by Rick O'Connor | Aug 30, 2024

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast as well. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

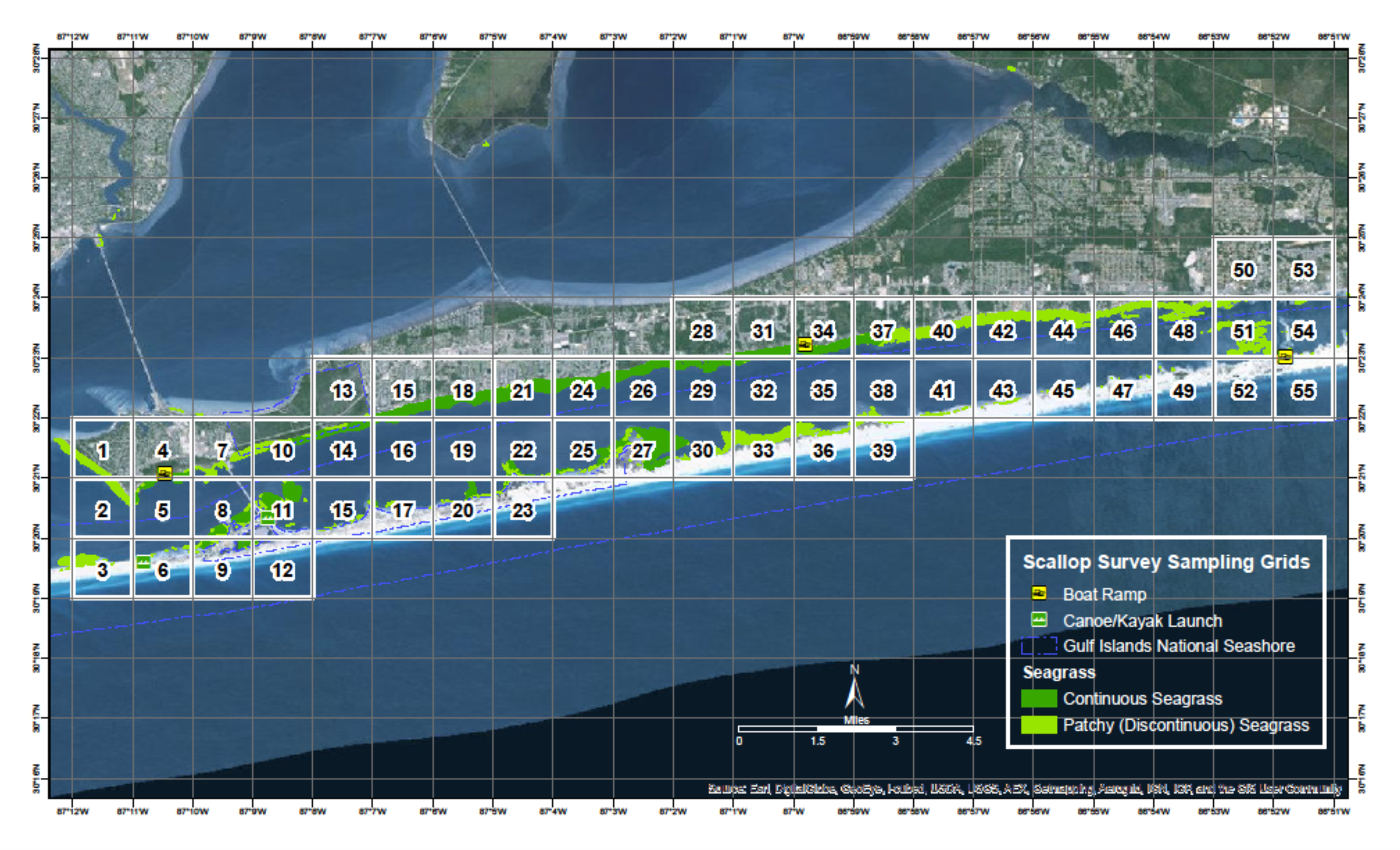

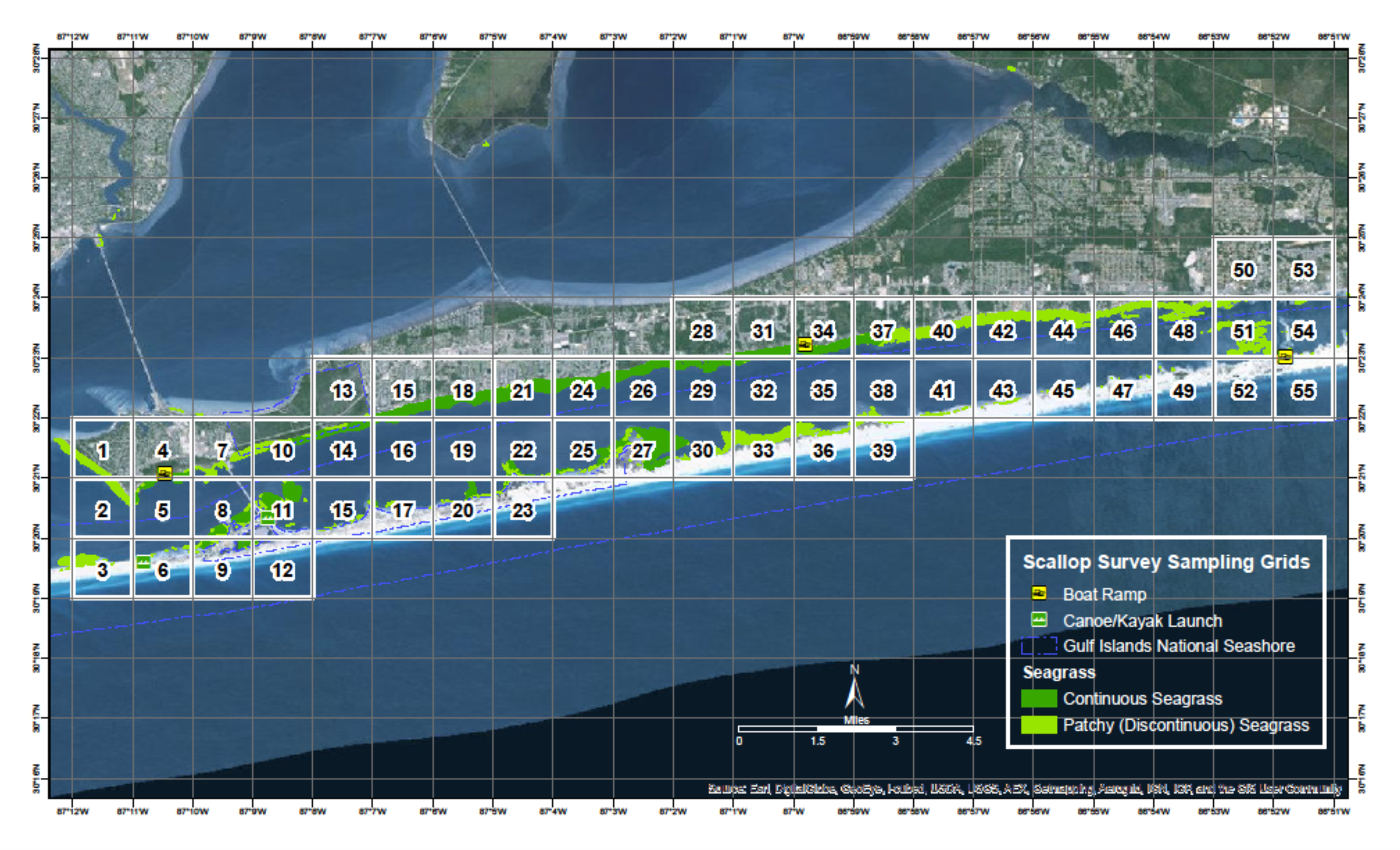

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2024 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

2024 Results

A record 168 volunteers surveyed 15 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (23%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 152 transects (15,200m2) were surveyed logging 133 scallops. An additional 50 scallops were found outside the official transect for a total of 183 scallops for 2024.

2024 Big Lagoon Results

75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids (64%) within the Big Lagoon. 67 transects were conducted covering 6,700m2.

101 scallops were logged with an additional 42 found outside the official transects. This equates to 3.02 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs and conchs, both scallop predators, as well as some sea urchins. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in six of the seven grids (86%) but was never abundant.

2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

93 volunteers surveyed 8 of the 55 grids (14%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 85 transects were conducted covering 8,500m2.

32 scallops were logged with an additional 8 found outside the official transects. This equates to 0.76 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and sand dollars. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in five of the eight grids (62%) and was abundant in grids surveyed on the eastern end of the survey area.

