by Rick O'Connor | Jan 12, 2026

Breeding is a major part of all animal life cycles, and this is no different for rattlesnakes. Like other reptiles there are separate sexes, and internal fertilization is the rule. For this to happen, during breeding season males must find the females and often must compete with other males for the right to breed.

Diamondback rattlesnake near condominium construction site Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Sawyer Asmar

Breeding typically occurs in the spring shortly after emerging from hibernation. The females are hungry from hibernating, but they must gain fat to help feed the developing young. In reptiles’ embryonic development usually occurs within an egg. Within this egg the developing embryo is connected to a yolk sac from which they feed. There is another attached sac called the allantois which is where they go to the bathroom. When the yolk sac is gone and the allantois is full, it is time to hatch. It is the mother’s job to produce this egg and place it somewhere where it will remain warm and protected. But here the rattlesnakes are a bit different.

They differ in that though they produce eggs, they do not lay them in a nest. Rather she keeps the eggs within her body for warmth and protection. The covering of their eggs is more of a membrane rather than a shell. During this gestation period, the females will find a hiding place where she can still access sunlight. She will position herself so that her body remains warm for her offspring and then lie for 2-3 months until they are born. Though she may drink, she usually does not eat during the period.

The mother typically produces about dozen such eggs and they emerge in early fall. The young are venomous and innately understand how to survive. However, the mother often stays with them until they shed their first skin, at which time she will leave them on their own. She will then binge feed preparing for the upcoming hibernation period.

Some females will breed again in the fall. These will store the sperm during hibernation and fertilize their eggs in the spring. During both the spring and fall breeding periods the males will venture far and wide to find females. It is during these periods when many come into contact with people in strange places. The drive to find females will have them move into neighborhoods and human habitats that they would otherwise avoid.

Rattlesnakes live around 25 years. They become sexually mature in 6-7 years but do not breed every year. It has been estimated that only one of the 12 or so newborns will make it to the age of three. With the infrequent breeding of adults and low success rate of the offspring, rattlesnakes are susceptible to population declines when adults are removed. The loss of habitat, road kills, decline in prey, natural predation, and indiscriminate killing by human’s rattlesnake populations can suffer, and many are considered species of concern.

Next, we will look at predator/prey interactions with rattlesnakes.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 29, 2025

All animals have a thermal range within which they can survive. For some it is very small range, for others it is amazingly large. Whatever their range is, they function best near the upper portion of it. “Warm blooded” animals (endotherms) have high metabolisms and generate warmth internally. Most have covering over their skin, fur or feathers, that assist with insulating them. “Cold blooded” animals (ectotherms) are the opposite. They have lower metabolisms, generate less internal heat, and most have covering over their skin (scales) that do not provide sufficient insulation. Thus, ectotherms must bask in the sun to get their body temperatures up to peak functioning levels. They will also hide in the shade or water to cool down. Rattlesnakes are ectotherms.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake crawling near Ft. Pickens Campground.

Photo: Shelley Johnson

Generally, the coldest part of the day is just before dawn. If a snake was hunting at night, and many species do, they will venture out in the morning to find a sunny spot to warm up so they can complete the digestive process. They do need sun, but they need to avoid open spaces where predators can find them. Often, they will select spots near the edge of a wooded area, or edge of rocky outcrop, so they can dash in if trouble arrives. Snakes have been known to stretch out on roads where the pavement has been heated during the day. Unfortunately, many are hit by vehicles while doing this. As the day warms up, they will move into cooler spaces to avoid overheating. Rattlesnakes are more active, and prefer to hunt during the daylight hours, though evening movements do occur.

There are seasonal behavior changes to deal with thermoregulation. During winter, in regions where it gets cold (maybe even snows), rattlesnakes will hibernate. Hibernation involves gorging on food in the fall to store fat to feed off during the hibernation period. Next, they will find a good hiding spot – a rocky den, a cave, gopher tortoise burrow, hole beneath a tree stump – where they will be safe from predation until spring. Once in this hibernaculum, they will lower their breathing and heart rate and allow their body temperature to drop. They go into a state of torpor where they are basically shut down. Many rattlesnakes use the same hibernacula each year, finding it by their sense of smell. Some species will share this space with several others – literally a den of snakes.

