You might say this is a strange title – “meet the barnacle” – because everyone knows what a barnacle is… or do they?

As a marine science instructor, I gave my students what is called a lab practical. This is a test where you move around the room and answer questions about different creatures preserved in jars. Almost every time that got to the barnacle they were stumped. I mean they knew it was a barnacle but what kind of animal is it? What phylum is it in?

Going through a thought process they would more often than not choose that it was a mollusk. This makes perfect sense because of the calcium carbonate shell it produces. As a matter of fact, science thought it was a mollusk until 1830 when the larval stage was discovered, and they knew they were dealing with something different. It is not a mollusk. So… what IS it? Let’s meet the barnacle…

The barnacle is actually an arthropod. Yep… the same group as crabs and shrimp, insects and spiders. Weird right…

But that is because the creature down within that calcium carbonate shell is more like a tiny shrimp than an oyster. It is in the class Cirripedia within the subphylum Crustacea. It is the only animal in this class and the only sessile (non-motile) crustacean.

Barnacles are exclusively marine. This has been helpful when conducting surveys for terrapins or assessing locations for living shorelines – if you see barnacles growing on rocks, shells, or pilings, it is salty enough. There are over 900 species described and they live independently from each other attached to seawalls, rocks, pilings, boats, even turtle shells. Louis Agassiz described the barnacle as “nothing more than a little shrimplike creature, standing on its head in a limestone house kicking food into its mouth.”

The planktonic barnacle larva settles to the bottom and attaches to a hard substrate using a cement produced from a gland near the base of their first set of antenna (crustaceans, unlike insects and spiders, have two sets of antenna). It is usually head down/tail up and begins to secrete limestone plates forming the well known “shell” of the animal. Some barnacles produce a long stalk near the head end (called the peduncle) which holds the adhesive gland and it is the peduncle that attaches to the hard substrate, not the head directly. The goose neck barnacle is an example of this. We find them most often in the wrack along the Gulf side of our beaches attached to driftwood or marine debris.

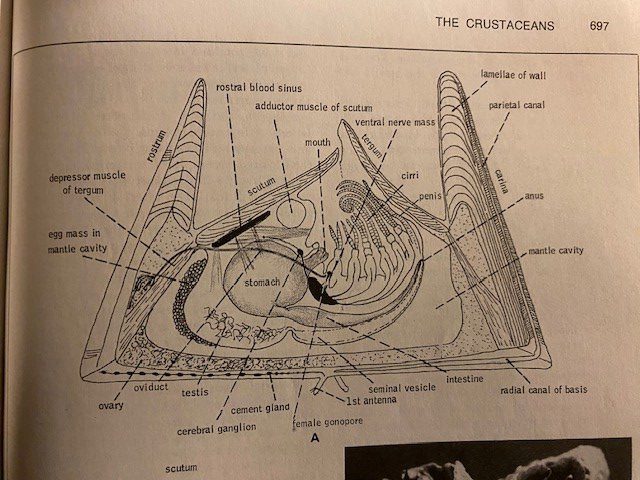

The “shell” of the barnacle is a series of calcium carbonate plates they secrete. These plates overlap and are connected by either a membrane or interlocking “teeth”. The body lies 90° from the point of attachment on its back.

There are six pairs of “legs” which are very long and are extended out of the “doors” of the shell and make a sweeping motion to collect planktonic food in the water column. They are most abundant in the intertidal areas were there are rocks, seawalls, or pilings.

Most species are hermaphroditic (possessing both sperm and egg) but cross fertilization is generally the rule. Barnacles signal whether they are acting males or females via pheromones and fertilization occurs internally, the gametes are not discharged into the water column as in some mollusks and corals. The developing eggs brood internally as well. Our local barnacle (Balanus) breeds in the fall and the larva (nauplius) are released into the water column in the spring by the tens of thousands. The larva goes through a series of metamorphic changes until it settles on a hard substrate and becomes the adult we know. They usually settle in dense groups in order to enhance internal fertilization for the next generation. Those who survive the early stages of life will live between two and six years.

So, there you go… this is what a barnacle is… a shrimplike crustacean who is attached to the bottom by its head, secretes a fortress of calcium carbonate plates around itself, and feeds on plankton with its long extending legs. A pretty cool creature.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025