by Rick O'Connor | May 29, 2015

This month there were many more plants flowering… it is true that April showers do bring May flowers. May not only brings more flowers but more tourists. Everyone is out enjoying the weather, including some wildlife. I was happy to include Florida Master Naturalist Paul Bennett on this hike and he was very helpful identifying plants. Thanks Paul!

Tent set up on Pensacola beach to protect from the sun. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Sign altering and educating folks that this is a sea turtle nest. Photo: Rick O’Connor

It is sea turtle nesting season all along the Florida Panhandle. The season begins in May and ends in October. This time of the season the females are heading up the beach looking for good nesting locations near dunes. There are five species of marine turtles that inhabit the northern Gulf and there are records of each species nesting here. They emerge at night and move towards the dunes where they excavate a deep cavity to lay about 100 eggs. The nest is covered and she returns to the water. The incubation period is between 60-70 days and the temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchling; the warmer eggs becoming females. It is illegal to disturb a sea turtle nest.

This tent was occupied when I was there but all too often they are left overnight so folks can return the same spot the following day. Tents and chairs are barriers for both nesting females and emerging hatchlings. If at all possible, remove these for the evening. In some counties it is required. Another problem is artificial lighting. Adult turtles are distracted, and many times abort the nesting activity due to bright lights. Most panhandle counties have a lighting ordinance that requires homes to use turtle friendly lighting. To learn more about the turtle friendly lighting program and local ordinances contact your county Sea Grant Agent at the local Extension office or visit http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/managed/sea-turtles/lighting/.

This county sign marks a public snorkel reef and also educates everyone about lionfish. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Mangrove seed washed ashore. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Summer means swimming and in many local counties there are interesting snorkel reefs nearby. We asked that everyone keep an eye out for the invasive lionfish as they enjoy their day. If one is spotted be aware they do have venomous, though not deadly, spines and please contact your local Sea Grant Agent at the county Extension office to let them know. If you are in Escambia County you can log your sighting at www.lionfishmap.org and FWC has a lionfish app for reporting; http://myfwc.com/news/news-releases/2014/may/28/lionfish-app/

The seed is of a red mangrove tree. These are common coastal plants in south Florida and elsewhere in the tropics. The red mangroves drops their seeds (propagules) into the water to drift in the currents to new locations. They frequently wash upon our shores and sometimes take root, but they do not last during our colder winters.

This Whitlow-Wort, also known as “square flower”. Common dune plant. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Track of an unidentified snake crossing a dune. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The flower to the left is the Whitlow-Wort, or as some locals call it… “square flower”. The track is of a snake but could not find it so I am not sure which species. The weather warms quickly here along the Gulf coast. A few months ago we may have been able to find this animal but with the increasing heat they were in a cool place somewhere. Snake encounters this time of year are typically at dawn and dusk.

The seed pod of a milkweed. Photo: Rick O’Connor

An open seed pod of a milkweed releasing seeds. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The milkweed bloomed a few months ago but here in May we find both the seed pods and, in the photo to the right, the “dandelion-like” seeds being released. This is one of the plants used by the migrating monarchs, which we should see later in the year.

Marsh Pink, a flower found in the wetter areas of the island.

Narrow-leaved Sagittaria. Another water loving plant.

Here are two of the many flowers we saw today. Both of these were found in the freshwater ponds located in the swale areas of the barrier island. The flower to the left is known as Marsh Pink. The one to the right is Narrow-leaved Sagittaria.

The yellow vine called “Love Vine”; correct name is Dodder.

It is good to see bees on the island.

This orange-yellow stringy vine is called “Love Vine” but there is not much love here; this is a parasitic plant called Dodder. This is the first we have seen of it this year and expect to see more. Many residents on the island believe it to be an non-native invasive plant but it is actually a native and quite common out there. I have also seen it in the north end of Escambia County.

We did see a few bees today and this is a good sign. There have been reports in recent years of the decline of our native bees and the impact that has had on gardening and commercial horticulture. In addition to seeing bees Paul and I also came across the famous yellow fly. These were encountered near the marsh on the sound side of the island. Loads of fun there!

The “bed” made by an unknown animal that has been frequenting this location all year. Photo: Rick O’Connor

This scat pile was near the location of the “bed” and along the drag marks made by this animal.