In the spring, when the air temperatures reach 70°F, they will emerge and immediately seek food. In some locations the summers will become very hot and so feeding and reproduction are on their minds before it becomes too hot, and they have to hide again. It is during these feeding/mating forays that many people encounter them. During this period they may move during periods of the day, and into locations they might avoid otherwise.

If they live in locations where summer can be very hot, they will repeat this behavior to avoid overheating – this is called aestivation. Another problem with hot summers is dehydration. Aestivation is more spontaneous than hibernation.

The eastern diamondback rattlesnake, the one often found on our barrier islands, lives only in the warmer parts of the southeastern U.S. It does get cold in some parts of their range, but they are not common where it snows. However, it does get very hot where they live and so even though hibernation is part of their life cycle, aestivation is common.

Next, we will look at reproduction.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 22, 2025

Though encounters with Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnakes are rare, bites from them are even more rare, and deaths from those bites almost nonexistent, it is worth discussing the issues and remedies of a bite.

The eastern diamondback rattlesnake is a classic serpent found in xeric habitats like barrier islands and deserts. They can be found in all habitats on barrier islands.

Photo: Bob Pitts

About 8000 people are bitten by snakes each year in the U.S. and Canada. Most are on the hands of men who were engaging the snake. 95% of those bitten are trying to either catch or kill them. Annually less than 12 people die from some species of rattlesnake bite. Many are young or old, with a suppressed immune system or pre-existing medical condition. Many who die, for whatever reason, refused medical treatment.

Most lethal bites are those that reach the heart or brain. However most bites are on the extremities where tissue and nerve damage can occur, but death is less likely. One reason some may refuse medical treatment is cost. Antivenin treatments are expensive. Typical bites may require 4-6 vials and costs were between $1500-$3500/vial in 2010. Add to this the cost of hospital stays, and you can see how expensive it can be.

Another reason given as to why medical attention was not sought is the fact that many venomous snakes will give what is called a “dry bite”. As mentioned in earlier articles, snake venom is “expensive” for snakes to produce, and it is intended for prey – not predators. Rattlesnakes will often give what is called a “bluff bite” – striking with their head but not even opening their mouths. The injection of venom is a voluntary action by the snake, and they may choose to inject very little, if any, venom even if the fangs penetrate. It is believed that about 50% of the rattlesnakes are dry bites. That said, you should never gamble on whether you received venom or not, you should go to the hospital.

The venom itself is a cocktail of proteins, polypeptides, digestive enzymes, and other compounds. It is basically modified salvia – which already includes some digestive enzymes. Myotoxins are a large component of rattlesnake venom. Myotoxins attack muscle tissue, cause pain, discoloration, minor bleeding, and swelling. This can be accompanied by chills, sweats, dizziness, disorientation, tingling and numbness of mouth and tongue, metallic taste, vomiting, diarrhea, bloody stools, alternating blood pressure and heart rates, blurred vision, muscle spasms, and neurotoxins can paralyze diaphragm leading to asphyxiation.

To avoid envenomation problems wear closed-toed shoes when hiking in rattlesnake territory. Do not extend your hand into brushy/grassy areas – use your hiking stick instead. Watch stepping over, or sitting on, logs and stumps without close surveying. Do not touch dead rattlesnakes, if not dead long, they can still bite. Carry a cell phone.

What to do if bitten…

Call 911.

Call poison control if you have their number.

Get to a hospital.

Remove rings, watches, etc. – swelling will occur.

Keep bite at, or below, heart level.

Remain calm.

What NOT to do if bitten…

Do not cut the wound.

Do not suck venom out.

Do not apply a tourniquet.

Do not apply ice.

Do not drink alcohol.

Do not use electroshock treatment.

Envenomation from an eastern diamondback rattlesnake is a scary thing. However, there are many ways to avoid this problem, and there is basic treatment if you are. Remember few people are bitten, and very few die. Get medical attention as soon as you can.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 15, 2025

It is understood that rattlesnakes are carnivores and will select some form of meat for their food. The general principle is to select something that is easy to kill and requires less energy to do so. Most rattlesnakes will select rodents but depending on the species and the part of the world they are in, some will select lizards or other prey.

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake.

Photo: Bob Pitts.

Due to their long periods of hibernation and/or aestivation, their feeding seasons are shortened. If you add low prey availability when they emerge from hiding, the feeding season is shorter still. They respond by binge eating – basically gorging on prey as often as they can. They may consume massive meals that will take over a week to digest.

