by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2017

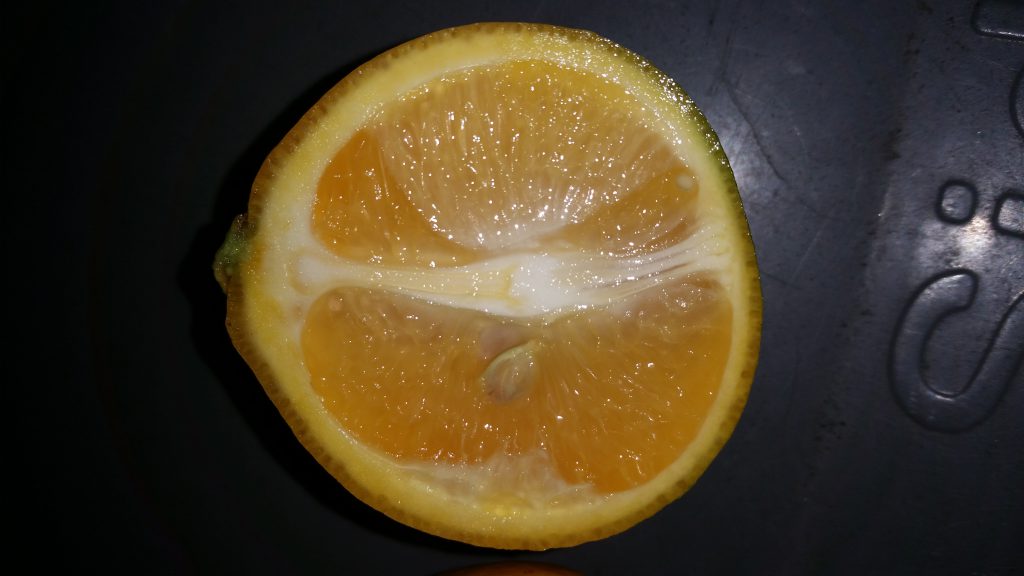

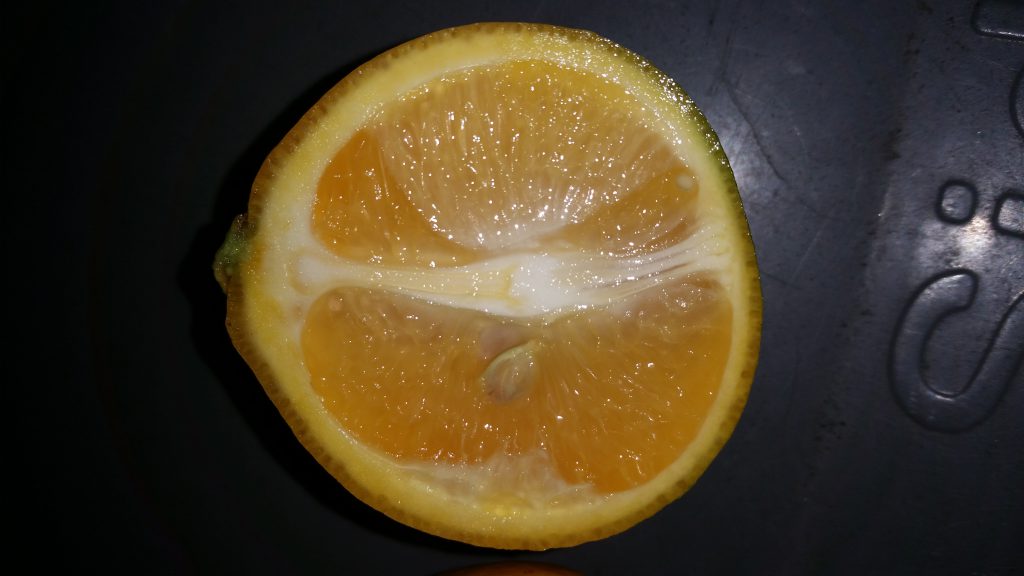

Small Fruit vs Normal

If we look at the big picture when it comes to invasive species, some of the smallest organisms on the planet should pop right into focus. A microscopic bacterium named Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus, the cause of Citrus Greening (HLB), has devastated the citrus industry worldwide. This tiny creature lives and multiplies within the phloem tissue of susceptible plants. From the leaves to the roots, damage is caused by an interruption in the flow of food produced through photosynthesis. Infected trees show a significant reduction in root mass even before the canopy thins dramatically. The leaves eventually exhibit a blotchy, yellow mottle that usually looks different from the more symmetrical chlorotic pattern caused by soil nutrient deficiencies.

One of the primary vectors for the spread of HLB is an insect called the Asian citrus psyllid. These insects feed by sucking juices from the plant tissues and can then transfer bacteria from one tree to another. HLB has been spread through the use of infected bud wood during grafting operations also. One of the challenges with battling this invasive bacterium is that plants don’t generally show noticeable symptoms for perhaps 3 years or even longer. As you would guess, if the psyllids are present they will be spreading the disease during this time. Strategies to combat the impacts of this industry-crippling disease have involved spraying to reduce the psyllid population, actual tree removal and replacement with healthy trees, and cooperative efforts between growers in citrus producing areas. You can imagine that if you were trying to manage this issue and your neighbor grower was not, long-term effectiveness of your efforts would be much diminished. Production costs to fight citrus greening in Florida have increased by 107% over the past 10 years and 20% of the citrus producing land in the state has been abandoned for citrus.

