by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

Over the years I have received many calls from beach residents with concerns about coyotes. Encounters with this animal can be unnerving for many and the most common time of year for them is winter.

Coyote seen on Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Kristen Marks

A friend of mine who lives in the central part of Escambia County, told me he had seen several coyotes over Christmas break and several more along I-10 while driving back and forth from Mobile Alabama. Winter is breeding time for these animals. Early in the breeding season males are on the move seeking mates. Their searching may lead them to move at all times of the day and not just the dawn/dusk and evening times they typically do. Hence, more encounters.

Once pregnant, the females will find a den to give birth and care for the young. Dens are usually burrow areas, under logs, or within thick vegetation, but sometimes they have been found under decks or other debris in the yard. Gestation is about two months, and a litter is typically about six pups. Once born, the female will need to feed her young and will seek food from a lot of places and during all parts of the day. Hence, more encounters.

Coyotes are omnivores and have a wide diet. During the cold months their natural prey would be rodents and birds, but garbage and left out pet food are much easier to grab than birds and mammals, has a stronger smell, and higher caloric intake. It is more desired. Encounters with pet food can led to encounter with pets, and this could end bad for the pet. It is recommended that during these colder months you feed your pets, and store their food, indoors. Keeping your small pets indoors at night is recommended as well. Close and secure your garbage as best you can. Coyotes are pretty intelligent and will make an attempt to access this garbage if given the opportunity. Note that intentionally feeding a coyote is illegal. They have a natural fear of humans and if they are being fed, they will lose this fear which could lead to negative encounters with the animal.

A coyote is seen racing down Via DeLuna Blvd on Pensacola Beach

Photo: Shelley Johnson

Some may be concerned about the “pack behavior” of coyotes. Most are solitary but small packs of about six animals are known to move about the landscape usually calling to each other near dawn and dusk with their iconic howls and yips. The typical range for a group of six is about 10 square miles, which would lead to the argument that there are not many resident coyotes on Pensacola Beach or Perdido Key, but we know they are there. Some coyotes have been seen crossing the Bob Sikes Bridge between Pensacola Beach and Gulf Breeze near dawn, suggesting coyotes residing in Gulf Breeze may be using resources on Pensacola Beach.

If an encounter does happen, you should hold your ground. Coyotes do have a natural fear of humans and will typically flee. I recently encountered three animals napping near a large fallen tree while hiking in Colorado. I was not 100% sure what they were when I first saw what appeared to be ears sticking above the tree. Then a head popped up to look at me. I slowly approached, not recommended, and the coyotes immediately got up and ran. This is what you would expect them to do. Coyotes standing their ground and not leaving could suggest and animal who has found a reliable food source and may be willing to defend it. Contact the authorities if you believe this is the case.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

We do not know how many coyotes live in Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties, but it is fair to say they are common. Encounters are rare and the animal has learned to live near us without provoking problems. All the same, being aware of pets, pet food, and garbage this time of year is a good practice.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 6, 2022

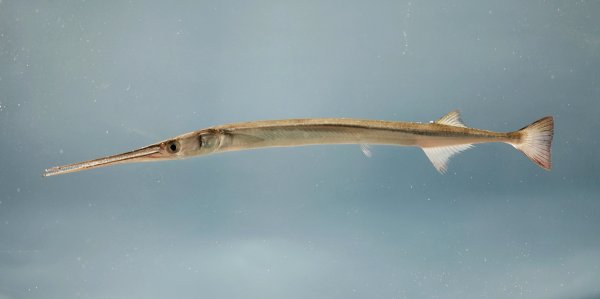

I remember first seeing a needlefish as a young boy on Pensacola Beach. We were either playing or snorkeling in Santa Rosa Sound and one of these long, sleek, “barracuda” looking fish swam by cruising the surface of the water. Your first reaction is danger. They have long jaws with very sharp teeth and move very “predator-like” through the water. Your fear is that if you get too close, they will turn and attack. I remember following them for several minutes watching how they looked at me but continued to search for prey. I was never attacked.

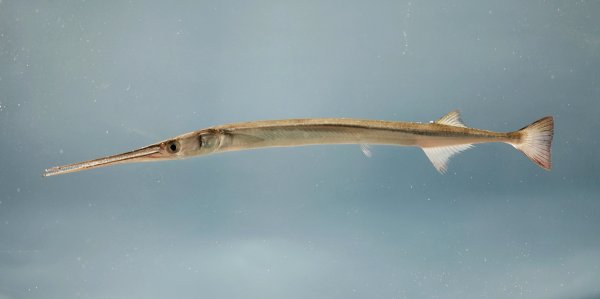

The Atlantic needlefish.

