by Rick O'Connor | Sep 20, 2015

Yea, seafood… who doesn’t like seafood… actually, based on a small scale survey I conducted with marine science students over the last 28 years I have found a slight increase in the number of those who do not. Curious about this, I followed up by asking whether their concern was seafood safety or other. Almost all said they just did not like the taste. Okay… I can take that… there are something I do not like either BUT I LIKE SEAFOOD. The survey also showed that almost every year with young/old or male/female – shrimp was at the top of their favorite list. After shrimp the next 3-4 choices for males was some type of fish. For females it varied – fish, lobster, calamari, to name a few.

Shrimping depends on healthy estuaries.

Photo: NOAA

So what does this have to do with estuaries…

Well, you may not know this but 90% of the commercial important marine species require estuaries for at least part of their life cycles. Just as humans select a neighborhood to live and raise their kids based on safety and schools – “fish parents” find everything they want for their “kids” in an estuary. They are shallow – allowing light to reach much of the bottom where submerged plants, like seagrasses, can grow. These seagrasses provide hiding places and a place for small algae to attach – which is an important food source for many of them. There are other places for them to hide as well – emergent salt marshes and oyster reefs are biologically very productive habitats. Many of the developing larva and juveniles require lower salinities to begin and complete their life cycles; venturing to the open Gulf only when they have developed a tolerance for the higher salinities. The freshwater discharge not only lowers the salinity it also brings nutrients. These nutrients, along with the sunlight reaching much of the water column, produce an abundance of microscopic plankton – food for the young. The nutrients, thermal mixing, low salinities, and variety of habitats provide a combination for one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on the planet – a great place to grow up… and much of it we enjoy eating.

Most of what we consume in the seafood world is divided into shellfish and finfish. Some of it is harvested and sold commercially, some we collect recreationally. In the shellfish world we are talking mollusk and crustaceans – two of the most popular seafood groups on the planet. The mollusk include snails, oysters, clams, mussels, scallops, and cephalopods like squid and octopus. Many of these species live in our estuaries their entire life cycle. Most are slow moving creatures – if they move at all – and have provided a living for some humans, recreation for many, for decades – though the landings of these species are on the decline… more on this in a later issue.

Oysters are one of the more popular shellfish along the panhandle.

Photo: FreshFromFlorida

Crustaceans include the ever popular gulf shrimp. We actually have three different species of bay shrimp we like – white, brown, and pink shrimp. There are other varieties found offshore we are now consuming, but these have been the big three. Blue crab – my personal favorite – is another popular crustacean. Though these are still harvested commercially, “crabbing” with your kids is a long time popular panhandle activity – and the day always ends well with a great meal. Crustaceans are more mobile and conduct small migrations during their life cycles. Shrimp develop within the estuary and then move offshore for breeding where the incoming tide brings the larva back to the estuary. Blue crabs migrate to the head of the bay for breeding and the females return to the lower end of the estuary for egg development and larva release – they may enter the Gulf during this process but tend to stick to the bays for the entire cycle.

The famous Gulf Coast shrimp.

Photo: Mississippi State University

In the finfish world we are talking drum, snapper, grouper, trout, whiting, mullet, flounder, sheepshead, and many more. These species have provided both a living for the commercial fishermen and recreation for families for years. Many species breed and grow within the estuary while others make trips in and out of the bay to complete their cycles. In addition to commercial and family recreation charter fishing has increased as a business along the Gulf coast.

One of the more popular finfish – the grouper.

Photo: Bay County Extension, UF IFAS

We hope you and your family enjoy local seafood from our bays. There are several websites and apps, such as Seafood@Your Fingertips, that can help you locate local seafood – or you can go catch some yourselves! If harvesting recreationally be reminded that there are regulations and licenses required. You can read more about those at MyFWC.com.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 19, 2015

Welcome to National Estuaries Week! Each year in the fall NOAA and other agencies try to educate residents about estuaries. The vast majority of humans on our planet live on, or near, an estuary – many not realizing the importance those bodies of water have on our economy and quality of life. We live on them, consume food from them, swim in them, recreate on them, and maybe make your living from them. They are an integral part of our lives and many are under stress. Over the next seven days we will post articles discussing some of the benefits and problems our local estuaries are having. Let’s begin with What is an Estuary?

