This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

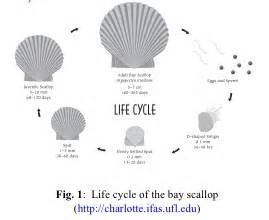

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025