Roundworms differ from flatworms in that… well… they are round. You might recall from Part 1 of this series that flatworms were flat which helps with exchange of materials inside and out of the body. Flatworms were acoelomates – they lack an interior body cavity and thus lack internal organs. So, gas exchange (etc.) must occur through the skin. And a flat body increases the surface area in order to do this more efficiently.

But roundworms are round, which reduces this surface area and reduces the efficiency of material exchange through the skin. Though gas exchange through the skin does happen, it is not as efficient. So, there is the need for internal organs and that means there is a need for an internal body cavity to hold these organs. But with the roundworms there is only a partial cavity, not a complete one, and the term pseudocoelomate is used for them. Though the round body has adaptations to deal with gas exchange, it is a better shape for burrowing in the soil and sediment.

There are about 25,000 described species of roundworms, though some estimate there may be at least 500,000. They are placed in the Phylum Nematoda and are often called nematodes. Nematodes live within the interstitial spaces of soil, sediment, and benthic plant communities. They have been found in the polar regions, the tropics, the bottom of the sea, and in deserts – they are everywhere. They are usually in high numbers. One square meter of mud from a beach in Holland had over 4,000,000 nematodes. Scientists have estimated that an acre of farmland may have at least 1 billion of them. A decomposing apple on the ground in an orchard had about 90,000 nematodes. So, they are found everywhere and usually in great abundance. There are parasitic forms as well and they attack almost all groups of plants and animals. Food crops, livestock, and humans have made this group of nematodes a concern in our society.

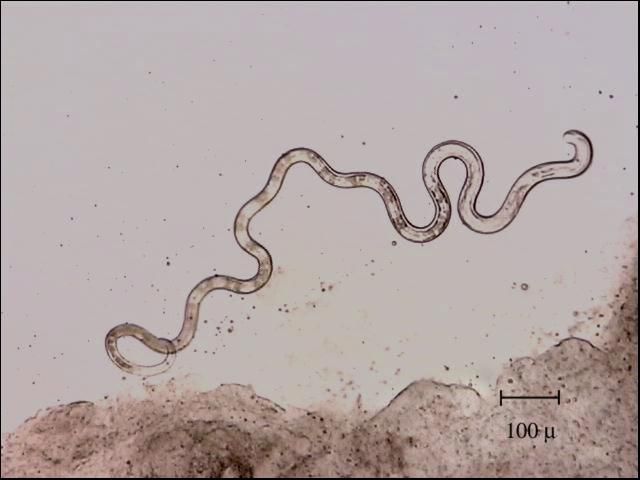

Like many pseudocoelomates, nematodes have an anterior end with a mouth, but no distinct head – rather two tapered ends. Most of the free-living nematodes are less than 3mm (0.1in), but some soil nematodes can reach lengths of 7mm (0.3in) and there are marine nematodes that can reach 5cm (2in.) – it is a group of small worms.

Roundworms usually need water in order to move, even the soil species. They typically wriggle and undulate, similar to a snake, when moving and under a microscope they wriggle quite fast. In aquatic habitats they may swim for a short distance, and a few terrestrial species can crawl through dry sand.

Many free-living nematodes are carnivorous and feed on tiny animals and other nematodes. Some feed on microscopic algae and fungi. Some terrestrial species pierce the roots of plants and digest the material within. Many marine species will feed on detritus lying on the seafloor. The carnivorous species may possess small teeth, and many have a stylet they can use to pierce prey or the plant root to access food. The mouth leads to a long digestive tract and eventually an anus – nematodes have a complete digestive tract.

The brain is basically a nerve ring near the head that leads to numerous nerve chords that run the length of the body. Sensory cells are most associated with the sense of touch and smell.

Having separate sexes is the rule for nematodes, but not for all. Males are usually much smaller and usually have a hooked posterior end which they use to hold the female during mating. 50-100 eggs are usually produced and laid within the environment.

Farmers and horticulturists are familiar with these free-living nematodes, but it is the parasitic ones that are most known to the general public. There are many different forms of parasitism within nematodes. Dr. L.H. Hyman categorized them as follows:

- Ectoparasites that feed on the external cells of plants – using their stylet to pierce the plant tissue and remove nutrients.

- Endoparasites of plants. Juveniles of some nematodes enter plants and feed on tissue. This can cause tissue death and gall-like structures.

- Some free-living nematodes, while juveniles, will enter the bodies of invertebrates and feed on the tissue when the invertebrate dies.

- Endoparasites within invertebrates as juveniles, but the adult stage is free-living.

- Some are plant parasites as juveniles and animal parasites as adults. The females live within the bodies of plant eating insects, where they give birth to their young. When the insects pierce the plant tissue, the juveniles enter the plant and begin feeding on it. When they mature into adults, they re-enter the insects and the cycle begins again.

- Those that live within animals. The eggs, or newly hatched young, may be free-living for a short period, where they find new animal hosts, but the majority of the life cycle occurs within the animal. Many known to us infect dogs, cats, pigs, cattle, horses, chickens, fish, and humans.

Heartworms, pinworms, and hook worms are names you may have heard. For dog nematodes, the eggs are released into the environment by the dog’s feces. Another dog eats this feces and becomes infected.

The nematode known as Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common parasitic worm in humans. It has been estimated that almost 1 billion people are infected with it. Female Ascaris release developing eggs into the environment via human feces. Other humans become infected after swallowing food or water containing the eggs. Once inside the human, the eggs hatch and penetrate the tissue moving into the heart and eventually the lungs. From here they crawl up the trachea inducing a coughing response which is followed by a swallowing response that moves the developing juvenile worm into the esophagus and eventually back to the intestines where the cycle begins again. Infections of this worm are more common where sanitation systems are not adequate and/or human feces are used as a fertilizer.

Hookworms are another human parasite that feed on blood and can cause serious infections in humans due to blood and tissue loss. Fertilized eggs of this worm are laid in the environment and re-enter new human host as developing juveniles by penetrating their skin. Once in the new host the developing worms are carried to the lungs via the circulatory system and work their way into the pharynx, are swallowed, and eventually end up in the intestine. Not all hookworm juveniles penetrate through the skin but rather enter the body when the person unknowingly consumes human feces. This can happen from not washing your hands or food (if human waste is used as fertilizer). Pinworms and whipworms are other nematodes that have similar life cycles. In Asia there are some nematodes that are passed to humans by biting insects.

The roundworm known as the nematode is a common issue for farmers, horticulturists, and as a parasite in some parts of the world. Their lifestyles, while being a potential problem for us, have been very successful for them. In the next edition in this series, we will learn more about the most advanced worms on our planet – the segmented worms. We will begin with the polychaetes.

References

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

Ascaris lumbricoides. 2024. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ascaris_lumbricoides.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025