by Rick O'Connor | Feb 5, 2020

This is one of the most beloved animals on the planet… sea turtles. Discussions and debates over all sorts of local issues occur but when sea turtles enter the discussion, most agree – “we like sea turtles”, “we have nothing against sea turtles”. There are nonprofit groups, professional hospitals, and special rescue centers, devoted to helping them. I think everyone would agree, seeing one swimming near the shore, or nesting, is one of the most exciting things they will ever see. For folks visiting our beaches, seeing the white sand and emerald green waters is amazing, but it takes their visit to a whole other level if they encounter a sea turtle.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

They are one of the older members of the living reptiles dating back 150 million years. Not only are they one of the largest members of the reptile group, they are some of the largest marine animals we encounter in the Gulf of Mexico.

There are five species of marine turtles in the Gulf represented by two families. The largest of them all is the giant leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea). This beast can reach 1000 pounds and have a carapace length of six feet. Their shell resembles a leatherjacket and does not have scales. Because of their large size, they can tolerate colder temperatures than other marine turtles and found all over the globe. They feed almost exclusively on jellyfish and often entangled in open ocean longlines. There is a problem distinguishing clear plastic bags from jellyfish and many are found dead on beaches after ingesting them. Like all sea turtles, they approach land during the summer evenings to lay their eggs above the high tide line. The eggs incubate within the nest for 65-75 days and sex determination is based on the temperature of the incubating eggs; warmer eggs producing females. Also, like other marine turtles, the hatchlings can be disoriented by artificial lighting or become trapped in human debris, or unnatural holes, on the beach. These animals are known to nest in Florida and they are currently listed as federally endangered and are completely protected.

The large head of a loggerhead sea turtle.

Photo: UF IFAS

The other four species are found in the Family Chelonidae and have the characteristic scaled carapace. Much smaller than the leatherback, these are still big animals. The most common are the loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). As the name suggest, the head of this sea turtle is quite large. Their carapace can reach lengths of four feet and they can weigh up to 450 pounds. The head usually has four scutes between the eyes and three scutes along the bridge connecting the carapace to the plastron. This animal prefers to feed on a variety of invertebrates from clams, to crabs, to even horseshoe crabs. It too is an evening nester and the young have similar problems as the leatherback hatchlings. The tracks of the nesting turtle can be identified by the alternating pattern made by the flippers. One flipper first, then the next. The loggerhead is currently listed as a federally threatened species.

A green sea turtle on a Florida beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) is called so not for the color of its shell, but for the color of its internal body fat. They are fans of eating seagrasses, particularly “turtle grass” and other plants, which produce the green coloration of the fat. The fat is used to produce a world favorite, “turtle soup”, and has been a problem for the conservation of this species in some parts of the world. At one time, most green turtles nested in south Florida, but each year the number nesting in the north has increased. They can be distinguished from the loggerhead in that (1) their head is not as big, (2) there are only two scales between the eyes, and (3) their flipper pattern in sand is not alternating; green turtles throw both flippers forward at the same time. Green turtles are listed as federally threatened.

A hawksbill sea turtle resting on a coral reef in the Florida Keys.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is more tropical in distribution. They are a bit smaller, with a carapace length of three feet and a weight of 187 pounds, but their diet of sponges is another reason you do not find them often in the northern Gulf of Mexico. To feed on these, they have a “hawks-bill” designed to rip the sponges from their anchorages. Their shell is gorgeous and prized in the jewelry trade. “Tortoise-shell” glasses and earrings are very popular.

