by Daniel J. Leonard | Oct 14, 2020

Article by Jessica Griesheimer & Dr. Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy

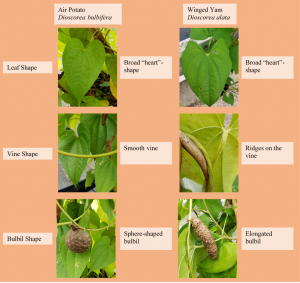

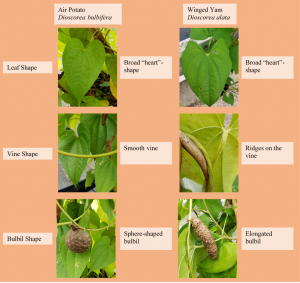

Dioscorea bulbifera, commonly known as the air potato is an invasive species plaguing the southeastern United States. The air potato is a vine plant that grows upward by clinging to other native plants and trees. It propagates with underground tubers and aerial bulbils which fall to the ground and grow a new plant. The aerial bulbils can be spread by moving the plant, causing the bulbils to drop to the ground and tubers can be spread by moving soil where an air potato plant grew prior. The air potato is commonly confused with and mistaken as being Dioscorea alata, the winged yam which is also highly invasive. The plants look very similar at first glance but have subtle differences. Both plants exhibit a “heart”-shaped leaf connected to vines. The vines of the winged yam have easily felt ridges, while the air potato vines are smooth. They also differ in their aerial bulbil shapes, the winged yam has a long, cylinder-shaped bulbil while the air potato aerial bulbil has a rounded, “potato” shape (Fig. 1).

In its native range of Asia and Africa, the air potato has a local biocontrol agent, Lilioceris cheni commonly known as the Chinese air potato beetle (Fig. 2). As an adult, this beetle feeds on older leaves and deposits eggs on younger leaves for the larvae to later feed on. Once the larvae have grown and fed, they drop the ground where they pupate to later emerge as adults, continuing the cycle. The Chinese air potato beetle will not feed on the winged yam, as it is not its host plant.Current methods of air potato plant, bulbil, and tuber removal can be expensive and hard to maintain. The plant is typically sprayed with herbicide or is pulled from the ground, the aerial bulbils are picked from the plant before they drop, and the underground tubers are dug up. The herbicides can disrupt native vegetation, allowing for the air potato to spread further should it survive. If the underground tuber or aerial bulbils are not completely removed, the plant will grow back.

The Chinese air potato beetle is currently being evaluated as a potential integrated pest management (IPM) organism to help mitigate the invasive air potato. The beetle feeds and reproduces solely on the air potato plant, making it a great IPM organism choice. During 2019, we studied the Chinese air potato beetle and its ability to find the air potato plant. It was found the beetles may be using olfactory cues to find the host plant. Further research is conducted at the NFREC to increase natural aggregation of the beetles on air potato to improve biological control of the weed.

Chinese Air Potato Leaf Beetle.

If you have the air potato plant, or suspect you have the air potato plant, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!

by Larry Williams | Oct 1, 2020

Adult cicada on tree branch, Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF Entomologist

“What is that noise,” asked the visitors to Middle Georgia when I was a teenager. They were visiting during the summer from El Paso, Texas. I asked, “What noise?” The reply, “That loud noise in the trees.” I responded, “Oh, those are cicadas.’ There are sounds that are so common that sometimes you quit hearing them.

Before the visitors left for El Paso, I made sure to show them the brown, dry shells (exoskeletons) of cicadas that are not difficult to find attached to the trunk of a Georgia pine tree during summer. Cicadas leave their nymph exoskeletons on the trunks of trees and sometimes shrubs when they shed them to become mature flying adults.

You may not have ever seen a cicada but you’ve undoubtedly heard one if you live in Florida. These insects make a loud buzzing noise during the day in the spring and summer. Male cicadas produce their distinctive calls with drum-like structures called timbals, located on the sides of their abdomens. The sound is mainly a calling song to attract females for mating.