Photo: U.S. Geological Survey

Years later, as a marine science teacher, we were conducting a diversity and abundance study of nearshore fishes of the Pensacola Bay area. We would often catch these in our seine nets, and they would often get their numerous teeth snagged in the net. It took a careful maneuvering to remove them but in doing so, we could see their “nasty” side. They would try to bite, and bitten I was a few times. The needle like teeth did hurt a little and always drew blood. But once released they never turned on us, nor did the needlefish that were in the net and not snagged. We simply just released them.

I have often been asked by students “what do they eat?”. I have never read about, nor conducted a study, on their diet but would guess they prey on small fishes. Needlefish themselves are not terribly large, two feet being reported as the average length, so their prey could not be very large. Their long skinny snout and relatively small mouth with the lack of molars would suggest they must grab and swallow, almost whole, whatever lunch would be for that day. Fish that are only a few inches long at most. I have heard silversides, and killifish are popular targets for them, I can see this. I have seen them hunt in small groups, but mainly I see them alone. They themselves would be prey for larger predatory fishes in the bay area and birds, such as osprey, would hunt them due to their habitat of hunting at, or near, the surface.

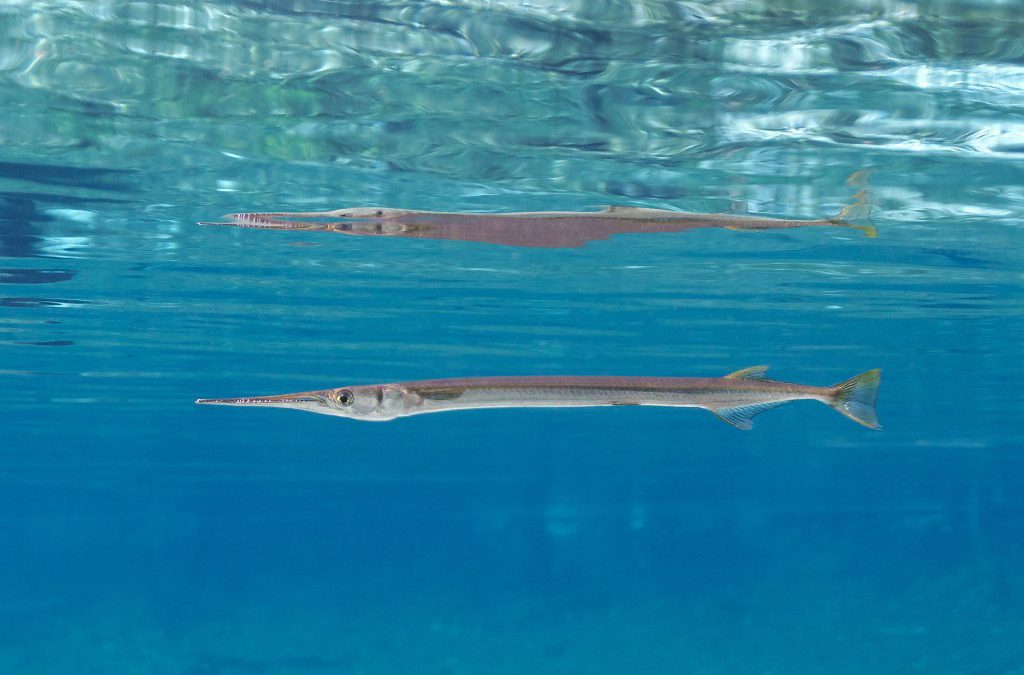

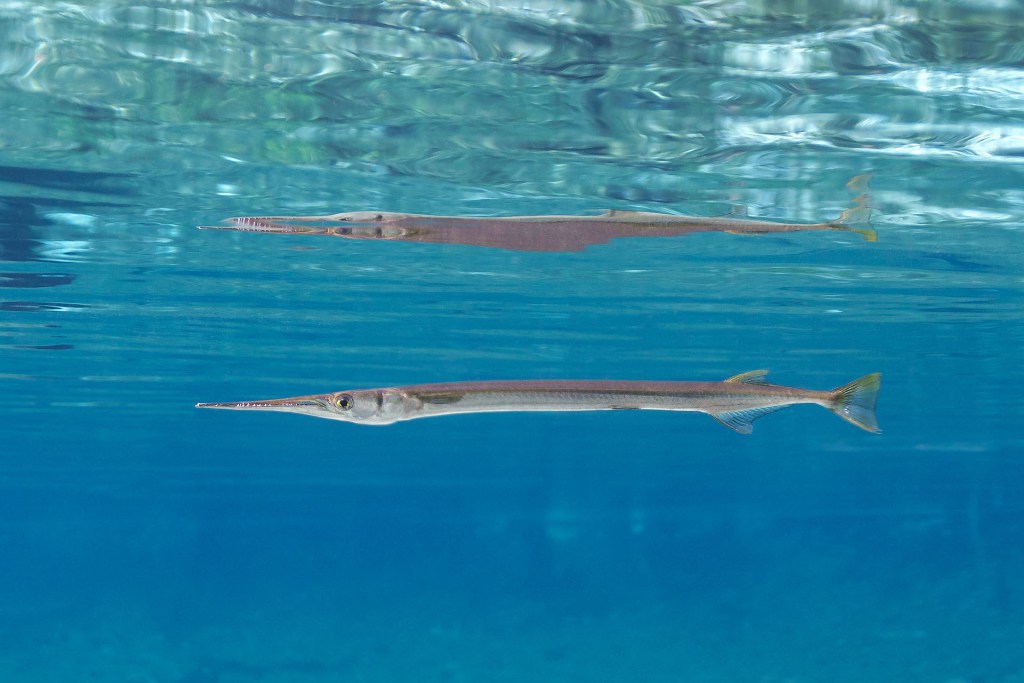