The most endangered of them all is the small Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). This little guy has a carapace length of a little over two feet and weighs in at no more than 100 pounds. These guys are commonly seen in the Big Bend area of Florida but for years no one knew where they nested. That was until 1947 when an engineer from Mexico found them nesting in large numbers (up to 40,000) at one time, in broad daylight in Rancho Nuevo, Mexico. This was problematic for the turtle because the locals would wait for the nesting to be complete before they would take the females and the eggs. Protected today they now face the problem that their migratory path across the Gulf takes them through Texas and Louisiana shrimping grounds, and through the 2010 Deep Water Horizon oil spill field. Not to mention that illegal poaching still occurs. Though all species of sea turtles have had problem with shrimp trawls, the Kemps had a particular problem, which led to the develop of the now required Turtle Excluder Device (T.E.D.S) found on shrimp trawls in the U.S. today. Sea turtles have strong site fidelity for nesting and in the 1980s many Kemp’s Ridley eggs were re-located to beaches in Texas in hopes to move the nesting to other locations. The program had some success and they have been reported to nest in Florida. Their diet consists primarily of crabs but there have been reports of them removing bait from fishing lines fishing from piers over the Gulf. This is species is federally endangered and is considered by many to be the most endangered sea turtle species on the planet.

Turtle friendly lighting.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Sea turtles face numerous human-caused problems including (1) artificial lighting that disorient hatchlings and cause mortality to 50% (or more) of the hatchlings, (2) items left on beaches (such as chairs, tents, etc.) that can impede adults and entrap hatchlings, (3) large holes dug on beaches in which hatchlings fall and cannot get out, (4) marine debris (such as plastics) which they confuse with prey and swallow, (5) boat strikes, sea turtles must surface to breath and can become easy targets, and (6) discarded fishing gear, in which they can become entangled and drown. These are simple things we can correct and protect these amazing Florida turtles.

References

Buhlmann, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 252.

Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species. 2018. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/media/1945/threatend-endangered-species.pdf,

Species of Sea Turtle Found in Florida. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/florida/species/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 29, 2020

If you ask a kid who is standing on the beach looking at the open Gulf of Mexico “what kinds of creatures do you think live out there?” More often than not – they would say “FISH”.

And they would not be wrong.

According the Dr. Dickson Hoese and Dr. Richard Moore, in their book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, there are 497 species of fishes in the Gulf. However, they focused their book on the fish of the northwestern Gulf over the continental shelf. So, this would not include many of the tropical species of the coral reef regions to the south and none of the mysterious deep-sea species in the deepest part of the Gulf. Add to this, the book was published in 1977, so there have probably been more species discovered.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski

Fish are one of the more diverse groups of vertebrates on the planet. They can inhabit freshwater, brackish, and seawater habitats. Because all rivers lead to the sea, and all seas are connected, you would think fish species could travel anywhere around the planet. However, there are physical and biological barriers that isolate groups to certain parts of the ocean. In the Gulf, we have two such groups. The Carolina Group are species found in the northern Gulf and the Atlantic coast of the United States. The Western Atlantic Group are found in the southern Gulf, Caribbean, and south to Brazil. The primary factors dictating the distribution of these fish, and those within the groups, are salinity, temperature, and the bottom type.

Off the Texas coast there is less rain, thus a higher salinity; it has been reported as high 70 parts per thousand (mean seawater is 35 ppt). The shelf off Louisiana is bathed with freshwater from two major rivers and salinities can be as low as 10 ppt. The Florida shelf is more limestone than sand and mud. This, along with warm temperatures, allow corals and sponges to grow and the fish assemblages change accordingly.

Some species of fish are stenohaline – meaning they require a specific salinity for survival, such as seahorses and angelfish. Euryhaline fish are those who have a high tolerance for wide swings in salinity, such as mullet and croaker.

Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant. In total, it takes about 3 – 5 years for reefs to reach a level of maximum production for both fish and invertebrate species.

Forty-three of the 497 species are cartilaginous fish, lacking true bone. Twenty-five are sharks, the other 18 are rays. Sharks differ from rays in that their gill slits are on the side of their heads and the pectoral fins begins behind these slits. Rays on the other hand have their gill slits on the bottom (ventral) side of their body and the pectoral begins before them. Not all rays have stinging barbs. The skates lack them but do have “thorns” on their backs. The giant manta also lacks barbs.

