by Larry Williams | Feb 11, 2021

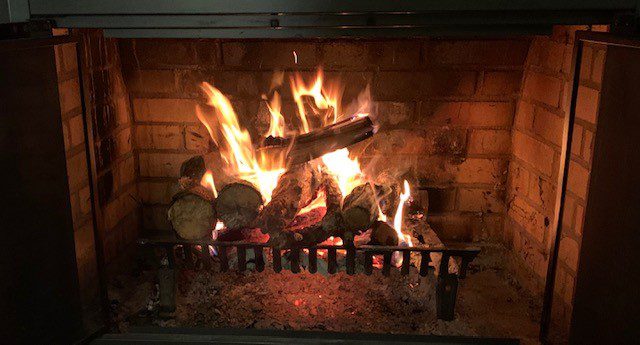

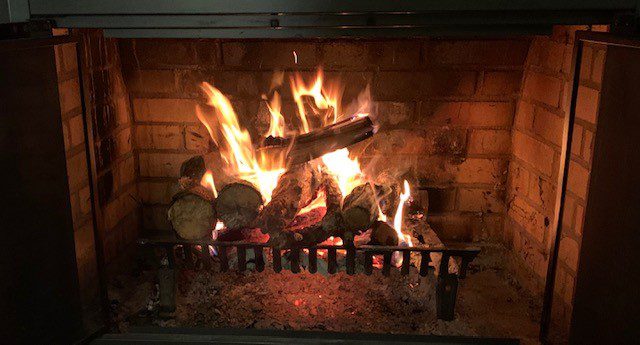

Be careful when bringing firewood indoors. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Your firewood pile could be “bugged.” Many insects like to overwinter in wood. A wood pile is an ideal place for some insects to survive the winter. They don’t know that you intend to bring their winter home indoors during cold weather.

During colder weather, you can unknowingly bring in pests such as spiders, beetles and roaches when you bring in firewood. It’s best to bring in firewood only when you are ready to use it. Otherwise, those pests could become active and start crawling around inside your house. Many insects are potential problems indoors and there are usually control options once insects move into your home. However, preventing the insects from getting inside is the best approach.

If you store wood indoors for short periods of time, it is a good idea to clean the storage area after you have used the wood. Using a first-in, first-out guideline as much as possible will reduce chances of insect problems.

It’s best to keep your wood pile off the ground and away from the house. This will make it less inviting to insects and help the wood dry. It’s not difficult to keep the wood off the ground. The wood can be stacked on a base of wooden pallets, bricks or blocks, which will allow air movement under the wood. The wood can also be covered with a waterproof tarp or stored in a shed. Regardless of how it is stored, avoid spraying firewood with insecticides. When burned, insecticide treated wood may give off harmful fumes.

Some critters that live in firewood can be harmful to humans. To avoid a painful sting or bite from insects, spiders or scorpions (no Florida scorpion is considered poisonous, but they can inflict a painful sting), it is a good practice to wear gloves when picking up logs from a wood pile.

Firewood can be a good source of heat during our cold weather. If you’re careful with how you handle your firewood, hopefully it will warm you, not “bug” you.

by Matthew Orwat | Aug 31, 2020

Citrus Rust Mite “sharkskin” closeup – Image Credit Matthew Orwat, UF / IFAS Extension

In recent years, not a summer has gone by in which I did not see citrus rust mite (CRM) damage in a garden. I thought this year would be the first. Unfortunately, recently I saw my first rust mite damage of the year.

Unlike the myriad of pests that have been recently introduced into Florida from abroad, the citrus rust mite (Phyllocoptruta oleivora) has been documented as present in Florida since the late 1800s. Along with its companion, pink citrus rust mite (Aculops pelekassi) It can be a major summer pest for satsuma mandarins grown in the Florida Panhandle gardens.

Citrus Rust Mite (CRM) damage manifests itself on fruit in two ways, “sharkskin” and “bronzing“. Sharkskin is caused when mites have fed on developing fruit, and destroyed the top epidermal layer. As the fruit grows, the epidermal layer breaks and as the fruit heals, the brown “sharkskin” look develops. Bronzing occurs when rust mites feed on fruit that’s nearer to mature size. Since the skin is not fractured by growth, the fruits develop a polished bronze look. In both cases, the interior of the fruit may remain undamaged. However, extreme damage can cases cause fruit drop and reduced fruit size. Regardless of the condition of the interior, damaged fruit is not aesthetically pleasing, but fine for slicing or juicing.