An estuary… where rivers meet the sea.

Photo: University of California.Berkley

Estuaries are defined as semi-enclosed bodies of water where fresh and salt water mix. Typically freshwater enters at the head of the bay. In the Florida panhandle most of our estuaries are fed by one of two types of rivers; alluvial and tannic. Alluvial rivers are large, fast flowing streams that begin far up in the watershed (Georgia or Alabama) and typically are quite muddy; Escambia, Choctawhatchee, and Apalachicola Rivers are examples.

Tannic rivers are generally smaller in size, flow slower over coastal flatwoods, and build up tannins from the decomposition of leaf litter that settles to the bottom due to the slow currents. Due to the high levels of tannin, these rivers general have a lower pH and “blackwater” “ice tea” coloration to them; Blackwater and Perdido Rivers are examples.

Freshwater from these rivers is less dense than seawater and tends to flow across the surface of the bay towards the mouth of the bay; where it meets the Gulf of Mexico. There are several types of estuaries found around the world and the ones in our area are drowned river valleys. They formed when ice from the last glacial period melted and flowed towards the sea. As they reached the coast areas of “low land” filled with water and became bays. Drowned river valleys typically are very wide and very shallow. Mobile Bay is 35 miles long, 10 miles wide, and not much deeper than 11 feet across its area. I remember as a kid scalloping in St. Joe Bay and being able to stand up at distance from shore that I could barely make out my car!

The Escambia River. One of the alluvial rivers of the Florida panhandle.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

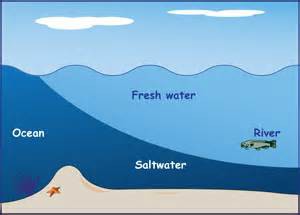

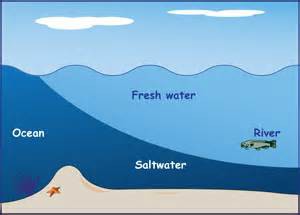

As seawater enters the bay it tends to remain near the bottom and will “finger” it’s way towards the head forming two layers of water within the bay; freshwater on top – seawater on the bottom. This “fingering” movement is called a salt wedge and forms a halocline which impacts the distribution and diversity of aquatic species. On windy days the top and bottom layers will mix and the salinity of the bay becomes more brackish with no noticeable halocline; this too will impact the diversity and distribution of aquatic life. Creatures who live in estuaries must be hardy and prepared for drastic environmental change over the course of the day.

In the Florida panhandle our estuaries experience diurnal tides; 1 high and 1 low tide each day. The incoming tides are generally weaker than the outgoing ones; I have, more than once, been caught in an outgoing tide in Pensacola Bay… VERY difficult to swim out of.

A salt wedge.

Graphic: NOAA

We have seven estuarine systems along the Florida panhandle; Perdido, Pensacola, Choctawhatchee, St. Andrew’s, St. Joseph, Apalachicola, and the Apalachee. Each is unique and important to their communities and provide benefits that are truly priceless. Enjoy the other articles we will post during National Estuaries Week and GO OUT AND ENJOY YOUR ESTUARY! It’s the perfect time of year for it.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 19, 2015

Most of us remember the string of shark attacks that occurred this past summer in North Carolina; as a matter of fact, according to the International Shark Attack File, it was a record year for that region. Since 2001 there have been 34 shark attacks in North Carolina ranging from 1-5 per year (average 2.4 attacks / year); this year there were 8 attacks. Why the increase?

Reviewing the trend data we can see that the human population has increased, attendance at local beaches has increased, the number of tourists to our beaches has increased, and the shark attacks have also increased. But could the actual number of sharks be increasing as well? A recent report suggest… maybe.