Rattlesnakes who feed on rodents over lizards will grow larger. Many species have young with bright pink or yellow tips on their tails, much like cottonmouths and copperheads. These are used to lure small prey such as lizards and toads. They are predominantly ambush hunters, lying in wait for selected prey to wander into striking range. They like spots where they are half in the shade, half in the sun to do this.

Here is a scenario…

In the spring, when the temperature reaches 70°F, rattlesnakes will leave the hibernacula they used for hibernation. Having not eaten in a while, food is on their mind. They will use their sense of smell to find the trails of their potential prey, find a good ambush spot, and wait. Some studies suggest they sleep while waiting. They may first detect their prey by seeing it. It could be by hearing or smelling. Or by a combination of these. They will begin to flick their tongues – using the Jacobsen’s organ – to further identify the target. When within range, the facial pits can help “see” the target and assist in accuracy of their strike.

The strike is extremely fast. The snake injects their venom, releases, re-coils, and folds their fangs back into their sheath. The target often will run but is usually dead within a minute and not far away. The rattlesnake will now find the scent trail with their tongue and follow its meal. It can take several minutes to an hour to find it. Once found the prey is dead and already in the process of digestion due to some of the enzymes within their venom. In some prey the rattlesnake may not release and rather hold on to the prey after the bite. This often happens when they select birds, possibly due to the difficulty of finding them because they may fly before they die. Another interesting twist to this scenario holds for the timber rattlesnakes, who sometimes lie at the base of a tree with their heads facing up the trunk waiting on an unaware squirrel coming down.

Swallowing the prey involves “unhinging” their lower jaw making the diameter of their mouths larger. This way rattlesnakes can swallow large prey such as squirrels and rabbits. They have six rows of smaller pointed teeth in their mouths. There are two rows on the lower jaw, two on the upper, and two on the roof of their mouths. With the fangs folded back in their sheath, they begin to grab the prey with one set of jaws (the right or left) pull in, then alternate with the other jaw. It appears they are “walking the prey down” their throat. There is a tube called the glottis on the forward portion of the lower mouth that is used for breathing while their mouth is full. They have been seen taking breaks and resting while this process is ongoing. After swallowing, they re-align their lower jaw and find a place to rest and digest the meal.

Being ectothermic they will need to find warmth to digest their meal. They require internal temperatures between 80-85°F for proper digestion, so, they will need to find a location where there is good sunlight but enough cover to hide them. Depending on the size of the meal, digestion can last up to a week.

This scenario can be altered if prey density is low. If it is, rattlesnakes may move, and forage more than they typically do. As you can see, an approaching human during any part of this scenario would be unwanted by the snake.

In the next article we will take a closer look at the venom of these snakes.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 8, 2025

We will begin with a statement most know, but bears repeating… Snakes are just another animal trying to get through the day. They need to eat, avoid being eaten, find a place to sleep, and – at some point in the year – find a mate. They are no different than raccoons or hawks. But our reactions to these animals are very different to our reaction to raccoons and hawks. When hiking in the woods when someone says “bald eagle” the reaction is uplifting, maybe get a photo. But if someone says “snake” the reaction is different. If they say “rattlesnake” that reaction increases several magnitudes. In Manny Rubio’s book on rattlesnakes, he mentions that 50% of our population is “uneasy” about them and 20% are terrified of them – ophidiophobia is a real thing. That said, rattlesnakes are part of the barrier island ecology, and it is good to learn more about them.

This eastern diamondback rattlesnake was seen crossing a dirt road near DeFuniak Springs shortly after the humidity dropped.

Photo: Lauren McNally

Rattlesnakes are only found in the new world. There are 30 species listed in the U.S. and Canada and three of those live in Florida. One of them, the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, lives on our barrier islands. The pygmy rattlesnake may as well, but I have not encountered it (nor have heard of others encountering). The canebrake/timber rattlesnake is not common in Florida, and I have never heard of them on our islands.

These snakes differ from others in that they possess modified scales at the tip of their blunt tails we call rattles. Many snakes vibrate their tails when alarmed but this snake’s vibrations can be heard at a distance (up to 20-30 feet sometimes) to warn potential predators they are there. Each time the snake sheds its skin it will leave a new segment on the rattle. This is not a good way to age the snake however because they may shed several times in one year and older segments can break off. There have been reports of rattlesnakes with deformed tails and no rattles at all, but this is rare.

