Much of the phytoplankton found in the waters for the northern Gulf of Mexico are diatoms and dinoflagellates. We wrote about diatoms in our last article, here we will meet the dinoflagellates.

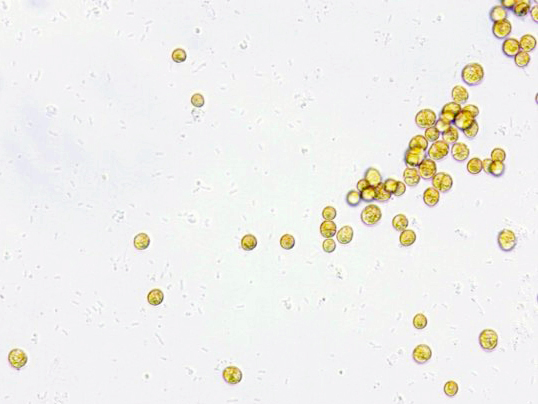

Like diatoms, dinoflagellates are microscopic phytoplankton drifting in the surface waters of the Gulf by the billions. We mentioned how abundant diatoms were, in the warmer seas, dinoflagellates are even more abundant. You collect them using a plankton net as you would diatoms. Observing them under the microscope they differ in a couple of ways. One, their shell is not made of clear silica but rather plates of cellulose with silica mixed in. Like diatoms, dinoflagellates possess several forms of chlorophyll but instead of fucoxanthins they possess carotenoids – giving them a brownish/red color. They also possess two hair-like tails called flagella – hence their name “dinoflagellate”. One flagella extends head to tail, the other encircles the dinoflagellate across their “girdle”. These flagella allow the cells to adjust and orient their position in the water column.

Dinoflagellates are microscopic plant-like plankton that possess two flagella.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

As with diatoms, dinoflagellates exist in the sunlit surface waters serving as “grasses of the sea”. They are an important part of the food chain and, along with their diatom cousins, produce about 50% of the world’s oxygen. But some members of this group are known for other roles they play.

Karenia brevis is the dinoflagellate primarily responsible for red tide in Florida. A plankton tow will find these organisms are always present – usually 1,000 cells/liter of water or less. Under certain conditions, these dinoflagellates begin to replicate in great numbers. Their numbers are large enough that the water will often change to a “reddish” color. In this case we are talking 1 million cells/liter or more. When disturbed, they will secrete a toxin – brevotoxin. This toxin can cause a variety of issues for marine life – and humans. Gastrointestinal, neurological, and respiratory problems in humans have all been associated with it. Red tides are famous for the large fish kills they generate and the mortality in marine mammals.

Being “plant-like” warm waters, sunlight, and nutrients will trigger a bloom. These blooms have been occurring for centuries and were logged by the Spanish explorers. Often, they generate offshore where the sunlit calm waters of the Florida shelf are bathed in nutrients from ocean currents coming from the seafloor. When wind conditions are right – these offshore blooms move inshore where they meet the nutrient rich discharge from rivers and estuaries – enhancing the blooms. Much of this discharge has higher levels of nutrients due to the actions of humans – such as fertilizers, animal and human waste.

Red tides are quite common off southwest Florida – happing frequently during the winter months. In the northern Gulf they are not as common. We do get blooms occurring here, though most are in the eastern panhandle, but sometimes the weather will drive blooms generated in southwest Florida up our way.

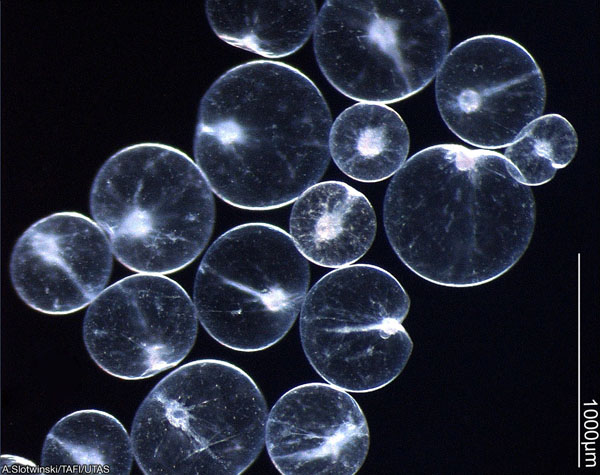

Noctiluca scitillans is another dinoflagellate that locals may know about – but did know they were dinoflagellates. What you may know it for is its ability to produce bioluminescence – “light in the sea” – what many locals called “phosphorus” when I was a kid. When disturbed a chemical reaction will create a blueish colored light. We see it during warm summer evenings when we walk through the water – or our footprints in the sand. From a boat you can see the blue light as fish swim by, or the wake from the moving boat. I remember once in high school we did a night dive near a pier where the bioluminescence from these dinoflagellates was so bright that you could see other divers, fish, and the pier without a dive light. Jim Lovell, commander of Apollo 13, tells the story of a night bombing mission he participated during the Korean War where his navigation lights went out on the return trip. The carrier was running without lights to avoid detection, but Lovell found the ship by the bioluminescent trail left by the propeller churning these dinoflagellates. This dinoflagellate is found all over the world.

Noctiluca are one of the dinoflagellates that produce bioluminescence.

Photo: University of New Hampshire.

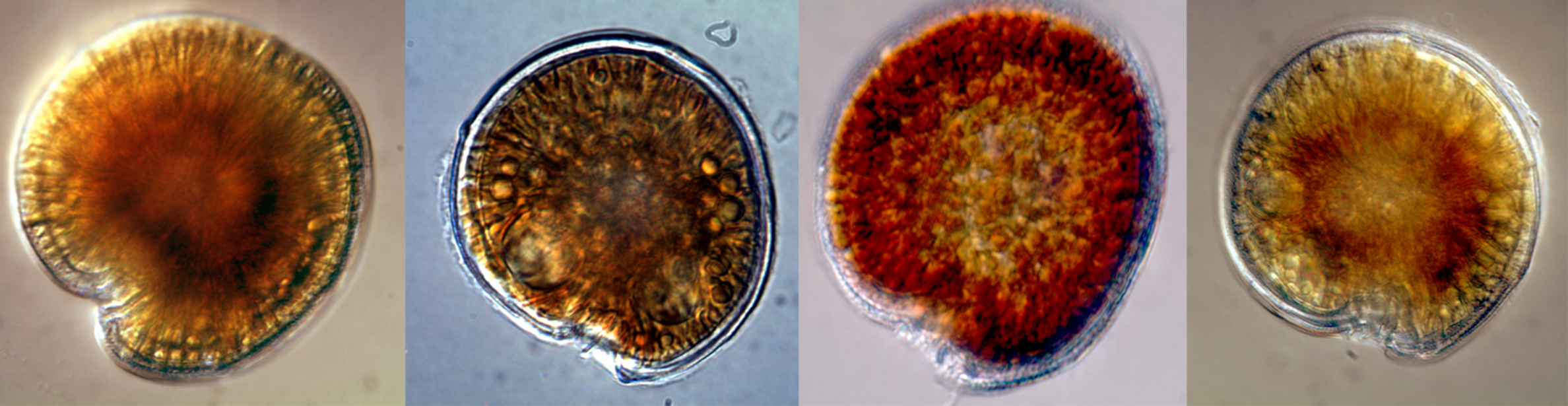

Zooxanthalle is a dinoflagellate you may not have heard of, but you may have heard of the coral bleaching that is occurring on reefs across the world. Corals are actually jellyfish and their tissue, like many jellyfish, is clear. The bright colors we are familiar with are caused by a symbiotic dinoflagellate that lives within the tissue of the corals. This symbiotic dinoflagellate is a group of several species known as zooxanthalle. In this partnership the photosynthetic zooxanthalle use waste products from the coral, and the sun, to photosynthesize. The products of photosynthesis are used to produce sugars, proteins, and other material that both the corals and the zooxanthalle need. Because of the need for sunlight, reefs usually occur in very clear – nutrient poor – waters. The bleaching we may be familiar with is caused when the reef is exposed to stress – high temperatures, pollutants, etc. and the zooxanthalle are expelled along with their photosynthetic pigments (the colors) – leaving only the clear tissue of the coral and a “white” appearance in color – bleaching.

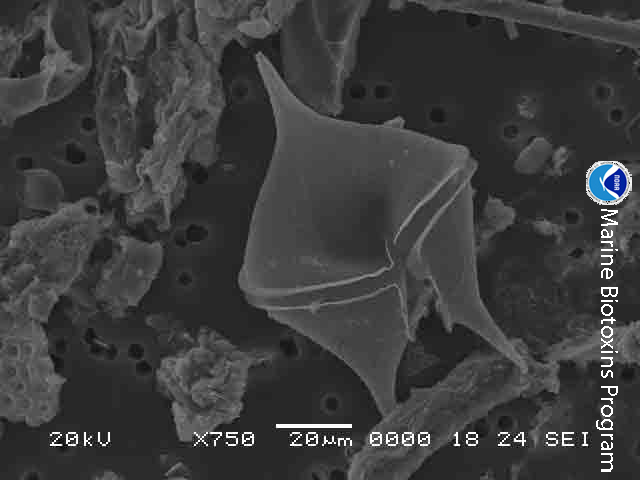

There are at least 18 species of dinoflagellates in the genus Gambierdiscus. These are not free-floating dinoflagellates, but ones they live on the bottom. You may not know them by name, but you may know them from the toxins they release when stressed – ciguatoxin. Ciguatoxins are a type of neurotoxin that can cause several illness – even death – in humans. The concentrations of ciguatoxin at the cellular level are minor and do not cause problems. However, as organisms graze on these dinoflagellates the toxins are not expelled from their bodies but are rather stored in the tissue. As you move up the food chain, no creature expels the toxins, and the concentrations increase in a process known as bioaccumulation. For humans the danger lies in eating the top predators in the food chain where the concentrations of ciguatoxin are high enough to cause problems – a condition known as ciguatera. Many who have visited the tropical parts of the world – where Gambierdiscus is most common – may have heard “you should not eat the barracuda” – or other large predators caught on a reef.

This situation has not historically been an issue for the northern Gulf of Mexico, but there are now records of this dinoflagellate north of the Florida Keys – as far north as North Carolina along the east coast. Scientists are watching the movement of this tropical group of dinoflagellates as the oceans warm.

The dinoflagellate known as Gambierdiscus. Known to cause ciguatera.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

There are thousands more species of dinoflagellates in the Gulf, and know they play many important roles in the ecology of our marine environment.

Resources

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

National Institute of Health (NIH).

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025