2015 – 2024 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

323 |

104 |

0.64 |

2015 – 2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

1731 |

36 |

0.42 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. However, you will notice that in 2024 the population in Big Lagoon moved from collapsed to vulnerable for this year alone.

There are some possible explanations for this.

- The survey effort in Big Lagoon was stronger than Santa Rosa Sound. 75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids. This equates to 11 volunteers / grid surveyed and 64% of the survey area was covered. With Santa Rosa Sound there were 93 volunteers who surveyed 8 of the 55 grids. This equates to 12 volunteers / grid surveyed but only 14% of the survey area was covered. Most of the SRS grids surveyed were in the Gulf Breeze/Pensacola Beach area. More effort east of Big Sabine may yield more scallops found.

- There is the possibility of different teams counting the same scallops. Each grid is 1-nautical mile, so the probability of one team laying their transect over an area another team did is low, but not zero.

- It is known that scallops have periodic population booms. Our search this year may have witnessed this. We will know if encounters significantly decrease in 2025.

Whether there was double counting this year or not, the frequency of encounter was much higher than in previous years. There were multiple reports from the public on social media about scallop encounters as well, and in some places we did not survey. It is also understood that scallops mass spawn. So, high density populations are required for reproductive success. The “boom” we witnessed this year suggests that there is a population of scallops – albeit a collapsed one – in our bay. It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 168 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Harbor Amiss Glen Grant Eric Stone

David Anderson Phil Harter Neil Tucker

Laura Baker Gina Hertz Christian Wagley

Melinda Bennett Sean Hickey Jaden Wielhouwer

Samantha Bergeron (USM class) John Imhof Keith Wilkins

Cheri Bone Jason Mellos Christy Woodring

Cindi Cagle Greg Patterson

Cher Clary Kelly Rysula

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found. Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

Rick O’Connor Florida Sea Grant; Escambia County

Thomas Derbes II Florida Sea Grant; Santa Rosa County

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 10, 2024

Many of us are given that Birds and the Bees talk; another majority have had to give it as an adult to their kids. It is usually an awkward talk, but someone had to step up to the plate and put on a straight face. I am happy to be the one today to discuss one section of the Birds and the Bees of the Sea, batch spawning. Batch spawning, also known as broadcast spawning, is the coordinated release of gametes (sperm and eggs) into the water column. Batch spawning is not just relegated to fish, many species of invertebrates also batch spawn. Some of the most commonly encountered batch spawners include Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus), Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica), Red Drum (Sciaenops ocellatus), Red Snapper (Lutjanus campechanus), and Gag Grouper (Mycteroperca microlepis), to name a few. In fact, most gamefish species in the Gulf of Mexico are batch spawners. This has its advantages, but also has its major disadvantages. We will dive headfirst into a few representative species of saltwater organisms that batch spawn, and their respective life stages to help shed some light on reproduction in the marine world.

