by Donna Arnold | Feb 19, 2025

Growing pansies in North Florida is a rewarding experience, as these resilient flowers thrive in cooler temperatures. As I walked up to our front office after the ice had melted away, I was amazed to see their vibrant blooms still standing strong, displaying their cheerful faces despite the harsh conditions of the January 2025 winter storm. Their endurance is a testament to their hardiness, making them a perfect choice for winter gardens. Here’s a guide to help you successfully cultivate pansies in our region.

Growing pansies in North Florida is a rewarding experience, as these resilient flowers thrive in cooler temperatures. As I walked up to our front office after the ice had melted away, I was amazed to see their vibrant blooms still standing strong, displaying their cheerful faces despite the harsh conditions of the January 2025 winter storm. Their endurance is a testament to their hardiness, making them a perfect choice for winter gardens. Here’s a guide to help you successfully cultivate pansies in our region.

Best Planting Time

Pansies thrive in cooler weather, making fall (October–November) the ideal time to plant them. Once established, they will provide stunning blooms throughout the winter and into early spring. While they can tolerate mild frosts, Florida’s summer heat is too intense for them, so they are best treated as a seasonal flower.

Choosing the Right Variety

Not all pansies are well-suited for Florida’s fluctuating temperatures. To ensure a successful and long-lasting display, select heat-tolerant varieties such as Majestic Giants, Matrix, or Delta Series, which are known for their resilience and vibrant blooms.

Not all pansies are well-suited for Florida’s fluctuating temperatures. To ensure a successful and long-lasting display, select heat-tolerant varieties such as Majestic Giants, Matrix, or Delta Series, which are known for their resilience and vibrant blooms.

Delta Series – A popular choice for its bold yellow, purple, and blue flowers. This variety is highly valued for its disease resistance, vigorous growth, and ability to withstand both cold and mild heat.

Majestic Giants – A classic pansy cultivar known for its large, eye-catching blooms in a variety of colors and patterns. These compact plants thrive in both container gardens and mass plantings.

Matrix Series – This variety produces dense, bushy plants with large flowers, making it an excellent choice for creating colorful, impactful displays in both garden beds and containers.

By choosing the right variety, you can ensure your pansies thrive throughout the cooler months, bringing beauty and color to your landscape.

Sun and Soil Requirements

For the healthiest plants, provide full sun to partial shade, with at least 4–6 hours of direct sunlight each day. Pansies prefer well-draining soil rich in organic matter, with a slightly acidic to neutral pH (5.5–6.5). Improve your soil’s structure by adding compost or peat moss, which enhances both drainage and nutrient content.

Watering & Care

Maintaining proper moisture levels is key to keeping pansies healthy. Water them 2–3 times a week, ensuring the soil remains moist but not soggy. A layer of mulch will help retain moisture and reduce weed growth. To encourage continuous blooms, apply a balanced, slow-release fertilizer every few weeks and remove spent flowers (deadheading) to keep plants looking fresh and vibrant.

Common Challenges & Solutions

Despite their hardiness, pansies can face a few challenges:

Heat Sensitivity: If temperatures rise unexpectedly, pansies may wilt. Providing afternoon shade can help them cope.

Pests: Keep an eye out for aphids, slugs, and caterpillars. Use insecticidal soap or remove pests by hand to prevent damage.

Fungal Diseases: Avoid overhead watering to prevent root rot and mildew. Ensuring good air circulation will also help reduce disease risks.

Spring Transition

As spring temperatures climb, pansies will naturally begin to decline. To maintain a colorful garden, consider replacing them with heat-tolerant flowers such as zinnias, marigolds, or vincas, which can handle Florida’s warm and humid conditions.

Their cheerful, expressive blooms make them a wonderful choice for adding color and charm to your landscape. Happy planting!

For more information contact your local extension office.

by Gary Knox | Apr 7, 2022

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Imagine walking out your front door with a cup of coffee to admire your garden. A cucumber vine, ripe with crisp, succulent fruit, has grown so large and sprawling that the white staircase handrail is serving as its trellis. The resulting appearance is a lush green entranceway to the front door. The wall of cucumber leaves stands tall behind burgundy-colored day lilies and stokes asters that are shockingly blue. Nearby, buzzing bees feed on fragrant basil flowers. The plum tree planted near the road is heavy with perfectly round reddish-purple fruit that is almost ready to harvest.