Sharks are one of the more feared animals on the planet. 13 the 25 species belong to the requiem shark family, which includes bull, tiger, and lemon sharks. There are five types of hammerheads, dogfish, and the largest fish of all… the whale shark; reaching over 40 feet. The most feared of sharks is the great white. Though not believed to be a resident, there are reports of this fish in the Gulf. They tend to stay offshore in the cooler waters, but there are inshore reports.

The impressive jaws of the Great White.

Photo: UF IFAS

There is great variety in the 472 species of bony fishes found in the Gulf. Sturgeons are one of the more ancient groups. These fish migrate from freshwater, to the Gulf, and back and are endangered species in parts of its range. Gars are a close cousin and another ancient “dinosaur” fish. Eels are found here and resemble snakes. As a matter of fact, some have reported sea snakes in the Gulf only to learn later they caught an eel. Eels differ from snakes in having fins and gills. Herring and sardines are one of the more commercially sought-after fish species. Their bodies are processed to make fish meal, pet food, and used in some cosmetics. There are flying fish in the Gulf, though they do not actually fly… they glide – but can do so for over 100 yards. Grouper are one of the more diverse families in the Gulf and are a popular food fish across the region. There untold numbers of tropical reef fish. Surgeons, triggerfish, angelfish, tangs, and other colorful fish are amazing to see. Stargazers are bottom dwelling fish that can produce a mild electric shock if disturbed. Large billfish, such as marlins and sailfins, are very popular sport fish and common in the Gulf. Puffers are fish that can inflate when threatened and there are several different kinds. And one of the strangest of all are the ocean sunfish – the Mola. Molas are large-disk shaped fish with reduced fins. They are not great swimmers are often seen floating on their sides waiting for potential prey, such as jellyfish.

We could go on and on about the amazing fish of the Gulf. There are many who know them by fishing for them. Others are “fish watchers” exploring the great variety by snorkeling or diving. We encourage to take some time and visit a local aquarium where you can see, and learn more about, the Fish of the Gulf.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press. College Station Texas. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 21, 2020

There are a couple of things you learn when working with youth in turtle education.

1) ALL turtles are snapping turtles

2) Snapping turtles are dangerous

I grew up in a sand hill area of Pensacola and we found box turtles all of the time. We had one as a “pet” and his name was “Snappy”. Oh, I forgot… all turtles are males.

That said, others are well aware of this unique species of turtle in our state. It does not look like your typical turtle. (1) They are large… can be very large – some male alligator snappers have weighed in at 165 lbs.! (2) Their plastron is greatly reduced, almost not there. Because of this their legs can bend closer to the ground and walk more like dogs than other turtles do. We call this cursorial locomotion. Snappers are not cursorial, but they are close, and because of this can move much faster across land. (3) Their carapace is almost square shaped (versus round or oval) and have large ridges making them look like dinosaurs. (4) They have longer tails than most turtles, some species have scales pointing vertically making them look even more like dinosaurs. Scientists have wondered whether this unique reduced plastron-better locomotion design was the original for turtles (and they lost it), or they are the “new kids on the block”. The evidence right now suggests they are “the new kids”.

The relatively smooth shell of a common snapping turtle crossing a highway in NW Florida.

Photo: Libbie Johnson

And of course, there is the “SNAP”. These are very strong animals who seem to crouch and lunge as they quickly SNAP at potential predators – as quickly as 78 milliseconds/bite. I remember once stopping on a rural highway to get one out of the road. I grabbed it safely behind the nape and near the rear. That sucker crouched and snapped, and I could hardly hold on. I was amazed by its strength. It did not understand I was trying to help. You do need to be careful around these guys.

In Florida, we have two species of snapping turtles; the common and the alligator. They look very similar and are often confused (everyone seen is called an alligator snapper). There are couple of ways to tell them apart.

1) The alligator snapper has a large head with a hooked beak.

2) The alligator snapper’s carapace is slightly squarer and has three ridges of enlarged scales that make it look “spiked”; where the common snapper lacks these.

3) The tail of the common snapper has vertical “spiked” scales; which the alligator lacks.