Pregnant Bull Shark (Carcharhinus leucas) cruses sandy seafloor. Credit Florida Sea Grant Stock Photo

Since 1986 NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center has been capturing and logging sharks along the southeast coast of the United States. This year’s survey logged 2,835 sharks between North Carolina and Florida; most were Sandbar’s, Atlantic Sharpnose, Dusky, and Tiger sharks. This is an increase from 1,831 in 2012 and higher than any year since the surveys began.

Are they getting better at catching shark? Maybe… but scientific surveys require that the team use the same protocol each year when conducting such surveys, suggesting that there are in fact more sharks out there. If this is so, why are there more sharks?

Well you first have to confirm that this is in fact the case – sharks are in fact increasing. But scientists can begin looking at data that could explain it. Typically you would begin with their food supply and predation. Though we now know that increase in food supply does not always equate to an increase in predators, it is data that should be reviewed. And what about predators of sharks? Which is typically us.

A review of the NOAA shark landing data indicates that 5 of the 9 shark categories have been closed as of June 22, 2015 because they have landed a significant percentage of their allowed quota for the year. This equates to good fishing… which could mean more sharks. Discussing with local divers in the Pensacola area, they believe they are seeing more sharks – and the increase seems to be closer inshore. It is an El Nino year, and environmental conditions change during these seasons. It is known that environmental changes will certainly trigger changes in fishery numbers and distribution.

As the scientific process works itself out, we will learn more about what is occurring with sharks in U.S. waters. In our state the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission protects 25 species of sharks. Anglers are allowed one non-protected species and no more than 2 per vessel. (Learn More). More should be known once the 2015 season comes to an end. Why shark numbers in North Carolina have increased is not understood at this time but monitoring will continue.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 19, 2015

I am not going to lie… I skipped August… It was hot…

September however was nice. The day I made the hike the skies were clear and the temperature was 75°F! wonderfully… truly wonderful.

If you are like me you probably begin your day around the same time – and have probably noticed that it is darker when you get up. September 22 is the fall equinox and the length of our day will be exactly 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of darkness. We then enter the “dark side” of the calendar year – the days will become shorter… and already have. As we move into autumn on our beaches we will notice some changes. One, fewer visitors, but we will also notice changes in wildlife.

The steep incline of a winter time beach scarp.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The remnants of moon jellyfish near a ghost crab hole.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Many counties in the panhandle have lighting and barrier ordinances to protect wildlife and workers.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

As you can see in the photograph the scarp of the shoreline is becoming more pronounced. As the sun begins to spend more time below the horizon the winds shift, the waves change, sand is moved more offshore and the shape of our beach changes as well. You may have noticed the purple safety flags have been flying a lot recently. These mean “dangerous sea life” and we have been seeing a lot of jellyfish as the summer comes to a close. Today I noticed a lot of ghost crab holes. These guys are always around but their presence seems more noticeable this time of year – possibly due to more available food. Over the last six months I have been working with CleanPeace and the Escambia County Division of Marine Resources monitoring marine debris. Our objective is to determine what the major local debris issues are and develop an education program to try and reduce these problems. Cigarette butts have been consistently the #1 item since January. Many of you probably remember the “Keep Your Butt off the Beach” campaign a few years back… apparently did not worked well. We will have to educate locals and visitors to please take their cigarette butts with them. For those in Escambia County you will now notice the new Leave No Trace signs. The Escambia County Board of County Commissioners passed a new ordinance this past month that requires all residents and visitors to remove items from the beach overnight. Not only have these negatively impacted nesting sea turtles they have become a hazard for evening work crews and the general public. Most panhandle counties have some form of “Leave No Trace”. Please help educate everyone about their ordinances.

The majestic monarch butterfly stopping along the panhandle on its way to Mexico.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The common sandspur.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

A snake skeleton found near the swale area on the island. Between the primary and secondary dune.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Fall is the time of the monarch movement. Typically they begin to show in numbers after the equinox but we did see a few on the island this week. Be ready, next month should be full of them. The sandspurs were beginning to develop their spiny seed pods. I would caution all to check their shoes and clothing before leaving the beach this time of year to avoid carrying these seed pods home and distributing them in your yard… uncool.

