by Sheila Dunning | Dec 15, 2017

According to Druid lore, hanging the plant in homes would bring good luck and protection. Holly was considered sacred because it remained green and strong with brightly colored red berries no matter how harsh the winter. Most other plants would wilt and die.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Several hollies are native to Florida. Many more are cultivated varieties commonly used as landscape plants. Hollies (Ilex spp.) are generally low maintenance plants that come in a diversity of sizes, forms and textures, ranging from large trees to dwarf shrubs.

The berries provide a valuable winter food source for migratory birds. However, the berries only form on female plants. Hollies are dioecious plants, meaning male and female flowers are located on separate plants. Both male and female hollies produce small white blooms in the spring. Bees are the primary pollinators, carrying pollen from the male hollies 1.5 to 2 miles, so it is not necessary to have a male plant in the same landscape.

Several male hollies are grown for their compact formal shape and interesting new foliage color. Dwarf Yaupon Hollies (Ilex vomitoria ‘Shillings’ and ‘Bordeaux’) form symmetrical spheres without extensive pruning. ‘Bordeaux’ Yaupon has maroon-colored new growth. Neither cultivar has berries.

Hollies prefer to grow in partial shade but will do well in full sun if provided adequate irrigation. Most species prefer well-drained, slightly acidic soils. However, Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) and Gallberry (Ilex glabra) naturally occurs in wetland areas and can be planted on wetter sites.

Evergreen trees retain leaves throughout the year and provide wind protection. The choice of one type of holly or another will largely depend on prevailing environmental conditions and windbreak purposes. If, for example, winds associated with storms or natural climatic variability occur in winter, then a larger leaved plant might be required.

The natives are likely to be better adapted to local climate, soil, pest and disease conditions and over a broader range of conditions. Nevertheless, non-natives may be desirable for many attributes such as height, growth rate and texture but should not reproduce and spread beyond the area planted or they may become problematic because of invasiveness.

There is increasing awareness of invasiveness, i.e., the potential for an introduced species to establish itself or become “naturalized” in an ecological community and even become a dominant plant that replaces native species. Tree and shrub species can become invasive if they aggressively proliferate beyond the windbreak. At first glance, Brazilian pepper (Schinus terebinthifolius), a fast-growing, non-native shrub that has a dense crown, might be considered an appropriate red berry producing species. However, it readily spreads seed disbursed by birds and has invaded many natural ecosystems. Therefore, the Florida Department of Environmental Protection has declared it illegal to plant this tree in Florida without a special permit. Consult the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s Web page (www.fleppc.org) for a list of prohibited species in Florida.

For a more comprehensive list of holly varieties and their individual growth habits refer to ENH42 Hollies at a Glance: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg021

by Sheila Dunning | Nov 3, 2017

Since we are approaching the peak dates in mid-October, it is time to get your gardens ready for migrating monarchs to fuel up on nectar sources. In their Mexican overwintering sites, these monarchs will have to survive on stored fat all winter. So they need to build up fat reserves by feeding on flowering plants along their migration route. Saltbush, Goldenrod, Narrowleaf Sunflower, Blanketflower and Milkweed are some of the nectar-rich blooms in the Florida Panhandle this time of year.

Since we are approaching the peak dates in mid-October, it is time to get your gardens ready for migrating monarchs to fuel up on nectar sources. In their Mexican overwintering sites, these monarchs will have to survive on stored fat all winter. So they need to build up fat reserves by feeding on flowering plants along their migration route. Saltbush, Goldenrod, Narrowleaf Sunflower, Blanketflower and Milkweed are some of the nectar-rich blooms in the Florida Panhandle this time of year.

Monarchs begin leaving the northern US and Canada in mid-August. They usually fly for 4-6 hours during the day, coming down from the skies to feed in the afternoon and then find roosting sites for the night. Warmth and nectar enable butterflies to gain the energy needed to keep on flying. Monarchs cannot fly unless their flight muscles reach 55ºF. On a sunny day, they bask by extending their wings to allow the black scales on their bodies to absorb heat. But on a cloudy day, they generally don’t fly if it is below 60ºF.

