by Larry Williams | Apr 23, 2020

One of the things to do while stuck at home due to COVID-19 restrictions, is to look for caterpillars and butterflies in your landscape. I’ve noticed giant swallowtail butterflies (Papilio cresphontes) a little early this year. The giant swallowtail is one of the largest and most beautiful butterflies in our area. Its larval stage is known as the orangedog caterpillar. This unusual name comes from the fact that it feeds on young foliage of citrus trees.

Orangedog caterpillar. Photo credit: Donald Hall, University of Florida

The orangedog caterpillar is mostly brown with some white blotches, resembling bird droppings more than a caterpillar. When disturbed, it may try to scare you off by extruding two orange horns that produce a pungent odor hard to wash off.

I’ve had some minor feeding on citrus trees in my landscape from orangedog caterpillars. But I tolerate them. I’m not growing the citrus to sell. Sure the caterpillars eat a few leaves but my citrus trees have thousands of leaves. New leaves eventually replace the eaten ones. I leave the caterpillars alone. They eat a few leaves, develop into chrysalises and then emerge as beautiful giant swallowtail butterflies. The whole experience is a great life lesson for my two teenagers. And, we get to enjoy beautiful giant swallowtail butterflies flying around in our landscape and still get plenty of fruit from the citrus trees. It is a win, win, win.

In some cases, the caterpillars can cause widespread defoliation of citrus. A few orangedog caterpillars can defoliate small, potted citrus trees. Where you cannot tolerate their feeding habits, remove them from the plant. But consider relocating the caterpillars to another area. In addition to citrus, the orangedog caterpillars will use the herb fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) and rue (Ruta graveolens) as a food source. Some butterfly gardens plant citrus trees to provide food for orangedog caterpillars so that they will have giant swallowtail butterflies. So you could plan ahead and grow some fennel, rue or find a butterfly garden in your area for the purpose of relocating the larvae.

Yellow giant swallowtail butterfly on pink garden phlox flowers. Photo credit: Larry Williams

The adult butterflies feed on nectar from many flowers, including azalea, bougainvillea, Japanese honeysuckle, goldenrod, dame’s rocket, bouncing Bet and swamp milkweed. Some plants in this list might be invasive.

Keep in mind that mature citrus trees can easily withstand the loss of a few leaves. If you find and allow a few orangedog caterpillars to feed on a few leaves of a mature citrus tree in your landscape, you and your neighbors might get to enjoy the spectacular giant swallowtail butterfly.

More information on the giant swallowtail butterfly is available online at http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in134.

