Recently I participated in a local festival to educate the public about the Rice’s Whale – the newly described species in the Gulf of Mexico that is now listed as critically endangered, possibly the most endangered whale in the world’s oceans. I honestly did not know enough about it to provide much education and chose to do terrapin conservation at my table instead (something I know more about) but have since learned much about this new member of the Gulf community.

One of the more frequent comments I heard during the event was “I did not know we even had whales in the Gulf”. This is understandable since we rarely see them – most of us have never seen one. When we think of whales we think of colder climates like Alaska, New England, and the colder waters off California. But many large whales must give birth to their smaller calves in warmer waters – so, they make the trek to tropical locations like Hawaii and Florida to do so. But there are also resident whales in the tropical seas.

You first must understand that the term “whale” does not only mean the large creatures of whale hunting fame, but any member of the mammalian order Cetacea. Cetaceans include both the large baleen whales – like the blue, gray, and right whales – but also the toothed whales – like the sperm, orca, and even the dolphins.

There are 28 cetaceans that have been reported from the Gulf, 21 of those routinely inhabit here. Most exist at and beyond the continental shelf – hence we do not see them. Only two frequent the waters over the shelf – the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin and the Atlantic Spotted Dolphin, and only one is routinely seen near shore – the Atlantic Bottlenose Dolphin.

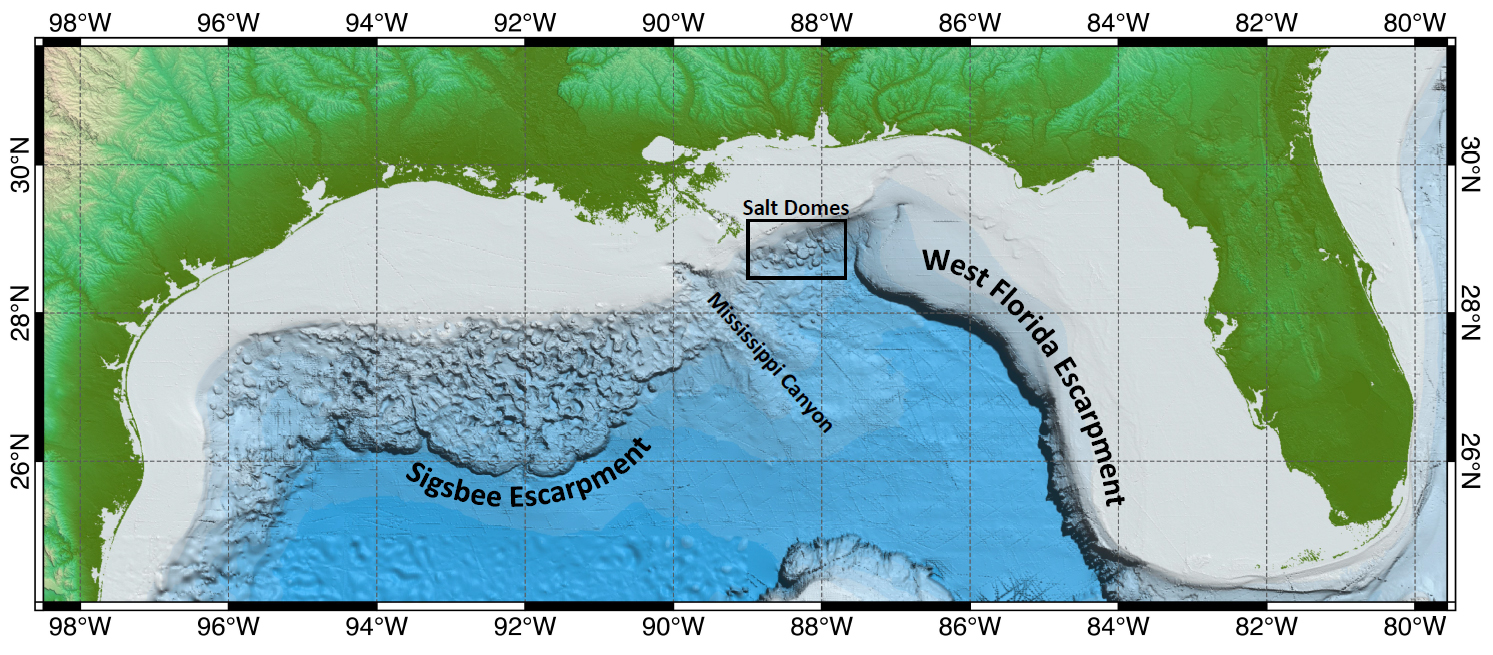

This image shows the location of the continental shelf and thus the location of most of the whales found in the Gulf of Mexico. Image: NOAA.