These graceful insects capitalize on the warm air they encounter when they head south. Thermals are columns of rising air, caused by uneven heating of the earth. They form wherever the air is just a few degrees warmer than the air next to it. Thermals often form wherever large patches of dark ground are adjacent to lighter-colored ground, such as over parking lots, above farm fields, highways, and next to rivers and lakes. Monarchs are so light that they can easily be lifted by the rising air.

But they are not weightless. In order to stay in the air, they must move forward while also staying within the thermal. They do this by moving in a circle. At that point, the monarch glides forward in a south/southwesterly direction with the aid of the wind. It glides until it finds another thermal, and rides that column of rising air upwards again. Monarchs can glide forward 3-4 feet for every foot they drop in altitude. If they have favorable tail winds, monarchs can flap their wings once every 20-30 feet and still maintain altitude.

When winds are from the south, monarchs fly very low, often choosing to land and find cover or refuel on available nectar sources. They may wait for the winds to change direction, and as a result, can form large roosts as they accumulate in a protected location.

The average pace of the migration is around 20-30 miles per day. But tag recoveries have shown that monarchs can fly 150 miles or more in a single day if conditions are favorable. Monarchs migrate during the day, coming down at night to gather together in clusters in a protected area. In the south, they might choose oak or pecan trees, especially if the trees are overhanging a stream channel.

Monarchs migrate alone—they do not travel in flocks like birds do. So they often descend from the sky in the afternoon to feed, and then search for an appropriate roosting site. Most roosts last only 1 or 2 nights, but some may last a few weeks.

How do monarchs find their way to Mexico? We really don’t know for certain. We do know that monarchs have a sun compass in their brain, and a circadian clock in their antennae. The clock and compass are integrated in the brain to form a time-compensated sun compass. Using the sun and polarized light waves, monarchs can maintain a general S/SW heading throughout the day. Even with that, it is amazing that they can find the exact spot year after year.

by Sheila Dunning | Mar 1, 2017

Swamp Redbay Tree infected with Laurel Wilt. Photo credit: Sheila Dunning

Many invasive plants and insects are introduced in packing materials, including 12 species of ambrosia beetles, which embed themselves in wood used as crates and pallets. While these tiny beetles don’t actually feed on wood, the adults and larvae feed on fungi that is inoculated into galleries within the sapwood by the females when they deposited their eggs. While the ambrosia fungus keeps the beetles alive, it kills the host tree. This is the projected fate of redbay trees (Persea borbonia) due to the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle.

First detected in the United States in a Georgia trap in 2002, Xyleborus glabratus, the Redbay Ambrosia Beetle, caused substantial mortality of redbay in northern Duval County, Florida in 2005. This ambrosia beetle introduces fungal spores, (Raffaelea lauricola) from specialized structures found at the base of their mandibles into the vascular system of plants when boring into host trees of the Lauraceae family. This insect and disease complex has collectively been named “Laurel Wilt.” Infected redbays, assafrass and avocado trees wilt and die within a few weeks or months.

Ambrosia Beetle life stages

The Redbay Ambrosia Beetle is a shiny black, cylindrical insect about 2 mm in length. The males are flightless and the females can only fly short distances (1 – 1.5 miles). Therefore, host trees are often attacked many times and stands of redbays are damaged quickly. Small strings of compacted sawdust may protrude from the bark at the point of initial attack. However, wind and rain easily remove this sign leaving the only symptom to be the total browning of foliage in a section of the tree’s crown. Since the fungus blocks the xylem (water-carrying) tissue of the redbay, it appears to wilt while leaves remain attached. Once infected, the trees cannot be saved.

To avoid spreading the beetle and pathogen to new areas, the trees need to be cut down and wood or chips from the infested trees should not be transported off site. Where allowed, the materials should be burned on site. Protection of unaffected trees is possible with expensive pesticides if applied in a timely manner and using the correct techniques. Removal of all susceptible tree species is not recommended. The survivors may hold a genetic tolerance.

by Sheila Dunning | Feb 28, 2017

Cuban Anole. Photo credit: Dr. Steve A. Johnson, University of Florida

The brown anole, a lizard native to Cuba and the Bahamas, first appeared in the Florida Keys in 1887. Since then it has moved northward becoming established in nearly every county in Florida. By hitching a ride on boats and cars, as well as, hanging out in landscape plants being shipped throughout the state, the Cuban anole (Anole sagrei) has become one of the most abundant reptiles in Florida. However, the native Carolina green anole (Anole carolinensis) has been impacted.