If you have been following this series since we began in January you may recall the strange “bedding” and drag marks we have encountered near the marsh (you can read other issues on this website). I have seen these drag marks, and apparent bedding areas, every month except last. I showed them to Paul and we are still not sure what is making them. Again, whatever it is seems to move from one body of water to another. We cannot find in foot tracks to help identify it… but we will!

The photo to the right is of a large scat pile approximately 15-16” across. It was relatively fresh and contained crab and shrimp shell parts. Not sure if it was left by the same animal that continually makes the drags but was in the same location so…

The pretty, but invasive, beach vitex. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Many of the plants on our barrier islands are blooming now, and so is this one. This is Beach Vitex (Vitex rotundifolia). It is an invasive/not-recommended plant. Currently we are only aware of 22 properties in Escambia County that have it. Sea Grant is currently working with the SEAS program at the University of West Florida to assist in removing them. If you believe you have this plant and would like advice on how to remove contact your local Sea Grant Agent at the county Extension office.

Let’s see what shows up in June!

by Erik Lovestrand | May 29, 2015

![Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/files/2015/05/Schleiden-meduse-2-202x300.jpg)

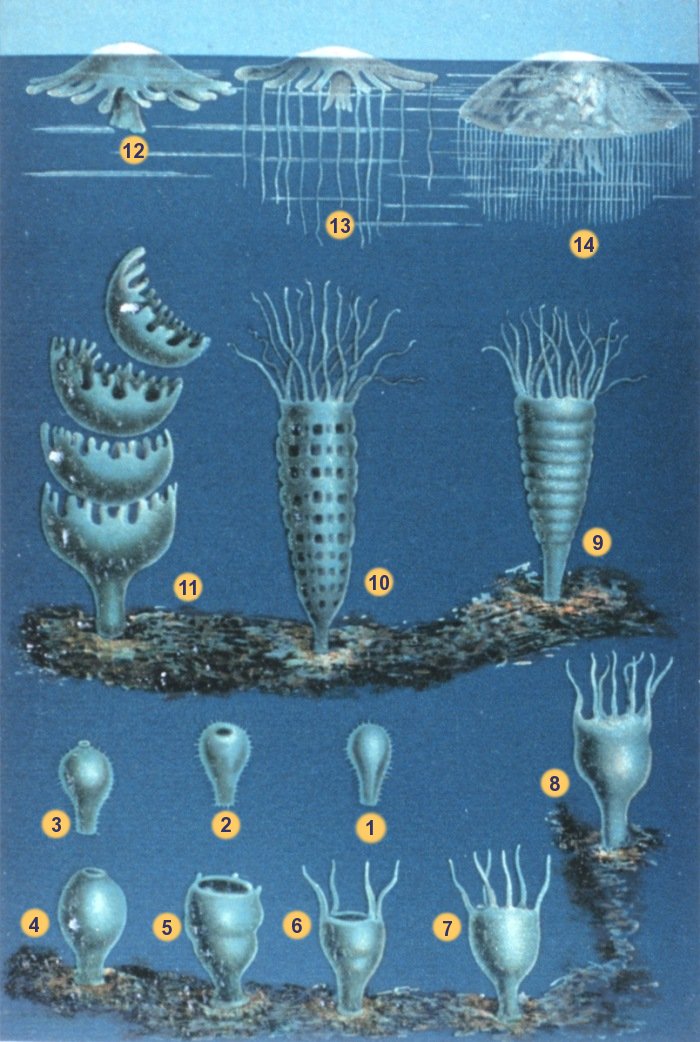

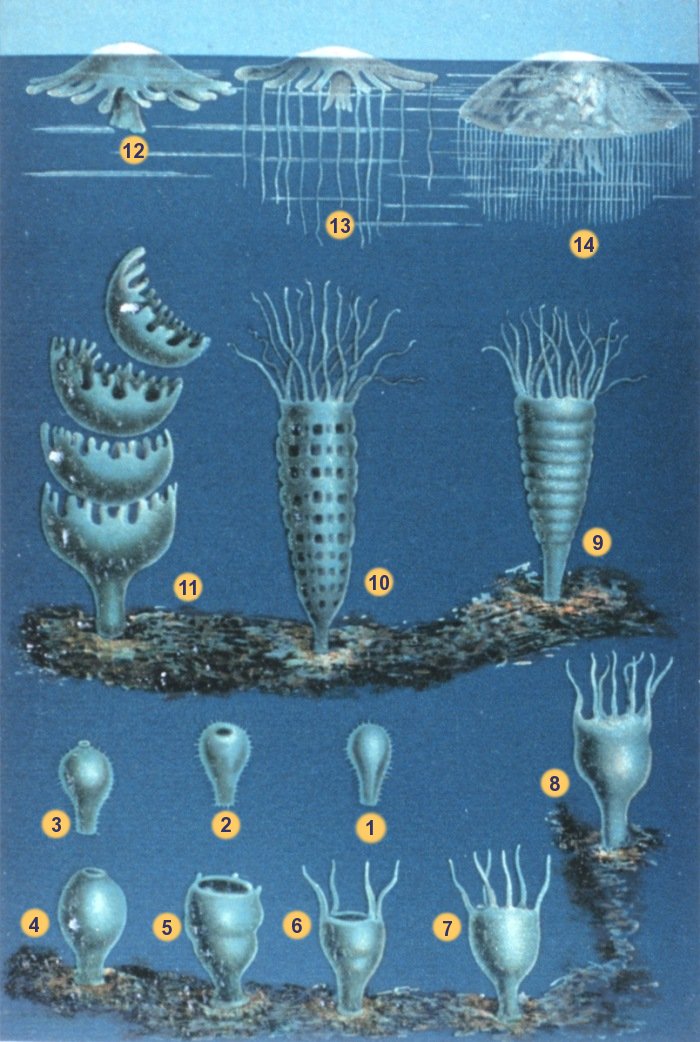

Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

“Ouch, something just stung me.” This is a common phrase to hear someone say (I’ve heard myself say it) while enjoying the otherwise soothing waters along our beautiful Gulf Coast. We host an amazing variety of marine organisms that possess the ability to sting when contacted. I’m referring to organisms in the phylum Cnidaria (pronounced “ni-dair-ee-ah”), which includes about 10,000 species that have been identified. There is general agreement on the classification of five different classes of cnidarians, all of which have stinging cells, but most of which are not dangerous to humans. These include Class Anthozoa (anemones and corals), Class Cubozoa (box jellyfish), Class Scyphozoa (true jellyfish), Class Staurozoa (stalked jellyfish) and Class Hydrozoa (hydroids i.e. Portuguese man o’ war). I’m always intrigued by the origin of scientific names so here is a slight tangent for you on the group names (Cnides: from the greek meaning nettle)(Antho: flower-like; Cubo: cube-shaped; Scypho: cup-shaped; Hydros: sea serpent; Stauro: cross-shaped). The term “zoa,” of course, refers to animals.