But offshore, out at the edge of the continental shelf, exists several species of large and small cetaceans. The endangered Sperm, Sei, Fin, Blue, Humpback, and Northern Right whales have been seen. Of those only sperm whales are common. Others include several beaked whales (which resemble dolphins but are much larger), large pods of other species of dolphins, pygmy and dwarf sperm whales, pygmy and false killer whales (as well as the killer whale itself), and other baleen whales such as the Minke and Bryde’s whale.

The Bryde’s whale is one of interest to this story.

The Bryde’s whale (pronounced “brood-duss” – Balaenoptera edeni) is a medium sized baleen whale, reaching lengths of about 50 feet and weighing 30 tons. It is often confused with the larger sei whale. They are found in tropical oceans across the planet and are not thought to make the large migrations of many whales due to the fact it is already here in the tropics for birth, and its food source is here as well. They reside in the northeastern Gulf of Mexico extending from the DeSoto Canyon, off the coast of Pensacola, to the shelf edge near Tampa. They appear to travel alone or in small groups of 2-5 animals. They feed on small schooling fish, such as pilchards, anchovies, sardines, and herring. Their reproductive cycle in the Gulf is not well understood.

The Bryde’s whale was thought to be the only resident baleen whale in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: NOAA.

Strandings have occurred – as of 2009, 33 have been logged. There are no records of mortality due to commercial fishing line entanglement, but vessel strikes have occurred. Due to their large population across the planet, they were not considered for listing under the Endangered Species Act, but that may change in the Gulf region due to human caused mortality. Between 2006-2010 it was estimated that 0.2 Bryde’s whales died annually due the vessel strikes.

In the 1960s Dr. Dale Rice described the Gulf of Mexico population as a possible subspecies. It is the only baleen whale that regularly inhabits the Gulf of Mexico. And ever since that time scientists examining stranded animals thought they may be dealing with a different species.

In the 1990s Dr. Keith Mullin began examining skull differentiation and genetic uniqueness from stranded animals of the Gulf population. Dr. Patricia Rosel and Lynsey Wilcox picked up the torch in 2008. In 2009 a stranded whale, that had died from a vessel strike, was found in Tampa Bay and provided Dr. Rosel more information. In 2019 a stranded whale, that had died from hard plastic in gut in the Everglades, was examined by Dr. Rosel and her team and, with data from this skull, along with past data, determined that it was in fact a different species. The new designation became official in 2019.

The new whale was named the Rice’s whale (Balaenoptera ricei) after Dr. Dale Rice who had first describe it as a subspecies in the 1960s. With this new designation everything changed for this whale. This new species only lives in the Gulf of Mexico, and it was believed there were only about 50 individuals left. Being a marine mammal, it was already protected by the Marine Mammal Protection Act, but with this small population it was listed as critically endangered and protected by the Endangered Species Act.

New reviews and publications began to come out about the biology and ecology of this new whale. Rice’s whales do exist alone or in small groups and currently move between the 100m and 400m depth line along the continental shelf from Pensacola to Tampa. Diet studies suggest that it may feed near the seafloor, unlike their Bryde’s whale cousins. They may have lived all across the Gulf of Mexico at the 100-400m line at one time. They prefer warmer waters and do not seem to conduct long migrations.

Being listed under the Endangered Species Act, NOAA National Marine Fisheries (NMFS) was required to develop a recovery plan for the whale. NMFS conducted a series of five virtual workshops between October 18 and November 18 in 2021. Workshop participants included marine scientists, experts, stakeholders, and the public. There were challenges identified from the beginning. Much of the natural history of this new whale was not well understood. Current and historic abundance, current and historic distribution, population structure and dynamics, calving intervals and seasonality, diet and prey species, foraging behavior, essential habitat features, factors effecting health, and human mortality rates all needed more research.

At the end of the workshop the needs and recommendations fell into several categories.

Management recommendations

- Create a protected area

- Restrict commercial and recreational fishing in such – require ropeless gear

- Require VMS system on all commercial and recreational vessels

- Require reporting of lost gear and removal of ghost gear

- Risk assessment for aquaculture, renewable energy, ship traffic, etc.