“Sharkskin Damage” to fruit caused by past feeding by the Citrus Rust Mite. Image Credit, Matthew Orwat

If a CRM population is present, they will begin increasing on fresh spring new growth in late April, and usually reach peak levels in June and July. By August the damage has often already been done, but is first noticed due to the increased growth of the fruit. Depending upon weather conditions, CRM can have a resurgence in October and November, just as Satsuma and other citrus is getting ready to be harvested, so careful monitoring is necessary. For more information, check out this publication: Guide to Citrus Rust Mite Identification.

Sun spot resulting from where citrus rust mite avoids feeding on most sun exposed portion of the fruit. Image and Caption courtesy of EDIs publication HS-806

If control of CRM is warranted, there are several miticides available for use, but it is not advisable for home gardeners to use these on their citrus plants since they will also kill beneficial insects. Horticultural oil is an alternative to miticide, which is less damaging to beneficial insects. Several brands of horticultural oil are formulated to smother CRM, but care must be taken to not apply horticultural oil when daytime temperatures will reach 94 degrees Fahrenheit. Application of oils at times when temperatures are at this level or higher will result in leaf and fruit damage.

Although Citrus Rust Mite (CRM) has the potential to be aesthetically unsightly on citrus fruit in the Florida Panhandle, strategies of monitoring and treatment in homeowner citrus production have been successful in mitigating their damage.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jul 29, 2020

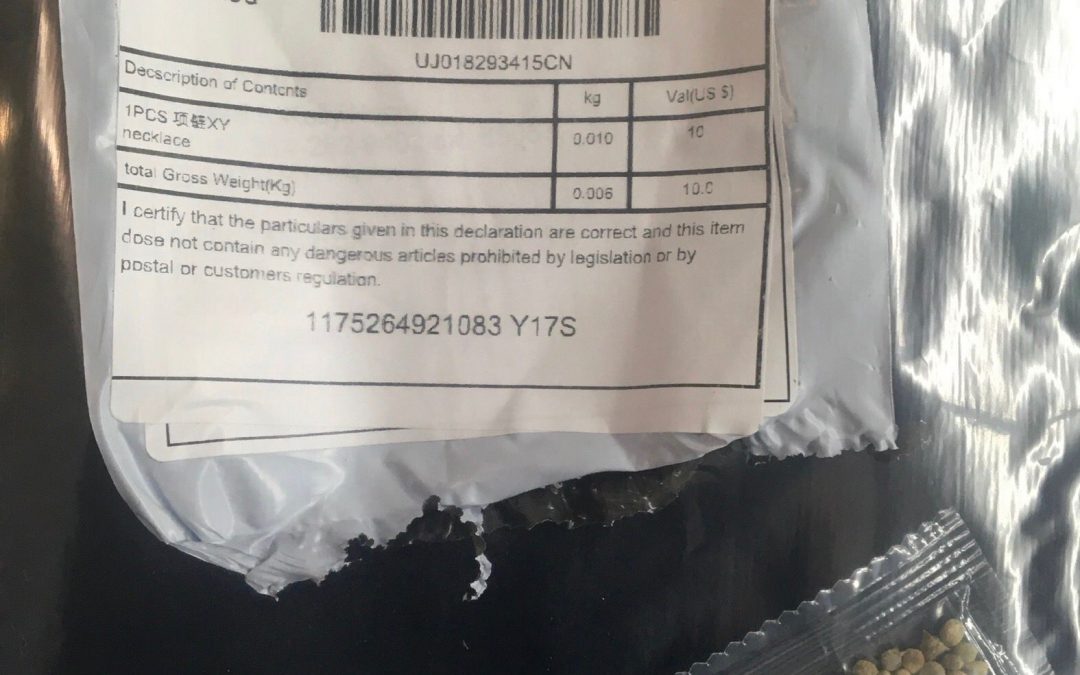

If you’ve paid attention at all to the news recently or been on social media, you’ve no doubt seen the flood of stories about mysterious seeds arriving in thousands of Americans’ mailboxes from various addresses in China. The packages may be labelled as jewelry or other common items, may have postage written in Chinese characters and have been documented in multiple states, including Florida. Little else is currently known about the seed packages and it has not yet been documented if the seeds are harmful invasive species or carry other pathogenic organisms that could wreak havoc on local ecosystems. The illicit introduction of seeds from abroad is a serious concern and is being closely monitored and investigated nationally by the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) and locally by the Florida Department of Agriculture (FDACS) Division of Plant Industry.

Photo courtesy of the Kentucky Department of Agriculture.

