas in the landscape – everyone has them. Whether it’s the spot near a drain that stays wet or the back corner of a bed that sunshine never touches, these areas require specialized plants to avoid the constant frustration of installing unhealthy plants that slowly succumb and must be replaced. The problem area in my landscape was a long narrow bed, sited entirely under an eave with full sun exposure and framed by a concrete sidewalk and a south-facing wall. This bed stays hot, it stays dry, and is nigh as inhospitable to most plants as a desert. Enter a plant specialized to handle situations just like this – Yarrow ‘Moonshine’.

Yarrow (Achillea spp.) is a large genus of plants, occurring all over the globe. To illustrate, Common Yarrow (Achillea millefolium) is native to three different continents (North America, Europe, and Asia), making it one of the most widely distributed plants in the world. And though it was commonly grown and used in antiquity for medical purposes (the genus name Achillea is a reference to Achilles, who supposedly used the plant as a wound treatment for himself and his fellow Greek soldiers), I and most of you are probably more interested in how it looks and performs in the landscape.

‘Moonshine’ Yarrow foliage.

All species of Yarrow share several ornamental traits. The most obvious are their showy flowers, which occur as large, flattened “corymbs” and come in shades of white, pink, red, and yellow. I selected the cultivar ‘Moonshine’ for my landscape as it has brilliant yellow flowers that popped against the brown wall of the house. Equally as pretty and unique is the foliage of Yarrow. Yarrow leaves are finely dissected, appearing fernlike, are strongly scented, and range in color from deep green to silver. Again, I chose ‘Moonshine’ for its silvery foliage, a trait that makes it even more drought resistant than green leaved varieties.

‘Moonshine’ Yarrow inflorescence.

If sited in the right place, most Yarrow species are easy to grow; simply site them in full sun (6+ hours a day) and very well drained soil. While all plants, Yarrow included, need regular water during the establishment phase, supplemental irrigation is not necessary and often leads to the decline and rot of Yarrow clumps, particularly the silver foliaged varieties like ‘Moonrise’ (these should be treated more like succulents and watered only sparingly). Once established, Yarrow plants will eventually grow to 2-3’ in height but can spread underground via rhizomes to form clumps. This spreading trait enables Yarrow to perform admirably as a groundcover in confined spaces like my sidewalk-bound bed.

If you have a dry, sunny problem spot in your landscape and don’t know what to do, installing a cultivar of Yarrow, like ‘Moonshine’, might be just the solution to turn a problem into a garden solution. This drought tolerant, deer tolerant, pollinator friendly species couldn’t be easier to grow and will reward you with summer color for years to come. Plant one today. For more information on Yarrow or any other horticultural question, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office.

by Ray Bodrey | Sep 4, 2024

Fall is a season that is synonymous for two great joys in life…..football games and the changing leaf colors! However, in Florida we just don’t have the incredible burst of vivid fall leaf color as our northern neighbors enjoy each year, but we do have enough temperate region plants that can give us some seasonal change in foliage.

So what makes this brilliant display of autumn leaf color anyway? This seasonal change is brought on by a few variables, such as lower temperatures, shorter photo period/shorter days and chemical pigments found in leaf tissues. Some of the pigments that give autumn leaves their bright colors are actually present in the leaves as soon as they unfold as flush in early spring. But, during spring and summer, when the plants are growing vigorously, a green-colored material called chlorophyll dominates and shades out the other leaf pigments.

Chlorophyll plays on important role in a process called photosynthesis, which is the process by which plants capture energy from sunlight and manufacture food. Chlorophyll can also be found in water bodies and is an indicator of water quality. As plants get ready for cool season dormancy, the production on new chlorophyll decreases to almost being nonexistent. That’s when the before mentioned pigments, also called carotenoids, take over and make the leaves turn brilliant orange, red, purple and yellow.

There are some plants in the Florida’s landscape that do provide good fall color. Unlike most of the flowering shrubs, which hold their blossoms for only a brief period, the trees and shrubs that turn color in the fall will usually retain their varied hues for a month or more, depending on the weather.

Red Maple. Credit. UF/IFAS Extension

What are some examples of trees that will lend fall color in your Panhandle landscape?

- Shumard Oak

- Turkey Oak

- Ginkgo

- Hickory

- Golden Rain Tree

- Red Swamp Myrtle

- Dogwood

- Red Maple (see photo)

- Sweet Gum

- Black Gum

- Crape Myrtle

- Tulip Tree

- Bradford Pear

- Cypress

What about annuals that provide color in the fall? Petunias, pansies and snapdragons will be in full bloom over the next few months.

Firespike. Credit. UF/IFAS Extension

What about blooming perennials for fall? Salvia, firespike (see photo), chrysanthemum, beautyberry and holly are great for color in the fall and attract wildlife to your landscape.

A mix of these plants will ensure fall color in your landscape. For more information contact your local county extension office.

Information for this article was provided by Patrick Minogue, Forestry Specialist with UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, as well as the UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions: https://gardeningsolutions.ifas.ufl.edu/design/outdoor-living/gardening-for-fall-color/

by Daniel J. Leonard | Aug 12, 2024

Despite being a near-perfect ornamental for the Panhandle, Crape Myrtle is often misused. Though there are dozens of commercially available varieties in all shapes and sizes, many people choose the wrong one for their yard. The most commonly sold cultivars ‘Natchez’ (white flowers), ‘Muskogee’ (pink flowers), and ‘Tuscarora’ (watermelon red flowers) – all three attain mature heights more than 20’ – are almost always too large for siting near a house or other structure and are often out of scale with landscapes. The simple solution to making the best use of Crape Myrtle in smaller yards (certainly not dramatic pruning – Crape Murder is among the worst landscape sins), is to select a smaller growing variety and ‘Tonto’ is a personal favorite in this category.

‘Tonto’ Crape Myrtle, one of the selections that emerged from Dr. Don Egolf’s Crape Myrtle breeding program at the U.S. National Arboretum over 50 years ago, is among my favorite Crape Myrtle varieties for several reasons. First, Tonto’s fuchsia hued flowers are as vibrant as flowers come; they practically glow in the landscape. The flower show lasts for several months and are a valuable food source for pollinators, bees in particular, in the late summer when few things are blooming. Tonto also is a relatively slow grower that only reaches about 10’ tall and wide at maturity. This allows the variety to be exceedingly versatile in landscapes as it can be used in the background of planting beds, as a specimen plant, limbed up as a small tree in open areas, or even placed in very large containers. Finally, beyond just the flower show and ideal size, ‘Tonto’ has uniquely attractive, cream colored, exfoliating bark and reliably attractive fall foliage. Both these features add interest to landscapes, even when ‘Tonto’ isn’t flowering.

Though ‘Tonto’ sports many unique qualities, it shares many other excellent traits and growing preferences with its Crape Myrtle kin. For best results growing any Crape Myrtle, trees should always be sited in full sun, at least 6-8 hours a day. Shading will result in greatly reduced flowering and lanky plants. Regular watering during the first year after planning while trees are becoming established is helpful, as is periodic fertilizer application. Once established, ‘Tonto’ and all other Crape Myrtles are exceedingly drought tolerant and can get by on their own with minimal inputs from gardeners.

If you’ve been struggling with a Crape Myrtle that has outgrown its site or thinking about planting a new Crape, I’d encourage you to give ‘Tonto’ a look. It’s an outstanding shrub/small tree, will reward you with flaming fuchsia flowers and smooth cream-colored bark each summer, and will never outgrow its space. Plant one today! For more information on growing Crape Myrtles or any other horticultural topic, contact us at the UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension Office. Happy gardening.

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.