Foxtail rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) standing tall in the Dry Garden. Photo Credit: Kelly Thomas – University of Florida/IFAS

You’ve taken up foodscaping, the concept of integrating ornamental plants and edible plants within a traditional landscape. It began during the pandemic with more time spent at home, and the desire to tend to the growth of something. Now, the garden’s bounty has provided groceries, which has proven doubly beneficial as the pandemic continues to disrupt the supply chain and drive up the cost of food.

Brie Arthur sitting on steps next to tomato vines. Photo Credit: Brie Arthur

The concept of foodscaping is not new. In fact, foodscaping has been around in some form or fashion for centuries. In the early 2000’s, Sydney Park Brown, now a UF/IFAS emeritus associate professor, published an EDIS document titled ‘Edible Landscaping.’ Brown describes how edible landscaping allows people to create a multi-functional landscape that increases food security, reduces food costs, and provides fun and exercise for the family, along with other benefits. Foodscaping, another term for edible landscaping, really took off as a movement during the 2008 economic recession.

Around that time, a horticulturist named Brie Arthur wanted to grow vegetables to save money on groceries. However, the restrictions placed by her H.O.A. forced her to venture away from a standard vegetable garden. Within six months, Arthur had won ‘Yard of the Year,’ proving that edible plants can also be aesthetically pleasing, especially when incorporated into a landscape design. Now, her one-acre lot in North Carolina provides almost 70% of what she and her husband consume. Her garden produces food year-round, everything from sweet potatoes, garlic, and pumpkins to edible flowers like dahlias. She even grows sesame and barley, or as she calls it, “future-beer.”

Utrecht blue wheat beginning to form seed heads. Photo Credit: Kelly Thomas – University of Florida/IFAS

Brie Arthur is a charismatic speaker and bestselling author. She continues to be a major proponent of the foodscape movement, inspiring others to realize their landscape’s full potential. Arthur came and gave an energetic and action-packed presentation on foodscaping at UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) in Quincy, FL on March 5th, 2022. Before the workshop, which was titled ‘A New Era in Foodscaping’ adjourned, participants toured edible displays in Gardens of the Big Bend (GBB), a botanical garden located at the UF/IFAS NFREC. Tour participants walked by golden and red-colored amaranth plants bordered by carrots in the Discovery Garden. Waist-high rosemary plants held their own next to agaves and other desert giants in the Dry Garden.

For more information and advice on foodscaping, check out Brie’s YouTube channel, Brie the Plant Lady. Photos of her garden in North Carolina can be found on her blog. University of Florida resources on edible landscaping/foodscaping can be found via EDIS. And come visit Gardens of the Big Bend in Quincy to view edible garden displays in person!

by Ray Bodrey | Feb 25, 2021

Bananas are a great choice for your landscape, whether as an edible fruit producer or simply as an ornamental, giving your space a tropical vibe.

Bananas are native to southeast Asia, however, grow well across Florida. Complementary plants that can be paired with bananas in the landscape are bird of paradise (banana relative), canna lily, cone ginger, philodendron, coontie, and palmetto palm, just to name some.

Bananas are very easy to manage during the warmer months. Bananas are water loving, and that’s putting it lightly. Planting in vicinity of an eave on your home is a good measure for site suitability. Roof rainwater will drastically increase the growth of the banana tree and decrease the need for supplemental irrigation. Banana trees will need full sun and high organic moist soils create the best environment. For nutrition, a seasonal one-pound application of 6-2-12 fertilizer is a good practice to sustain older trees. Young trees should be fertilized every two months for the first year at a rate of a half-pound.