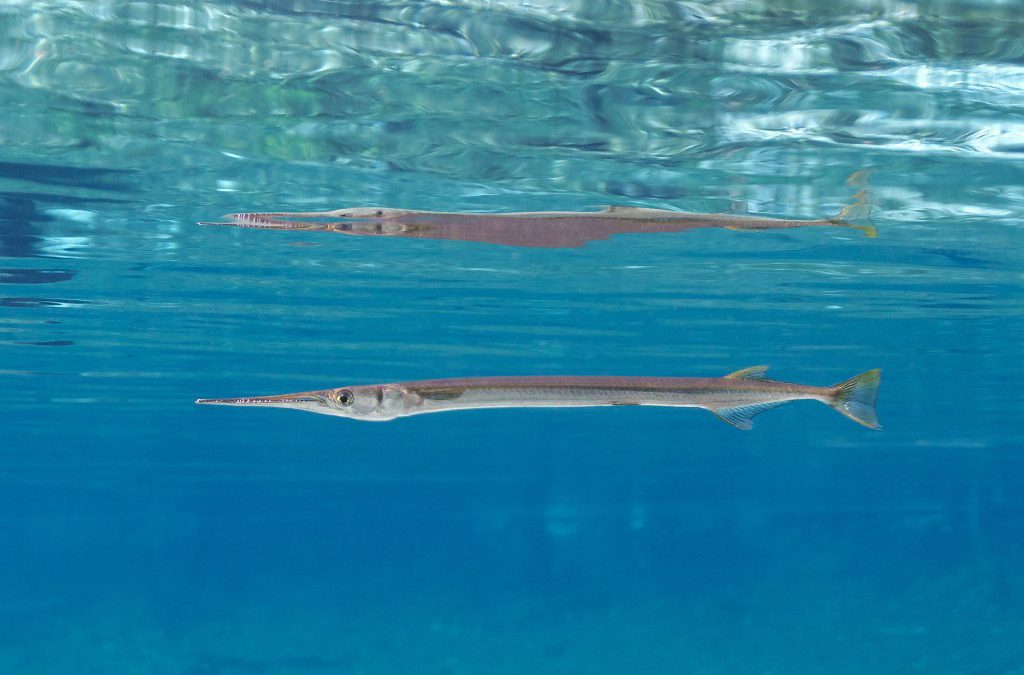

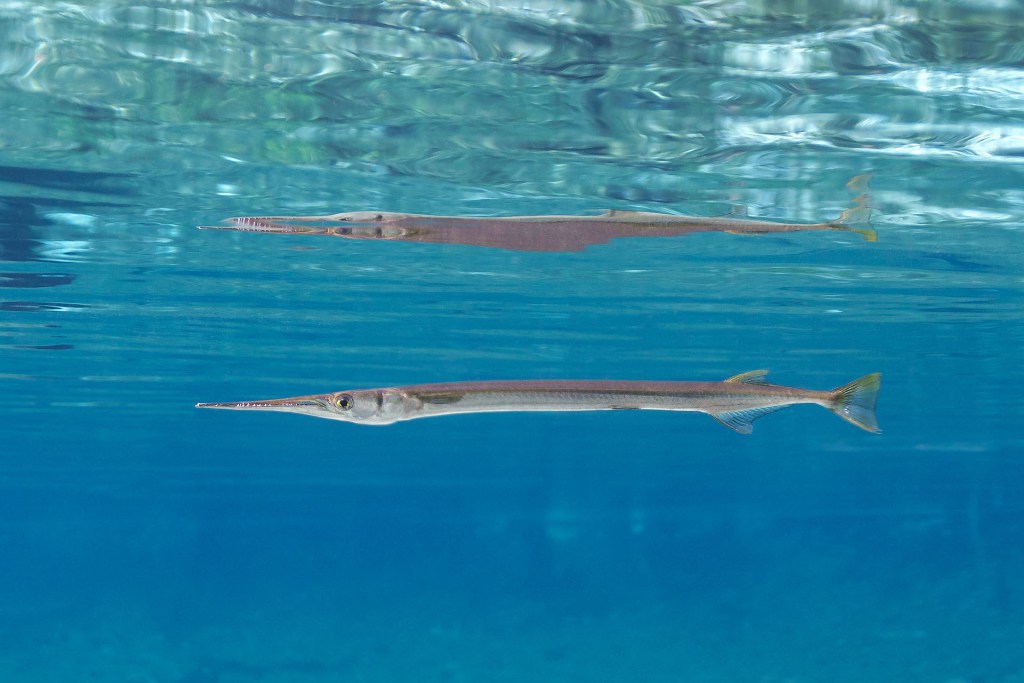

Swimming near the surface is a common place to find needlefish.

Photo: Florida Springs Institute

Though Hoese and Moore1 report four species in our area, it is the Atlantic Needlefish (Strongylura marina) that I caught most often. Honestly, it is very hard to tell the species apart just by looking at them. One, the Keeltail Needlefish (Platybelone argalus) lacks gill rakers, if you know what those are, and this cannot be determined unless you catch the fish and take a peek. That said, I did capture these while conducting that fish diversity study with my marine science class. Like the Atlantic Needlefish, the Flat Needlefish (Ablennes hians) and the Houndfish (Tylosurus crocodilus) – you have to love that name “crocodilus” – have gill rakers and are differentiated by the number of rays on their anal fins. Another feature not easily noticed while snorkeling with them. I have heard the Houndfish can be aggressive. Hoese and Moore report they are more common offshore. We did capture one in Pensacola Bay and did not notice a “nastier” attitude.

All four species have a wide geographic range; found along the Atlantic coast, throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, south to Brazil.

They are a common and interesting fish to see, and not dangerous as they may appear.

Reference

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station, TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 22, 2021

2021 Panhandle Terrapin Project Survey Report