They also possess facial pits that have cells which can detect temperature radiating from an object, including “warm blooded” prey, while hiding. These thermal receptors lie along the bottom of the facial pit and are connected to the optic nerve; thus, they can sort of “see” heat.

Their eyesight is not as good as birds and mammals, and they have an elliptical pupil. They appear to use their eyesight in determining the size of the approaching animal and thus, their reaction to it.

They have nostrils but smell does not seem to play as important a role as Jacobsen’s organ does. This organ is found on the roof of their mouths. Rattlesnakes (all snakes) will flick their forked tongues to collect air molecules and stick the tip of each fork into a groove in the roof of their mouths that lead to this organ. Here they can taste/smell what is within their environment. The “taste” of potential prey will increase the frequency of tongue flicks and could cause the snake to move forward.

The fangs are the part of this animal we are most concerned about. They are hollow tubes connected to a venom gland which are located behind each jaw and give the snake the triangular head shape they are known for. These fangs are folded in a sheath so that they can close their mouths. Whether only one or both fangs are extended during a bite is controlled by the snake. Fangs often break off but smaller new ones are ready to replace them when needed. They will replace these fangs every two months, one at a time.

The strike involves opening the mouth, extending the fangs 90°, opening the mouth 180°, thrusting forward, bite down, inject, recoil, re-fold fangs, and back into the attack position. There are “offensive” and “defensive” strikes. Venom is “expensive” for snakes to produce and is meant for killing prey. The amount injected (if any at all) is controlled by the snake. A “defense” strike is slightly elevated. The upward angle reduces thrust and penetration depth.

Other general characteristics of rattlesnakes includes a triangular shaped head, most have a dark “mask” over their eyes, scales protruding over the eyes, keeled scales giving them a dry/rough appearance, and the males have longer tails than the females.

In our next post we will look at rattlesnake predation.

References

Rubio, M. 2010. Rattlesnakes of the United States and Canada. ECO Herpetological Publishing & Distribution. Rodeo, New Mexico. pp. 307.

Gibbons, W., Dorcas, M. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. The University of Georgia Press. Athens, Georgia. pp. 253.

Graham, S.P. 2018. American Snakes. John’s Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, Maryland. pp. 293.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 7, 2025

This tree was downed during Hurricane Michael, which made a late-season (October) landfall as a Category 5 hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

There are plenty of jokes about the four seasons in Florida—in place of spring, summer, fall, and winter; we have tourist, mosquito, hurricane, and football seasons. The weather and change in seasons are definitely different in a mostly-subtropical state, although we in north Florida do get our share of cold weather (remember that snow this year?!).

A disaster supply kit contains everything your family might need to survive without power and water for several days. Photo credit: Weather Underground

All jokes aside, hurricane season is a real issue in our state. With the official season having recently begun (June 1) and running through November 30, hurricanes in the Gulf-Atlantic region are a legitimate concern for fully half the calendar year. According to records kept since the 1850’s, Florida has been hit with more than 120 hurricanes, double that of the closest high-frequency target, Texas. Hurricanes can affect areas more than 50 miles inland, meaning there is essentially no place to hide in our long, skinny, peninsular state.

Flooding and storm surge are the most dangerous aspects of a hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I point all these things out not to cause anxiety, but to remind readers (and especially new Florida residents) that is it imperative to be prepared for hurricane season. Just like picking up pens, notebooks, and new clothes at the start of the school year, it’s important to prepare for hurricane season by firing up (or purchasing) a generator, creating a disaster kit, and making an evacuation plan. We even have disaster preparedness sales tax exempt holidays in Florida; one in early June and another in the heart of the season, August 24-September 6.