Musa basjoo is one of the most cold hardy banana varieties. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS Extension

If there is a con to banana trees, it’s their cold hardiness. Some varieties fair well and others some not so much. ‘Dwarf Cavendish’ (Musa acuminate) is a popular variety that is found in many garden centers in the state. It produces fruit very well, but it is not very cold hardy. ‘Pink Velvet’ (Musa velutina) produces fruit with a bright pink peel, but isn’t very cold hardy either. A couple of cold hardy ornamental varieties are the ‘Japanese Fiber’ (Musa basjoo) and ‘Black Thai’ (Musa balbisiana), which is by far the most cold hardy, with the ability to easily combat below freezing temperatures.

Freeze damage on a banana tree. Photo Credit: Ray Bodrey, University of Florida Extension – Gulf County

Regardless of cold hardiness, in many cases, banana trees will turn brown after freezing temperatures occur or even if the temperatures reach just above the freezing mark, but will bounce back in the spring. Until then, it’s important not to prune away the brown leaves or trunk skin. These leaves act as an insulator and help defend against freezing temperatures. Usually, the last freezing temperatures that may occur in the Panhandle are around the first of April. So, to be safe, pruning can begin by mid to late April. When pruning, be sure to be equipped with a sharp knife, gloves and work clothes. Banana trunk skin and leaves can be quite fibrous and the liquid from the tree can stain clothing and hands.

So, what’s the best variety of fruiting bananas? Most ornamental bananas do not produce tasty fruit. If you are looking for a production banana, ‘Lady Finger’, ‘Apple’, and ‘Ice Cream’ are popular varieties, but are better suited for the central and southern parts of the state.

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

Supporting information for this article can be found on the UF/IFAS Gardening Solutions website.

Also, for more information see the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “Banana Growing in the Florida Home Landscape”, by Jonathan H. Crane and Carlos F. Balerdi.

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Matt Lollar | Dec 10, 2019

Loquat trees provide nice fall color with creamy yellow buds and white flowers on their long terminal panicles. These small (20 to 35 ft. tall) evergreen trees are native to China and first appeared in Southern landscapes in the late 19th Century. They are grown commercially in subtropical and Mediterranean areas of the world and small production acreage can be found in California. They are cold tolerant down to temperatures of 8 degrees Fahrenheit, but they will drop their flowers or fruit if temperatures dip below 27 degrees Fahrenheit.

A beautiful loquat specimen at the UF/IFAS Extension at Santa Rosa County. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Leaves – The leaf configuration on loquat trees is classified as whorled. The leaf shape is lanceolate and the color is dark green with a nice soft brown surface underneath. These features help give the trees their tropical appearance.

Flowers – 30 to 100 flowers can be present on each terminal panicle. Individual flowers are roughly half an inch in diameter and have white petals.

Fruit – What surprises most people is that loquats are more closely related to apples and peaches than any tropical fruit. Fruit are classified as pomes and appear in clusters ranging from 4 to 30 depending on variety and fruit size. They are rounded to ovate in shape and are usually between 1.5 and 3 inches in length. Fruit are light yellow to orange in color and contain one to many seeds.

A cluster of loquat flowers/buds being pollinated by a honey bee. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS – Santa Rosa County

Propagation – Loquat trees are easily propagated by seed, as you will notice as soon as your tree first bears fruit. Seedlings pop up throughout yards containing even just one loquat tree. It is important to note that the trees do not come true from seed and they go through a 6- to 8-year juvenile period before flowering and fruiting. Propagation by cuttings or air layering is more difficult but rewarding, because vegitatively-propagated trees bear fruit within two years of planting. Sometimes mature trees are top-worked (grafted at the terminal ends of branches) to produce a more desirable fruit cultivar.

Loquat trees are hardy, provide an aesthetic focal point to the landscape, and produce a tasty fruit. For more information on growing loquats and a comprehensive list of cultivars, please visit the UF EDIS Publication: Loquat Growing in the Florida Home Landscape.

by Matt Lollar | Apr 9, 2019

Twisted and tangled kiwifruit plants in a North Florida orchard. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

When we think of kiwis, we think of fuzzy, slightly tart, egg-shaped fruits from somewhere in the Southern Hemisphere. However, there is a species (Actinidia chinensis) of kiwi with smooth skin, sweet taste, and golden color.