Rick O’Connor, Florida Sea Grant, University of Florida / IFAS Extension, Escambia County

SITUATION

The diamondback terrapin (Malaclemys terrapin) is the only resident brackish water turtle in the United States. Ranging from Cape Cod Massachusetts to Brownsville Texas, this turtle is most often found in the salt marsh and mangrove habitats within this range.

The light colored skin and dark markings are pretty unique to the terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Terrapins are medium sized members of the Emydidae family, which includes the cooters, sliders, and box turtles. The carapace length of the larger females is about 10 inches, and she will weigh on average about 20 ounces. Males are smaller, 5-6 inches carapace and about 10 ounces. They are beautifully marked turtles having lighter skin with darker spots or bars. The carapace can have beautiful markings of spots and swirls, many times a brilliant orange in color. Because of this they are popular in the pet trade and illegal pouching is a problem across their range.

There are seven subspecies within this range.

- The northern terrapin ( t. terrapin) can be found from Massachusetts to the Chesapeake Bay area.

- The Carolina terrapin ( t. centrata) is found from the Chesapeake Bay area to the Daytona Beach area of Florida.

- The Florida east coast terrapin ( t. tequesta) is found from the Daytona Beach area to Miami-Dade County.

- The mangrove terrapin ( t. rhizophorarum) is found in the Florida Keys and along the Gulf coast to the Ten Thousand Islands area.