Baby Snapper – Thomas Derbes II

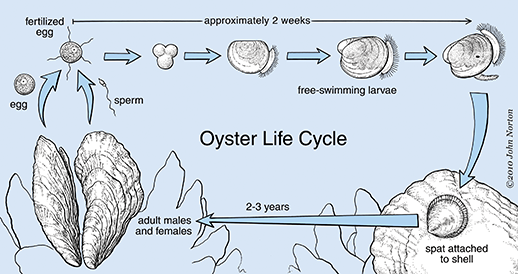

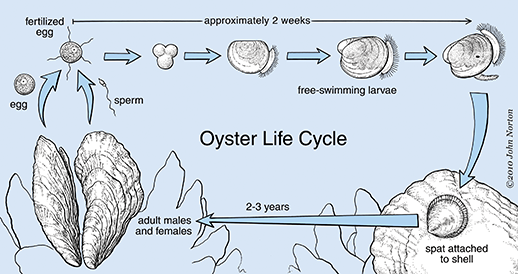

Eastern Oysters are a perfect representative for invertebrate batch spawning. I have gone over their life cycle in a previous article (Click Here), but I will just quickly go over their spawning habits and life history. Eastern Oysters typically spawn during the changing of the seasons, particularly from Spring to Summer and Summer to Fall. As humans, we see these changing temperatures and weather fronts as an opportunity for a new wardrobe, but these changes are triggers for oysters to spawn. Once one oyster releases their gametes into the water all of the mature oysters in the area will start releasing their gametes. Waiting to sense for other gametes in the water is a very smart tactic. This allows for a coordinated spawn between masses of oysters and (hopefully) increases the fertilization rate of the eggs. Since oysters cannot move, batch spawning is the most beneficial way for them to reproduce. Females can release anywhere from 2 to 70 million eggs in one spawning event, with only a dozen or so becoming adults. Since they are batch spawners, the larvae are left unprotected by the parents and suspended in the water column for the first few weeks, leaving them susceptible to predation by filter feeders and bad water quality. Once the larvae have reached the pediveliger stage, they will settle out and “walk” along the bottom of the estuary until they find a suitable place to call home, usually another oyster or hard substrate. After 1-3 years, the oyster will mature and begin batch spawning when conditions are ripe, and the cycle continues!

The Oyster Life Cycle – Maryland Sea Grant

Fish in the Lutjanidae (snapper) family are the perfect representative for batch spawning with fish. Snappers of all species are known to congregate and have mass spawning events typically around a full moon. The mutton snapper (Lutjanus analis) of South Florida and the Florida Keys are very well known for their ability to form massive congregations of tens of thousands of fish along the reef starting in April. Once the spawning commences, the mutton snapper will form a small subgroup of up to 20 fish in the late afternoon. This subgroup will travel to depths of up to 100ft to perform their spawning event. During this event, the female will signal to the males that she is about to release her eggs. The males will then rub up against the side of the female snapper, helping her release eggs while simultaneously releasing their milt (sperm). When the milt is released, the sperm is activated by the seawater and begins to swim. Eventually, the eggs are fertilized and an embryo is formed.

Massive Two-spot red snapper aggregation ready to spawn in Palau – R.J. Hamilton

18 – 24 hours later, the embryo is now a larval fish consisting of a yolk sac and lacking a mouth, eyes, and most organs. The yolk sac consists of amino acids and other nutrients that provide energy to the developing larvae. These larval fish have until their yolk sac runs out to develop the lacking vital organs, which usually takes between 24 – 48 hours. Only a very small percent of juvenile snapper make it to adulthood due to predation during their larval stage and predation as a juvenile. In fact, sharks and other large predators will prey on the snapper as they congregate and spawn, and filter feeders like manta rays are known to pass through an active spawning congregation to consume all the fertilized eggs and larval fish.

Well, I hope I didn’t scar anyone too badly. Batch spawning is fairly common in the marine biology world, and you can sometimes experience a spawning event without even knowing it. As for positives, this allows for many eggs to be fertilized at a time multiple times a season and for the larval fish and shellfish to be distributed through the estuary and reef via tides and waves. A major negative is the vulnerability of the juvenile and larval fish and shellfish, but the sheer number of eggs produced and fertilized helps outweigh the high potential for predation and unexplained loss of fertilized eggs and juveniles.

References:

Oyster Spawning: https://www.umces.edu/news/the-life-of-an-oyster-spawning

Mutton Snapper Species Spawning Profile: https://geo.gcoos.org/restore/species_profiles/Mutton%20Snapper/

Mutton Snapper Aquaculture Profile: https://srac.msstate.edu/pdfs/Fact%20Sheets/725%20Species%20Profile-%20Mutton%20Snapper.pdf

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I bet that for most of you, this is not only a worm you have never seen – it is a worm you have never heard of before. I learned about them first in college, which was almost 50 years ago, and have never seen one. But, other than the earthworm, the world of worms is basically hidden from us.