One of the many species of dragonflies that visit our islands.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The tracks of the very common armadillo.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The invasive Chinese Tallow.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

We did see evidence of snake movement this week. There are several species, including the Eastern Diamondback Rattler, which will breed in the fall as well as the spring. I expect to see more activity as the days grow shorter. The dragonflies were very active this month. Actually my wife witnessed two of them consistently pestering a monarch butterfly until the butterfly moved away. I have seen armadillo activity every month of the year so far, this month was no different. The islands seem full of them. This lone Chinese Tallow has formed a small dune where other plants have established and many creatures have taken up residence. At this time there are no other Tallow in the area, and this one will need to be removed before the spread begins. But it is an interesting paradox in that there was an armadillo burrow found here and the sea oats have utilized this dune as well. Invasive species are a problem throughout the state and many have caused with economic or environmental problems – or both! Though this tree has participated in establishing a much needed dune on our hurricane beaten island – native plants do the same and should be favored over non-native. We will have to remove this tree.

An unknown track; possibly of a turtle hatching.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

This tick was a hitchhiker on our trip through the dunes.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

This track was found in the tertiary dune system and could be an adult turtle.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This small track has the appearance of a “turtle crawl”. It certainly is not a sea turtle, in the middle of the dune field for one thing, but there are several freshwater ponds on our islands that harbor a variety of “riverine turtles”. I know that Cooters, Sliders, and Snappers live on Santa Rosa Island. Terrapins are found in salt marshes. Not sure if this is a turtle but all should be aware that now is hatching time. Many turtle nests began hatching about a month ago and young turtles can be found in a lot of locations. The track in this picture is from a very small animal.

Ticks… yep ticks… It is hard to do a lot of fun outdoor activity in the southeast without encountering these guys. They like to sit on top of tall grass and wait for a mammal to come rummaging through. After each hike we always do a “tick check”. I typically wash my hiking clothes AS SOON AS I GET HOME – in case they are harboring within… I would recommend you do the same. We have been following the “mystery track” since January. This “bed” we have seen each month is in the same location. I thought I had solved the mystery in July when I found armadillo tracks all around it but this month suggest this is not an armadillo. We are not sure what it is – we are leaning towards alligator or otter (both of which can be found – and have been found – on our islands). We will continue to monitor this and hopefully find the sculptor.

The top of a pine tree within a tertiary dune.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The seagrass in the sound looked very thick and healthy this month. I have seen horseshoe crab here over the summer and Sea Grant conducted a scallop survey in Santa Rosa Sound and Big Lagoon within Santa Rosa and Escambia counties in August. We found no live scallop but plenty of dead ones – and some of that shell material was relatively “new”. Since scallops only live a year or two this is a good sign. There has been plenty of anecdotal evidence of live ones in the area. REMEMBER THAT IT IS ILLEGAL TO HARVEST SCALLOP WEST OF PORT ST. JOE AND ONLY FROM JUNE 27 TO SEPTEMBER 24 (Learn More). We will continue to conduct these surveys each summer to determine if our area would be a good candidate for a scallop restoration project.

As the days shorten and cool – I am expecting more wildlife activity to begin. Until next month.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 12, 2015

In the final segment of this 3 part series on worms we will discuss the largest, most commonly encountered members of the worm world… the Annelids.

Neredia are one of the more common polychaete worms.

Photo: University of California Berkley

Annelids differ from the other two groups of worms we have discussed in that they have segmented bodies. They are largest of the worms and the most anatomically complexed. The fluids of their coelomic cavity serve as a skeleton which supports muscle movement and increases locomotion. The annelids include marine forms called Polychaetes, the earthworms, and the leeches.

POLYCHAETES

Polychaetes are the most diverse group of annelids and most live in the marine environment. They differ from earthworms and leeches in that they have appendages called parapodia and do not possess a clitellum. In size they range from 1 mm (0.04”) to 3 m (10’) but most are around 10 cm (4”). Many species display beautiful coloration and some possess toxic spines.

