by Carrie Stevenson | May 1, 2017

The Southeastern blueberry bee uses buzz pollination on a blueberry plant. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS.

This time of year, blueberry bushes are flowering and small fruit are coming onto the wild and cultivated bushes in north Florida. Many of us, myself included, look forward to the late-spring harvest of blueberries, taking our children out to u-pick operations and digging out family recipes for blueberry-filled desserts.

What many do not know, however, is that there’s a specialized bee that literally lives for this season. During the last few weeks, this little insect has been furiously pollinating blueberry bushes during its short, single-purpose lifetime.

The Southeastern blueberry bee, Habropoda labriosa is active only in mid-March to April when blueberry plants are in flower. They are smaller than bumblebees, and the yellow patches on their heads can differentiate males. Blueberry pollen is heavy and sticky, so it is not blown by the wind, and the flower anatomy is such that pollen from the male anther will not just fall onto the female stigma. Blueberry bees must instead attach themselves to the flower and rapidly vibrate their flight muscles, shaking the pollen out. Moving to the next flower, the bee’s vibrations will drop pollen from the first flower onto the next one. This phenomenon is called “sonicating” or ‘buzz pollination” and is the most effective method of creating a prolific blueberry crop.

Blueberry bees do not form hives, but create solitary nests in open, sunny, high ground. Females will dig a tunnel with a brood chamber large enough for one larva, filling it with nectar and pollen. After laying an egg, the female seals the chamber and the next generation is ready. The species produces only one generation of adults per year.

By the time we are picking fresh blueberries next month, you probably won’t see any blueberry bees around. However, we should all consider these insects’ short-lived but vitally important role in Florida’s $82 million/year blueberry industry!

For more information, check out the beautifully illustrated USDA Forest Service publication, “Bee Basics—An Introduction to our Native Bees,” or North Carolina State University’s entomology website.

by Gary Knox | Oct 7, 2016

A “Gardening for Pollinator Conservation” Workshop will take place Thursday, October 13, at the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy. Pollinators are important in conserving native plants, ensuring a plentiful food supply, encouraging biodiversity and helping maintain a healthier ecological environment – – – the so-called “balance of nature.” Come learn how you can conserve and promote pollinators in your own garden, all while beautifying your own little piece of Nature.

A “Gardening for Pollinator Conservation” Workshop will take place Thursday, October 13, at the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy. Pollinators are important in conserving native plants, ensuring a plentiful food supply, encouraging biodiversity and helping maintain a healthier ecological environment – – – the so-called “balance of nature.” Come learn how you can conserve and promote pollinators in your own garden, all while beautifying your own little piece of Nature.

As in previous years, nursery vendors will be selling pollinator plants at the Oct. 13 workshop, making it convenient for you to put into practice what you learn at the workshop! Registration is just $15 per person and includes lunch, refreshments, and handouts.

Check out the workshop details and register at: https://gardeningforpollinatorconservation.eventbrite.com/

What: Gardening for Pollinator Conservation

When: Thursday, October 13, 8:30 am to 5:00 pm EDT

Where: University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, 155 Research Road, Quincy, FL. Located just north of I-10 Exit 181, 3 miles south of Quincy, off Pat Thomas Highway, SR 267.

Cost: $15 per person (includes lunch, refreshments and handouts)

Registration: https://gardeningforpollinatorconservation.eventbrite.com

For more information, contact: Gary Knox, gwknox@ufl.edu; 850.875.7105

For a printable Flyer click here: Gardening for Pollinators Workshop

Our workshop builds on previous successful pollinator workshops held at Leon Co. Extension last year and in Marianna in 2012. This workshop was developed as a collaboration of county faculty from several extension offices with folks from the Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission as well as UF/IFAS NFREC. Sponsors helping defray costs include Florida Native Plant Society – Magnolia Chapter, Gardening Friends of the Big Bend, Inc., Mail-Order Natives, and University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center.

We look forward to seeing you at the workshop!

by Mary Salinas | Sep 22, 2016

Monarch butterfly on dense blazing star (Liatris spicata).

Beverly Turner, Jackson Minnesota, Bugwood.org

The Florida panhandle has a treasure of native wildflowers to enjoy in every season of the year. In the late summer and fall, blazing star, also commonly known as gayfeather, can be found blooming in natural areas and along roadsides. You can also add it to your landscape to provide beautiful fall color and interest year after year.

Blazing star is a perennial that is native to scrubs, sandhills, flatwoods and upland pines; this makes it a tough plant that can endure drought conditions once it is established. It is ideal for a low-maintenance landscape and is a perfect addition to a butterfly or pollinator garden. The butterflies and bees love it!

Scaly blazing star (Liatris squarrosa). Photo credit: Vern Wilkins, Indiana University, Bugwood.com.

This beauty grows tall and slender so it is best when planted in masses for an impressive display. This lankiness can result in lodging, or falling over, when the blooms get too heavy but this can be alleviated when grown in masses or with other wildflowers that can support them. The spent flowers will provide your garden with more seed for future years and form a larger colony.

Chapman’s Blazing Star (Liatris chapmanii). Photo credit: Mary Derrick, UF/IFAS.

The home gardener can add blazing star as potted plants or by seeding directly into the soil in October in north Florida. Seeds are available from numerous online sources. Before you purchase, however, make sure that the species you select is a Florida native!