While both anole species are capable of thriving on the ground or in the trees, the invasive brown anole has altered the behavior of the native green anole by forcing them to remain arboreal. Anoles eat a wide variety of insects, spiders and other invertebrates. Cuban brown anoles feed on juvenile green anoles and their eggs, reducing their population even more. Brown anoles are brown to grayish in color. While they can adjust to various shades of light or dark, brown anoles cannot turn green. The native Carolina anole can camouflage itself by altering its skin color from light green to dark brown, including many hues in-between, but have no distinctive markings on their backs. Male brown anoles often have bands of yellowish spots, whereas females and juveniles have a light vertebral stripe with dark, scalloped edges. An additional identification feature is the dewlap of the male Cuban anole. Male anoles extend the skin of their lower jaw (the dewlap), displaying a bright orange to red color, in order to attract females or warn other males. Cuban brown anoles have a white line down the middle of the dewlap.

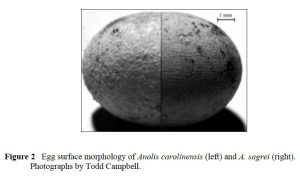

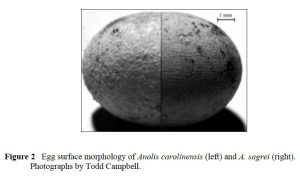

Egg surface of Native anole (left) vs Cuban anole (right). Photo credit: Todd Campbell

If the Cuban brown anole and Carolina green anole are placed side by side, the one with the shorter snout is the brown anole. Throughout the warm months, female anoles lay single, round eggs in moist soil or rotten wood at roughly 14 day intervals. The eggs of brown anoles have longitudinal grooves, whereas green anoles have raised bumps. Once identified, control measures can be taken. Brown anole eggs can be destroyed by freezing or boiling. Adult brown anoles can be located and captured by performing night time hunts with lights. Being diurnal, cold blooded creatures, Cuban anoles tend to congregate together under shrubs and along structures. Once collected the invasive Cuban brown anoles can be humanly euthanized by rubbing lidocaine on their skin and placing them in the freezer.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 20, 2017

4H youth assist an IFAS Extension agent in planting a tree. July 2008 IFAS Extension Calendar Photo. 4H children planting a small tree. 4H Club, youth groups, planting. UF/IFAS Photo: Josh Wickham.

Florida has celebrated Arbor Day since 1886 and has one of the first Arbor Day celebrations in the nation, on the third Friday in January. Trees establish a root system quickly when they aren’t expending as much energy on leaf development. So in Florida that is in the winter months; hence the reason for a January date for Arbor Day. However, installation anytime between October and March are suitable for most tree species. Palms are the exception. They require warm soil in order to root, so it best to plant them from April to August.

Planting and establishing trees is all about managing air and water in the soil. Three of the most common causes of poor plant establishment or even death include installing too deeply, under watering, and over watering. By selecting the appropriate species for the site, planting it at the correct depth, and irrigating properly trees should establish successfully. As simple as that sounds, many trees fail before they ever mature in the landscape.

Here are the ten steps to proper tree planting:

- Look up for wires and lights when choosing a site. Make sure that the location is more than 15 feet from a structure. Call 811 for underground utilities spotting at no cost.

- Remove any synthetic or metal materials from the top of the root ball.

- Find the topmost root (where the trunk meets the roots) and remove root defects, such as encircling roots. Loosed the root ball.

- Dig a shallow container-sized hole.

- Carefully place the tree in the hole. Don’t damage the trunk or break branches.

- Position the topmost root 1-2 inches above the soil grade.

- Straighten the tree. Be sure to check from two directions.

- Widen the hole to add backfill soil.

- Water to check for air pockets and hydrate the root ball. Add 3-4 inch thick layer of mulch at the edge of the root ball, with little to no mulch on top of the root ball.

- Prune for structural strength and damage removal. Stake if necessary in windy areas or if required by code.

These are probably not the steps used by previous generations. Twenty years of research has improved the techniques required for tree survival. Every year more and more trees are removed from storm damage, pest infestations, and development. Winter is time to add them back to both the urban and rural environments. Celebrate Arbor Day. Plant a tree. But, install it properly. Give your grandchildren the opportunity to enjoy it well into their adulthood.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.