by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2021

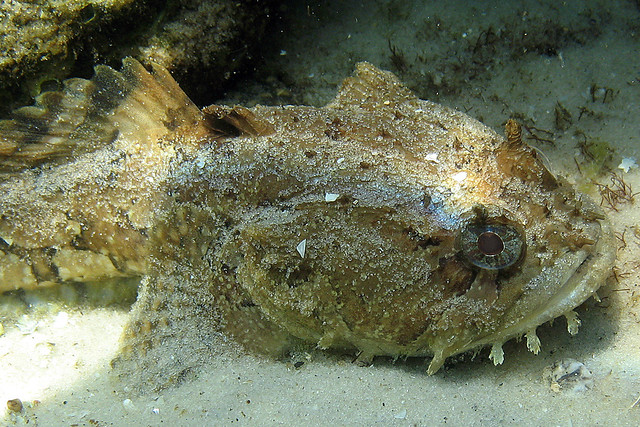

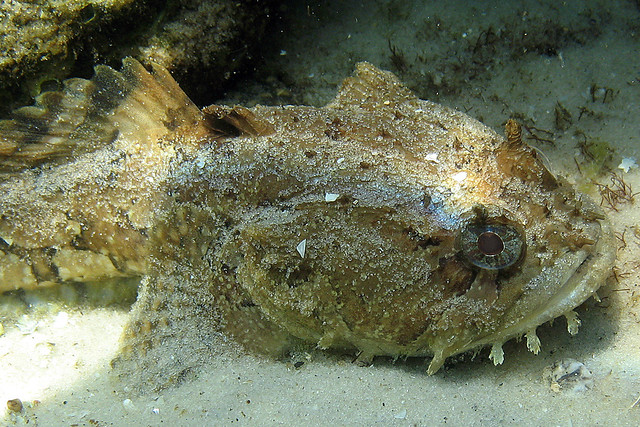

This is a group of fish that few have heard of and many have not seen – or if they saw them, had NO idea what they were – but they a very common in our local waters… the toadfish.

Once you see one, you will know why they call it this. Recently we had a matching game set up for the public to try and match the name of a common seagrass animal with its photograph. The toadfish was one of 20 species on the board. Few knew what it was and most only matched it with the photo through a process of elimination. A common response was “well… this MUST be the toadfish”, though there were just as many who did not see the connection between the name and the look on this fish’s face.

All that said, they are very common here. Snorkeling in our bays I have found them hiding in burrows within the grassbeds, snug against a seawall, and in open spaces within a rock jetty. They are known to hide inside discarded cans and bottles, feeding and eventually growing to large to be able to leave!

They are known for their painful bites; I have personally experienced this. We have captured them when seining the grassbeds. Trying to remove them from the net they are very slimy and difficult to grab. If you get close to their mouth, they will use the teeth they have. Others have been bitten when exploring the inside of a can or bottle left on the bottom. Toadfish belong to the family Batrachoididae and some members of this family are highly venomous. However, of the three species found in the northern Gulf, only the midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) possess venom, and it is not harmful to humans.

I guess in a word you could say these are ugly fish – hence their name. They are all benthic and remain on the bottom at all times. Most of the swimming they do is to a new hiding place, where they ambush their prey. There are three species found in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Midshipman

Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Atlantic Midshipman (Porichthys porosissimus) is a light tan colored fish with dark brown blotches along its side. Because of their light color, they are more common on light colored sand. The ones I have found are on the nearshore bottom of the Gulf side of our barrier island. They posses rows of photophores, cells that can produce light, and these rows of photophores resemble the rows of bright buttons on the 19th century midshipman’s naval uniform – hence their name. This fish has a mean length of eight inches. The midshipman has a more extensive range than the typical “Carolina” Gulf fish. They can be found from Virginia all the way to Argentina; beyond the Brazil limit most “Carolina” fish have. Though not reported on the other side of the Atlantic, nor the Pacific, this species seems to have few barriers impeding its dispersal.

The leopard toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The Leopard Toadfish (Opsanus pardus) is a larger toadfish reaching 12 inches. They too have a light-colored body with dark markings. It prefers reefs and rocky areas offshore. The only ones I have seen, or captured, were on our artificial reefs. It was noted early on in the lionfish invasion, that lionfish were not as numerous on reefs where leopard toadfish existed. This spawned a hypothesis that leopard toadfish may actually consume lionfish. A small study conducted at a local high school marine science program found that was not the case. I am not aware of any further studies on the relationship between these two, but it could be they just compete for space and the leopard toadfish wins some of these. Though not reported from Argentina, this species does have a large range – including the entire U.S. Atlantic seaboard, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and much of the Caribbean. Again, few barriers to their dispersal.