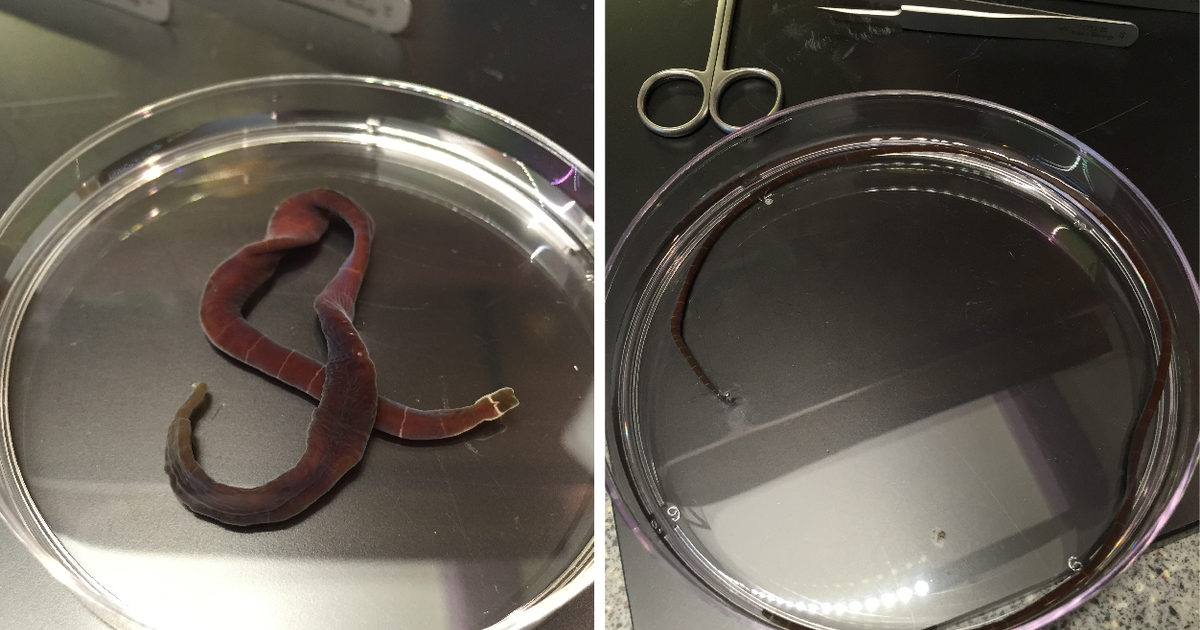

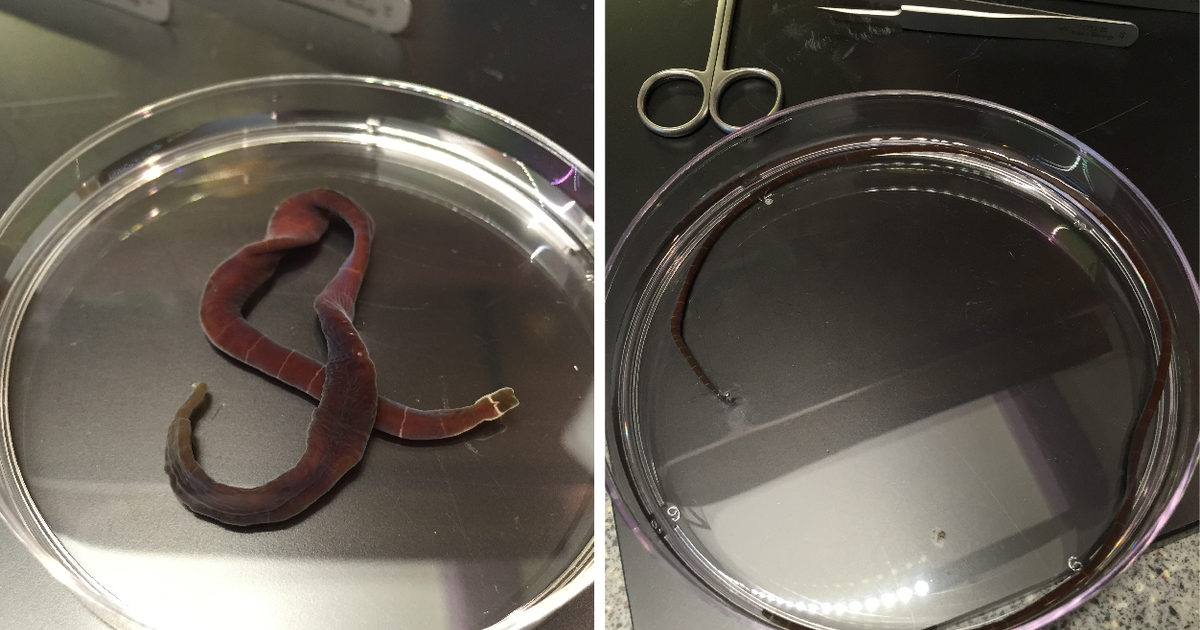

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

Nemerteans are a group of about 1300 species in the Phylum Nemertea and are often called ribbon or proboscis worms. They do possess a proboscis used to capture prey. Most are marine and live on the bottom both near the beach and a great depth. They are more temperate than tropical and do have a few parasitic forms.