Cicadas spend most of their life underground as nymphs (immature insects) feeding on the sap of roots, including trees, grasses as well as other woody plants. They can live 10 or more years underground as nymphs. In some parts of the United States, there will be news reports of when periodical cicadas are expected to emerge from the ground. Periodical cicada species mature into adults in the same year, usually on 13- or 17-year life cycles. Their numbers can be enormous as they emerge, gaining much local attention. However, cicada species in Florida emerge every year from late spring through fall and in much smaller numbers as compared to the periodical cicadas.

Cicada emerging from exoskeleton, Photo credit: Lyle Buss, UF Entomologist

There are at least nineteen species of cicadas in Florida, ranging from less than a ¼ inch to over 2 inches in length. Some people might be frightened by their size and sounds but thankfully cicadas don’t sting or bite. They are a food source for wildlife, including some bird species and mammals.

Very rarely, I’ll have someone ask about small twigs from trees found on the ground as a result of the female cicada’s egg-laying process. But because this is usually such a minor issue with practically no permanent damage to any tree, cicadas really aren’t considered to be a pest of any significance in Florida.

For more information on cicadas, contact the University of Florida Extension Office in your County. Or visit the following UF/IFAS web page. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in602

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 28, 2020

2020 has not been the most pleasant year in many ways. However, one positive experience I’ve had in my raised bed vegetable garden has been the use of a cover crop, Buckwheat (Fagopyrum esculentum)! Use of cover crops, a catch-all term for many species of plants used to “cover” field soil during fallow periods, became popular in agriculture over the last century as a method to protect and build soil in response to the massive wind erosion and cropland degradation event of the 1930s, the Dust Bowl. While wind erosion isn’t a big issue in raised bed gardens, cover crops, like Buckwheat, offer many other services to gardeners:

Buckwheat in flower behind summer squash. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

- Covers, like Buckwheat, provide valuable weed control by shading out the competition. Even after termination (the cutting down or otherwise killing of the cover crop plants and letting them decompose back into the soil as a mulch), Buckwheat continues to keep weeds away, like pinestraw in your landscape.

- Cover crops also build soil. This summer, I noticed that my raised beds didn’t “sink” as much as normal. In fact, I actually gained a little nutrient-rich organic matter! By having the Buckwheat shade the soil and then compost back into it, I mostly avoided the phenomena that causes soils high in organic matter, particularly ones exposed to the sun, to disappear over time due to breakdown by microorganisms.

- Many cover crops are awesome attractors of pollinators and beneficial insects. At any given time while my Buckwheat cover was flowering, I could spot several wasp species, various bees, flies, moths, true bugs, and even a butterfly or two hovering around the tiny white flowers sipping nectar.

- Covers are a lot prettier than bare soil and weeds! Where I would normally just have either exposed black compost or a healthy weed population to gaze upon, Buckwheat provided a quick bright green color blast that then became covered with non-stop white flowers. I’ll take that over bare soil any day.

Buckwheat cover before termination (left) and after (right) interplanted with Eggplant. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard, UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension.

Now that I’ve convinced you of Buckwheat’s raised bed cover crop merits, let’s talk technical and learn how and when to grow it. Buckwheat seed is easily found and can be bought in nearly any quantity. I bought a one-pound bag online from Johnny’s Selected Seeds for my raised beds, but you can also purchase larger sizes up to 50 lb bags if you have a large area to cover. Buckwheat seed germinates quickly as soon as nights are warmer than 50 degrees F and can be cropped continuously until frost strikes in the fall. A general seeding rate of 2 or 3 lbs/1000 square feet (enough to cover about thirty 4’x8’ raised beds, it goes a long way!) will generate a thick cover. Simply extrapolate this out to 50-80 lbs/acre for larger garden sites. I scattered seeds over the top of my beds at the above rate and covered lightly with garden soil and obtained good results. Unlike other cover crops (I’m looking at you Crimson Clover) Buckwheat is very tolerant of imperfect planting depths. If you plant a little deep, it will generally still come up. A bonus, no additional fertilizer is required to grow a Buckwheat cover in the garden, the leftover nutrients from the previous vegetable crop will normally be sufficient!