For more information and seed sources:

Florida Wildflower Foundation

Common Native Wildflowers of North Florida

by Julie McConnell | Sep 16, 2016

Bee visiting Monarda punctata. Photo: J. McConnell, UF/IFAS

If you are looking for a late summer blooming plant that attracts pollinators and survives in a tough spot, dotted horsemint (Monarda punctata) is for you! This native plant thrives in sunny, well-drained sites but will also tolerate moist garden spots. It grows quickly and blooms prolifically – attracting pollinators by the dozens. A plant covered in blooms is very showy and when you go in for a closer look, you’ll see unique flowers.

Dotted horsemint brings color to the summer garden. Photo: J. McConnell, UF/IFAS

This plant can get 3 feet tall by 4 feet wide but it is tolerant of pruning in the growing season to keep it tidy and encourage bushiness. Just be sure to prune it before it sets flowers, a good rule of thumb is to prune before the end of June.

Propagation is by division or seed. Few pests affect dotted horsemint.

To read more about this flowering perennial:

Monarda punctata Bee Balm, Horsemint

by Sheila Dunning | Jun 22, 2016

The showy chaste tree makes an attractive specimen as the centerpiece of your landscape bed or in a large container on the deck. Easy-to-grow, drought resistant, and attractive to butterflies and bees, Vitex agnus-castus is a multi-stemmed small tree with fragrant, upwardly-pointing lavender blooms and gray-green foliage. The chaste tree’s palmately divided leaves resemble those of the marijuana (Cannabis sativa) plant; its flowers can be mistaken for butterfly bush (Buddleia sp.); and the dry, darkened drupes can be used for seasoning, similar to black pepper, making it a conversation piece for those unfamiliar with the tree.

The showy chaste tree makes an attractive specimen as the centerpiece of your landscape bed or in a large container on the deck. Easy-to-grow, drought resistant, and attractive to butterflies and bees, Vitex agnus-castus is a multi-stemmed small tree with fragrant, upwardly-pointing lavender blooms and gray-green foliage. The chaste tree’s palmately divided leaves resemble those of the marijuana (Cannabis sativa) plant; its flowers can be mistaken for butterfly bush (Buddleia sp.); and the dry, darkened drupes can be used for seasoning, similar to black pepper, making it a conversation piece for those unfamiliar with the tree.

Vitex, with its sage-scented leaves that were once believed to have a sedative effect, has the common name “Chastetree” since Athenian women used the leaves in their beds to keep themselves chaste during the feasts of Ceres, a Roman festival held on April 12. In modern times, the tree is more often planted where beekeepers visit in order to promote excellent honey production or simply included in the landscape for the enjoyment of its showy, summer display of violet panicles.

Chaste tree is native to woodlands and dry areas of southern Europe and western Asia. It will thrive in almost any soil that has good drainage, prefers full sun or light shade, and can even tolerate moderate salt air. Vitex is a sprawling plant that grows 10-20 feet high and wide, that looks best unpruned. If pruning is desired to control the size, it should be done in the winter, since it is a deciduous tree and the blooms form on new wood. The chaste tree can take care of itself, but can be pushed to faster growth with light applications of fertilizer in spring and early summer and by mulching around the plant. There are no pests of major concern associated with this species, but, root rot can cause decline in soils that are kept too moist.

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 21, 2016

Mountain laurel. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning, UF/IFAS Extension.

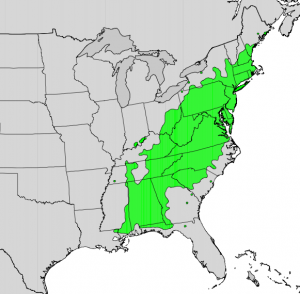

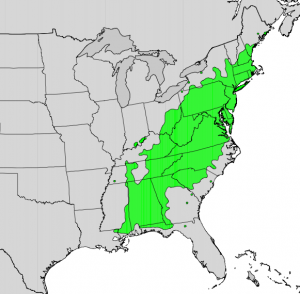

If you are lucky enough to live on the southern Alabama edge of northwest Florida, you may want to see if you can find mountain laurel blooming now near the wooded creeks. Its native range stretches from southern Maine south to northern Florida, just dipping into our area. The plant is naturally found on rocky slopes and mountainous forest areas. Both are nearly impossible to find in Florida. However, it thrives in acidic soil, preferring a soil pH of 4.5 to 5.5 and oak-healthy forests. That is something we do have. The challenge is to find a cool slope near spring-fed water.

Mountain laurel blooms. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning, UF/IFAS Extension.

Mountain laurel (Kalmia latifolia) was first recorded in America in 1624, but it was named after Pehr Kalm, who had collected and submitted samples to Linnaeus in the 18th century. The wood of mountain laurel was popular for small household items. It is heavy and strong with a close, straight grain. However, as it grow larger it becomes brittle. Native Americans used the leaves as an analgesic. But, all parts of the plant are toxic to horses, goats, cattle, deer, monkeys and humans. In fact, food products made from it, including honey, can produce neurotoxic and gastrointestinal symptoms in people consuming more than a modest amount. Luckily, the honey is usually so bitter that most will avoid eating it.

Mountain laurel in its native habitat. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning, UF/IFAS Extension.

One of the most unusual characteristics of mountain laurel is its unique method of dispersing pollen. As the flower grows, the filaments of its stamens are bent, creating tension. When an insect lands on the flower, the tension is released, catapulting the pollen forcefully onto the insect. Scientific experiments on the flower have demonstrated it ability to fling the pollen over 1/2 inch. I guess if you don’t taste that good, you have to find a way to force the bees to take pollen with them.

The mountain laurel in these pictures is from Poverty Creek, a small creek near our office in Crestview. This is their best bloom in 10 years. Maybe you can find some too.

Native range of mountain laurel.