Most of the time you are stung in our local waters it involves the classes Hydrozoa or Scyphozoa. The Hydrozoans are a complex group of organisms but most species go through two distinct stages during their life cycle. The hydroid stage takes the form of a polyp which is composed of a stalk and tentacles at the end. Polyps can be single but are often colonial, connected by tube-like structures. Most polyps are specialized for feeding but others are used to reproduce. Reproductive polyps lack tentacles but have many buds which form the medusa stage of the organism for reproduction purposes. Medusae of the hydroids are similar in design but typically smaller than the medusae of the true jellyfish. Some hydroids also have specialized defensive polyps with numerous stinging cells and one species even has a specialized polyp that develops into a large balloon-like float that the others attach to (the man o’ war). There is one specific type of hydroid in our area that closely resembles a piece of branching brown algae, such as Sargassum. The polyps are scattered along the branches and when brushed against they fire their nematocysts (stinging cells) producing a painful sting. The burning sensation can last for several minutes and you would have sworn the only thing around you was a harmless piece of drift algae.

The true jellyfish, of Class Scyphozoa, also go through a polyp and medusa stage. The polyps of this class are typically single and settle to the bottom as larvae and attach themselves. Over time the polyps mature and produce other polyps by budding, or bud medusae off their upper surface. These jellyfish medusae are microscopic at this stage and many take years to reach maturity, complete with a cup-shaped (scypho= cup shaped) bell and tentacles hanging beneath.

The subsequent lives of these translucent marine creatures is no less intriguing than the processes involved in their development. Check out this website from the Smithsonian for more great information. The next time you feel the burn of a host of nematocysts injecting you with their potent venom, I dare you to stop for just a second to be amazed by the fascinating creature that you have just met. If you can pull this off you are well on your way to becoming the quintessential nature nut! Click here for helpful information if you are stung.

by Rick O'Connor | May 15, 2015

Following a previous article on the number of ways you can help sea turtles, this week we will look at ways that local residents can help keep our waterways clean. Poor water quality is a concern all over the country, and so it is locally as well. When we have heavy rain all sorts of products wash off into streams, rivers, bays, and bayous. The amount and impact of these products vary but most environmental scientists will agree that one of biggest problems is excessive nutrients.

