by Rick O'Connor | Jan 29, 2020

If you ask a kid who is standing on the beach looking at the open Gulf of Mexico “what kinds of creatures do you think live out there?” More often than not – they would say “FISH”.

And they would not be wrong.

According the Dr. Dickson Hoese and Dr. Richard Moore, in their book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, there are 497 species of fishes in the Gulf. However, they focused their book on the fish of the northwestern Gulf over the continental shelf. So, this would not include many of the tropical species of the coral reef regions to the south and none of the mysterious deep-sea species in the deepest part of the Gulf. Add to this, the book was published in 1977, so there have probably been more species discovered.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski

Fish are one of the more diverse groups of vertebrates on the planet. They can inhabit freshwater, brackish, and seawater habitats. Because all rivers lead to the sea, and all seas are connected, you would think fish species could travel anywhere around the planet. However, there are physical and biological barriers that isolate groups to certain parts of the ocean. In the Gulf, we have two such groups. The Carolina Group are species found in the northern Gulf and the Atlantic coast of the United States. The Western Atlantic Group are found in the southern Gulf, Caribbean, and south to Brazil. The primary factors dictating the distribution of these fish, and those within the groups, are salinity, temperature, and the bottom type.

Off the Texas coast there is less rain, thus a higher salinity; it has been reported as high 70 parts per thousand (mean seawater is 35 ppt). The shelf off Louisiana is bathed with freshwater from two major rivers and salinities can be as low as 10 ppt. The Florida shelf is more limestone than sand and mud. This, along with warm temperatures, allow corals and sponges to grow and the fish assemblages change accordingly.

Some species of fish are stenohaline – meaning they require a specific salinity for survival, such as seahorses and angelfish. Euryhaline fish are those who have a high tolerance for wide swings in salinity, such as mullet and croaker.

Courtesy of Florida Sea Grant. In total, it takes about 3 – 5 years for reefs to reach a level of maximum production for both fish and invertebrate species.

Forty-three of the 497 species are cartilaginous fish, lacking true bone. Twenty-five are sharks, the other 18 are rays. Sharks differ from rays in that their gill slits are on the side of their heads and the pectoral fins begins behind these slits. Rays on the other hand have their gill slits on the bottom (ventral) side of their body and the pectoral begins before them. Not all rays have stinging barbs. The skates lack them but do have “thorns” on their backs. The giant manta also lacks barbs.

Sharks are one of the more feared animals on the planet. 13 the 25 species belong to the requiem shark family, which includes bull, tiger, and lemon sharks. There are five types of hammerheads, dogfish, and the largest fish of all… the whale shark; reaching over 40 feet. The most feared of sharks is the great white. Though not believed to be a resident, there are reports of this fish in the Gulf. They tend to stay offshore in the cooler waters, but there are inshore reports.

The impressive jaws of the Great White.

Photo: UF IFAS

There is great variety in the 472 species of bony fishes found in the Gulf. Sturgeons are one of the more ancient groups. These fish migrate from freshwater, to the Gulf, and back and are endangered species in parts of its range. Gars are a close cousin and another ancient “dinosaur” fish. Eels are found here and resemble snakes. As a matter of fact, some have reported sea snakes in the Gulf only to learn later they caught an eel. Eels differ from snakes in having fins and gills. Herring and sardines are one of the more commercially sought-after fish species. Their bodies are processed to make fish meal, pet food, and used in some cosmetics. There are flying fish in the Gulf, though they do not actually fly… they glide – but can do so for over 100 yards. Grouper are one of the more diverse families in the Gulf and are a popular food fish across the region. There untold numbers of tropical reef fish. Surgeons, triggerfish, angelfish, tangs, and other colorful fish are amazing to see. Stargazers are bottom dwelling fish that can produce a mild electric shock if disturbed. Large billfish, such as marlins and sailfins, are very popular sport fish and common in the Gulf. Puffers are fish that can inflate when threatened and there are several different kinds. And one of the strangest of all are the ocean sunfish – the Mola. Molas are large-disk shaped fish with reduced fins. They are not great swimmers are often seen floating on their sides waiting for potential prey, such as jellyfish.

We could go on and on about the amazing fish of the Gulf. There are many who know them by fishing for them. Others are “fish watchers” exploring the great variety by snorkeling or diving. We encourage to take some time and visit a local aquarium where you can see, and learn more about, the Fish of the Gulf.