4) And the textbook range of the alligator snapper is the Florida panhandle. Basically, if you are south or east of the Suwannee River, it should not be around – you are seeing the common.

As the name implies, the common snapper (Chelydra serpentina) is found throughout the state – except the Florida Keys. There are actually two subspecies; the Common (C. serpentia serpentina) which is found west of the Suwannee River and the Florida Snapper (C. serpentina osceola). This species uses a wide range of habitats. They have been found in small creeks, ponds, floodplain swamps, wet areas of pine flatwoods, and on golf courses.

These are very mobile turtles, often seen crossing highways looking for nesting locations, dispersing to new territory, or their pond has just dried up and they need a new one. Interestingly they have an expanded diet. Most think of snapping turtles as fish eaters, but common snappers are known to consume large amounts of aquatic plants and invertebrates.

Like all turtles, snappers must find high-dry ground for nesting. Nesting begins around April and runs through June. In south Florida, nesting can begin as early as February. They select a variety of habitats and typically lay 2-30 eggs deep in the substrate. These incubate for about 75 days and the temperature of the egg determines its sex; warmer eggs produce females. Nest predation is a problem for all turtles, snappers are not exempt from this. Raccoons are the big problem, but fish crows, fox, and possibly armadillos also dig up eggs. Many adults have been found with leeches. Turtles are known to live long lives. Data suggests common snappers reach 50 years of age.

Alligator snappers (Macrochelys temminckii) are the big boys of this group. Where the common snapper’s carapace can reach 1.5 feet, the alligator snapper can reach 2.0. (that’s JUST the shell). As mentioned, this animal is found in the Florida panhandle only. It is a river dweller and prefers those with access to the Gulf of Mexico. They appear to have some tolerance of brackish water. One alligator snapper near Mobile Bay AL had barnacles growing on it. Evidence suggest they do not move as much as common snappers and stay in the river systems where they were born. There are three distinct genetic groups: (1) the Suwannee group, (2) the Ochlocknee/Apalachicola/Choctawhatchee group, and (3) the Pensacola Bay group.

The ridged backs of the alligator snapping turtle. Photo: University of Florida

This animal is more nocturnal than their cousin and are not seen very often. They are basically carnivores and known to feed on fish, invertebrates, amphibians, birds, small mammals, reptiles, small alligators, and acorns are common in their guts. This species possesses a long tongue which they use as a fishing lure to attract prey.

Alligator snappers have a much shorter nesting season than most turtles; April to May. And, unlike other turtles, only lay one clutch of eggs per season. They typically lay between 17-52 eggs, sex determination is also controlled by the temperature of the incubating egg, and they may have strong site fidelity with nesting. Male alligators are very aggressive towards each other in captivity. This suggests strong territorial disputes occur in the wild. These live a bit longer than common snappers; reaching an age of 80 years.

Though still common, both species have seen declines in their populations in recent years. Dredge and fill projects have reduced habitat for the common snapper. Dams within the rivers and commercial harvest have impacted alligator snapper numbers. The alligator snapper is currently listed as an imperiled species in Florida and is a no-take animal (including eggs). Because the common snapper looks so similar, they are listed as a no-take species as well.

Both of these “dinosaur” looking creatures are amazing and we are lucky to have them in our backyards.

References

Meylan P.A. (Ed). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

FWC – Freshwater Turtles

https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 14, 2020

Standing on one of our local beaches, the Gulf of Mexico appears to be a wide expanse of emerald green and cobalt blue waters. We can see the ripples of offshore waves, birds soaring over, and occasionally dolphins breaking the surface. But few of us know, or think, about the environment beneath the waves where 99% of the Gulf lies. We might dream about catching some of the large fish, or taking a cruise, but not about the geology of the bottom, what the water is doing beneath the waves, or what other creatures might live there.