The common estuarine Gulf toadfish.

Photo: Flickr

The most frequently encountered toadfish is the Gulf Toadfish (Opsanus beta) – also know as the oyster dog, dogfish, or mudfish. This is the largest of the native toadfish at 15 inches. It is most common inside our estuaries living on oyster reefs, burrows in seagrass beds, jetties, and any sunken debris such as pipes, concrete, or pilings. Because of its habitat choice, this toadfish is much darker in color, having some light bars or markings on its side. This is the species that is sometimes found in sunken bottles and cans. This is a Gulf species found throughout the Gulf of Mexico, and some portions of the West Indies, but absent from most of the Caribbean and the Atlantic coast where it is replaced by its close cousin Opsanus tau. There does seem to be a barrier near the Florida straits that impedes its dispersal east and north of the Gulf. There are two species on each side suggesting a long period of isolation from each other and no interbreeding. Again, there is a barrier there.

I am not sure whether you have seen any of the local toadfish while snorkeling or diving. They are occasionally caught on rod and reel, but not often. However, now that you know about them, I am sure you will see one while out on the waters.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2021

Catfish…

There are a lot of fish found along the Florida panhandle that many are not aware of, but catfish are not one of them. Whether a saltwater angler who captures one of those slimy hardhead catfish to a lover of freshwater fried catfish – this is a creature most have encountered and are well aware of.

Growing up fishing along the Gulf of Mexico, the “catfish” was one of our nemesis. Slinging your cut-bait out on a line, if you were fishing near the bottom, you were likely to catch one of these. Reeling in a slimy barb-invested creature, they would swallow your bait well beyond the lip of their mouths and it would begin a long ordeal on how to de-hooked this bottom feeder that was too greasy to eat. Many surf fishermen would toss their bodies up on the beach with the idea that removing it would somehow reduce their population. Obviously, that plan did not work but ghost crabs will drag their carcasses over to their burrows where they would consume them and leave the head skull that gives this species of catfish it’s common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead” catfish. This hard skull has bones whose shape remind you of Jesus being crucified and was sold in novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”.

The bones in the skull of the hardhead catfish resemble the crucifixion of Christ and are sold as “crucifix fish”.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

When I attended college in southeast Alabama a group of friends wanted to go out for fried catfish. I, knowing the above about saltwater catfish, replied “why?… no…, you don’t eat catfish”. They assured me you did and so off we went to a local restaurant who sold them. Fried catfish quickly became one of my favorites. A fried catfish sandwich with slaw and beans is something I always look forward to. At that time, I was not aware of the freshwater catfish, nor the catfish farms that produce much of the fish for my sandwiches. I now have also become aware of the method of catching freshwater catfish called “noodling” – which is not something I plan to take up.

Worldwide, there are 36 families and about 3000 species of what are called catfish1. Most are bottom feeders with flatten heads to burrow through the substrate gulping their prey instead of biting it. Most possess “whiskers” – called barbels, which are appendages that can detect chemicals in the environment (smell or taste) helping them to detect prey that is buried or hard to find in murky waters. These barbels resemble whiskers and give them their common name “catfish”.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

They lack scales, giving them the slimy feel when removing them from your hook, and also have a reduced swim bladder causing them to sink in the water – thus they spend much of their time on the bottom. The mucous of their skin helps in absorbing dissolved oxygen through the skin allowing them to live in water where dissolved oxygen may be too low for other types of fish1.

They are also famous for their serrated spines. Usually found on the dorsal and pectoral fins, these spines can be quite painful if stepped on, or handled incorrectly. Some species can produce a venom introduced when these spines penetrate a potential predator which have put some folks in the hospital1.

The size range of catfish is large; from about five inches to almost six feet. In North America, the largest captured was a blue catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) at 130 pounds. The largest flathead catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) was 123 pounds. But the monster of this group is the Mekong catfish of southeast Asia weighing in at over 600 pounds.

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission lists six species of catfish in the Florida panhandle area. However, they are focusing on species that people like to catch2.

The Blue Catfish

Photo: University of Florida

This large blue catfish is being weighed by FWC researchers. Photo: Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission

The Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) is found throughout Florida and also in many river systems of the eastern United States. It has found few barriers dispersing through these river systems. They are not typically bottom feeders having a more carnivorous diet.

The Flathead Catfish (Pylodictis olivaris) are relatively new to Florida and are currently reported in the Escambia and Apalachicola rivers. They prefer these slow-moving alluvial rivers.

The Blue Catfish (Ictalurus furcatus) were first reported in the Escambia and Yellow Rivers, there are now records of them in the Apalachicola. These catfish prefer faster moving rivers with sand/gravel bottoms and seem to concentrate towards the lower ends of major tributaries.

The White Catfish (Amerius catus) is found in rivers and streams statewide, and even in some brackish systems.

The Yellow Bullhead (Amerius natalis) are most often found in slow moving heavily vegetated systems like ponds, lakes, and reservoirs. It is reported to be more tolerant of poor water conditions.

The Brown Bullhead (Amerius nebulosus) live in similar conditions to the Yellow Bullhead.

The dispersal of freshwater catfish is interesting. How do they get from the Escambia to the Apalachicola Rivers without swimming into the Gulf and up new rivers? The answer most probably comes from small tributaries further upstream that can, eventually, connect them to a new river system. Scientists know that eggs deposited on the bottom can be moved by birds who feed in each of the systems carrying the eggs with them as they do. And you cannot rule out movement by humans, whether intentionally or accidentally.

On the saltwater side of things, there are two species – though the blue catfish has been reported in the upper portions of some estuaries in low salinities in the western Gulf of Mexico. The marine species are the hardhead catfish (Arius felis), sometimes known as the “steelhead” or the “sea catfish” – and the gafftop (Bagre marinus), also known as the gafftopsail catfish3.

The hardhead catfish is very familiar with anglers along the Gulf coast. This is the one I was referring to at the beginning of this article. It is considered inedible and a nuisance by most. They are common in estuaries and the shallow portions of the open sea from Massachusetts to Mexico. They are reported to have an average length of two feet, though most I have captured are smaller. Like many catfish, they possess serrated spines on their dorsal and pectoral fins. Their distribution seems to be limited by salinity.

The gafftop is also reported to have a mean length of two feet, and most that I have captured are closer to that. At one point in time, we were longlining for juvenile sharks in Pensacola Bay and caught numerous of these thinking they were small bull sharks as we pulled the lines in, until we saw the long barbels extending from them. I remember this being a very slimy fish, covered with mucous, and not fun to take off the hooks. It is reported to have good food value, though I have not eaten one. They differ from the hardheads mainly in their extended rays from the dorsal and pectoral fins. The habitat and range are similar to hardheads, though they have been reported as far south as Panama.

The extended rays of the gafftop catfish.

Photo: University of Florida.

The diversity of freshwater catfish in the U.S. goes beyond what has been reported here. This group has been found on most continents and have been very successful. There are plenty of local catfish farms where you can try your luck, have them cleaned, and enjoy a good meal.

References

1 Catfish. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Catfish.

2 Catfish. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/fishing/freshwater/sites-forecasts/catfish/.

3 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 2, 2021

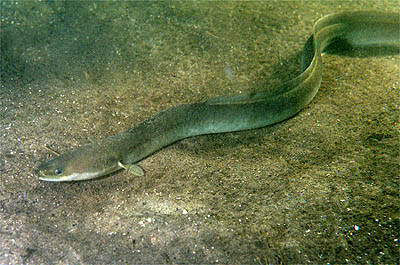

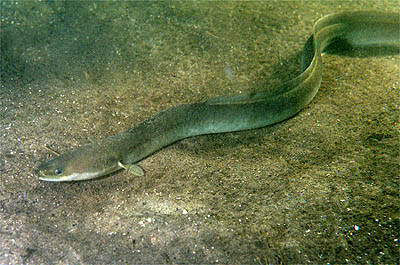

Eels… when that name comes up most think of either the vicious moray eels or the famous electric eel. Moray eels do exist in the Florida panhandle, and we will talk about them. Electric eels do not, they are found in the Amazon River system. That said, we do have eels here – quite a few. There are at least 18 species found in six different families. Most are 2-3 feet in length, though the Banded Shrimp Eel (Ophichthus) can reach six feet. About half of them are found offshore on the middle and outer shelves, the other half can be found in the inner shelf and estuaries, a few species swim into freshwater. Shrimpers often catch them when trawling and occasionally anglers will catch them with rod and reel.