- Prohibit aquaculture in core area and suspected areas

- Reduce burning of fossil fuels

- Prohibit wind farms in core area

- Renewable energy mitigation – reduce sound, night travel, passive acoustic

- Develop spatial tool for energy development and whale habitat use

- Require aquaculture to monitor effluent release

- Develop rapid response focused on water quality issues

- Develop rapid response to stranding events

- Reduce/cease new oil/gas leases

- Reduce microplastics and stormwater waste discharge

- Work with industry to use technologies to reduce noise

- Reduce shipping and seismic sound within the core area

- Restrict speed of vessels

- Maintain 500m distance – require lookouts/observers while in core

- Consider “areas to be avoided”

Monitoring recommendations

- Long-term spatial monitoring

- Long-term prey monitoring

- Electronic monitoring of commercial fishing operations

- Necropsies for pollution and contaminants

Outreach and Engagement are needed

Top Threats to Rice’s Whale from the workshop Include:

- Small population size – vessel collisons

- Noise

- Environmental pollutants

- Prey – Climate change – marine debris

- Entanglement – disease – health

- Offshore renewable energy development

The Endangered Species Act (ESA) requires the designation of critical habitat for listed species. In July 2023 NOAA proposed the area along the U.S. continental shelf between 100-400 meters depth as critical habitat. Comments on this designation were accepted through October 6, 2023.

Vessel strikes are a top concern. It is understood that the most effective method of reducing them is to keep vessels and whales apart and reduce vessel speeds within the approved critical habitat.

On May 11, 2021, NOAA Fisheries received a petition submitted by five nongovernmental agencies and one public aquarium to establish a year-round 10-knot vessel speed limit in order the protect the Rice’s whale from vessel collisions. The petition included other vessel mitigation measures. On April 7, 2023, NOAA published a formal notice in the Federal Register initiating a 90-day comment period on this petition request. The comment period closed on July 6, 2023, and they received approximately 75,500 comments. After evaluating comments, and other information submitted, NOAA denied the petition on October 27, 2023.

NOAA concluded that fundamental conservation tasks, including finalizing the critical habitat designation, drafting a species recovery plan, and conducting a quantitative vessel risk assessment, are all needed before we consider vessel regulations. NOAA does support an education and outreach effort that would encourage voluntary protection measures before regulatory ones are developed.

On that note, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) did issue voluntary precautionary measures the industry could adopt to help protect the Rice’s whale. These include:

- Training observers to reduce vessel collisions.

- Documenting and recording all transits for a three-year period.

- All vessels engaged in oil and gas, regardless of size, maintain no more than 10 knots and avoid the core area after dusk and before dawn.

- Maintain 500m (1700 feet) distance from all Rice’s whales.

- Use automatic identification system on all vessels 65’ or larger engaged in oil and gas.

- These suggestions would not apply if the crew/vessel are at safety risk.

So…

This is where the story is at the moment…

This is what is up with the Rice’s whale in the Gulf of Mexico.

We will provide updates as we hear about them.

References

1 An Overview of Protected Species in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Fisheries Service, Southeast Regional Office, Protected Resources Division. 2012. https://www.boem.gov/sites/default/files/oil-and-gas-energy-program/GOMR/NMFS-Protected-Species-In-GOM-Feb2012.pdf.

2 Rosel, P.E., Mullin, K.D. Cetacean Species in the Gulf of Mexico. DWH NRDA Marine Mammal Technical Working Group Report. National Marine Fisheries Service. Southeast Fisheries Science Center.

https://www.fws.gov/doiddata/dwh-ar-documents/876/DWH-AR0106040.pdf.

3 A New Species of Baleen Whale in the Gulf of Mexico. 2024. NOAA Fisheries News.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/feature-story/new-species-baleen-whale-gulf-mexico.

4 Rice’s Whale. NOAA Fisheries Species Directory.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/rices-whale.

5 Rice’s Whale. Marine Mammal Commission.

https://www.mmc.gov/priority-topics/species-of-concern/rices-whale/.

6 Rice’s Whale: Conservation & Management. NOAA Species Directory. 2024.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/rices-whale/conservation-management.

7 BOEM Issues Voluntary Precautionary Measures for Rice’s Whale in the Gulf of Mexico. 2023. U.S. Department of Interior. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management.

8 NOAA Fisheries Denies Petition to Establish a Mandatory Speed Limit and Other Vessel Mitigation Measures to Protect Endangered Rice’s Whales in the Gulf of Mexico. NOAA Fisheries News. FB23-079. Gulf of Mexico Fishery Bulletin. October 27, 2023.

9 Petition to Establish Vessel Speed Measures to Protect Rice’s Whale. NOAA Fisheries. Protected Resources and Actions.

https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/action/petition-establish-vessel-speed-measures-protect-rices-whale.

10 Denial of Gulf Protections Could Lead to the “Permanent Loss” of Rice’s Whale. Jim Turner. WUSF News. October 31, 2023.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025