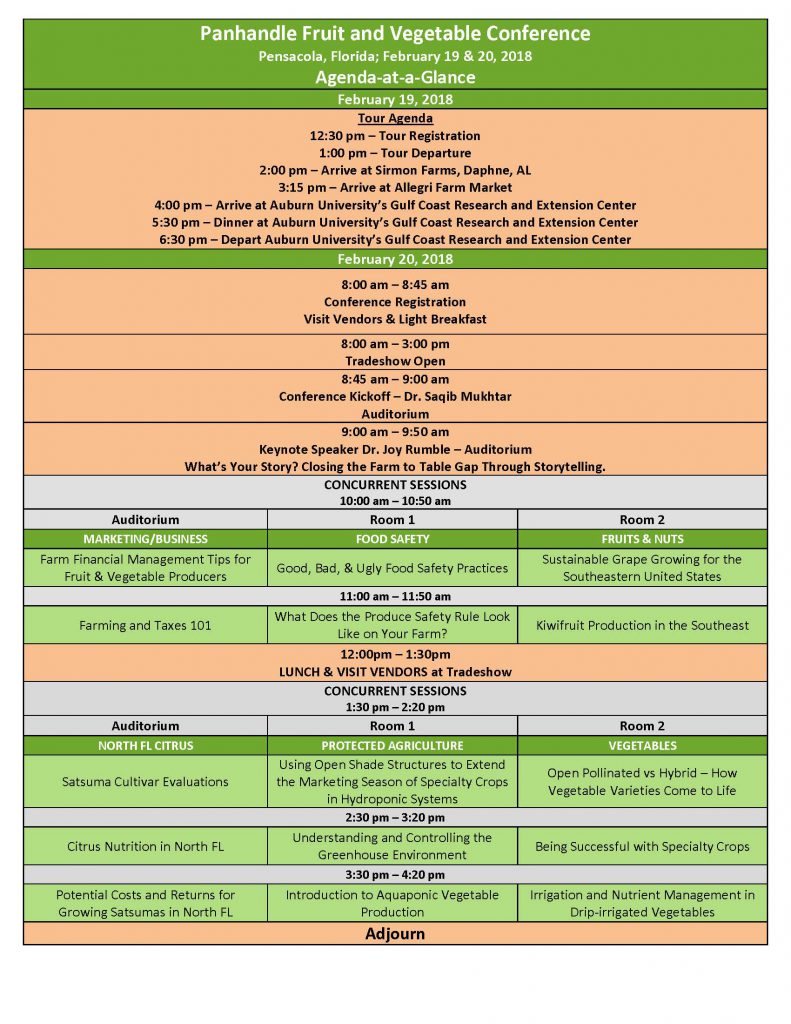

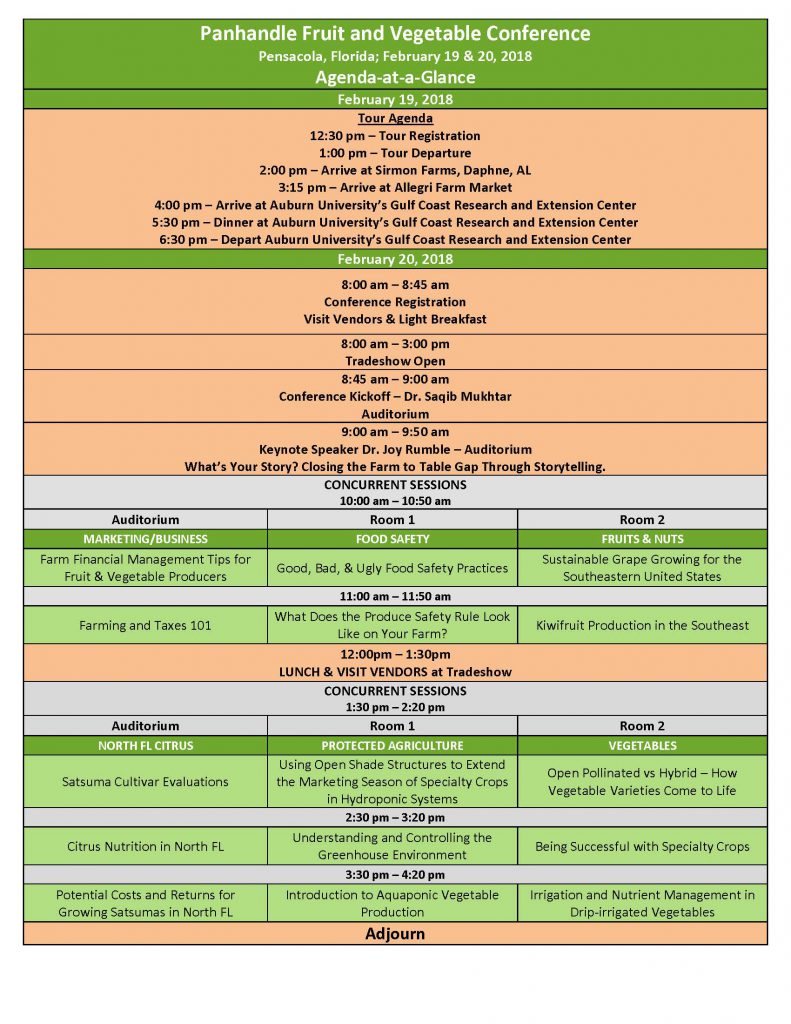

by Matt Lollar | Feb 14, 2018

Register today for the 2018 Panhandle Fruit & Vegetable Conference! The Panhandle Fruit & Vegetable Conference is scheduled for February 19th & 20th. On the 19th we will go on an afternoon farm tour in Baldwin County, AL that will end with dinner (included) at Auburn University’s Gulf Coast Research and Extension Center in Fairhope. Educational sessions with guest speakers from University of Florida, Auburn University, and Texas A&M University will be held on February 20th where topics will include Citrus Production, Vegetable Production, Protected Ag Production, Marketing/Business, Food Safety, and Fruit & Nut Production. A full list of topics can be found here. Fifty dollars (plus $4.84 processing fee) covers the tour and dinner on the 19th and educational sessions, breakfast, and lunch on the 20th! The complete agenda is now available. Use your mouse or finger to “click” on the image below for full screen viewing.