Eels superficially resemble snakes and sometimes are confused with them. I have been told more than once that we do have sea snakes here. We do not. What people are finding are one of the 18 species of eels in the area. We do have snakes swimming across our estuaries, but we do not have sea snakes.

Eels differ from snakes primarily in that they, being fish, possess gills – not lungs. Most eels do have sharp teeth, the morays are famous for theirs, but no eels are venomous – so no worries there. Most of our eels have very small scales or are completely scaleless and are often very slimy and difficult to handle. They have been used as bait and one species, the American eel (Anguilla rostrata), has been used for food.

The Anguilla eel, also known as the “American” and “European” eel.

Photo: Wikipedia.

The American eel has an interesting life history. They spawn in the Sargasso Sea, an area in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. Their developing leptocephalus larva are thin, flat, and transparent in the water. They drift with the ocean currents into the Gulf of Mexico and eventually into our estuaries. I have found them along the shores of Project Greenshores (in Pensacola Bay) during certain parts of the year. From here they work their ways into our local rivers where people encounter the large adults. I have found them living in submerged caves near Marianna and many locals have found them at the bottom of our rivers. When time to breed, the adults will leave and head back to the open Atlantic to begin the cycle again. An amazing trip.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray eels are famous for the nasty attitudes and vicious bites. They are more tropical and associated with offshore reefs, though the ocellated moray (Gymnothorax ocellatus) is often caught in shrimp trawls. They live in the crevices of the reef ambushing prey. Some, like the green moray, can get quite large – over six feet. Like all eels, they have very powerful muscles and sharp teeth.

The shrimp eel is common on our inner and middle continental shelf.

Photo: NOAA

Conger eels are very common despite few people ever seeing them. There are six species and they frequent the middle continental shelf, so are rare in estuaries.

There are eight species of snake, or worm, eels. These are more common on the inner shelf and the coastal estuaries. Many prefer muddy bottoms where they bury tail first to ambush prey swimming by.

The majority of these marine eels have a large geographic distribution. Their larva can be carried great distances in the currents and their need for sandy or muddy bottoms can be met just about anywhere. They appear to have few barriers keeping them from colonizing much of the Gulf and surrounding waters. Most fall into the category we call “Carolina Fish”. Meaning their distribution occurs from the Carolinas, throughout the Gulf of Mexico, south to Brazil. There are a few species that can tolerate the lower salinities of the estuaries and one, the Anguilla eel, that can even venture into freshwater.

There are few species restricted to the tropical reefs, such as the morays. But morays are found on our smaller middle shelf and artificial reefs in the northern Gulf. Though found in parts of the Atlantic Ocean, Hoese and Moore1 reported one species of conger eel, Uroconger syringus, as only occurring near south Texas in the Gulf of Mexico. What barriers keep it from colonizing other Gulf habitats is unknown.

Eels are true fish that we rarely encounter. Encounters are usually startling but exciting at the same time. They are pretty amazing fish.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 27, 2021

For those who lived in the Pensacola Bay area 50 or so years ago, this question comes up from time to time. By scallop I am speaking of the bay scallop (Argopecten irradians), the one sought by so many scallopers then and now. This relatively small bivalve sits on beds of turtle grass, gazing with their ice blue eyes, filtering the water for plankton and avoiding numerous predators. They only live for a year, maybe two. They aggregate in relatively large groups and mass spawn. Releasing male gametes first, then female, fertilizing externally in the water column, to create the next generation.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

These are unique bivalves in that they can swim… sort of. When conditions are not good, or a predator is detected, they can use their single adductor muscle to open and close the shells creating a current of expelling water that “pushes” them along and off the bottom. They were once found from Pensacola to Miami… but no longer. Scallops have become almost nondetectable in much of their historic range. Today they congregate in the Big Bend area of the state, and there they are heavily harvested.

What happened?

Well, if you look at the variety of causes for species decline around the globe habitat loss is usually at the top of the list. The habitat of the bay scallop are seagrass beds. There are many publications reporting the loss of seagrasses across the Gulf and Atlantic coast. Locally we know that the historic beds of the Pensacola Bay system have declined. We also know that some of those beds have shown some recovery in the last 20 years. But was the loss enough to cause the decline of the scallop?