Classic blotchy mottle in Leaves

Many scientists and citrus lovers had hopes at one time that the Florida Panhandle would be protected by our cooler climate, but HLB has now been confirmed in more than one location in backyard trees in Franklin County. The presence of an established population of psyllids has yet to be determined, as there is a possibility infected trees were brought in.

A team of plant pathologists, entomologists, and horticulturists at the University of Florida’s centers in Quincy and Lake Alfred and extension agents in the panhandle are now considering this new finding of HLB to help devise the most effective management strategies to combat this tiny invader in North Florida. With no silver-bullet-cure in sight, cooperative efforts by those affected are the best management practice for all concerned. Vigilance is also important. If you want to learn more about HLB and other invasive species contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

Asymmetrical Fruit

Typical nutrient deficiencies observed in leaf, on trees with heavy fruit load. Not related to Citrus Greening (HLB)

Article by: Erik Lovestrand, UF/IFAS Franklin County Extension Director/Florida Sea Grant Agent

by Ray Bodrey | Jul 5, 2016

It’s safe to say that almost everyone equates citrus with the state of Florida. It just goes hand in hand. Most people first think of citrus as being oranges and grapefruit. Even by traveling south on I-75 or I-95, our welcome centers will gladly supply you with a complimentary cup of the juice of your choice, orange or grapefruit. However, the kumquat is a fruit that rarely comes to mind. The Panhandle is prime habitat for this forgotten fruit.

The kumquat is a native of southeast China, but it has found a home on the Gulf coast. It’s a cold hardy citrus, much like the Panhandle favorite satsuma orange. Due to the plants ability to be semi-dormant in the region, the kumquat has been known to withstand temperatures in the low teens. The kumquat fruit is an oddity in the citrus world. The peeling is sweet, the pulp is tart and it’s all edible, except for the seeds of course. The fruit reaches maturity around October, and will remain viable on the tree until March.

Figure 1: Kumquat fruit: Nagami variety.

Credit: UF/IFAS.

There are two varieties grown in Florida. The Nagami (Fortunella margarita) is by far the most popular in the state. This variety has oval shaped fruit and 2-5 seeds. The Meiwa (Fortunella crassifolia) has a more rounded shaped fruit with almost no seeds. This variety’s fruit is more sweet and juicy compared to the Nagami.

Kumquat is one of the easiest fruits to grow in the Panhandle. Most gardeners enjoy the ease of management as the kumquat tree is relatively small in size, and requires much less care compared to other citrus. Another advantage to kumquats is the ability to be grown in containers. Also, the dark green leaves and orange colored fruit is quite appealing on your back deck or patio.

When planting a kumquat, make sure the location has plenty of sunshine. Always apply mulch, but be sure to keep the mulch at least a foot from the trunk to combat any potential of disease. As for container growing, be sure to purchase a large container with adequate drainage holes. Place a screen in the bottom of the container, rather than rocks. This will ensure no soil is lost during drainage events. Newly planted kumquats will need significant water on a regular basis to become established, especially if planted in a container. Once established, watering can be limited.

Kumquats will need a fertilizer regimen too. A citrus formulated fertilizer works great. Although not required, pruning should be done after April or later in the summer before new flowers appear. A major plus, kumquat trees generally bear fruit just after a couple of years.

Kumquats are a delight to grow in the Panhandle and a fantastic evergreen for your landscape, back deck or patio.

Supporting information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Fortunella spp., Kumquat” by Michael G. Andreu, Melissa H. Friedman, and Robert J. Northrop & “Get Acquainted with Kumquat” by BJ Jarvis, CED & Horticultural Agent, UF/IFAS Pasco County Extension:

by Mark Tancig | Jul 5, 2016

When you don’t know what’s ailing your plant, ask an expert.

Many gardeners get stumped when a favorite plant of theirs comes down with a strange “something”. Many of these gardeners know about UF/IFAS Extension and call their local horticulture and agriculture agents for assistance in figuring out what’s going on. However, even these experts are often stumped by what they see. Fortunately, the agents have another layer of experts to fall back on. In addition to the resources in Gainesville, we have the Plant Disease Diagnostic Clinic, located at the North Florida Research Center in Quincy. Plant pathologists here can help determine what fungus, bacteria, virus, or viroid may be the problem.

Plant pathologists are basically plant doctors. They use all sorts of sophisticated techniques to determine what is the cause of a particular plant problem, from growing out fungal spores to examining DNA. Not only do these plant doctors tell us what the ailment is, they also provide recommended cures, or control options. They are also doing research to prevent different diseases from taking hold in our area and reduce the impact on our local growers.

Plant pathologist at work!