The Gulf of Mexico as seen from Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

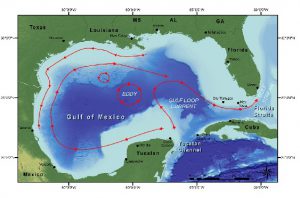

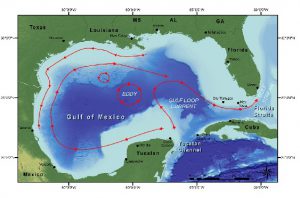

Scanning the horizon from the beach, you are gazing at 600,000 square miles of open water. It is about 950 miles from the panhandle to Mexico. Traveling at 10 knots, it would take you about 3 days to cross at its widest point. The Gulf is almost an enclosed body of water. The bottom is somewhat “bowl” shaped with the deepest portion slightly west of center at a location known as the Sigsbee Deep. The island of Cuba serves as the “median” between where the ocean enters and exits the Gulf. Cycling water from the Atlantic crosses from Africa, through the Caribbean, and enters the between Cuba and the Yucatan. The seafloor here sinks and spills into the Sigsbee Deep. The pass between Cuba and Yucatan is about 6500 feet deep and the bottom of the Sigsbee Deep is about 12,000. If you are looking due south from the Florida Panhandle, you would be looking at this pass.

If your gaze shifted slightly to the right – maybe “1:00” – you would be looking at the Yucatan. The Yucatan itself forms a peninsula and a portion of it is below sea level extending further into the Gulf. This submerged portion of the Yucatan is what oceanographers refer to as a continental shelf. On the “leeward” side of the Yucatan Peninsula lies an area of the Gulf known as the Bay of Campeche. There is a shallow section of this “bay” known as the Campeche Banks which supports amazing fisheries and some mineral extraction. Off the Yucatan shelf there is a current of water that rises from the ocean floor called an upwelling. These upwellings are usually cold water, high in oxygen, and high in nutrients – producing an area of high biological productivity and good fishing.

Continuing to circle the Sigsbee Deep and looking about “2:00”, northwest of the Bay of Campeche, you enter the western Gulf which extends from Vera Cruz Mexico to the Rio Grande River in Texas. The shelf is much closer to shore here and the marine environment is still tropical. There is a steep continental slope that drops into the Sigsbee Deep. Water from the incoming ocean currents usually do not reach these shores, rather they loop back north and east forming the Loop Current. The shelf extends a little seaward where the Rio Grande discharges, leaving a large amount of sediment. In recent years, due to human activities further north, water volume discharge here has decreased.

In the direction of about “2:30”, is the Northwestern Gulf. It begins about the Rio Grande and extends to the Mississippi Delta. Here the continental shelf once again extends far out to sea. One of the larger natural coral reefs in the Gulf system is located here; the Flower Gardens. This reef is about 130 miles off the coast of Texas. The cap is at 55 feet and drops to a depth of 160 feet. Because of the travel distance, and diving depth, few visit this place. Fishing does occur here but is regulated. This shelf is famous for billfishing, shrimping, and fossil fuel extraction. The Mississippi River, 15th largest in the world and the largest in the Gulf, discharges over 590,000 ft3 of water per second. The sediments of this river create the massive marshes and bayous of the Louisiana-Mississippi delta region, which has been referred to as the “birds’ foot” extending into the Gulf. This river also brings a lot of solid and liquid waste from a large portion of the United States and is home to one of the most interesting human cultures in the United States. There is much to discuss and learn about from this portion of the Gulf over this series of articles.

The basin of the Gulf of Mexico showing surface currents.

Image: NOAA

At this point we have almost completely encircled the Sigsbee Deep and move into the eastern Gulf. Things do change here. From the Mississippi delta to Apalachee Bay west of Apalachicola is what is known as the Northeastern Gulf – also known as the northern Gulf – locally called the Gulf coast. This is home to the Florida panhandle and some of the whitest beaches you find anywhere. Offshore the shelf makes a “dip” close to the beach near Pensacola forming a canyon known as the Desoto Canyon. The bottom is a mix of hardbottom and quartz sand. Near the canyon is good fishing and this area, along with the Bay of Campeche, is historically known for its snapper populations. It lies a little north of the Loop Current but is exposed to back eddies from it. Today there is an artificial reef program here and some natural gas platforms off Alabama.