How or why these seeds have made it to Floridian’s doorsteps and P.O. boxes is still anyone’s guess, but the bottom line is that the shipping of undocumented plant material into and out of the U.S. is illegal and potentially hazardous to people, the economy, and the environment. Here’s what to do if one of these packages of seeds shows up in your mailbox:

- Do not open the seed packets and avoid opening outer packaging or mailing materials.

- Do not plant any of the seeds.

- Do not dispose of the seeds; releasing them into our local ecosystems could prove harmful.

- Limit contact with the seed package until further guidance on handling, disposal, or collection is available from USDA.

- Report the seeds to your local UF/IFAS Extension office. Your local Extension Agent will be able to help you document and ensure that the seeds are reported to the correct authorities.

- Make sure the seeds get also get reported to the FDACS Division of Plant Industry at 1-888-397-1517 or online at DPIhelpline@FDACS.gov

by Larry Williams | Jul 9, 2020

If you’ve been outside this spring, you’ve probably been bothered by gnats. These tiny flies relentlessly congregate near the face getting into the eyes, nose, mouth and ears.

Eye gnats come right up to the faces of people and animals because they feed on fluids secreted by the eyes, nose and ears. Even though eye gnats are considered mostly a nuisance, they have been connected to transmission of several diseases, including pink eye.

Close up of eye gnat. Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF Entomologist

Eye gnats are true flies. At about one-sixteenth of an inch in length, they are among the smallest fly species in Florida. They are known as eye gnats, eye flies, frit flies and grass flies. The name grass flies is somewhat descriptive as open grass areas such as pastures, hay fields, roadsides and lawns provide breeding sites for these gnats. They also breed in areas of freshly disturbed soil with adequate organic matter such as livestock farms.

Even though these gnats can be found in much of North and South America, they prefer areas with warm, wet weather and sandy soils. Sounds like Florida.

The lack of cold weather in late winter and early spring is the more likely reason for why these gnats are such a problem in our area this year. Without having the typical last killing frost around mid-March and with early warm weather and rains, the gnats got off to an early start.

Short of constantly swatting them away from your face or just not going outdoors, what can be done about these irritating little flies?

By the way, I grew up in an area of Georgia where gnats are common. I’ll let you in on a secret… Folks who live in Georgia are known to be overly friendly because they are always waving at people who are just passing through. More than likely, these “friendly” folks are busy swatting at gnats, not waving at others who happen to be driving by. Swatting is a quick swinging action with hand as if waving.

Because of their life cycle, extremely high reproductive numbers in the soil and because insecticides breakdown quickly, area-wide chemical control efforts don’t work well in combating this insect.

The use of the following where gnats are common can be helpful.

- Correct use of insect repellents, particularly those containing DEET

- Screens on windows to prevent entry of gnats into homes

- Face-hugging sunglasses or other protective eyewear

- Face masks – another use for your COVID-19 face mask

We may have to put up with these annoying gnats until cold weather arrives and be thankful that they don’t bite.

Additional info on eye gnats is available online at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in884 or from the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your County.

by Larry Williams | Jun 23, 2020

The 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season got off to an early start with some tropical storm activity before the season’s official June 1 start date. We live in a high wind climate. Even our thunderstorms can produce fifty-plus mile per hour winds.

Storm damaged sweetgum tree. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Preventive tree maintenance is key to preparing for storms and high winds.

Falling trees and flying landscape debris during a storm can cause damage. Evaluate your landscape for potential tree hazards. Pruning or removing trees once a hurricane watch has been announced is risky and tree trimming debris left along the street is hazardous.

Now is a good time to remove dead or dying trees, prune decayed or dead branches and stake newly planted trees. Also inspect your trees for signs of disease or insect infestation that may further weaken them.

Professional help sometimes is your best option when dealing with larger jobs. Property damage could be reduced by having a professional arborist evaluate unhealthy, injured or questionable trees to assess risk and treat problems.

Hiring a certified arborist can be a worthwhile investment. To find a certified arborist in your area, contact the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA) at 888-472-8733 or at www.isa-arbor.com. You also may contact the Florida ISA Chapter at 941-342-0153 or at www.floridaisa.org.

Consider removing trees that have low wind resistance, are at the end of their life span or that have the potential to endanger lives or property.

Some tree species with the lowest wind resistance include pecan, tulip poplar, cherry laurel, Bradford pear, southern red oak, laurel oak, water oak, Chinese tallow, Chinese elm, southern red cedar, Leyland cypress, sand pine and spruce pine.