Adult Nemertea Worms – Terra C. Hiebert, PhD, Oregon University

In appearance they resemble flatworms but are larger and more elongated. Most are less than 20cm (8in) but some species along the Atlantic coast can reach 2m (7ft). The head end can be lobed or even spatula looking. Some species are pale in color and others quite colorful. Most nemerteans move over the substrate on a trail of slime produced by their skin. Some species can swim.

As mentioned, the proboscis is used to capture prey. It is a tube-like structure held in a sac near the head. When prey is detected, they can launch the proboscis out and over the victim. Sticky secretions help hold on to the prey while they ingest. Many species are armed with a stylet, dart, that is attached to the proboscis and is driven into the prey like a spear. From there toxins, secreted from the base of the proboscis are injected into the prey.

For many species the proboscis is connected to the digestive tract via a tube, there is no true mouth, but they do possess an anus. They are all carnivorous and feed on a variety of small living and dead invertebrates. Their menu includes annelid worms, mollusk, and crustaceans.

Nemerteans do possess a brain and most find their prey using chemoreception, though some species must literally bump into their prey to find it. They have multiple eyes that can detect light, and, like the true flatworms, they are negatively phototaxic. They are nocturnal by habitat and is probably why most of us have never seen one.

Many nemerteans, particularly the larger ones, have a habit of fragmenting when irritated, creating new worms. Most species have separate sexes and fertilization of the gametes is external (fertilization occurs in the environment).

Nemerteans are an interesting group of semi-large, sometimes toxic, hunters who prowl through the marine waters at night hunting prey. Seen by few, maybe one evening, while exploring or floundering, you may see one.

In Part 3 we will begin to explore a group of worms that are more round than flat. The Gastrotrichs.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I was recently conducting a survey for diamondback terrapins from my paddleboard in a small estuarine lagoon within the Pensacola Bay System. Even if we do not find our target species during these surveys – I, and our volunteers, see all sorts of other cool wildlife. On this trip I was treated to nesting osprey, a kingfisher, large blue crabs, and even a swimming eel. But one neat encounter was the numerous stingrays.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

They were lying in the sand and grassbeds, lots of them, and they all seemed to be of one species – the Atlantic stingray. My brain immediately went to “breeding season”, but when I checked the literature, I found that it was not breeding season, but pupping season – the babies were being born.

Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina) are true stingrays in the family Dasyatidae. This means they do possess the replaceable serrated venomous barb that makes these animals so famous. They are one of the smaller members of this family. Females can reach a disk width of two feet while the smaller males will only reach about one foot. Atlantic stingrays are a warm water species, migrating if they need to find suitable temperatures. They have been found in water as deep as 80 feet but are more common in the warmer shallower waters near shore. They are very common in our estuaries and being euryhaline (they tolerate a large range of salinity), are found in freshwater systems. There is a population that lives in the St. Johns River. Atlantic stingrays feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates and have special cells in the nose to detect the weak electric fields their prey give off while buried in the sediment. They also like to bury in the sand to ambush prey as they move by.

Breeding occurs in the fall. The smaller males possess two modified fins called claspers connected to their anal fins that are used to transfer sperm to the female. The males have modified teeth they can use to bite the fins of the females. They do this to hold on and make sperm transfer more successful.

The females do not begin to ovulate until spring. So, though they receive the sperm in the fall, fertilization does not occur until the spring. Instead of laying eggs, as some rays and skates do, baby Atlantic stingrays develop within the mother. This is not the same as mammals, who produce a placental to feed the developing young, but more like an internal egg with no hard shell. The embryo is attached to, and feeds from, a yolk sac. Gestation takes about 60 days at which time the yolk sac is depleted, and the young must emerge. Birth usually occurs in late July and early August, and each female will produce 1-4 small pups whose disk are about 10cm (4in.) wide. It was this birthing/pupping period I witnessed.

I returned the following day to search for terrapins and the number of stingrays was significantly fewer. It may be that the birthing process is fast, and the adults leave the coves afterwards. It may have been because that day was the day Hurricane Debby was making landfall east of us and the water levels were abnormally high – something the rays may have noticed and decided to leave – I am not sure.

I was really hoping to see the young rays swimming around – I did not – but plan to search again soon. Stingrays make many people nervous. I witnessed several adult rays whose tails had been cut off – which is very unfortunate – but they are actually cool creatures and fun to watch while paddleboarding. Maybe I will see a baby soon.

References

Dasyatis sabina. 2023. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/dasyatis-sabina/.

Johnson, M.R., