by Chris Verlinde | May 1, 2020

Black Skimmers foraging for fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmers and Least Terns, state listed species of seabirds, have returned along the coastal areas of the northern Gulf of Mexico! These colorful, dynamic birds are fun to watch, which can be done without disturbing the them.

Shorebirds foraging. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmer with a fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

What is the difference between a seabird and shorebird?

Among other behaviors, their foraging habits are the easiest way to distinguish between the two. The seabirds depend on the open water to forage on fish and small invertebrates. The shorebirds are the camouflaged birds that can found along the shore, using their specialized beaks to poke in the sandy areas to forage for invertebrates.

Both seabirds and shorebirds nest on our local beaches, spoil islands, and artificial habitats such as gravel rooftops. Many of these birds are listed as endangered or threatened species by state and federal agencies.

Juvenile Black Skimmer learning to forage. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult black skimmers are easily identified by their long, black and orange bills, black upper body and white underside. They are most active in the early morning and evening while feeding. You can watch them swoop and skim along the water at many locations along the Gulf Coast. Watch for their tell-tale skimming as they skim the surface of the water with their beaks open, foraging for small fish and invertebrates. The lower mandible (beak) is longer than the upper mandible, this adaptation allows these birds to be efficient at catching their prey.

Least Tern “dive bombing” a Black Skimmer that is too close to the Least Tern nest. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult breeding least terns are much smaller birds with a white underside and a grey-upper body. Their bill is yellow, they have a white forehead and a black stripe across their eyes. Just above the tail feathers, there are two dark primary feathers that appear to look like a black tip at the back end of the bird. Terns feed by diving down to the water to grab their prey. They also use this “dive-bombing” technique to ward off predators, pets and humans from their nests, eggs and chicks.

Least Tern with chicks. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Both Black Skimmers and Least Terns nest in colonies, which means they nest with many other birds. Black skimmers and Least Terns nest in sandy areas along the beach. They create a “scrape” in the sand. The birds lay their eggs in the shallow depression, the eggs blend into the beach sand and are very hard to see by humans and predators. In order to avoid disturbing the birds when they are sitting on their nests, known nesting areas are temporarily roped off by Audubon and/or Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) representatives. This is done to protect the birds while they are nesting, caring for the babies and as the babies begin to learn to fly and forage for themselves.

Threats to these beautiful acrobats include loss of habitat, which means less space for the birds to rest, nest and forage. Disturbances from human caused activities such as:

- walking through nesting grounds

- allowing pets to run off-leash in nesting areas

- feral cats and other predators

- litter

- driving on the beach

- fireworks and other loud noises

Audubon and FWC rope-off nesting areas to protect the birds, their eggs and chicks. These nesting areas have signage asking visitors to stay out of nesting zones, so the chicks have a better chance of surviving. When a bird is disturbed off their nest, there is increased vulnerability to predators, heat and the parents may not return to the nest.

Black Skimmer feeding a chick. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

To observe these birds, stay a safe distance away, zoom in with a telescope, phone, camera or binoculars, you may see a fluffy little chick! Let’s all work to give the birds some space.

Special thanks to Jan Trzepacz of Pelican Lane Arts for the use of these beautiful photos.

To learn about the Audubon Shorebird program on Navarre Beach, FL check out the Relax on Navarre Beach Facebook webinar presentation by Caroline Stahala, Audubon Western Florida Panhandle Shorebird Program Coordinator:

In some areas these birds nest close to the road. These areas have temporarily reduced speed limits, please drive the speed limit to avoid hitting a chick. If you are interested in receiving a “chick magnet” for your car,  to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 17, 2020

I’d like to be a jellyfish… cause jellyfish don’t pay rent…

They don’t walk and they don’t talk with some Euro-trash accent…

Their just simple protoplasm… clear as cellophane

They ride the winds of fortune… life without a brain

These lyrics from Jimmy Buffett’s song Mental Floss sort of sums it up doesn’t it. The easy-going lifestyle of the jellyfish.

Everyone who visits the Gulf coast knows about these guys, but few people… very few… like them. For most, the term jellyfish signals “pain”, “fear”, and “death”. The purple flag is flying, and no one wants to enter the water. Folks from the Midwest call local hotels and condos asking, “when are the jellyfish going to be there?” It’s understandable. Who wants to spend their week vacation on the Gulf inside a hotel because you can’t go swimming?

I found this along the shore last winter. These are cannonball jellyfish.

I would almost (…almost) rather be diving with a shark than hundreds of jellyfish. When you spot them, they are everywhere. Quietly swarming like ghosts. You push them off and they appear to move towards you – almost like smoke from a campfire, you can’t get away.

They are creepy things. But amazing too!

As Mr. Buffett’s points out, they are simple “protoplasm”. Their body is primarily a jelly-like substance called mesoglea – and most of that is water. If you place a dead jellyfish on your dock and come back that afternoon, you will probably find just a “stain” of where it was – there is almost nothing to them.

The “bell” of the jellyfish is mostly mesoglea. Some jellyfish have thick layers of this, others much thinner. Some have a small flap of skin along the margins of the bell called the velum which they can undulate and swim – but they are not strong swimmers. If the tide is going out, swim as they may… their heading out also.

The bell shaped body of a jellyfish with numerous tentacles.

Many species of jellyfish have interesting markings within the bell. One has a white-colored structure that forms a 4-leaf clover. Another has red triangles all connecting at the center of the bell. For many, these structures are the ones that produce the gametes. Jellyfish reproduce sexually but are hermaphroditic – meaning they produce female eggs and male sperm in the same animal. There is no physical contact between animals, they just release the gametes into the ocean when they are in thick swarms and wah-la… new jellyfish – many new jellyfish.

On the bottom of the bell is a single opening that leads to a single pouch. This opening is the mouth, and the pouch is called the gastrovascular cavity. Jellyfish are predators – carnivores. There are no teeth, and most do not seek their prey – their prey finds them. Hanging from their bell are the tools of the killing trade, the part of this animal we do not like… the tentacles. Some tentacles can extend for several feet beyond the bell, others you can hardly notice them – but this is where the killing happens.

Along the tentacles there are small capsules called cnidoblasts which contain small cells called nematocyst. These nematocyst contain a coiled dart which at the end contains a drop of venom. There is a trigger associated with this cell. The jellyfish does not fire it – instead, the prey bumps the trigger and the nematocyst “fires”. The drop of venom is injected, along with the hundreds of other nematocysts along the tentacle the fish just bumped. This venom paralyzes the prey, other tentacles coil around it firing more nematocysts, and the tentacles retract towards the mouth – bingo… lunch.

This box jellyfish was found near NAS Pensacola in November of 2015.

Photo: Brad Peterman

Of course, the same happens when people bump into them. For us it is painful and unpleasant – but we are not consumed. That said, some species are quite painful. Some will force people to the hospital, and some have even killed people. The Box Jellyfish is the most notorious of these deadly ones. Known for their habits in Australia, there are at least two species found in the Gulf. The ones found here are not common, and there are no reported deaths, but they do exist. The Four-Handed is the one more widespread here. It actually has eyes, can detect predators and prey and swim towards or away from them, and the male fertilizes the female internally – not your typical jellyfish.

The more familiar painful one is the Portuguese Man-of-War. This creature is more like a sponge in that it is not just one creature but a large “condo” of many. Some cells are specialized in feeding, these are found on their long tentacles. Others specialize in reproduction; these are found near the blue colored air bag. They produce this blueish colored air bag which is exposed above the surface. The wind pushes on the bag like a sail and this moves the creature across the environment in search of food. Hanging from the bag are long tentacles which are made up of individuals whose stomachs are all connected. So, when one group of cells makes contact and kills a prey – they consume it and the tissue is moved through the connecting stomachs to feed the whole colony. To feed a whole colony, you need a big fish – to kill a big fish, you need a strong toxin, and they have it. These are VERY painful and have put people in the hospital, some have died. Some say that the Portuguese man-of-war is not a “true” jellyfish. This is true in the sense that they belong to a different class of jellyfish. There are three classes, the Scyphozoans being what we call the “true” jellyfish – Portuguese man-of-wars are not scyphozoans, but rather hydrozoans.

The colonial Portuguese man-of-war.

Photo: NOAA

Another interesting thing about jellyfish, is that they are all not jellyfish-like. As we just mentioned, there are two other classes and one other phylum of jellyfish-like animals. Hydrozoans and anthozoans are not your typical jellyfish. Rather than being bell-shaped and drifting in the ocean looking for food, they are attached to the seafloor and look more like flowers. Their tentacles are usually smaller but do contain nematocysts. Their toxin can be strong, some do eat fish, but most have a weaker toxin and feed on very small creatures – some only eat plankton. These would include the hydra, sea anemones, and the corals. As mentioned above, this also would include the Portuguese man-of-war.

Comb jellies are those jellies that drift in the currents and have no tentacles. We commonly collect them and toss them at each other. When I was growing up, we referred to them as “football jellies” because of this. The reason they do not sting is not because they do not have tentacles (some species do) but rather they do not have nematocyst and cannot. Rather they have special cells called colloblast that produce a drop of sticky glue at the end which they use to capture prey. Not having toxins, they cannot kill large prey but rather feed on smaller creatures like plankton and each other – they are cannibals. For this reason, they are in a whole different phylum.

The nonvenmous comb jelly.

Photo: Bryan Fluech

The jellyfish of the Gulf are a nuisance at times but are actually amazing creatures.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 7, 2020

These are some of the more familiar Florida turtles we have. Working with youth, I often hear them called “snapping turtles” because (a) these are the most common turtles they encounter, and (b) snapping turtles are the only name they know 😊

I myself had a “pet” box turtle when I was young named… “snappy”. Yep…

This Gulf Coast box turtle has a lot of yellow on the shell. Their shell coloration varies.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

That said, they do seem to be very common everywhere. Neighborhoods, parks, gardens, farms, you name it, people find these things. However, research suggests that the “commonness” of these guys maybe just in encounters with the same individuals, we really do not know how common they are.

They are a great way to introduce youth to the world of turtles. When picked up they quickly withdraw and close their shells – the only turtles we have that can completely do this (watch out though, they do have a habit of urinating when held).

There is debate as to how many kinds of box turtles we have. Most agree that the four that have been listed are all subspecies of Terrapene carolina. This turtle is typically called the “Eastern” box turtle. This species does exist and is quite common along the Atlantic seaboard. If differs from other subspecies in that the back end of the carapace ends abruptly – there is no “flare” to the margins of the carapace.

The lined pattern of this carapace identifies it as the Florida box turtle.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

What they do agree on is that two subspecies – the Florida box turtle (T. carolina bauri) does live in Florida – in the peninsular part of the state; and the Gulf Coast box turtle (T. c. major) does as well – in the panhandle. The two that are questionable are the Eastern box turtle (T. c. carolina) and the Three-toed box turtle (T. c. triunguis). As said before the Eastern definitely exists north of us but not sure whether it is in Florida. The Three-toed lives west of us but, again, not sure in Florida.

The Florida box turtle has a dark carapace with straight lined yellow streaks (like a sunbeam burst) pattern across its shell. The back end of the shell ends abruptly as it does in the Eastern. The Gulf Coast box turtle is the big boy of the group. Most of these box turtles have carapace lengths no more than 7 inches long. The Gulf Coast can be as long as 8 inches and the back-end margin of the carapace is flared. The pattern of color on the Gulf Coast varies. It can be red, yellow, brown and the lighter colored markings can be varied as well.

Box turtles are emydid turtles – which are usually associated with freshwater – but box turtles are much more terrestrial than their cousins. Some even referred to them as tortoises, but they are not. They like a variety of habitats being found in dry scrub pine forests, damp wet palm hammocks, and occasionally in marshes. Their hind feet are slightly webbed, but they are not great swimmers and are rarely found in deep water. That said, they do love rain. When it rains, they are on the move looking for food and places to lay eggs.

The abrupt downward end of the carapace and blotched pattern of the shell identifies this as an Eastern box turtle.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Research suggests that each turtle will inhabit about 5 acres and that a single acre can support up to 16 animals. They are omnivorous and eat a variety of invertebrates and plants – they particular like worms and snails. They have also been known to feed on dead animals lying about, – and this should make some folks happy… they like to eat cockroaches!

Males look different than females in that their plastron has a concaved depression in it and their tails are much longer. Females will usually lay about 2 eggs in a nest she digs during rainy afternoons. She will lay more than one nest each season usually producing about 9 eggs each year. Baby box turtles are usually dark brown with a yellow stripe running down the middle of their carapace.

Many turtles, eggs, and hatchlings are lost to predators. Fire ants are a big problem as are birds, mammals and reptiles. Scarlet snakes are particularly good at finding nests. Most adults’ bare scars from attacks but usually survive by withdrawing into their shells. One animal, the wild pig, is believed to be strong enough to crush the entire shell consuming the turtle. Raccoons are also good at grabbing a limb before they can withdraw – there are many 3-legged box turtles running around, but they seem fine and still hunt well.

Gulf Coast box turtle heading across an open field.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

One problem they do have is fire. They prefer wooded areas, even the flowerbeds around your house. They do not dig burrows like the gopher tortoise but rather make “forms” in the pine straw or leaves – where they spend the cold and hot days of the year – they also do not like low humidity days and will build forms during these times as well – but these do not protect them from fires, whether wildfires or prescribed ones.

Despite all of this – they are one of the longer-lived turtles in our state. Though most do not reach the age of 40 years these days, they have the ability to reach 100!

No doubt this is one of the coolest turtles we have – and we really enjoy encountering them. Take a walk around after a rainy day and see if you can find one in your yard!

References

Meylan P.A. (Ed). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 5, 2020

We began this series on the Gulf talking about the Gulf itself. We then moved to the big, more familiar – maybe more interesting animals, the vertebrates – birds, fish, etc. In this edition we shift to the invertebrates – the “spineless” animals of the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them we know from shell collecting along the beach, others are popular seafood choices, but most we know nothing about and rarely see.

A spineless Comb Jelly.

Florida Sea Grant

They are numerous, on diversity alone – making up 90% of the animal kingdom. They may leave remnants behind so that we know they are there. They may be right in front of our faces, but we do not know what we are looking at. They are incredibly important. Providing numerous nutrient transport, and transfer, in the ecosystem – that would otherwise not exist. They also provide a lot of ecological services that reduce toxins and waste. One source suggests there are over 30 different phyla and over one million species of invertebrates. In this series we will cover six major groups and we begin with the simplest of them all… the sponges.

For some, you may not know that sponges are actually alive. For others, you knew this but were not sure what kind of creature it was. Are they plants? Animals? Just a sponge?

The answer is animal. Yea…

We usually think of animals as having legs, running around, eating things and defecting in places – the kinds of things that make good animal planet shows.

Sponges… would not make a great animal planet show. What are you going to watch? They appear to be doing nothing. They sit on the ocean floor… and… well… that’s it, they sit on the ocean floor. But they actually do a lot.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

They are considered animal because (a) their cells lack a cell wall – which plants have, and (b) they are heterotrophic… consumers… they have to hunt their food and cannot make it as plants do.

What do they eat?

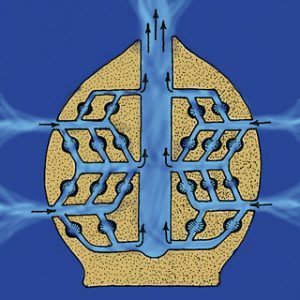

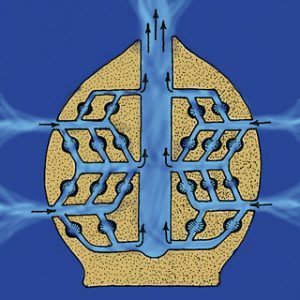

Plankton. Lots of plankton. Looking at a sponge you would call it one animal, but it is actually a colony of specialized cells working as a unit to survive. There are cells with flagella, called collar cells, that use these flagella to create currents that “suck” water into the body of the creature. This is how they collect plankton. The collar cells live in numerous channels throughout the sponge body connected to small pores all over the service of the sponge. This is where they get their phylum Porifera. As the water moves through the channels, the collar cells remove food and specialized cells called choanocytes release reproductive eggs called gemmules. All of the water eventually collects in a cavity, called the gastrovascular cavity where it exists the sponge through a large opening called an osculum.

This is how they eat and reproduce.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

The matrix, or tissue, of the sponge is held together by small, hard structures called spicules. It sort of serves as a skeleton for the creature. In different sponges the spicules are made of different materials, and this is how the creatures are divided into classes. Some are made of calcium carbonate, like seashells. Others are made of silica and are “glass-like”, and some made of a softer material called “spongin”, which are the ones we use to take baths with. Today purchased sponges are synthetic, not natural – but you can still get natural sponges.

Many sponges are tiny, others are huge. They all like seawater – not big fans of freshwater – and many produce mild toxins to defend the from predators. They do have predators though – hawksbill sea turtles love them. There is currently a lot of research going on using sponge toxins to kill cancer cells. Who knows, the cure to some forms of cancer may lie in the cavity of the sponge.

Another cool thing about them is that their cavities provide a lot of space for other small creatures in the ocean. Numerous species can be found in sponge tissue and cavities, utilizing this space as a habitat for themselves.

Florida Sea Grant

They are a major player in the development of reefs in the tropics and, like their counter parts coral, have experienced a decline due to over harvesting and harmful algal blooms. There are efforts in the Florida Keys to grow new sponge in aquaculture facilities and “re-plant” in the ocean. In the northern Gulf they are more associated with seagrass beds.

These are truly amazing creatures and the more we learn about them, the more amazing they become.

References:

Myriad World of the Invertebrates. EarthLife. https://www.earthlife.net/inverts/an-phyla.html.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2020

Article By: Whitney Cherry

4-H Agent Calhoun County

I know COVID-19 has been driving public and private discussion as of late. But, we have to stay vigilant in working against all public health threats. One of those threats we typically start talking about this time of year is mosquito borne illnesses and preventative mosquito control. Not only are mosquitoes pests, but they can transmit some pretty nasty diseases we wouldn’t want under normal circumstances. But with our healthcare system currently inundated with COVID-19 patients, we certainly wouldn’t want to unnecessarily add to the burden.

Adult female yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus), in the process of seeking out a penetrable site on the skin surface of its host.

Credit: James Gathany, Center for Disease Control Public Health Image Library Source: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in792

So what’s the reality? While the incidence of mosquito borne illness is much lower with the advent of modern medicine and basic public practices of wearing bug spray and dumping or treating standing water, it’s definitely not unheard of. The Zika scare is not such a distant memory after all. And EEE (eastern equine encephalitis) was at an unusual high last year in horses in the panhandle. So what can we do?