Buckwheat “mulch” after termination. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard, UF/IFAS Calhoun County Extension.

Past the usual cover crop benefits, the thing that makes Buckwheat stand out among its peers as a garden cover is its extremely rapid growth and short life span. From seed sowing to termination, a Buckwheat cover is only in the garden for 4-8 weeks, depending on what you want to use it for. After four weeks, you’ll have a quick, thick cover and subsequent mulch once terminated. After eight weeks or so, you’ll realize the plant’s full flowering and beneficial/pollinator insect attracting potential. This lends great flexibility as to when it can be planted. Have your winter greens quit on you but you’re not quite ready to set out tomatoes? Plant a quick Buckwheat cover! Yellow squash wilting in the heat of summer but it’s not quite time yet for the fall garden? Plant a Buckwheat cover and tend it the rest of the summer! Followed spacing guidelines and only planted three Eggplant transplants in a 4’x8’ raised bed and have lots of open space for weeds to grow until the Eggplant fills in? Plant a Buckwheat cover and terminate before it begins to compete with the Eggplant!

If a soil building, weed suppressing, beneficial insect attracting, gorgeous cover crop for those fallow garden spots sounds like something you might like, plant a little Buckwheat! For more information on Buckwheat, cover crops, or any other gardening topic, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Happy Gardening!

by Sheila Dunning | Aug 31, 2020

Photo from USDA APHIS

Remember last year’s vacation trip? You picked the perfect location, checked into the hotel and made sure to check every mattress corner for bedbugs. Bugs can hide in the strangest places. Now with COVID-19 those people insisting on still taking a vacation are flocking to Northwest Florida. While some are still utilizing hotels, the majority are pulling into the RV park or campground. They are bringing anything and everything anyone could possibly need for the week, from firewood to camp chairs. That way no one will have to go to the store. Somewhere on the vehicle or within all the stuff there may be some hitchhikers, insect stowaways. The problem is that these bugs may be staying even after the human beings head back north. Florida is notorious for invasive species. With 22 international airports and 15 international ports in the state, hundreds of foreign insects are intercepted each month. But, not all the problem creepy crawlers are coming from the south. Many have been introduced to northern states and work their way here.

One to keep an eye open for is spotted lanternfly (Lycorma delicatula). The Asian native was first detected in Pennsylvania in 2014. Since then it has spread to the east and south. While the insect can walk, jump, or fly short distances, the quickest way for the spotted lanternfly to relocate is to lay eggs on natural and man-made surfaces. Some of those egg masses may fall off and get left at the park. Next spring after the eggs hatch the nymphs will begin feeding on the sap of numerous plants, often changing species as they mature. Host plants include grape, maple, poplar, willow and many fruit tree species.

Nymphs in the early stages of development appear black with white spots and turn to bright red before becoming adults. At maturity spotted lanternflies are about 1 ½ inches wide with large colorful, spotted wings.

Photo from USDA APHIS

At rest their forewings are folded up giving the lanternfly a dull light brown appearance. But when it takes flight its beauty is revealed. The bright red hind wings and the yellow abdomen are very eye-catching. Remember, in nature bright colors are often a warning. Though spotted lanternflies are attractive, they pose a valid threat to native and food-producing plants. The adults feed by sucking sap from branches and leaves. What goes in must come out. Sugar in, sugar out. Spotted lanternflies excrete a sticky, sugar-rich fluid referred to as honeydew. Black sooty mold often develops on honeydew covered surfaces.