Looking between “9:00-10:00” you are looking at the west coast of Florida and the Florida shelf. Here the shelf extends for almost 200 miles offshore. Off the Big Bend the water is shallow for miles supporting large meadows of seagrass and a completely different kind of biology. The rock is more limestone and the water clearer. In southwest Florida the grassflats support a popular fisheries area and a coral system known as the Florida Middle Grounds. At the edge of the shelf is a steep drop off called the Florida Escarpment, which forms the eastern side of the “bowl”. Another ocean upwelling occurs here.

Looking at “11:00” you are looking towards the Florida Keys. Between the Keys and Cuba is the exit point of the Loop Current called the Florida Straits. It is not as deep as here as it is between Cuba and the Yucatan; only reaching a depth of 2600 feet. This is mostly coral limestone and the base of one of the largest coral reef tracks in the western Atlantic. The coral and sponge reefs, along with the coastal mangroves, forms one of the more biological productive and diverse regions in our area. It supports commercial fishing and tourism.

We did not really talk about the bottom of the “bowl”. Here you find remnants of tectonic activity. Volcanos are not found but you do find cold and hot water vent communities, which look like chimneys pumping tremendous amounts of thermal water from deep in the Earths crust. These vent communities support a neat group of animals that we are just now learning about. Brine lakes have also been discovered. These are depressions in the seafloor where VERY salty water settles. These “lakes” have water much denser than the surrounding seawater and can even create their own waves. Many of them lie as deep as 3300 feet and can be 10 feet deep themselves. There is one known as the “Jacuzzi of Despair”. They are so salty they cannot support much life.

In the next addition to this series we will begin to look at the some of the interesting plant and animals that call the Gulf home.

Embrace the Gulf.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 10, 2020

It’s an amazing place really – the Gulf of Mexico. Covering over 598,000 square miles this almost a complete circle of water and home to some interesting geological features, amazing marine organisms, some of busiest ports in the United States, offshore mineral extraction, great vacation locations, and amazing local culture.

View from the Navarre Beach pier Photo credit: Lydia Weaver

As you stand along Pensacola Beach and look south, you see a wide expanse of water that seems to go on forever. However, in oceanographic terms, the Gulf is not that large of a body of water. Though it is close to 600,000 square miles in size, the Atlantic Ocean is 41,000,000 and the Pacific is 64,000,000 square miles. In addition to area, the mean depth of the Atlantic is a little over 12,000 feet and the Pacific is 14,000 feet. In comparison, the deepest point of the Gulf is 14,000 feet and the mean depth is only 5,000. The shape of the bottom is like a ceramic bowl that was not centered well when fired. The deepest point, the Sigsbee Deep, is about 550 miles southwest (about “2:00” if you are looking from the beach). The shape appears like a hole made by a golf ball that landed in a sand trap. As a matter of fact, there are scientists who believe this is exactly what happened – a large asteroid or comet made have hit the Earth near the Gulf forming a large series of tsunamis and created the Gulf as we know it today.

Either way the “pond” (as some oceanographers refer to it) is an amazing place. The bottom is littered with hot vents, brine lakes, and deep-sea canyons. Large areas of the continental shelf support coral reef formation and a great variety of marine life. Some of the busiest ports in the United States are located along its shores, and it supplies 14% of the wild domestic harvested seafood. Everyone is aware of the mineral resources supplied on the western shelf of the Gulf and the tremendous tourism all states and nations that bordering enjoy.

The emerald waters of the Gulf of Mexico along the panhandle.

This year the Gulf of Mexico Alliance will be celebrating “Embracing the Gulf” with a variety of activities and programs across the northern Gulf region. We will be dedicating this column to articles about the Gulf of Mexico all year and discussing some of the topics mentioned above in more detail. We hope you enjoy your time here and get a chance to explore the Gulf’s seafood, fishing, diving, marine life, ship cruises, unique cultures, and awesome sunsets. Embrace the Gulf!