by Larry Williams | Jun 5, 2024

The widespread multiple night hard freeze that occurred in North Florida near the end of December 2022 resulted in numerous citrus trees becoming severely damaged. The above ground portion of many of these trees died as a result of the extreme cold.

I talked with numerous homeowners who were concerned about their citrus trees following that weather event. Many of these homeowners earnestly and hopefully watched for any sign of new growth on their cold injured citrus trees the following spring. When new growth appeared from the lower portion of the trunk and from the roots, the homeowner became excited with a false sense of hope that their citrus tree had survived and would again produce an abundance of desirable fruit.

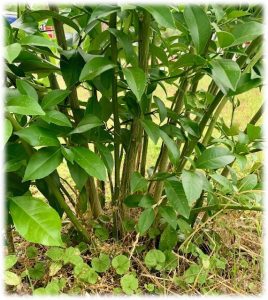

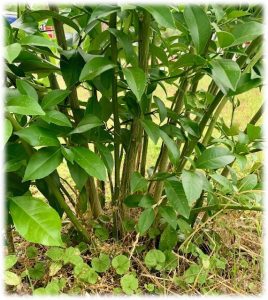

Cold injured citrus tree with new growth coming from rootstock. Credit: Larry Williams

Now in the spring of 2024, many of these citrus trees have somewhat regrown from those root shoots, not from the completely dead tops. In most cases, the freeze damaged, dead tops of the once large trees have now been pruned away to allow the multitude of small diameter vigorous green shoots to grow.

Most purchased citrus trees are grafted. So, what survived and is now regrowing is coming from the rootstock, not from the original, desirable, edible fruit producing top. That desirable top was completely killed.

To better understand this scenario, perhaps a basic definition of grafting will help. This definition was taken from a University of Missouri Extension publication on grafting. “Grafting is the act of joining two plants together. The upper part of the graft (the scion) becomes the top of the plant, the lower portion (the understock) becomes the root system or part of the trunk.” Understock is also known as rootstock.

Grafting involves joining two different individuals. These individuals have to be closely related. For example, citrus can be grafted to other types of citrus and peaches can be grafted to other types of peaches. But citrus cannot be grafted to peaches.

The rootstock was selected because of some beneficial trait(s): resistant to a root pest, superior cold hardiness, imparts a dwarf growth habit to the top, etc. But the same rootstock produces undesirable fruit: bitter, hard, extremely seedy, etc. The top (scion) was selected because of a superior fruit: sweeter, bigger, more disease resistant, etc. But the same scion produces an inferior/weak root system. So, grafting the two together allows for the “best of both worlds.”

When all that is left is originating at or below the graft union or rootstock, the eventual resulting fruit will usually be undesirable, sometimes not edible.

So unfortunately, the best option in this scenario is to start over with another healthy grafted tree that is well suited for the potential cold weather of extreme North Florida.

by Julie McConnell | May 30, 2024

The value of tomatoes produced in Florida in 2022 was $323,000,000 according to the USDA National Agricultural Statistics Survey and sometimes I feel like I’ll spend that much trying to get one perfect tomato in my garden. Nothing beats the taste of a fresh homegrown tomato, but unfortunately, they are susceptible to a wide host of diseases, insects, and even nematodes making them a challenge for even the most seasoned gardener.

Some of these pests can be tolerated without too much reduced yield, while others warrant removal of the plant to prevent further spread. Over the past couple of weeks, we have received a lot of calls about tomato plants that look normal and full of fruit one day then wilt despite plenty of available water. This symptom can be caused by a litany of ailments but when you also notice stem discoloration and perform the bacterial ooze test it is a pretty strong indicator that the cause may be bacterial wilt*.

The bacterial ooze test is simply taking a freshly cut stem of a symptomatic plant and placing it cut-side down into a glass of water (can be plastic but must be transparent) and watching for bacterial streaming. This will look like ribbons of goo coming out of the stem – that is not a technical term, but when you see it, you know it.

