This fish is a classic example of why scientists use scientific names. There are numerous common names for this species and multiple ones even in the Gulf region. Ling, Cabio, Lemonfish, Cubby Yew, Black kingfish, Black salmon, Crabeater, and Sergeant fish to name a few. The Cajun name for the fish is Limon – possibly where the name Lemonfish came from. Based on the references, Cobia seems to be the most accepted name, but Ling is often used here along the Florida panhandle. Again, this is a great example of why scientists use scientific names when writing or speaking about species. There is less chance for confusion. I say less because at times the scientific names change as well, and some confusion can still occur.

The scientific name for this fish is Rachycentron canadum. The genus name refers to the sharp spines of the first dorsal fin, which are sharp. The species name may refer to Canada. It is a common practice to give a species the name of the area/location in which it was first described. But it seems that Carlos Linnaeus, the biologist who first described it, used a specimen from the Carolinas to do so. So, not sure why the name was given4. It is the only North American fish in the family Rachycentridae and its closest relative are the remoras of the shark sucker family.

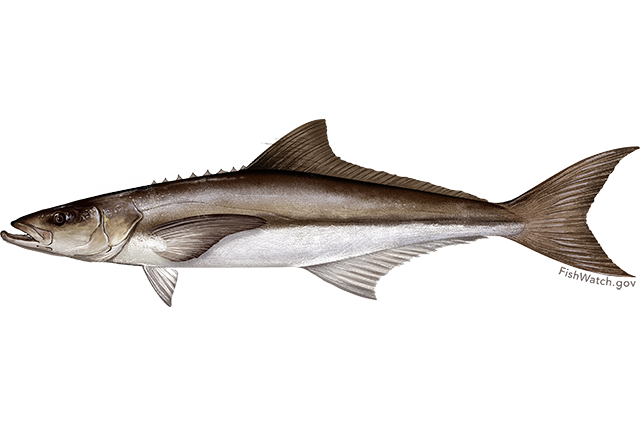

Some state that cobia have only one dorsal fin, but in fact they have two. The first is a series of 7-9 spines spaced with no membrane connecting. They are small, sharp, and somewhat embedded into the body. This is very similar to how the remoras and shark suckers first dorsal spines work, albeit remora’s first dorsal is softer. Cobia have a low depressed head that gives them the appearance of a shark when viewed from the side. It is often confused with sharks because they can get quite large – an average of five feet in length and up to 100 pounds in weight. The small juveniles resemble remora quite a bit. They are darker in color with pronounced lighter colored lateral stripes and their caudal fin (tail) is more lancelet and less lunate than the adults.

Biogeographically they are listed as worldwide, albeit tropical to subtropical – they do not like cold water. In the United States they are found all along the east and Gulf coast, but are absent from the west coast – again, a dislike for cold water. The literature states that there are two population stocks of cobia here. The Atlantic group and the Gulf of Mexico group all head south towards the Florida Keys for winter. However, breeding appears to take place in the northern parts of their range and so no genetics are exchanged while the two groups co-exist in the Keys. If this is the case, and it seems to be, there is a reproductive barrier, or behavioral barrier, that could, over time, isolate these two groups long enough that the gene pools could become different enough that attempts to breed between the groups would not produce viable offspring. If this were the case then they could be listed as subspecies, possibly the Atlantic and Gulf Cobia. But this has not happened. There are also studies that suggest in the Gulf there may be isolated groups. One comment is that there are cobia along Florida’s Gulf coast that migrate inshore and offshore but do not make the run to the Keys and back4. There are also studies that show a similar behavior with a group over near Texas. Obviously, there is a lot of work to be done on the movement and genetics of these possible subgroups to completely understand the biogeography of this animal. And don’t forget, there are cobia along the European/African coast of the Atlantic as well as the Indian and western Pacific.

But migrate they do. The “Ling Run”, as it known in the Pensacola area, is something many anglers wait for early in the year. We even have some local bait and tackle shops monitoring water temperature to announce when the run will begin. When water temperatures warm to 67°F it is time. Local anglers flock the Gulf side piers and head out on their boats with high ling towers to search for them. At the beginning of the ling run I have seen the inshore Gulf of Mexico littered with hundreds of boats covering the surface like small dots as far as you can see. One boat I remember was about 20 feet long and had precariously placed a large step ladder in the center as a “ling tower”. The angler was perched at the top of the ladder, holding on in the chop, searching the waters for his target.

Cobia will travel alone or in groups of up to 100 and are often attracted to objects in the water. Flotsam like Sargassum weed, or marine debris are places that anglers focus on. They are known to shadow sharks, manta rays, and sea turtles. I know anglers when they see a sea turtle begin throwing bait in that direction in hopes that a cobia is nearby. To the west of us in Alabama they seem to visit the offshore gas rigs and are attracted to the fishing piers many communities have extending into the Gulf – hence the large crowds of non-boating anglers visiting them during the run. Many anglers are known to drop FADs (Fish Attracting Devices) into the water to attract cobia, though these are not allowed during cobia/ling tournaments – which also pop up across the panhandle during the run.

Despite this apparent heavy fishing pressure, it is considered a sustainable fishery. Cobia mature at an early age, 2 years for males and 3 for females – and they live for about 12 years. They mass spawn in the northern waters. A typical season will find females breeding 15-20 times and producing 400,000 – 2,000,000 per spawn event. There is no evidence that this fishery is overfished, and there is commercial fishery for them as well. Due to their quick growth rates, large size, and high-quality flesh, there is interest in offshore aquaculture of this species.

It is an amazing fish. One of the best fish sandwiches I have ever had was a fresh ling sandwich. It is also a very interesting species from a biographical point. Enjoy the next “Ling Run” along the panhandle – or “cobia run”, or “lemonfish run”, which ever you wish to call it.

References

1 Bester, C. 2017. Discover Fishes; Rachycentron canadum. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/rachycentron-canadum/.

2 Lovestrand, E. 2021. Cobia: An Amazing Fish and Fishery for North Florida. University of Florida IFAS Blogs. https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2021/03/11/cobia-an-amazing-fish-and-fishery-for-north-florida/.

3 NOAA Fisheries. 2020. Cobia; Species Directory. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/cobia.

4 Staugler, B. 2016. Cobia Stripes. University of Florida IFAS Blogs. https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/charlotteco/2016/05/21/cobia-stripes/.

- Our Environment: Part 11 – We Need Water - July 7, 2025

- Our Environment: Part 10 – Improving Agriculture - June 20, 2025

- Marine Creatures of the Northern Gulf – Snails and Slugs - June 20, 2025