Broken pine from hurricane. Photo credit: Larry Williams

Pine species vary in their wind resistance, usually with longleaf and slash pines showing better survival rates than loblolly and sand pine. However, when pines become large, they may cause a lot of damage if located close to homes or other valuable structures. As a result, large pines are classified as having medium to poor wind-resistance. For this reason, it’s best to plant pines away from structures in more open areas.

Before and after a storm, tree removal requires considerable skill. A felled tree can cause damage to the home and/or property. Before having any tree work done, always make sure you are dealing with a tree service that is licensed, insured and experienced.

More information on tree storm damage prevention and treatment is available online at http://hort.ifas.ufl.edu/woody/stormy.shtml or from the UF/IFAS Extension Office in your County.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2020

Fig. 1 An adult redbay ambrosia beetle compared to the size of a single penny. Credit: UF/IFAS File Photo.

While most bark beetles are important in forest ecology by recycling fallen dead trees and eliminating sick and damaged trees, some of them may impact healthy trees. A group of bark beetles that has become a major concern to forest managers, nurseries, and homeowners is the ambrosia beetle. Ambrosia beetles are extremely small, 1-2 mm in length, and live and reproduce inside the wood of various species of trees (Fig. 1). Ambrosia beetles differ from other bark beetles in that they do not feed directly on wood, but on a symbiotic fungus that digests wood tissue for them. Every year, non-native species of ambrosia beetles enter the United States through international cargo and we have now nearly forty non-native species of ambrosia beetles confirmed in the United States. Among them, the redbay ambrosia beetle (Xyleborus glabratus), originally from Southeast Asia, is the vector of the fungal pathogen causing laurel wilt, a disease that devastated the Lauracaea population in the southeastern USA, killing millions of redbay, swamp bay, sassafaras and silk bay.

Fig. 2: A mature dooryard avocado tree with large sections of dead and missing leaves, caused by laurel wilt disease. Summer 2009 Impact Magazine image. Credit: UF/IFAS File Photo.

When these beetles attack a laurel tree, the symbiotic fungus is vectored to the tree’s sapwood after the beetle has tunneled deep into the tree’s xylem, actively colonizing the tree’s vascular system. This colonization leads to an occlusion of the xylem, causing wilting of individual branches and in a matter of weeks progresses throughout the entire canopy, eventually leading to tree death (Fig. 2). The laurel wilt disease has spread rapidly after the vector was first detected in Georgia in 2002. The redbay ambrosia beetle was first detected in Florida in 2004, in Duval County, attacking redbay and swamp bay trees. At this point, it is estimated that more than one-third of redbay in the U.S.A., 300 million trees, have succumbed to the disease.

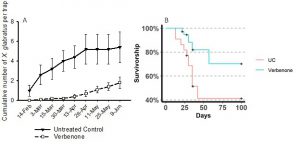

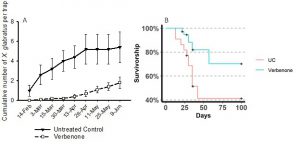

Starting in 2017, we examined the efficacy of verbenone against redbay ambrosia beetle in live laurel trees in a natural forest setting. Verbenone is an anti-aggregation pheromone that has been used since the 1980’s to protect lodgepole pine. Verbenone also has the potential to be used over large areas and is currently being used to protect ponderosa pine plantations from the Mountain Pine Beetle in the western US.

We have found verbenone to be an environmentally friendly and safe tool to prophylactically protect laurel trees against redbay ambrosia beetle. Our protocol consists of the application of four 17 g dollops of a slow-release wax based repellent (SPLAT Verb®, ISCA technology of Riverside, CA) to the trunk of redbay trees at 1 – 1.5 m above ground level (Fig. 3). The wax needs to be reapplied every 4 months during fall and winter and every 3 months during spring and fall when temperature is higher. When compared to the control trees without repellents, we found that trunk applications of verbenone reduced landing of the redbay ambrosia beetle on live redbay trees and increased survivorship of laurel trees compared to untreated trees (Fig. 4). Verbenone should be considered as part of a holistic management system against redbay ambrosia beetle that also includes removal and chipping of contaminated trees.

If you have Redbay or other bay species on your property and are concerned about Laurel Wilt Disease or Redbay Ambrosia Beetle damage, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!

This article is courtesy of Dr. Xavier Martini and Mr. Derek Conover of the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy.

Fig. 3: Application of SPLAT Verb on a redbay tree during a field trial

Figure 4: (A): Cumulative capture of redbay ambrosia beetles Xyleborus glabratus following a single application of verbenone vs untreated control (UC). (B) Survivorship of redbay and swamp bay trees treated with verbenone on four different studies conducted in 2017 and 2018.