Marine science students monitoring nutrient levels in a local waterway. Photo: Ed Bauer

Nutrient runoff comes in many forms. Most think of fertilizers we use on our lawns but it also includes grass clippings, leaf litter, and animal waste. These organic products contain nitrogen and phosphorus which, in excess, can trigger algal blooms in the bay. These algal blooms could contain toxic forms of microscopic plants that cause red tide but more often they are nontoxic and cause the water to become turbid (murky) which can reduce sunlight reaching the bottom, stressing seagrasses. When these algal blooms eventually die they are consumed by bacteria which require oxygen to complete the process. This can cause the dissolved oxygen concentrations to drop low enough to trigger fish kills. This process is called eutrophication. In addition to this, animal waste from birds and mammals contain fecal coliform bacteria. These bacteria are used as indicators of animal waste levels and can be high enough to require health advisories to be issued.

So what we can do about this?

- We can start with landscaping with native plants to your area. Our barrier islands are xeric environments (desert-like). Most of our native plants can tolerate low levels of rain and high levels of salt spray. If used in your yard they will require less watering and fertilizing, which saves the homeowner money. It also reduces the amount of fertilizer that can reach the bay.

- If you choose to use nonnative plants you should have your soil tested to determine which fertilizer, and how much, should be applied. You can have your soil tested at your county Extension Office for a small fee. Knowing your soil composition will ensure that the correct fertilizer, and the correct amount, will be used. Again, this reduces the amount reaching the bay and saving the home owner money.

- Where ever water is discharged into the bay you can plant what is called a Living Shoreline. A Living Shoreline is a buffer of native marsh grasses that can consume the nutrients before they reach the bay and also reducing the amount of sediment that washes off as well, reducing the turbidity problem many of our seagrasses are facing.

These three practices will help reduce nutrient runoff. In addition to lowering the nutrient level in the bays it will also reduce the amount of freshwater that enters. Decrease salinity and increase turbidity may be the cause of the decline of several species once common here; such as scallops and horseshoe crabs. Florida Sea Grant is currently working with local volunteers to monitor terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and scallops in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties. We are also posting weekly water quality data on our website every weekend. You can find each week’s numbers at http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu. If you have any questions about soil testing, landscaping, living shorelines, or wildlife monitoring contact Rick O’Connor at roc1@ufl.edu. Help us improve water quality in our local waters.

by Rick O'Connor | May 10, 2015

It is May and this is the official beginning of the sea turtle nesting season. These ancient creatures have followed this nesting cycle for centuries traveling the open ocean, feeding and resting on reefs, then returning to shore in the spring and summer to breed and lay their eggs on beaches and barrier islands. What is neat is that Dr. Archie Carr discovered they return to the same beaches near where they were born. So those visiting our beaches are in a sense, “our” turtles. Another interesting fact about panhandle sea turtles is that a significant number of male turtles are produced here. Gender in most turtles is determined by the temperature of the egg during incubation in the sand; colder temperatures producing males. Since the panhandle has cooler temperatures than the lower peninsula of Florida, we produce the majority of the males for our populations. This is also why we have fewer nests than south Florida, since it is the females who return to shore.

Tracks left by a nesting Green Sea Turtle. Courtesy of Gulf Islands National Seashore.

However, in the last 50 years more and more people have moved to the beaches and barrier islands of the panhandle and the sea turtles have run into problems continuing their ancient cycle. Four of the five species of sea turtles in the Gulf of Mexico are currently listed as endangered; the loggerhead is listed as a threatened species. Though they have issues with natural predators much of their trouble is due to human activities. HERE ARE FIVE THINGS YOU CAN DO TO HELP SEA TURTLE NESTING THIS SEASON.

- Offshore, more and more turtles are being struck by boats. These are air breathing reptiles and need to surface. Unfortunately nesting season is also during the height of fishing and diving season. Many boaters must follow no wake zones to reach open waters and want to open up the throttle when they do. As with manatees in our rivers we ask that you keep a lookout for the surfacing heads as you are heading to and from your destination.