At a recent workshop in Quincy, we learned that plant pathology researchers are working on a fungus that affects watermelons, virus and bacteria that can wipe out a farmer’s tomato crop, and a virus that could impact our local roses. Working as a team of scientists, they study these pathogens in the lab and conduct controlled field experiments to figure out which techniques are most effective. Some of this research is leading to different methods and/or products that can help growers and gardeners alike keep their fields and landscapes healthy.

So, if your plants have problems, please contact your local Extension Office. If they don’t know the answer, then the network of scientists, including plant pathologists, in the UF/IFAS Extension family can be called on for backup to provide you with the best possible answer.

by Mary Salinas | May 5, 2016

The panhandle of Florida is a great place to grow citrus with our plentiful sunshine and sandy soil. But some varieties do better than others. Here are some that thrive in the more northerly climes of Florida:

Nagami kumquat. Photo credit: UF/IFAS.

- Satsuma mandarin is cold hardy to 15°F once established. There are a few different available cultivars with fruit ripening October through December. Fruit needs to be picked promptly when ripe.

- Kumquat is cold hardy to 10°F once established. ‘Nagami’ and ‘Meiwa’ are the two common cultivars of the small tart fruits. Fruit matures in fall and winter and holds fairly well on the trees.

- Calamondin is a lesser known variety that bears small fruit that resemble tangerines. The tart fruit is great for jams and chutneys. Fruit is borne all year.

- Some of the sweet oranges that do well in the panhandle are Navel, Hamlin and Parson Brown. They are cold hardy to 14°F once established and are harvested November through January.

- Minneola or Honeybell tangelo is also hardy to 14°F and harvested in January. This is a cross between a Duncan grapefruit and a Darcy tangerine. This bell-shaped fruit is very juicy and sweet. Unlike the other citrus varieties, it needs another citrus nearby for cross-pollination in order to produce an abundant crop.

- Meyer Lemon is the choice to make if you would like to grow lemons in the panhandle. Other lemons may be damaged by our occasional freezes.

Grapefruit and lime can be grown – although unreliably – on the coast with protection from northwestern winter winds. They are much more susceptible to freezes in more northerly panhandle locations.

In order to have the healthiest and most productive trees, learn about how to properly care for citrus and how to recognize and combat the pests and diseases that occur.

Citrus canker symptoms on leaves, fruit and stem. Photo by Timothy Schubert, FDACS

There are threats to our dooryard and commercial citrus from pests and disease. Only vigilance will help to combat the challenges so that we may continue to grow and enjoy our citrus. What can we do to protect our citrus?

- Report any serious diseases like suspected citrus canker or citrus greening to the Division of Plant Industry by calling toll-free 1-888-397-1517. Inspections and diagnosis are free. Citrus canker has been confirmed in south Santa Rosa County in the past 3 years.

- Purchase citrus trees only from registered nurseries – they may cost a little more but they have gone through an extensive process to remain disease and pest free. That will save you $$ in the long run!

- Don’t bring plants or fruit back into Florida – they may be harboring a pest!

- Citrus trees or fruit cannot move in or out of the State of Florida without a permit. This applies to homeowners as well as to the industry. This rule protects our vital dooryard trees and citrus industry.

For more information please see:

Save Our Citrus Website

UF IFAS Gardening Solutions: Citrus

Citrus Culture in the Home Landscape

UF IFAS Extension Online Guide to Citrus Diseases

Your Florida Dooryard Citrus Guide – Common Pests, Disease and Disorders of Dooryard Citrus

by Mary Salinas | Feb 16, 2016

As you have read in other articles in this blog, it is too early to fertilize your lawn; however, this is a good time to start fertilizing your citrus to ensure a healthy fruit crop later in the year.

Orange grove at the University of Florida. UF/IFAS photo by Tara Piasio.

Citrus benefits from regular fertilization with a good quality balanced citrus fertilizer that also contains micronutrients. A balanced fertilizer has equal amounts of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium such as a 6-6-6, 8-8-8 or a 10-10-10. The amount of fertilizer to be applied will vary on the formulation; for example you will need less of a 10-10-10 than a 6-6-6 as the product is more concentrated. Always consult the product label for the correct amount to use for your particular trees. Fertilizer spikes are not recommended as the nutrients are concentrated in small areas and not able to be widely available to all plant roots.

The number of fertilizations per year will vary depending on the age of the tree. Trees planted the first year need 6 light fertilizations that year starting in February with the last application in October. In following years, decrease the number of fertilizations by one per year until the fifth year when it is down to 3 fertilizations per year. From then on, keep fertilizing 3 times per year for the life of the tree. Good quality citrus fertilizer will have accurate and specific instructions on the label for the amount and timing of fertilizer application.

Fertilizer should be spread evenly under the tree but not in contact with the trunk of the tree. Ideally, the area under the drip line of the tree should be free of grass, weeds and mulch in order for rain, irrigation and fertilizer to reach the roots of the tree and provide air movement around the base of the trunk.

If you have not in recent years, obtain a soil test from your local extension office. This can detect nutrient deficiencies, which may be corrected with additional targeted nutrient applications.

For more information:

Citrus Culture in the Landscape