Reference

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M University Press. College Station Texas. Pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 21, 2020

There are a couple of things you learn when working with youth in turtle education.

1) ALL turtles are snapping turtles

2) Snapping turtles are dangerous

I grew up in a sand hill area of Pensacola and we found box turtles all of the time. We had one as a “pet” and his name was “Snappy”. Oh, I forgot… all turtles are males.

That said, others are well aware of this unique species of turtle in our state. It does not look like your typical turtle. (1) They are large… can be very large – some male alligator snappers have weighed in at 165 lbs.! (2) Their plastron is greatly reduced, almost not there. Because of this their legs can bend closer to the ground and walk more like dogs than other turtles do. We call this cursorial locomotion. Snappers are not cursorial, but they are close, and because of this can move much faster across land. (3) Their carapace is almost square shaped (versus round or oval) and have large ridges making them look like dinosaurs. (4) They have longer tails than most turtles, some species have scales pointing vertically making them look even more like dinosaurs. Scientists have wondered whether this unique reduced plastron-better locomotion design was the original for turtles (and they lost it), or they are the “new kids on the block”. The evidence right now suggests they are “the new kids”.

The relatively smooth shell of a common snapping turtle crossing a highway in NW Florida.

Photo: Libbie Johnson

And of course, there is the “SNAP”. These are very strong animals who seem to crouch and lunge as they quickly SNAP at potential predators – as quickly as 78 milliseconds/bite. I remember once stopping on a rural highway to get one out of the road. I grabbed it safely behind the nape and near the rear. That sucker crouched and snapped, and I could hardly hold on. I was amazed by its strength. It did not understand I was trying to help. You do need to be careful around these guys.

In Florida, we have two species of snapping turtles; the common and the alligator. They look very similar and are often confused (everyone seen is called an alligator snapper). There are couple of ways to tell them apart.

1) The alligator snapper has a large head with a hooked beak.

2) The alligator snapper’s carapace is slightly squarer and has three ridges of enlarged scales that make it look “spiked”; where the common snapper lacks these.

3) The tail of the common snapper has vertical “spiked” scales; which the alligator lacks.

4) And the textbook range of the alligator snapper is the Florida panhandle. Basically, if you are south or east of the Suwannee River, it should not be around – you are seeing the common.

As the name implies, the common snapper (Chelydra serpentina) is found throughout the state – except the Florida Keys. There are actually two subspecies; the Common (C. serpentia serpentina) which is found west of the Suwannee River and the Florida Snapper (C. serpentina osceola). This species uses a wide range of habitats. They have been found in small creeks, ponds, floodplain swamps, wet areas of pine flatwoods, and on golf courses.

These are very mobile turtles, often seen crossing highways looking for nesting locations, dispersing to new territory, or their pond has just dried up and they need a new one. Interestingly they have an expanded diet. Most think of snapping turtles as fish eaters, but common snappers are known to consume large amounts of aquatic plants and invertebrates.

Like all turtles, snappers must find high-dry ground for nesting. Nesting begins around April and runs through June. In south Florida, nesting can begin as early as February. They select a variety of habitats and typically lay 2-30 eggs deep in the substrate. These incubate for about 75 days and the temperature of the egg determines its sex; warmer eggs produce females. Nest predation is a problem for all turtles, snappers are not exempt from this. Raccoons are the big problem, but fish crows, fox, and possibly armadillos also dig up eggs. Many adults have been found with leeches. Turtles are known to live long lives. Data suggests common snappers reach 50 years of age.

Alligator snappers (Macrochelys temminckii) are the big boys of this group. Where the common snapper’s carapace can reach 1.5 feet, the alligator snapper can reach 2.0. (that’s JUST the shell). As mentioned, this animal is found in the Florida panhandle only. It is a river dweller and prefers those with access to the Gulf of Mexico. They appear to have some tolerance of brackish water. One alligator snapper near Mobile Bay AL had barnacles growing on it. Evidence suggest they do not move as much as common snappers and stay in the river systems where they were born. There are three distinct genetic groups: (1) the Suwannee group, (2) the Ochlocknee/Apalachicola/Choctawhatchee group, and (3) the Pensacola Bay group.

The ridged backs of the alligator snapping turtle. Photo: University of Florida

This animal is more nocturnal than their cousin and are not seen very often. They are basically carnivores and known to feed on fish, invertebrates, amphibians, birds, small mammals, reptiles, small alligators, and acorns are common in their guts. This species possesses a long tongue which they use as a fishing lure to attract prey.

Alligator snappers have a much shorter nesting season than most turtles; April to May. And, unlike other turtles, only lay one clutch of eggs per season. They typically lay between 17-52 eggs, sex determination is also controlled by the temperature of the incubating egg, and they may have strong site fidelity with nesting. Male alligators are very aggressive towards each other in captivity. This suggests strong territorial disputes occur in the wild. These live a bit longer than common snappers; reaching an age of 80 years.

Though still common, both species have seen declines in their populations in recent years. Dredge and fill projects have reduced habitat for the common snapper. Dams within the rivers and commercial harvest have impacted alligator snapper numbers. The alligator snapper is currently listed as an imperiled species in Florida and is a no-take animal (including eggs). Because the common snapper looks so similar, they are listed as a no-take species as well.

Both of these “dinosaur” looking creatures are amazing and we are lucky to have them in our backyards.

References

Meylan P.A. (Ed). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

FWC – Freshwater Turtles

https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 8, 2020

How cool, there is nothing wrong with other animals, but how cool for a year to be dedicated to turtles. And how fitting for the Florida panhandle. Based on the publication Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles (2006), there are 38 taxa of turtles in our state. The majority of these can be found in the panhandle, particularly near the Apalachicola and Escambia Rivers. Within our state some species are only found at these two locations, and some are only found there on the planet.

A terrestrial gopher tortoise crossing the sand on Pensacola Beach.

Photo: DJ Zemenick

Everyone loves turtles.

I hear a lot of stories about families trying to rescue while they are crossing highways. And when it comes to conservation, most will tell you “don’t mess with the turtles”. They are not kola bears… but they’re close. So, we are excited that 2020 is not only the year to Embrace the Gulf of Mexico, but also the Year of Turtle, and we plan to post one article a month highlighting the species richness of our area.

Let’s start with turtles in general.

Most know they are vertebrates but may not know the backbone and ribs support the framework for their famous shell. The top portion of this shell, where the backbone is, is called the carapace. The hard portion covering their chest area is the plastron. And they are connected by the bridge. The shell is a series of bony plates covered with scales (scutes). These scales are what put them in the class Reptilia. Fish also have scales but differ from reptiles in that they have gills instead of lungs. Most turtles are excellent swimmers, but they must hold their breath underwater, and some can do this for quite a long time.

All turtles are in the same Order Chelonia. The terms tortoise and terrapin are more cultural than biological. There are 7 families, and 25 species, of turtles found in Florida. Some are marine, and some terrestrial, but most are what we call “riverine”, living in freshwater.

This aquatic Florida Cooter was found crossing a locals yard.

Photo: Deb Mozert

Turtles lack teeth but do have a blade like beak they can cut with. In general, smooth blades are carnivorous, serrated ones herbivorous, and their omnivorous turtles as well. Most prey are small, and most carnivores must conceal themselves to ambush their prey. Though depicted as slow animals in fairy tales and stories, turtles can be quite fast for a few seconds.

Most are diurnal (active during daylight hours) but some nocturnal activity does occur. They spend parts of their day basking on logs and other platforms to warm – turtles are ectothermic and rely on the sun for heat.

Mating occurs in the spring. And despite the fact that most are aquatic, nesting occurs on land for all. Except for a few live bearers, reptiles lay cledoic eggs (shelled) buried on dry ground. Sex is determined by the temperature of the egg in all except the softshell turtles, with eggs at 30° C or higher producing females.

Teaching our youth about the great diversity of Florida’s turtles.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Despite their need for warm climates, they can be found throughout the United States. But it is the warm humid southeast where they thrive. Especially the northern Gulf Coast where 60″ of rainfall each year is the norm. We will bring you an article about a new species every other week throughout this year.

Let’s Celebrate the Year if the Turtle.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 8, 2019

Over the last two years I have been surveying snakes in a local community on Perdido Key. The residents were concerned about the number of cottonmouths they were seeing and wanted some advice on how to handle the situation. Many are surprised by the number of cottonmouths living on barrier islands, we think of them as “swamp” residents. But they are here, along with several other species, some of which are venomous. Let’s look at some that have been reported over the years.