- Both offshore and inshore sea turtles are encountering more plastics in the marine environment. Turtles become entangled in discarded fishing line and actually consume many forms of plastic debris drifting in the water column. One loggerhead found on Dauphin Island had 11 pounds of plastic lodged in its esophagus, which obviously kept it from feeding properly. When you go boating please develop some method of storing plastics and fishing line until you reach shore. Once you return to the boat ramp please use the fishing line recycle bins to discard your fishing line. Fishing line placed in these are recycled into new fishing line. If there is not a fishing line recycle bin at your boat ramp contact your County Sea Grant Agent to see if one can be placed there. If you are enjoying the beach from shore please discard of all solid waste in trash or recycle cans before leaving.

- On the beach many residents and visitors spend the day playing in the sand and building sand castles. This time long activity is great fun but leaving large holes in the sand when you leave has not only entrapped turtles but have been problems for turtle watch and safety vehicles using the beach. Please fill in your holes before you leave for the day.

- Another issue on the beach are chairs and tents left over night. Many residents and visitors staying on the beach for a week or longer like to keep their chairs and tents set up for the duration. However this has caused barrier, and sometimes entrapment, issues for the turtles. We ask all to remove these from the beach at the end of the day.

- And finally, the lights. 40-50% of our turtle nests in Escambia County are disoriented by artificial lighting. Most panhandle counties do have beach lighting ordinances. We ask both residents and visitors to become familiar with their ordinances and abide by them. Exterior lighting should be low to the ground, long in wavelength (yellow or red), and shielded to direct the light down. Interior lighting can be blocked by closing the shades, moving the light source away from the window, or simply turning them off. All counties’ ordinances have some version of these basic ideas.

With a little help from us, our sea turtles can continue their ancient cycle. These animals are fascinating to see and for many, the highlight of their trip to the beach. If you have questions about sea turtle biology or the local lighting ordinances contact your Sea Grant Agent at the county extension office.

by Mark Mauldin | May 10, 2015

Cogongrass seedheads are easily spotted this time of year.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

We are well into spring and a wide variety of plants are showing off their colorful blooms. As lovely as most of the blooms are, some springtime colors are an unwelcome sight. Such is the case with the showy, white seedhead that is produced by Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica). The presence of Cogongrass – a highly aggressive, invasive, perennial – in Florida is not news; it has been in Florida since at least the 1930’s. However, the white seedhead that it produces in the spring makes it easier to locate and identify. When the seedhead is not present, the somewhat boring looking grass has the ability to blend in with its surroundings. This makes it harder for un-expecting landowners to identify the new/small infestations which are much easier to eliminate than are larger, well established infestations.

While cogongrass spreads primarily by rhizomes the seedheads can make new infestations easier to find.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

Controlling cogongrass is not easy but it is necessary. If left uncontrolled cogongrass will continue to aggressively spread, displacing other desirable vegetation. Generally speaking, control is a multi-year process. Because the specific recommendations for controlling cogongrass can vary somewhat by situation it is highly advisable that you contact a UF/IFAS Extension Agent in your county if you suspect that you have cogongrass on your property.

The following description of cogongrass from UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants should help you identify cogongrass, even if the seedheads are gone.

“Cogongrass is a perennial that varies greatly in appearance. The leaves appear light green, with older leaves becoming orange-brown in color. In areas with killing frosts, the leaves will turn light brown during winter months and present a substantial fire hazard. Cogongrass grows in loose to compact bunches, each ‘bunch’ containing several leaves arising from a central area along a rhizome. The leaves originate directly from ground level and range from one to four feet in length. Each leaf is 1/2 to 3/4 of an inch wide with a prominent, off-center, white mid-rib. The leaf margins are finely serrated; contributing to the undesirable forage qualities of this grass. Seed production predominately occurs in the spring, with long, fluffy-white seedheads. Mowing, burning or fertilization can also induce sporadic seedhead formation. Seeds are extremely small and attached to a plume of long hairs.”

This is the time of year when cogongrass is the easiest to identify. Take advantage of this opportunity to locate new infestations and work with your county agent to develop a control plan. Once a plan is in place, follow it to the end. Stopping after the first year will practically ensure that control will not be achieved.

A relatively new patch of cogongrass recently found in Washington County.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

More information on cogongrass can be found by following the links below

![Life Stages of the True Jellyfish: Photo: By Matthias Jacob Schleiden (1804-1881) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/files/2015/05/Schleiden-meduse-2-202x300.jpg)