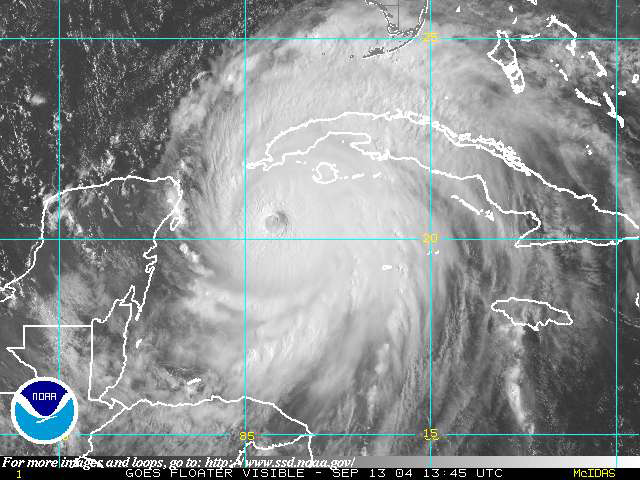

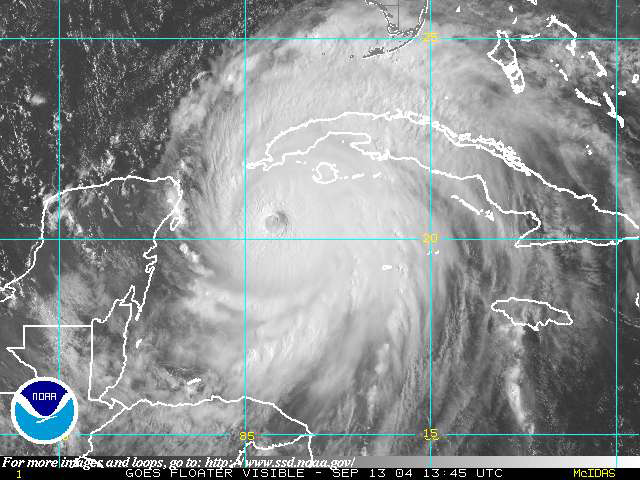

Peak season for hurricanes is September. Particularly for those in the far western Panhandle, September 16 seems to be our target—Hurricane Ivan hit us on that date in 2004, and Sally made landfall exactly 16 years later, in 2020. But if the season starts in June, why is September so intense? By late August, the Gulf and Atlantic waters have been absorbing summer temperatures for 3 months. The water is as warm as it will be all year–in 2023 even reaching over 100 degrees Fahrenheit–as ambient air temperatures hit their peak. This warm water is hurricane fuel—it is a source of heat energy that generates power for the storm. Tropical storms will form early and late in the season, but the highest frequency (and often the strongest ones) are mid-August through late September.

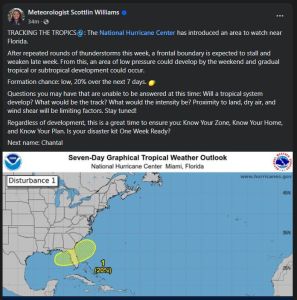

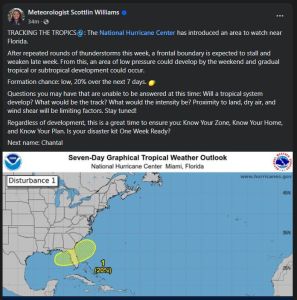

Pay attention to local meteorologists on social media, news, and radio. This alert was posted just yesterday online by the Escambia County Emergency Management Coordinator.

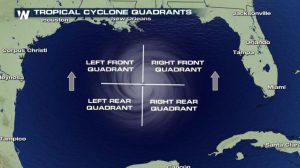

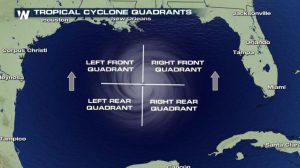

If you have lived in a hurricane-prone area, you know you don’t want to be on the front right side of the storm. For example, here in Pensacola, if a storm lands in western Mobile or Gulf Shores, Alabama, the impact will nail us. Meteorologists divide hurricanes up into quadrants around the center eye. Because hurricanes spin counterclockwise but move forward, the right front quadrant will take the biggest hit from the storm. A community 20 miles away but on the opposite side of a hurricane may experience little to no damage.

The front right quadrant of a hurricane is the strongest portion of a storm. Photo credit: Weather Nation

Hurricanes bring with them high winds, heavy rains, and storm surge. Of all those concerns, storm surge is the deadliest, accounting for about half the deaths associated with hurricanes in the past 50 years. Many waterfront residents are taken by surprise at the rapid increase in water level due to surge and wait until too late to evacuate. Storm surge is caused by the pressure of the incoming hurricane building up and pushing the surrounding water inland. Storm surge for Hurricane Katrina was 30 feet above normal sea level, causing devastating floods throughout coastal Louisiana and Mississippi. Due to the dangerous nature of storm surge, NOAA and the National Weather Service have begun announcing storm surge warnings along with hurricane and tornado warnings.

For helpful information on tropical storms and protecting your family and home, look online here for the updated Homeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for Natural Disasters, or reach out to your local Extension office for a hard copy.