In the first article of this series, we discussed whether viruses were truly living organisms. Well, bacteria truly are. They possess all eight characteristics of life but differ from other forms of life in that they lack a true nucleus. Their genetic material just exists in the cytoplasm. This difference is large enough to place them in their own kingdom – Monera.

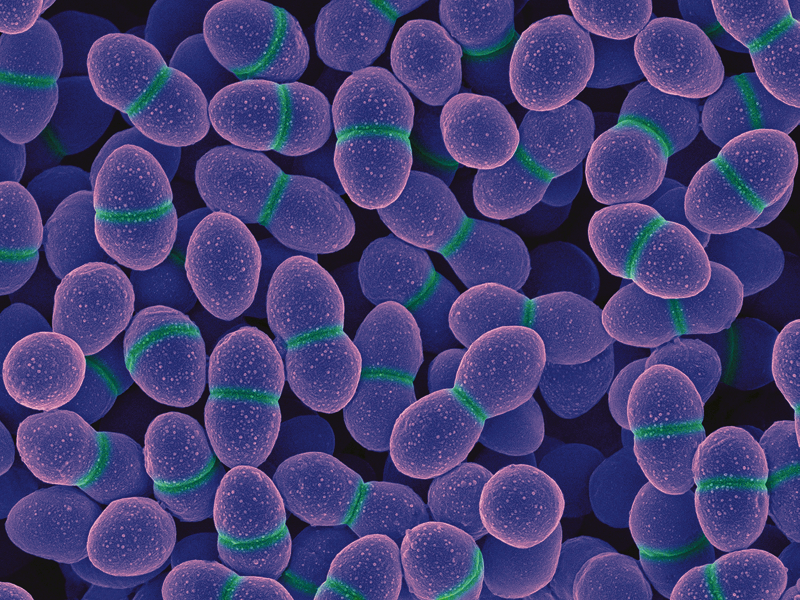

Bacteria are single celled creatures, though some “hook” together to form long chains. A single cell will average between 5-10 microns in size. This is much larger than a virus but smaller than many eukaryotic cells (those that possess a nucleus).

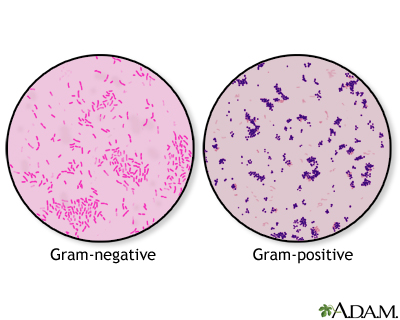

To further classify bacteria microbiologists will conduct a gram-stain test. Placing a cultured sample of bacteria on a slide, you “bath” them in what is called Gram-stain. Under the microscope the bacteria that appear “pink” are called gram negative, those that appear “purple” are gram positive. Thus, all bacteria can be quickly grouped into those that are gram negative and those that are gram positive.

After staining, gram negative bacteria appear pink in color; gram positive are purple.

Image: University of Florida

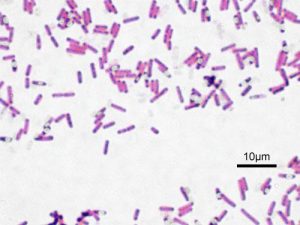

The next level of classification focuses on the shape of their cells. Those that are “rod-shaped” are called bacillus and often have the term in their name – such as Lactobacillus the bacteria found in milk that makes milk smell sour as their populations grow. The “sphere-shaped” bacteria are called coccus – such as Streptococcus (the bacterium that causes strep throat) and Enterococcus (the fecal bacterium used for monitoring water quality in marine waters). And the third group are “spiral-shaped” and are called spirillum – such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter both are human pathogens.

Bacteria are very abundant in the marine and estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They can be found floating in the water column, on the surface of the sediment, beneath the surface of the sediment, and on the bodies of marine organisms. When we think of bacteria we think of “dirty” conditions and disease, but many bacteria provide very important ecological benefits to the marine ecosystem and are “good” members of the community.

One important role some bacteria play is the conversion (“fixing”) of nutrients. Animals release toxic waste when they defecate and urinate. One of these is ammonia. Ammonia can bond with oxygen depleting the body of this needed element. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert toxic ammonia released into the environment into nitrite. Then another group of nitrogen fixing bacteria will convert nitrite into nitrate – a needed nutrient for plants, and eventually the entire food chain.

Some bacteria are excellent decomposers. When plants and animals die we say they “decay”. What is actually happening is the decomposing bacteria are converting nutrients in their bodies to forms that are usable by living organisms. One byproduct of this decomposition process is hydrogen sulfide – which smells like rotten eggs. In biologically productive ecosystems – like swamps and marshes – the smell of hydrogen sulfide is strong – often called “swamp gas”. It is the smell of nutrient conversion and much needed. Though in high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is toxic as well – there needs to be a balance. We see this same process happenings when we compost food waste to form fertilizers for our gardens.

One place where the smell of sulfur is very strong is near volcanic vents. If you have been to Yellowstone, or a volcano, the smell is very evident. There are what are termed “extreme bacteria” who can live in these very hot, almost toxic, environments. Just as plants take water and carbon dioxide and convert this to sugar in the process of photosynthesis, bacteria can convert toxic forms of sulfur into usable carbohydrates for other living organisms. In the 1970s marine scientists discovered thermal vents on the bottom of the ocean. These hot “chimneys” spew black clouds of smoke into the water column. Approaching these chimneys carefully they found water temperatures between 700-800°F! Living close to these chimneys they found communities of worms, shrimps, fish, and crabs. The walls of the chimneys are actually composed of sulfur fixing bacteria that are converting volcanic minerals and compounds into sugars in a process called chemosynthesis – which supports these deep-sea communities.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Of course, there are more familiar forms of bacteria that cause disease. Called pathogens – they can be problems for all marine life and sometimes humans. Fecal bacteria associated with human waste are not toxic in themselves at low concentrations. However, if their numbers increase (due to a sewage spill, etc.) these, and other possible pathogenic human bacteria, can be a human health issue. The Florida Department of Health monitors the fecal bacteria levels weekly at beaches where humans like to swim. High concentrations will require the department to issue health advisories. We know that all sorts of bacteria begin to replicate quickly in warmer conditions. This can be a problem with seafood that is not kept cold enough before serving. There are federal regulations on what temperatures commercially harvested seafood must be kept in order to be served or sold to the public. Federal and state agencies can monitor the temperatures of stored seafood as it moves from the fishing vessel to the table. But they cannot monitor it from your fishing rod to your table – that responsibility will fall on you. Pathogenic bacteria is the primary reason we refrigerate and/or freeze much of our food.

Though bacteria in general have a bad name, many species are not harmful to us and are a major player in the health of our estuarine and marine communities.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025