- The ornate terrapin ( t. macrospilota) can be found from the Ten Thousand Island area to Choctawhatchee Bay in the Florida panhandle.

- The Mississippi terrapin ( t. pileata) is found from Choctawhatchee Bay to the Louisiana/Texas state line.

- The Texas terrapin ( t. littoralis) is found along the coast of Texas.

The animal is quite well known in the Chesapeake Bay area where it was harvested in the 19th century as a food source. The popularity of “turtle soup” increased when President Lincoln included it as a local course for state dinners at the White House. The popularity increased the harvest to a point where terrapin farms began to supply the demand, many of these farms were in the south. Eventually the price became too high, and the popularity of the dish waned. At that point research into the animal began in earnest to assess how the commercial harvest had impacted the population. Much of this work was conducted in the early part of the 20th century. By the mid-20th century, a wired crab pot was developed for the harvest of blue crab, a popular fishery in the Chesapeake. Terrapins have a habitat of entering these crab pots and drowning. So, a new threat had emerged. About the same time the automobile was becoming more popular, bridges were being built to connect to barrier islands, and other locations, humans had not visited much before. This activity increased the number of nest predators for terrapins, raccoons being one of the larger problems.

Terrapins in a derelict crab trap (photo: Molly O’Connor)

All of these issues led to more research on terrapin biology and ecology. However, there was one region within their range that very little was known – the Florida panhandle. There were no scientific studies conducted in this part of their range and even their existence there was questioned.

REPSONSE

In response to the question of existence in the Florida panhandle, the Florida Turtle Conservation Trust and the Florida Diamondback Terrapin Working Group, reached out to the Institute of Coastal and Marine Studies (a high school marine science program in Escambia County, Florida). The objective was to have them conduct surveys in suitable terrapin habitat indicating presence/absence of terrapins between Escambia and Franklin Counties. Those surveys began in 2005 and by 2010 had been conducted in all six counties with at least one verified record in each of the six counties (Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, and Gulf). Terrapins did exist there.

Beginning in 2008 the team began to assess population status. Funding for mark/recapture was not available but a method of assessing relative abundance was being used in Mississippi and was chosen for the Florida panhandle. The method had made several assumptions –

- Each mature female nests every nesting season

- Each nesting female will lay more than one clutch each season but would not lay more than one within a 16-day period.

- The team had identified all terrapin nesting beaches in the region.

Based on this method, surveys were broken into 16-day intervals beginning April 1 and ending on July 1 (peak nesting period). Each track, or depredated nest, was counted and all sign of the track or nest removed so that it would not be recounted within that 16-day period. Each track would then represent a different female and over time the number of nesting females could be determined. Going on the argument that the sex ratio was 1:1 a relative abundance of adult terrapins could be determined. A study conducted in the Big Bend area of Florida by Suarez (Suarez, 2015) suggested the sex ratio was 1:3 in favor of males. A more recent study from the eastern panhandle conducted by Catizone (unpublished) suggests a 1:5 ratio in favor of males. Based on this we could develop a range of relative abundance from 1:1 to 1:5.

Note the track on this beach.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Egg shells indicate a depredated nest.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another metric used to measure relative abundance was a 30-minute head count. The team would sit in kayaks within the ponds where adults resided and count the number of heads in that time period. Again, this does not indicate a population but a relative abundance within that location.

Finally, in 2008 the team began to deploy modified crab traps to capture terrapins for a potential mark/recapture study, marking using a scute notching method. The traps were modified so that a captured terrapin would be able to surface and breath. These traps were set in potential adult residing locations for a five-day period beginning on a Monday and ending on a Friday.

A terrapin swimming near but not entering a modified crab trap.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The focus of the relative abundance and trapping portions of the project were Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties due to the fact the team resided there.

In 2012, the author left the marine academy and joined Florida Sea Grant. This project was not a high priority in the job description and effort on this waned until no surveys were conducted in 2014. However, in 2015 the author established a citizen science program to continue these surveys and they have done so since. The focus of those surveys has been frequency of occurrence (FOO – the number of surveys where either terrapins, or terrapin sign have occurred) and continuing the relative abundance data collection.

Citizen scientists have been crucial for the success of this project.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

In 2018 the U.S. Geological Survey joined the team. One member of USGS began coordinating citizen science work in the eastern panhandle (Bay, Gulf, and Franklin Counties as well as conducting research in the Gulf County area), and the author began coordinating citizen science work in the western panhandle (Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, and Walton Counties). With USGS help some tagging has begun with both PIT and satellite tags.