Commonly available cultivars of this species are ‘AU Golden Dragon’ and ‘AU Golden Sunshine’. Most years, kiwis won’t produce much of a crop in North Florida because they won’t receive enough chill hours, but they might be fun to try for the adventurous gardener.

- Site Selection – Kiwis perform best in well-drained soils with a neutral pH (around 7.0). High winds may cause canes to break and scar fruit, so a windbreak is recommended or they can be planted near a structure.

- Irrigation – Kiwis need a lot of water during the summer. This is partly due the their large leaves that transpire rapidly because of surface area. Newly planted kiwis should be watered deeply at least once a week.

- Fertilization – Fertilize kiwis three times a year (January, April, and June). Do not apply fertilizer after the month of July to reduce the incidence of cold injury in the winter.

- Insects and Diseases – The most common insects of kiwis are mites and scales. To reduce the incidence of disease, plant kiwis at least 15 feet apart and train on a trellis.

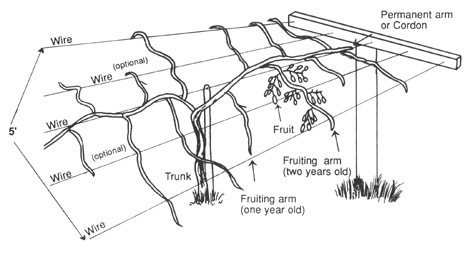

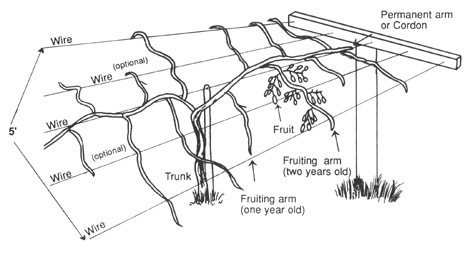

- Training – A T-bar trellis, similar to the system used to train grape vines, or a pergola should be used to provide support for the plants. Once the plants are established (2 to 3 years after planting), about a third of the vines should be removed each year.

An illustration of a T-bar trellis system. University of Georgia Extension

Kiwis are wind- and insect-pollinated. Good growing conditions and insect pollination help increase fruit size. Male and female plants are required for good fruit yields. At least one male (pollen producing) plant should be planted for every four female (fruit producing) plants.

Kiwi plants will soon be planted for evaluation at the West Florida Research and Education Center in Jay, FL. Please stay tuned for future data! For more information on growing kiwis in the Southeast, please visit these webpages:

Kiwifruit Production Guide

Bringing Home the Gold – Auburn horticulture alum gets kiwifruit orchard off the ground in Reeltown

Growing pansies in North Florida is a rewarding experience, as these resilient flowers thrive in cooler temperatures. As I walked up to our front office after the ice had melted away, I was amazed to see their vibrant blooms still standing strong, displaying their cheerful faces despite the harsh conditions of the January 2025 winter storm. Their endurance is a testament to their hardiness, making them a perfect choice for winter gardens. Here’s a guide to help you successfully cultivate pansies in our region.

Growing pansies in North Florida is a rewarding experience, as these resilient flowers thrive in cooler temperatures. As I walked up to our front office after the ice had melted away, I was amazed to see their vibrant blooms still standing strong, displaying their cheerful faces despite the harsh conditions of the January 2025 winter storm. Their endurance is a testament to their hardiness, making them a perfect choice for winter gardens. Here’s a guide to help you successfully cultivate pansies in our region. Not all pansies are well-suited for Florida’s fluctuating temperatures. To ensure a successful and long-lasting display, select heat-tolerant varieties such as Majestic Giants, Matrix, or Delta Series, which are known for their resilience and vibrant blooms.

Not all pansies are well-suited for Florida’s fluctuating temperatures. To ensure a successful and long-lasting display, select heat-tolerant varieties such as Majestic Giants, Matrix, or Delta Series, which are known for their resilience and vibrant blooms.

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center

Written by: Kelly Thomas – Agricultural/Food Scientist II with the University of Florida/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center