The dune fields of panhandle barrier islands are awesome – so reaching over 50 ft. in height. This one is near the Big Sabine hike (notice white PVC markers).

In the classic text Handbook of Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida; Part One – Snakes (published in 1981), Ray and Patricia Ashton mention nine species found on coastal dunes or marshes. They did not consider any of them common and listed the cottonmouth as rare – they seem to be more common today. In a more recent publication (Snakes of the Southeast, 2005) Whit Gibbons and Michael Dorcas echo what the Ashton’s published but did add a few more species, many of which I have found as well. Their list brings the total to 15 species. I have frequently seen four other species in Gulf Breeze and Big Lagoon State Park that neither publication included, but I will since they are close to the islands – this brings the total 19 species that residents could encounter.

Leading us off is the one most are concerned about – the Eastern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorous). Though listed as “rare” by the Ashton’s, encounters on both Pensacola Beach and Perdido Key are becoming common. There is more than one subspecies of this snake – the eastern cottonmouth is the local one – and that the water moccasin and cottonmouth are one in the same snake. This snake can reach 74 inches in length (6ft). They are often confused with their cousin the copperhead (Agkistrodon contorix). Both begin life in a “copper” color phase and with a luminescent green-tipped tail. But at they grow, the cottonmouth becomes darker in color (sometimes becoming completely black) while the copperhead remains “copper”. The cottonmouth also has a “mask” across its eyes that the copperhead lacks. Believe it or not, the cottonmouth is not inclined to bite. When disturbed they will vibrate their tail, open their mouth showing the “cottonmouth” and displaying their fangs, and swiveling their head warning you to back off. Attacking, or chasing, rarely happens. I find them basking in the open in the mornings and seeking cover the rest of the day. Turning over boards (using a rake – do not use your hand) I find them coiled trying to hide. MOST of the ones I find are juveniles. These are opportunistic feeders – eating almost any animal but preferring fish. They hunt at night. Breeding takes place in spring and fall. The females give live birth in summer. As mentioned earlier, they seem to be becoming more common on our islands.

Eastern Cottonmouth with distinct “mask” and flattened body trying to intimidate.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This year, while surveying for cottonmouths, I encountered numerous Eastern Coachwhips (Masticophis flagellum). These long slender snakes can reach lengths of 102” (8ft.), move very fast across the ground – often with their heads raised like a cobra – and, even though nonvenomous, will bite aggressively. They get their name from their coloration. They have a dark brown head and neck and a tan colored body – resemble an old coachwhip. They like dune environments and are excellent climbers. They consume lizards, small birds and mammals, and even other small snakes. They are most active during the daylight, but I usually find them beneath boards and other debris hiding. They have always been on the islands but encountered more often this past year. They lay eggs and do so in summer.

Their close cousin, the Southern Black Racer (Coluber constricta) is very similar but a beautiful dark black color. They can reach lengths of 70” (6ft.) and are also very fast. Like their cousin, they are nonvenomous but bite aggressively – often vibrating their tail like cottonmouths warning you to stay back. They are beneficial controlling amphibian, reptile, and mammalian animals. They are also summer egg layers.

The southern black racer differs from otehr black snakes in its brillant white chin and thin sleek body.

Photo: Jacqui Berger.

There are a few freshwater snakes that, like the cottonmouth do not like saltwater, but could be found on the islands. These are in the genus Nerodia and are nonvenomous. There are two species (the Midland and Banded water snakes) that could be found here. They resemble cottonmouths in size and color and are often confused with them. They differ in that they have vertical dark stripes running across their jaws and have a round pupil. Though nonvenomous, they will bite aggressively. One member of the Nerodia group is the Gulf Coast Salt Marsh Snake (Nerodia clarkii clarkii). This snake does like saltwater and is found in the brackish salt marshes on the island. It is dark in color with four longitudinal stripes, two are yellow and two are a dull brown color. It only reaches a length of 36” (3ft.), is nocturnal, and feeds on estuarine fish and invertebrates.

This banded water snake is often confused with the cottonmouth. This animal has the vertical stripes extending from the lower jaw, which is lacking in the cottonmouth.