Spotted lanternflies are most active at night, steadily migrating up and down the trunk of trees. During the day they tend to gather together at the base of the plants under a canopy of leaves. So, you may need your lantern (or head lamp) to locate them. If you find an insect that you suspect is a spotted lanternfly, please contact your local Extension office of the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services Division of Plant Industries.

Photo by USDA APHIS

by Daniel J. Leonard | Aug 24, 2020

August is awful. Its heat makes one miss the relative cool of July. Its rain is so sporadic that it invokes nostalgia for the rainy afternoons of early summer. But if there is a silver lining in August for gardeners, it is the simplicity that it brings. The weaker spring crops, tomatoes, squash and the rest, are all gone now, destroyed or rendered fruitless by insects, disease, and heat. This leaves only the hardened, usually pest and disease-free survivors Okra, Pepper, Sweet Potato and Eggplant. I say usually because, this year, my eggplant bed is under attack by a new-to-me pest, the False Potato Beetle!

I’ve dealt with Colorado Potato Beetles (CPB) before. Those orangish, black-striped terrors often attack my spring potato crops and occasionally bother early tomatoes. However, I’ve never seen them in late summer on Eggplant. This raised suspicion. Also, I spotted unusual, round, whitish purple creatures munching on leaves from the same plants; these appeared to be the larval stage of the unidentified beetle. A little digging led me to identify these garden pests as the lesser known, lookalike cousin of CPB, the False Potato Beetle.

False Potato Beetle munching on an Eggplant leaf in the author’s garden.

False Potato Beetle (FPB) looks nearly identical to its cousin in the adult stage. They are similarly shaped and colored, though a close look reveals subtle differences between species. While both have yellowish-orange heads and pale-yellow backs with dark stripes, the FPB’s back is slightly lighter hued, more of a whitish, cream color. Also, the CPB’s underside and legs are a very dark orange to brown, with the False Potato Beetle having lighter colored legs and underside. If you’re saying, “These old eyes will never be able to tell the difference, County Agent. Cream and light-yellow look the same to me.”, I get it. Fortunately for those of us with poor vision, the larval stage (babies) of the two beetles looks very different and is the key to correct ID! FPB larvae are larger and have a whitish coloration. CPB larvae, in contrast, are a similar burnt orange color to the adult beetle. I promise, the difference is very distinguishable!

False Potato Beetle is considered a minor garden and agronomic pest as they typically only bother Eggplant, and they don’t usually destroy entire plants. However, if you get a FPB outbreak in your Eggplant garden, they can still be pretty destructive. These beetles feed in the same manner as caterpillar pests, chewing away entire sections of leaves and stems. Unchecked infestations can defoliate entire sections of plants. So, if you find these little beetles eating away at your eggplant garden, what can you do?

False Potato Beetle larvae. Photo courtesy of the author.

First, if you scout regularly, you’ll notice the beetles and their larvae in relatively small numbers before outbreaks become widespread. I had pretty good success this year just catching infestations early and picking off the beetles I saw and squishing them. Continue scouting and squishing for a few days and pretty soon, the population is reduced to a manageable level. However, if squishing makes you squeamish, you also have some common pesticide options at your disposal. I normally encourage clients to start their chemical pest control strategy with “softer” products like Pyganic, a pyrethrin make from an extract from the Chrysanthemum plant. Pyganic works great but is a little harder to find; you may have to order online or ask your local retailer if they can get it for you. If you are unable to find Pyganic or it doesn’t perform for you, the old standby products with carbaryl or pyrethroids (Sevin, Ortho Bug-B-Gone, and others) also work well.

False Potato Beetle can be a late summer garden pain, but with regular scouting, proper insect ID, lots of squishing, and maybe a timely pesticide application or two, you should be able to continue to harvest eggplant deep into fall! If you have FPB in your garden or have another horticultural question, give your local UF/IFAS County Extension office a call! Happy Gardening!