Bacterial wilt caused by Ralstonia solanacearum (Previously Pseudomonas solanacearum) affects over 200 species of plants. There are many strains including those affecting tomato, potato, and eggplant – all members of the nightshade family and commonly grown plants. If infected plant material is in the garden, it can spread to susceptible plants through wounds in roots or stems, nematode feeding, contaminated irrigation water, infected weeds, pruning equipment, and surface runoff. The pathogen can also remain viable in the soil for years, requiring well-planned crop rotation practices.

There is no cure and the best a gardener can do is spot it early and use good sanitation practices and crop rotation to minimize spread. For more information on this disease visit https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/rsol/Trainingmodules/RalstoniaR3b2_Sptms_Module.html

Visit U-scout Tomato Diseases to view common tomato disease symptoms https://plantpath.ifas.ufl.edu/u-scout/tomato/index.html

*Please note that symptom observation and bacterial streaming tests do not constitute a definitive diagnosis and lab analysis is recommended for commercial producers.

Streams of bacterial ooze began about 5 minutes after placing tomato stem in water. Photo: J. McConnell, UFIFAS

Symptoms of tomato bacterial wilt worsen during fruit ripening. Photo: J. McConnell, UFIFAS

by Carrie Stevenson | May 30, 2024

During rainstorms, pollutants from yards and roads are picked up and flow downstream. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In most Florida waterways, stormwater runoff is the primary source of pollution. If you think about what gets washed down the drain during a typical rainstorm, it may include anything from trash and construction dirt to oils, gasoline, and chemicals from surrounding lawns.

A lawn care professional reading the safety and instruction labels of agriculture-based pesticides and fertilizers. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS

Pesticides were first regulated at a national level in 1947, with the passing of the Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (FIFRA). In the early 1970’s, more regulations were put in place at national and state levels. There are specific instructions for use on every bag of insecticide or fungicide sold—a concept we refer to as, “the label is the law”—which homeowners are bound to follow if using own their own yard. But if someone has a professional business where they apply pesticides to yards, golf courses, or other athletic fields, they must have a license to do so. These pesticide licenses vary by type of application and landscape, but earning one entails participation in training, taking a test, and continuing education to maintain certification.

When used properly, fertilizer can help plants thrive. In excess, fertilizer can contribute to major water quality issues. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS

While the nutrients in fertilizer have long been known to contribute to water quality problems–particularly algae blooms–it was not until 2009 that fertilizer was regulated similarly to pesticides in Florida. As of 10 years ago, the state required horticulture professionals applying fertilizer as part of their services to obtain a separate license. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) provides a certification in Green Industries Best Management Practices (GI-BMP), designed to teach the safest and most effective means of using fertilizer products. Instructional classes are typically taught by Extension Agents or other horticulture professionals, or from a self-paced online program.

Agriculture-based pesticide and fertilizer application personal protective equipment (PPE) including boots, gloves, aprons, goggles, respirators, masks, and a Tyvek suit. Photo credit: Tyler Jones, UF IFAS

To earn the license, individuals may attend a GI-BMP training class, take a test, and if they pass will receive a certification. From there, they fill out a Limited Landscape Commercial Fertilizer Application and send $25 with their certification number to the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Sciences (FDACS) to receive the license. Licenses last four years and must be renewed, a process that includes more continuing education classes.

The GI-BMP courses cover cultural landscape practices, pesticide storage and safety, proper irrigation, and details on fertilizer application. If you are a homeowner hiring a lawn care service, ask about their pesticide and fertilizer licenses. Employing a licensed lawn care professional is not only following the law, but also improves the odds that your lawn will be maintained well and in an environmentally responsible manner.

