Many of us are given that Birds and the Bees talk; another majority have had to give it as an adult to their kids. It is usually an awkward talk, but someone had to step up to the plate and put on a straight face. I am happy to be the one today to discuss one section of the Birds and the Bees of the Sea, batch spawning. Batch spawning, also known as broadcast spawning, is the coordinated release of gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water column. Batch spawning is not just relegated to fish, many species of invertebrates also batch spawn. Some of the most commonly encountered batch spawners include Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus), Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Red Drum (Sciaenops ocellatus), Red Snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), and Gag Grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis), to name a few. In fact, most gamefish species in the Gulf of Mexico are batch spawners. This has its advantages, but also has its major disadvantages. We will dive headfirst into a few representative species of saltwater organisms that batch spawn, and their respective life stages to help shed some light on reproduction in the marine world.

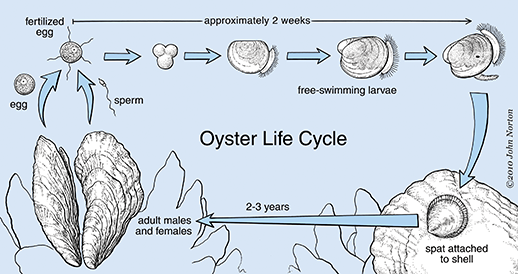

Eastern Oysters are a perfect representative for invertebrate batch spawning. I have gone over their life cycle in a previous article (Click Here), but I will just quickly go over their spawning habits and life history. Eastern Oysters typically spawn during the changing of the seasons, particularly from Spring to Summer and Summer to Fall. As humans, we see these changing temperatures and weather fronts as an opportunity for a new wardrobe, but these changes are triggers for oysters to spawn. Once one oyster releases their gametes into the water all of the mature oysters in the area will start releasing their gametes. Waiting to sense for other gametes in the water is a very smart tactic. This allows for a coordinated spawn between masses of oysters and (hopefully) increases the fertilization rate of the eggs. Since oysters cannot move, batch spawning is the most beneficial way for them to reproduce. Females can release anywhere from 2 to 70 million eggs in one spawning event, with only a dozen or so becoming adults. Since they are batch spawners, the larvae are left unprotected by the parents and suspended in the water column for the first few weeks, leaving them susceptible to predation by filter feeders and bad water quality. Once the larvae have reached the pediveliger stage, they will settle out and “walk” along the bottom of the estuary until they find a suitable place to call home, usually another oyster or hard substrate. After 1-3 years, the oyster will mature and begin batch spawning when conditions are ripe, and the cycle continues!

Fish in the Lutjanidae (snapper) family are the perfect representative for batch spawning with fish. Snappers of all species are known to congregate and have mass spawning events typically around a full moon. The mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis) of South Florida and the Florida Keys are very well known for their ability to form massive congregations of tens of thousands of fish along the reef starting in April. Once the spawning commences, the mutton snapper will form a small subgroup of up to 20 fish in the late afternoon. This subgroup will travel to depths of up to 100ft to perform their spawning event. During this event, the female will signal to the males that she is about to release her eggs. The males will then rub up against the side of the female snapper, helping her release eggs while simultaneously releasing their milt (sperm). When the milt is released, the sperm is activated by the seawater and begins to swim. Eventually, the eggs are fertilized and an embryo is formed.

18 – 24 hours later, the embryo is now a larval fish consisting of a yolk sac and lacking a mouth, eyes, and most organs. The yolk sac consists of amino acids and other nutrients that provide energy to the developing larvae. These larval fish have until their yolk sac runs out to develop the lacking vital organs, which usually takes between 24 – 48 hours. Only a very small percent of juvenile snapper make it to adulthood due to predation during their larval stage and predation as a juvenile. In fact, sharks and other large predators will prey on the snapper as they congregate and spawn, and filter feeders like manta rays are known to pass through an active spawning congregation to consume all the fertilized eggs and larval fish.

Well, I hope I didn’t scar anyone too badly. Batch spawning is fairly common in the marine biology world, and you can sometimes experience a spawning event without even knowing it. As for positives, this allows for many eggs to be fertilized at a time multiple times a season and for the larval fish and shellfish to be distributed through the estuary and reef via tides and waves. A major negative is the vulnerability of the juvenile and larval fish and shellfish, but the sheer number of eggs produced and fertilized helps outweigh the high potential for predation and unexplained loss of fertilized eggs and juveniles.

References:

Oyster Spawning: https://www.umces.edu/news/the-life-of-an-oyster-spawning

Mutton Snapper Species Spawning Profile: https://geo.gcoos.org/restore/species_profiles/Mutton%20Snapper/

Mutton Snapper Aquaculture Profile: https://srac.msstate.edu/pdfs/Fact%20Sheets/725%20Species%20Profile-%20Mutton%20Snapper.pdf

- Bring Some Wild Game To Your Holiday Dinner - December 15, 2025

- Aquaculture in the Southern United States: Part 5 – North and South Carolina - December 8, 2025

- Aquaculture in the Southern United States: Part 4-Louisiana & Mississippi - October 29, 2025