Photo: University of Georgia

Other species that the guides mention, or I have seen, are the small Crowned Snake, Southern Hognose, Pine Snake, Pine Woods Snake, and the Rough Green Snake. I will mention here species I have seen in either Gulf Breeze or Big Lagoon State Park that COULD be found on the island: Eastern Coral Snake, Eastern Garter Snake, Pigmy Rattlesnake, Eastern Hognose, and the Corn Snake (also called the Red Rat Snake). Only two of these (Eastern Coral and Pigmy) are venomous.

Last, but not least, is the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotolus adamateus). This is the largest venomous snake in the United States, reaching 96” (8ft.). It is a diurnal hunter consuming primarily small mammals, though large ones can take rabbits. They prefer the dry areas of the island where cover is good. Palmettos, Pine trees, and along the edge of wetlands are their favorite haunts. Despite their preference for dry sandy environments, they – like all snakes – are good swimmers and large rattlesnakes have been seen swimming across Santa Rosa Sound and Big Lagoon. They tend to rattle before you get too close and you should yield to this animal. The have an impressive strike range, 33% of their body length, you should give these guys a wide berth. I have come across several that never rattled, I just happen to see them. Again, give them plenty of room when walking by.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake swimming in intracoastal waterway near Ft. McRee in Pensacola.

Photo: Sue Saffron

It is understandable that people are nervous about snakes being in popular vacation spots, but honestly… they really do not like to be around people. We are trouble for them and they know it. Most encounters are in the more natural areas of the islands. Staying on marked trails and open areas, where you can see them – and be sure to look down while walking, you should see them and avoid trouble. For more questions on local snakes, contact me at the county extension office.

References

Ashton, R.E., P.S. Ashton. 1981. Handbook of Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida; Part One – Snakes. Windward Publishing, Miami FL. Pp.176.

Gibbons, W., M. Dorcas. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 253.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

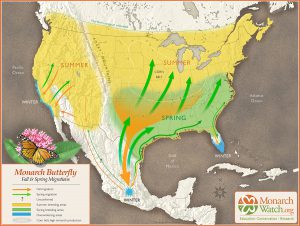

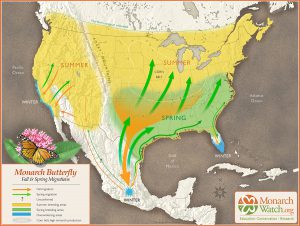

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.

by Carrie Stevenson | Sep 27, 2019

Ospreys, or fish hawks, build their nests from sticks atop dead trees. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

Big hurricanes like Dorian (Bahamas) and 2018’s Michael (central Florida Panhandle) were devastating to the communities they landed in. Flooding, wind, rain, loss of power and communications eventually made way for ad hoc clearing and cleanup, temporary shelters, and a slow walk to recovery. Among the most striking visual impacts of a hurricane are the tree losses, as there are unnatural openings in the canopy and light suddenly shines on areas that had been shaded for years. In northwest Florida, pines are particularly vulnerable. After any hurricane in the Panhandle, you can drive down Interstate 10 for miles and see endless pines blown to the ground or broken off at the top. During Hurricane Ivan 15 years ago, the coastal areas in Escambia and Santa Rosa lost thousands of trees not only due to wind, but also to tree roots inundated by saltwater for long periods.

Dead trees left by hurricanes serve as ideal nesting ground for large birds like ospreys. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Nature always finds a way, though. Because of all those dead (but still-standing) pines, our osprey (Pandion haliaetus) population is in great shape in the Pensacola area. How are these two things related? Well, ospreys build large stick nests in the tall branches/crooks of dead trees, known as snags. They particularly prefer those near the water bodies where they fish. When I first moved here 20 years ago, I rarely saw ospreys. Now, it’s uncommon not to see them near the bayous and bays, or to hear their high-pitched calls as they swoop and dive for fish.

If you are not familiar with ospreys, they can be distinguished by their call and their size (up to six foot wingspan). It is common to see them in their large nests atop those snags, flying, or diving for fish. I usually see them with mullet in their talons, although they also prey on catfish, spotted trout, and other smaller species. They have white underbellies, brown backs, and are smaller than eagles but larger than your average hawk. One of their more interesting physical adaptations (and identifying characteristics) is their ability to grip fish parallel to their bodies, making it more aerodynamic than the perpendicular method most birds use.

Ospreys mate for life, and cooperate to build nests and care for young. The species has overcome many complex threats—including DDT damage to eggs and habitat loss—but the sight of them flying is always inspiring to me. They are a living embodiment of resilience amidst adversity.