RESULTS

The 2021 results are from the western panhandle portion of the project.

In the western panhandle during 2021, 263 surveys were conducted by 41 trained volunteers who logged 1832 hours. These surveys occurred in Escambia, Santa Rosa, and Okaloosa Counties. Surveys were conducted at known nesting areas with some occurring at potential new nesting sites. The number of surveys where either terrapins, or terrapin sign, were encountered was 52. This is a frequency of occurrence (FOO) of 20% of the surveys an encounter occurred. The breakdown by county is below.

2021 Data from the Western Panhandle

| County |

# of sites surveyed |

# of surveys |

FOO |

# of heads seen |

Nesting detected |

Relative abundance |

| Escambia |

8 |

86 |

.02 |

1 |

Yes |

8-24 terrapins |

| Santa Rosa |

2 |

79 |

.11 |

0 |

Yes |

4-12 terrapins

2-6 terrapins |

| Okaloosa |

5 |

98 |

.42 |

357 |

Yes |

20-70 terrapins

4-10 terrapins |

| TOTAL |

15 |

263 |

.20 |

358 |

|

|

Three of the eight sites surveyed in Escambia County were known nesting beaches, but evidence of nesting was only found at one. The other five locations were potential nesting sites, but no evidence of nesting was found. Based on these surveys, nesting activity declined in 2021.

Both sites surveyed in Santa Rosa County were known nesting beaches and nesting was detected at both. One site has long term data that, based on this year’s surveys, suggest a decline in relative abundance.

One of the five sites in Okaloosa was a known nesting site. However, evidence of nesting at a additional site was found. An encounter of some kind was logged at four of the five sites surveyed. All of these are relatively new survey sites to the project and relative abundance data is minimal. However, based on these data, the relative abundance is quite high.

Data from 2007 – 2021 for all sites

| County |

# of sites surveyed |

# of surveys |

FOO |

# of nesting beaches found |

| Escambia |

22 |

291 |

.11 |

4 |

| Santa Rosa |

13 |

441 |

.32 |

2 |

| Okaloosa |

12 |

123 |

.36 |

2 |

| Walton |

3 |

4 |

.25 |

0 |

| TOTAL |

50 |

859 |

.25 |

8 |

Since the beginning of the project 859 surveys have been conducted in the four counties of the western panhandle and terrapins have been encountered 25% of the time. Of the 50 sites surveyed, 8 (16%) of those have found nesting activity.

Objective 1 has been completed. There are terrapins in the Florida panhandle.

Objective 2 – the relative abundance – is still not completely understood. There was a significant decrease in encounters when the citizen science project began in 2015.

The citizen science effort the FOO was much higher and increased annually. The citizen science effort began in 2015 and the FOO was much lower but increased annually as well. It is believed that the cause of this decline is ability for volunteers to find terrapins, terrapin heads, or evidence of nesting. It is believed the volunteers are getting better and that the data will eventually provide better information on terrapin abundance.

DISCUSSION

Objective 1 has been answered. There are terrapins in the Florida panhandle.

Objective 2 is still not understood. It is believed the higher FOO between 2007 and 2011 was probably due to the ability of the volunteers to detect terrapin or terrapin sign. So, it is not known at this time whether the relative abundance of these animals have declined in the western panhandle or not. As the volunteers get better, we will see over time how the numbers change.

The effort of mark/recapture using modified crab traps has not been very effective. Traps have been deployed with much effort at four sites with very little success. That portion of the project has been suspended while searching for a better method of capture.

At two of the long-term monitoring sites, the relative abundance data suggests a decline in terrapins at those locations. However, as mentioned, confidence in the relative abundance data needs to increase before any strong conclusions can be drawn. These data do suggest small populations at all locations, between 20-50 animals. The citizen science effort will continue, and we hope a more robust population study will follow.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The author would like to thank the students from the Institute of Coastal and Marine Studies at B.T. Washington High School for assistance developing and conducting the early portion of this project.

Tom Mann from the Mississippi Department of Wildlife for the protocol on relative abundance based on nesting activity.