Make sure to register by Wednesday, February 14th! – Registration Link

by Mary Salinas | Feb 16, 2016

As you have read in other articles in this blog, it is too early to fertilize your lawn; however, this is a good time to start fertilizing your citrus to ensure a healthy fruit crop later in the year.

Orange grove at the University of Florida. UF/IFAS photo by Tara Piasio.

Citrus benefits from regular fertilization with a good quality balanced citrus fertilizer that also contains micronutrients. A balanced fertilizer has equal amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium such as a 6-6-6, 8-8-8 or a 10-10-10. The amount of fertilizer to be applied will vary on the formulation; for example you will need less of a 10-10-10 than a 6-6-6 as the product is more concentrated. Always consult the product label for the correct amount to use for your particular trees. Fertilizer spikes are not recommended as the nutrients are concentrated in small areas and not able to be widely available to all plant roots.

The number of fertilizations per year will vary depending on the age of the tree. Trees planted the first year need 6 light fertilizations that year starting in February with the last application in October. In following years, decrease the number of fertilizations by one per year until the fifth year when it is down to 3 fertilizations per year. From then on, keep fertilizing 3 times per year for the life of the tree. Good quality citrus fertilizer will have accurate and specific instructions on the label for the amount and timing of fertilizer application.

Fertilizer should be spread evenly under the tree but not in contact with the trunk of the tree. Ideally, the area under the drip line of the tree should be free of grass, weeds and mulch in order for rain, irrigation and fertilizer to reach the roots of the tree and provide air movement around the base of the trunk.

If you have not in recent years, obtain a soil test from your local extension office. This can detect nutrient deficiencies, which may be corrected with additional targeted nutrient applications.

For more information:

Citrus Culture in the Landscape

by Alex Bolques | Sep 2, 2013

Gardeners that have Satsumas, commonly known as orange mandarin (Citrus reticulate), probably have experienced a caterpillar called Orangedog. It is a chewing insect that feeds on citrus foliage including Satsuma and a few other plant species. The caterpillar is dark brown with creamy-white, mottled markings and is the larval stage of the giant swallowtail (Papilio cresphontes). It is a striking, wonderfully “exotic”-looking butterfly that is very abundant in Florida.

Young larva of the giant swallowtail, Illustrating bird dropping mimicry.

Credit:

Donald Hall, University of Florida

Many who have encountered the caterpillar for the first time describe them as looking similar to bird droppings. They can grow up to 1.5 to 2 inches in length and are the larval stage of the adult giant swallowtail butterfly. Established Satsuma trees can easily withstand the loss of a few leaves by Orangedog feeding. Small or newly planted Satsumas can be infested with numerous Orangedog Caterpillars on occasion, especially a single tree growing in a landscape.

A simple control measure consists of finding and crushing eggs and larva (GH-026). Bt, a biological control for most caterpillar species, is effective but should rarely be used since the beauty of this butterfly far outweighs the damage caused by them.

Adult giant swallowtail, with wings closed.

Credit:

Donald Hall, University of Florida

.

by Matthew Orwat | Feb 15, 2013

According to the National Weather Service a mild freeze is predicted for Northwest Florida this weekend, specifically Saturday night to Sunday morning. Washington County Horticulture extension agent Matthew Orwat says,” While mature, dormant Satsuma trees are cold hardy down to 14° – 18 °F, young trees need protection if temperatures dip into the upper 20s.”

Photo Credits David Marshall

Here are a few techniques to protect young citrus trees from late-season freezes:

- Wrap the trunk with commercial tree wrap or mound soil around the base of the tree up to 2 feet. This will protect the graft of the young tree. Thus, if the branches freeze the graft union will be protected.

- Cover the tree with a cloth sheet or blanket. For additional protection, large bulb Christmas lights may be placed around the branches of the tree. This will increase the temperature under the cover by several degrees. Be sure to use outdoor lights and outdoor extension cords to avoid the potential of fire.

- Water your Satsuma trees. Well watered trees have increased cold hardiness.

- Frames may be installed around young trees to hold the cover. This option keeps the blanket or sheet from weighing down the branches.

- For homeowners with lemon, lime or other less cold hardy citrus, micro-irrigation is an option. This practice will protect citrus trees up to 5 feet, but must be running throughout the entire freeze event. For additional information click here.

- Always remember to remove cold protection once the temperature rises so that the trees do not overheat

- Do not cover trees with plastic tarps, these will not protect the tree and can “cook” the tree once temperatures rise.

Please see the following publications by retired UF / IFAS Extension agents Theresa Friday and David Marshall for additional information regarding freeze protection of citrus.