Studies show that there is a strong association between seagrasses and scallops. The planktonic larva typically attached to grass blades a week or two after fertilization. This seems essential to reduce predation. Once they drop from the blades, vegetative cover is important for their survival. This suggests yes – any loss of seagrass could begin the loss of bay scallops.

What about water quality?

We do know that scallops need more saline brackish water – at (or above) 20 parts per thousand (20‰); 10‰ or less is lethal. Sea Grant is currently working with citizen scientists in Escambia County to monitor the salinity of area waters weekly. Though we do not believe the data is usable until we have 100 readings from each location, early numbers suggest that locations in Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound are at 20‰ threshold. We do not know whether run-off engineering of the 1970s may have lowered the salinity to cause a die-off, and one would think (since they can swim) they would move to a better location. However, if salinities were low across much of their local range, and seagrasses were not available in areas where salinities were good, this could have a devasting impact on their numbers.

Then there is sedimentation. Studies show that young scallops (<20mm) that do not have seagrass to attach to settle on silty bottoms and their survival is very low. And then there are toxic metals, and other contaminants that scallops may have little tolerance for. It is known that juvenile scallops have a low tolerance for mercury.

Disease?

One study from the Tampa Bay area indicated that there was little loss of scallops due to disease and parasites.

And then there is overharvesting…

Scallops are mass spawners and there needs to be high numbers of adults near each other for reproduction to be successful. If people are taking too many, this can lead to more spaced adults and less chance of successful fertilization. This combined with environmental stressors probably did our populations in.

According to a publication from Sarasota Bay Estuary Program in 2010, populations of less than five scallops / 600m2 is considered collapsed. Sea Grant has been conducting volunteer scallop searches in the Pensacola Bay area for the last five years. In that time, we have found only one live scallop… we have collapsed. During the 2021 Scallop Search, 17 volunteers surveyed 4000m2 and found no live scallops. However, reports of live scallops outside of our surveys indicate they are still there. We will see what the future holds.

References

Castagna, Michael, Culture of the Bay Scallop, Argopecten irradians, in Virginia (1975). Marine Fisheries

Review, 37(1), 19-24.

https://scholarworks.wm.edu/vimsarticles/1200

Leverone, J.R. 1993. Environmental Requirements Assessment of the Bay Scallop

Argopecten Irradians Concentricus. Final Report. Tampa Bay Estuary Program. Pp.82.

Leverone, J.R., S.P. Geiger, S.P. Stephenson, and W.S. Arnold. 2010. Increase in Bay Scallop (Argopecten irradians) Populations Following Releases of Competent Larvae in Two West Florida Estuaries. Journal of Shellfish Research. Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 395-406.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 18, 2021

This is a famous fish. If you look back at the old tourism magazines of the early 20th century you will see a lot about tarpon fishing in Florida. As a matter of fact, some say that tarpon fishing was the beginning of the tourism industry in the state. Also known as “silver kings”, they put up a tremendous fight which anglers love, particularly on lighter tackle. It is a sport fish, not sought for food, so catch and release has been the rule for years. But those who seek them will tell you it is worth the fight even if you must release it.

Tarpon have been a popular fishing target for decades.

Photo: NOAA

Tarpon (Megalops atlantica) are large bodied, large scaled fish, with a deep blue back and silver sides. They are a large fish, reaching over 8 feet in length and up to 350 pounds. They tend to travel in schools and are often associated with other fish, such as snook2.

It has always been thought of as a “south Florida fish”. As mentioned, down there it is a popular fishing target for tourist and residents alike. Many charter captains specialize in catching the fish and they have been featured in fishing programs. But you do not hear about such things in the Florida panhandle. Hoese and Moore1, as well as the Florida Museum of Natural History2 both indicate that they are in fact in the Florida panhandle. As a matter of fact, this fish has few barriers and has the distribution of the classic “Carolina fish” group. That includes the entire eastern seaboard of the United States, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean1. The Florida Museum of Natural History indicates they are found on the opposite shores of the Atlantic Ocean and may have made their way through the Panama Canal to the Pacific shores of the canal. Within this range they are known to enter freshwater rivers. They seem to have few biogeographic barriers.