George Heinrich (Florida Turtle Conservation Trust, Florida Diamondback Terrapin Working Group)

Dr. Joe Butler (University of North Florida, Florida Diamondback Terrapin Working Group)

Dr. Andy Coleman (Birmingham Audubon Society, Gulf Coast Diamondback Terrapin Working Group)

Dr. Thane Wibbels (University of Alabama Birmingham, Gulf Coast Diamondback Terrapin Working Group)

Dr. Ken Marion (University of Alabama Birmingham, Gulf Coast Diamondback Terrapin Working Group) for their assistance, guidance and advice on this project.

Dan Catizone (U.S. Geological Survey, University of Florida)

Dr. Margaret Lamont (U.S. Geological Survey)

for their assistance, guidance, advice, and supply support.

Bob Pitts (Gulf Islands National Seashore)

Bob Blais (Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center)

Jeanna Kilpatrick (Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance)

for taking the lead as county volunteer coordinators as well as surveyors.

And the 40 plus volunteers who have logged thousands of hours surveying sites in the western panhandle. We could not have done this without you.

Submitted:

December 22, 2021.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

Recently I watched a documentary on TV entitled The Loneliest Whale; the search for 52. The title grabbed my attention and so, I checked it out.

There are many forms of wildlife that are very hard to find in our area. But we continue to look.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Seems a decade or so ago the U.S. Navy was doing SONAR work in the Pacific between Washington and Alaska and detected a strange sound coming in at 52 hertz. They had not herd this before and would continue to hear it in different locations around the northern Pacific. Their first concern was it was something new from the Russians, but when they showed the graphs and played the recording to a marine mammologist named Dr. Watkins, they found that it was most likely a “biological” – mostly likely a whale.

The problem was that Dr. Watkins had never heard whales calling at 52 hertz. If it was a whale, it was calling a lot – but no other whales were answering. Hence the name “the loneliest whale”. If it was a whale, and no others would talk to it, it was kind of sad. But who was this whale? What kind was it?

Word of the loneliest whale spread around the world and many humans made a connection to this animal, possibly because of their own disconnect with their own species. Stories and ballads were written, and people began to feel for the poor animal that apparently had no friends.

This story caught the attention of a documentary film maker who was interested in finding “52”, as the whale became known. He solicited the help of other marine mammologists; Dr. Watkins had died. According to those marine mammologists, this was going to be VERY difficult. It is hard enough to find just a pod of whales in the open Pacific, much less a specific pod with a specific individual. But they were excited about the challenge of finding this one animal, “52”, and off they went.

As I was watching this documentary it reminded me of my own search here near Pensacola. In 2005, I was asked by members of state turtle groups if I could search to see if diamondback terrapins lived in the western panhandle. This turtle’s range is from Cape Cod Massachusetts to Brownsville Texas, but there were no records from the Florida panhandle. Did the animal exist there? I was running the marine science program at Washington High School at the time and thought this would be a good project for us. So, we began.

Mississippi Diamondback Terrapin (photo: Molly O’Connor)

This small turtle can be held safely by grabbing it near the bridge area on each side.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The students researched terrapin biology and ecology to determine the locations with the highest probability of finding, and we searched. I quickly found that the best time to search for terrapins was during nesting in May and June, and that the worst time to do a project with high school seniors was May and June. So, the project fell on my wife and me. For two years we searched all the “good spots” and found nothing. We placed “Wanted Poster’s” at boat ramps near the good spots with only calls about other species of turtles, not the terrapin.

Then one day in a call came in from a construction worker. Said he had seen the turtle we were looking for. For over a year we had been chasing “false calls” of terrapins. So, I was not overly excited thinking this would be another box turtle or slider. I asked a few questions about what he was looking at and he responded with “you’re the guy who put the wanted poster up correct? – well your turtle is standing next to the poster… it’s the same turtle”. Now I was excited. We did some surveys in that area and in 2007 saw our first terrapin! I can’t tell you how exciting it was. Two years of searching… at times thinking we might work on another project with a different species that actually exists… reading that the diamondback terrapin is like the Loch Ness monster – everyone talks about them, but no one has ever seen one. And there it was, a track in the sand and a head in the water. Yes Virginia… terrapins do exist in the Florida panhandle. The excitement of finding one was indescribable.

We were hooked. We now had to look in other counties in the panhandle, and yes, we found them. As I watched the program of the marine mammologists searching for “52” I could completely relate.