There are 3 basic life forms of polychaetes; free-swimming, sedentary, and boring. The free-swimming polychaetes are found swimming in the water column, crawling across the seabed, or burrowing beneath the sediments. Some species are responsible for the “volcanoes” people see when exploring the bottom of our local bays. Most sedentary polychaetes produce tubes within which they live. Some tubes are made of elastic organic material and others are hard, stony, and calcareous. “Tubeworms” rarely leave their tubes but extend appendages from the tube to collect their food. Most feed on organic material either in the water column or on the seabed but some species collect and consume small invertebrates. There are commensal polychaetes but parasitism is rare. All polychaetes have gills and a closed circulatory system and some have a small heart. As with the other Annelids, polychaetes do have a small brain and are aware of light, touch, and smell; most species dislike light. Reproduction involves males and females who release their gametes in the water where fertilization occurs and drifting larva form.

The tube of a common tubeworm found on panhandle beaches; Diopatra.

Photo: University of Michigan

EARTHWORMS

Aside from parasitic tapeworms and leeches, earthworms are one of the more commonly recognized varieties of worms. Many folks actually raise earthworms for their gardens or for fish bait; a process known as vermiculture. Earthworms differ from polychaetes in that they do not have parapodia but DO possess a clitellum, which is used in reproduction. Though most live in the upper layers of the soil there are freshwater species within this group. They are found in all soils, except those in deserts, and can number over 700 individuals / m2. The number of earthworms within the soil is dependent on several factures including the amount of organic matter, the amount of moisture, soil texture, and soil pH. Scientists are not sure why earthworms surface during heavy rains but it has been suggested that the heavy drops hitting the ground can generate vibrations similar to those of an approaching mole; a reason many think “fiddling” for worms works. Earthworms can significantly improve soil conditions by consuming soil and adding organics via their waste, or castings. Unlike polychaetes, earthworms lack gills and take in oxygen through their skin, one reason why they most live in moist soils. Another difference between them and polychaetes is in reproduction. Aquatic polychaetes can release their gametes into the water where they are fertilized but terrestrial earthworms cannot do this. Instead two worms will entangle and exchange gametes; there are no male and females in this group. The fertilized eggs are encased in a mucous cocoon secreted by the clitellum.

LEECHES

Here is another creepy worm… leeches. Leeches are segmented, and thus annelids, and like earthworms they lack the parapodia found in polychaetes and possess a clitellum for reproduction. Most leeches are quite small, 5 cm (2”) but there is one from the Amazon that reaches 30 cm (12”). Most are very colorful and mimic items within the water, such as leaves. They differ from earthworms in that they are flatter and actually lack a complete coelomic cavity; which most annelids do have. They also possess “suckers” at the head and tail ends.

The ectoparasite we all call the leech.

Photo: University of Michigan

Leeches prefer calm, shallow water but are not fans low pH tannic rivers. If conditions are favorable their numbers can be quite high, as many as 10,000 / m2. They are found worldwide but are more common in the northern temperate zones of the planet; North America and Europe.

Some species feed by using an extending proboscis which they insert and remove body fluids, but most actually have jaws with teeth and use them to rip flesh to cause bleeding, cutting as frequently as 2 slices/second. Those with teeth possess an anesthesia that numbs the area where the bite occurs. Both those with and without teeth possess hirudin, which is an anticoagulant, allowing free-bleeding until the worm is full. Those who feed on blood tend to prey on vertebrates and most species are specific to a particular type of vertebrate. It is known they can detect the smell of a human and will actually swim towards one who is standing still in the water. It takes several hundred days for a leech to digest a full meal of blood and so they feed only once or twice a year. They remove most of the water from the blood once they swallow and require the assistance of bacteria in their guts to breakdown the proteins. They can detect day and night, and prefer to hide from the light. However when it is feeding time they are actually attracted to daylight to increase their chance of finding a host. Vibrations, scent, even water temperature (signaling the presence of warm blooded animals) can stimulate a leech to move towards a potential prey. Leeches, like earthworms, reproduce using a clitellum and develop a cocoon.

Though most find worms a disgusting group of creatures to be avoided, they are actually very successful animals and many species are beneficial to our environment. We hope you learned something from this series and will try and learn more.