I grew up in the panhandle and remember hearing about them swimming in our area when I was younger. Fishermen said they would throw all sorts of bait at them. Artificial lures, live bait, cut bait, you name it – they tossed it… the tarpon never would take it. Catching one here was almost impossible. The flats fishing charter trips for tarpon in south Florida would not happen here. I remember once diving in Pensacola Bay near Ft. Pickens. We were looking for an old Volkswagen beetle that had been sunk years ago when at one point the water became very dark – almost like storm clouds had rolled in. When my buddy and I both looked up we saw a school of very large fish swimming above us. We were not sure what they were at first but as we slowly ascended, we realized they were tarpon. It was pretty amazing.

An interesting side note here. In 2020 tarpon were once again seen swimming around the Pensacola area but this time they WERE taking bait. There were several reports of tarpon caught off the Pensacola Fishing Pier and inside the bay. Why change over all this time? I am not sure.

The ladyfish (or skipjack) is the smaller cousin of the tarpon, but puts up a good fight as well.

Photo: University of Southern Mississippi

Tarpon belong to the family Elopidae which also includes another local fish known as the “ladyfish” or “skipjack” (Elops saurus). This is a much smaller fish reaching about 3 feet (and that would be a large ladyfish). The scales of this family member are much smaller, but the fight on hook and line is just as large. The characteristic that places these two fish into the same family (and these are the only two in this family) is the hard bony gular plate found between the right and left side of the lower jaw (in the “throat” area).

Like tarpon, it is not prized as a food fish but more of a game fish. It has the classic wide distribution of the “Carolina fish group” – the eastern seaboard of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, down to Brazil. Like the tarpon, it is found in brackish conditions but is not mentioned in freshwater. Again, few biogeographic barriers for this fish.

Both members of this family provide anglers young and old with a lot of enjoyment.

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Discover Fishes. Tarpon. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/megalops-atlanticus/.

3 Discover Fishes. Ladyfish. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/elops-saurus/.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 29, 2021

Sargassum washed ashore after a storm on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I am sure it drives the tourists a little crazy. After daydreaming all year of a week relaxing at the beach, they arrive and find the shores covered in leggy brown seaweed for long stretches. It floats in the shallow water, tickling legs and causing a mild panic—was that a fish? A jellyfish? A shark? Then, of course, high tide washes the seaweed up and strands it at the wrack line, shattering the vision of dreamy white sand beaches.

But for those visitors—and locals—willing to take a closer look, the brown algae known as sargassum is one of the most fascinating organisms in the sea. The next time you are at the beach, pick some up and turn it over in your hands. Sargassum is characterized by its bushy, highly branched stems with numerous leafy blades and berry-like, gas-filled structures. The tiny air sacs serve as flotation devices to keep the algae from sinking. This unique adaptation allows it to fulfill a niche at the top of the water column, instead of growing at the bottom or on another organism.

The sargassum fish blends incredibly well into its home within sargassum mats. It uses handlike pectoral fins to move around. Photo credit: Reef Builders

Sargassum tends to accumulate into large mats that drift through the water in response to wind and currents. These drifting mats create a pelagic habitat that attracts up to 70 species of marine animals. Several of these organisms are adapted specifically to life within the sargassum, reaching full growth at miniature sizes and camouflaged in shape, pattern, and color to blend in. These very specialized fauna include the sargassum crab, the sargassum shrimp, sargassum flatworm, sargassum nudibranch, sargassum anemone, and the sargassum fish! The sargassum fish (Histrio histrio) is in the toadfish family, a group of slow-moving reef fish that pick their way through coral and algae by using their pectoral fins like hands. Sea turtle hatchlings will spend their early years feeding and resting within the relative safety of large mid-ocean sargassum mats.

The small air-filled sacs of sargassum allow it to float on the surface, becoming the basis of a teeming ecosystem. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Over time the air sacs lose buoyancy and the sargassum sinks, providing an important source of food for bottom-dwelling creatures. If washed ashore, many of the animals abandon the sargassum or risk drying out and dying.

In general, most of the larger, familiar seaweeds like sargassum are brown algae. Brown algae (including kelp and rockweed) have colors ranging from brown to brownish yellow-green. These darker colors result from the brown pigment fucoxanthin, which masks the green color of chlorophyll. Extractions from brown algae are commonly used in lotions and even heartburn medication!