With recent flooding in some areas and the weather warming, we can expect to see increasing populations of mosquitoes. Additionally, as the weather warms, we all tend to spend more time outside, increasing our likelihood of mosquito bites. Further exacerbating the situation is the widespread quarantine measures keeping many of us home. The late afternoon and early evening hours bring ideal weather to step outside and enjoy a little time away from TV and computer screens. We encourage fresh air and exercise outdoors, but we also encourage basic safety. So wear bug spray if you’re outside early morning and especially near, during, or shortly after dusk. Wear long sleeves and pants and socks if you can stand it. And keep standing water dumped out of containers on your property. If this isn’t possible, look for safe water treatment options. The most prevalent spreaders of disease (Aedes aegypti) actually require these containers of water to complete their lifecycle.

For more information on this or other Extension-related topics, call or email your local extension office.

Related information: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/results.html?q=mosquito+borne+illness&x=0&y=0#gsc.tab=0&gsc.q=mosquito%20borne%20illness&gsc.page=1

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 20, 2020

As with mud turtles, full grown musk turtles are no bigger than your hand. They differ from mud turtles in that they have a single hinge on their plastron and the scutes just above that hinge are rectangular instead of triangular. Like mud turtles, they are very aquatic and not seen basking or out of water at anytime other than to lay eggs. Also like mud turtles, few people know they exist.

There are only two species in Florida, the Loggerhead Musk (Sternotherus minor) and the Common Musk (Sternotherus odoratus). There is a subspecies of the Loggerhead Musk in the far western panhandle, the striped-necked (Sternotherus minor peltifer).

Loggerhead Musk Turtle.

Photo: Flickr

The Loggerhead Musk is found through much of the southeastern United States and much of Florida. Like all musk and mud turtles it is small, with an average carapace length of 6 inches. The carapace will have 3 keels and small black flecks scattered across the light brown/olive colored shell. The head is large and wide with large jaws for crushing mollusk shells, a favorte food. The head is light colored with dark markings and 2 barbels (fleshy whiskers) under the chin. These barbels are chemosynthetic and help locate food. There are no striped on the head.

They prefer to walk across the bottom of either calm or flowing waterways, rarely leaving the water and have been found as deep as 44 feet into springs. In the waterways where they are found they have some of the highest densities of any turtle in the area – as much as 3000 individuals in a hectare. They breed in both fall and spring and the female usually does not travel far from the water to lay her eggs. Eggs have been found near logs and stumps. She will usually lay about 1-5 and they may take 100 days to incubate. Loggerheads feed on insects when young and switch to mollusk as adults. They have been known to eat other small turtles in captivity. They are preyed upon by alligator snapping turtles and maybe the alligator itself. They have been popular in the pet trade.

This common musk turtle (stinkpot) shows the dark head with stripes but also shows at bullet hole from a practice by some people called “plinking”. Where they practice shooting at turtles.

The Common Musk turtle is just that… common. It is found across the entire eastern portion of the United States and all of Florida. As its scientific name suggests (S. odoratus) it releases a pungent musk from glands near the bridge between the carapace and the plastron. This strong musk gives the turtle is other common name “Stinkpot”.

It too has a carapace about 6 inches long but differs from the Loggerhead in that its head is dark with 2 Yellow-White stripes running laterally. There is also a notch in the plastron near the tail. It is very aquatic, and can be found in high densities, but prefers still quite waters. They are known to be deep divers as well, diving to depths of 30 feet.

They will nest more inland than Loggerheads and usually lay multiple clutches of 1-9 eggs sometimes not burying them. Stinkpots are omnivorous, preferring mollusk but will also consume other invertebrates and seeds. Being small, they are preyed upon by raccoons, wading birds, fox, skunks, water snakes, hawks, eagles, alligators, snapping turtles, bull frogs, and even large mouth bass.

The handling of small turtles must be done with care. They have a long reach and nasty bite. But they are very cool turtles and very common. It is very cool to see them while snorkeling or paddling our rivers and springs.

Resource:

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.). 2005. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 3, 376 pp.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.