If you work in this industry and are seeking certification to apply fertilizer, the online classes are available on demand. To see a statewide in-person class schedule, visit the following website: https://gibmp.ifas.ufl.edu/classes.

by Abbey Smith | May 23, 2024

Florida’s diverse ecosystem is home to a variety of native plants that provide resources for local pollinators. Native flowers are not only a beautiful addition to any garden but also play a crucial role in maintaining the health of our environment. Planting native species supports the delicate balance of local ecosystems and promotes the survival of native pollinators, such as bees, butterflies, and hummingbirds. Here are some native Florida flowers that are perfect for attracting and sustaining native pollinators.

Coreopsis (Coreopsis spp.)

October 2008 IFAS Extension Calendar Photo. Corey Yellow Coreopsis, flower. UF/IFAS Photo: Thomas Wright.

Coreopsis, also known as tickseed, is Florida’s state wildflower. These bright, yellow flowers are a favorite among native bees and butterflies. Coreopsis blooms from spring through fall, providing a long-lasting nectar source. They thrive in full sun and well-drained soil, making them an excellent choice for gardens and landscapes across the state.

Black-Eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta)

Rudbeckia hirta Photo Credit: Danielle Williams, UF/IFAS Extension Gadsden County

Black-eyed Susans are easily recognizable by their bright yellow petals and dark brown centers. These hardy perennials attract a variety of pollinators, including bees and butterflies. They are drought-tolerant and prefer full sun, making them a resilient addition to any garden.

Blanket Flower (Gaillardia pulchella)

Photo Credit: Beth Bolles, UF/IFAS Extension Escambia County

Blanket Flower, also known as Firewheel, can be found throughout Florida in dry, sandy soils and sunny conditions. It is also a hardy perennial and is known for its long blooming period from spring to fall. The red and yellow blooms are a perfect pollinator attractant, particularly bees and butterflies.

Purple Coneflower (Echinacea purpurea)

Flowers and insects at the student gardens on the University of Florida campus. Pollinating bee. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones.

Purple coneflowers are not only striking with their large, purple petals and spiky centers but are also magnets for bees and butterflies. The nectar of this flower will attract a variation of bees, butterflies, and some hummingbirds, but the seeds that the coneflower produces can be eaten by wildlife. The purple coneflower is considered an endangered native Florida wildflower and can only be found naturally in Gadsden County.

American beautyberry (Callicarpa americana)

While this is not a “traditional” wildflower, the beautyberry is an important native pollinator plant and food source for wildlife. The flowers are small in size and vary from light pink to lavender in color. The blooms open in late spring/early summer and produce a purple berry that can be an additional food source for birds and other animals.

By choosing to plant native wildflowers, you can create a vibrant and thriving garden or landscape bed that supports Florida’s native pollinators. For more information on Florida’s native wildflowers please visit:

https://www.flawildflowers.org/

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/EP297

https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/topics/wildflowers

by Beth Bolles | May 23, 2024

Scouting is an important part of keeping pests in check and gardeners are often up to the task. As you routinely enjoy the beauty of your ornamental and edible plants, you are likely to catch a pest sighting before it gets out of control. One insect that may trick us upon first glance into thinking we have a pest is an interesting lady beetle called the Mealybug destroyer.

Lady beetles are one of the most recognizable insects in the garden with their rounded shiny bodies and often bright colors and spots. The adult mealybug destroyer is smaller than a typical lady beetle, about 1/8 of an inch long, with a dark brownish black body and dull orangish head. They move quickly over flowers and leaves in search of food. The larval stage can be confusing because immatures look very similar to mealybugs, one of their favorite prey. Larva have white, woolly protuberances on the body. Whereas pest mealybugs look flatter, the mealybug destroyer immatures have parts that look like soft white spikes.

Pest mealybug compared to beneficial mealybug destroyer. Photos by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County.

Why not learn to recognize an insect that eats lots of soft bodied pests on your plants? Once you see one, you will be able to spot these beneficials more often on your favorite garden flowers.

Mealybug destroyer immatures feeding on aphids. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Extension Escambia County