Today, as a marine educator with Florida Sea Grant, I train others how to do terrapin surveys and searches. I let them know how hard it is to find them and to not get disappointed. When they do see one, it will be a very exciting and fulfilling day. Our citizen science program has expanded to searching for other elusive creatures in our bay area. Bay scallops, which are all but gone however we do find evidence of their existence and spend time each year searching for them. In the five years we have been searching we have found only one live scallop, but we are sure they are there. We find their cleaned shells on public boat ramps – by the way, it is illegal to harvest bay scallops in the Pensacola Bay area. Another we are searching for is the nesting beaches of the horseshoe crabs. This is another animal that basically disappeared from our waters but are occasionally seen now. It is exciting to find one, but we are still after their nesting beaches and the chase is on.

Bay Scallop Argopecten irradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

Horseshoe crabs breeding on the beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

I love the challenge of searching for such creatures. If you do as well, we have a citizen science program that does so. You can just contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office to get on the training list, trainings occur in March, and we will get you out there searching. As for whether they found “52”, you will have to watch the program 😊

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 17, 2021

EDRR Invasive Species

Black and White Argentine Tegu

(Salvator merianae)

The Argentine Black and White Tegu.

Photo: EDDMapS.org

Define Invasive Species: must have all of the following –

- Is non-native to the area, in our case northwest Florida

- Introduced by humans, whether intentional or accidental

- Causing either an environmental or economic problem, possibly both

Define EDRR Species: Early Detection Rapid Response. These are species that are either –

- Not currently in the area, in our case the Six Rivers CISMA, but a potential threat

- In the area but in small numbers and could be eradicated

Native Range:

The Argentine Black and White Tegu is native to South America.

Introduction:

The tegu was introduced to Florida through the pet trade. Some animals either escaped or were released.

EDDMapS currently list 7,014 records of the Argentine Black and White Tegu in the U.S. 5,908 (84%) are from Miami-Dade County. There are 12 records from Georgia and one from Memphis Tennessee. The majority of records are from south Florida.

There are 12 records from the Florida panhandle and five within the Six Rivers CISMA. The only confirmed breeding pairs are in Miami-Dade, Hillsborough, and Charlotte counties in Florida.

Description:

Tegus are long black and white banded lizards that can reach four feet in length. They prefer high dry sandy habitats but can be found in a variety of habitats including agricultural fields.

Issues and Impacts:

Basically… they eat everything. Being omnivores, stomach analysis indicates they will feed on fruits, vegetables, eggs, insects, and small animals. These animals include lizards, turtles, snakes, lizards, and small mammals. They feed primarily on ground dwelling creatures. A typical tegu clutch will have 35 eggs.

The consumption of fruits and vegetables can have a major impact on agricultural row crops throughout Florida. Their habit of consuming eggs would include the American alligator, the American crocodile, and the gopher tortoise – all protected species.

Records show the number of tegus trapped each year is growing, with over 1400 captured in 2019. This suggests the populations are increasing and new breeding colonies are probable. There are also records of the animal in north Florida and Georgia, suggesting they can tolerate the colder winters of those regions.

Management:

Management is currently with trapping. Both the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission and their subcontracted trappers are currently the primary method of removing the animals. Researchers from the University of Florida as well as those mentioned above frequently conduct roadside surveys searching for these animals. We ask anyone who has seen a tegu to report it on the IveGotOne App found on the EDDMapS website – www.eddmaps.org – or the website itself, and call your local extension office.

For more information on this EDRR species, contact your local extension office.

References

Control of Invasive Tegus in Florida. The Croc Docs. https://crocdoc.ifas.ufl.edu/projects/Argentineblackandwhitetegus/

Harvey, R.G., Dalaba, J.R., Ketterlin, J., Roybal, A., Quinn, D., Mazzotti, F.J. 2021. Growth and Spread of the Argentine Black and White Tegu Population in Florida. University of Florida IFAS Electronic Data Information System. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/publication/UW482

Harvey, R.G., Mazzotti, F.J. 2015. The Argentine Black and White Tegu in South Florida; Population, Spread, and Containment. University of Florida IFAS Publication WEC360.

https://crocdoc.ifas.ufl.edu/publications/factsheets/tegufactsheet.pdf

Johnson, S.A., McGarrity, M. 2020. Florida Invader: Tegu Lizard. University of Florida Wildlife Ecology Conservation. WEC295. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdf/UW/UW34000.pdf

Early Detection and Distribution Mapping System (EDDMapS)

https://www.eddmaps.org/

Six Rivers CISMA

https://www.floridainvasives.org/sixrivers/