The leatherback sea turtle is the largest of the five species that have been found in the northern Gulf of Mexico. With a carapace (top shell) length between 6-7 feet and weighing between 800-1000 pounds it is truly a magnificent creature. Any encounter with them is amazing.

Most encounters occur with fishermen or divers who are out searching for artificial reefs to fish or dive. Though very rare, they have been known to nest in this area. They feed exclusively on jellyfish and will follow them close to shore if need be. But what do leatherbacks do with most of their time? Do they hang offshore and follow jellyfish in? Do they circle the entire Gulf of Mexico and we see them as they pass? Based on past studies, many encounters with this turtle occur in the warmer months. They often become entangled in commercial fishing longlines set in the central Gulf of Mexico. But what do they do during the fall and winter? One of the tagging projects presented at a recent workshop tried to answer that question.

The project was led by Dr. Christopher Sasso of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. The tag chosen for this was a satellite tag. Since the leatherback must surface to breath air, and often is found near the surface following jellyfish, orbiting satellites would be able to follow them. As we mentioned in Part 1, catching the creature is step 1, and catching a six-foot 1000-pound sea turtle is no easy task.

The team used a spotter aircraft to locate the turtles. Once found, the pilot would radio the chase boat who would zip in with a large net. The net was connected to a large metal hoop and was designed to give way once it was around the turtle. Once in the net the turtle was hauled onto a small inflatable boat where the work of tagging could be done. They would measure the animal, take blood samples, place a PIT tag within them (similar to a microchip in your pet) and then attach the satellite tag by a tether to the tail end of the turtle before releasing it. The entire operation took less than 30 minutes.

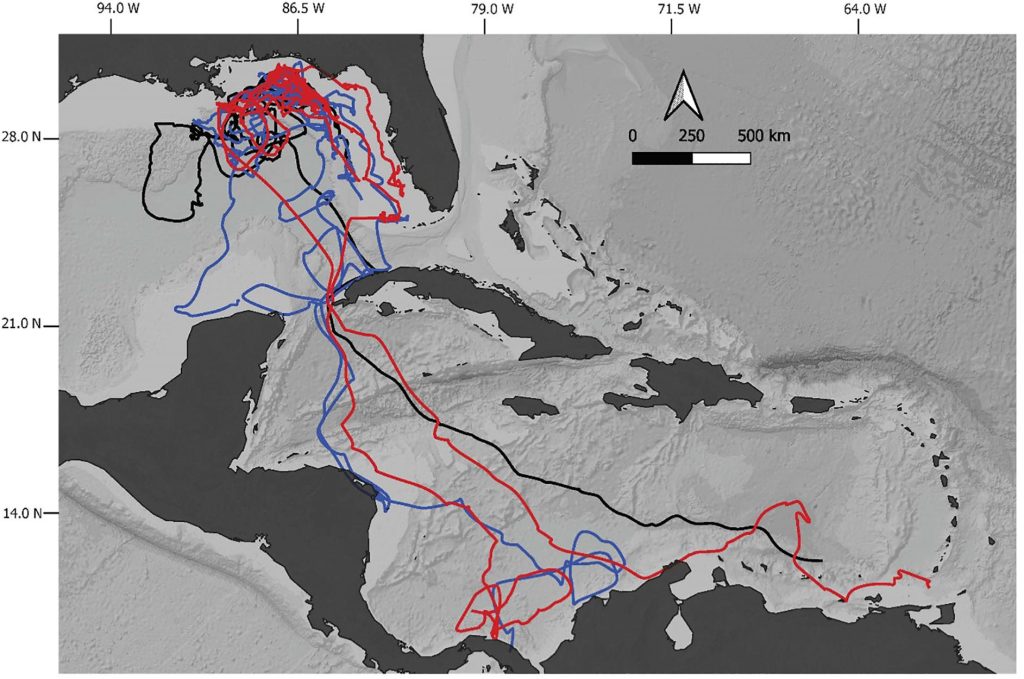

Between 2015-2019 19 leatherbacks were tagged in the northern Gulf. 17 of these were females and 2 were males. Data obtained from these tags ranged between 63 and 247 days at liberty. The behavior the team noticed was divided into foraging behavior (feeding on jellyfish) and transiting behavior (direct swimming ignoring all).

The turtles foraged in this part of the Gulf until the fall season. At that point most of them moved south along the Florida shelf, past the western peninsula of the state, heading towards the Keys. A few chose to swim directly south against the Loop Current, and a small number remained in the area.

Those moving along the Florida shelf appeared to be foraging as they went. Those crossing the open Gulf may have foraged some but seemed to be focused on getting south to the nesting beaches. Almost all of the turtles entered the Caribbean on the east side of the Yucatan channel, following the currents, with their final destination being their nesting beaches. When they returned, they did so in the warmer months and used the western side of the channel – again following the currents – until they once again reached the northern Gulf and foraging began again. One interesting note from this study, the two males tagged did not leave the Gulf.

The tagging studies do show that leatherbacks use the Gulf of Mexico year-round. They usually head south to the Caribbean when it gets colder and use the currents to do so. It is during the warmer months we are most likely to see them here foraging on jellyfish. It is an amazing experience to encounter one of these large turtles. I hope you get to experience it one day.

Reference

Sasso, C.R., Richards, P.M., Benson, S.R., Judge, M., Putman, N.F., Snodgrass, D., Stacy, B.A. 2021. Leatherback Sea Turtles in the Eastern Gulf of Mexico: Foraging and Migration Behavior During the Autumn and Winter. Frontiers in Marine Science., Vol. 8., https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.660798.

- Our Environment: Part 11 – We Need Water - July 7, 2025

- Our Environment: Part 10 – Improving Agriculture - June 20, 2025

- Marine Creatures of the Northern Gulf – Snails and Slugs - June 20, 2025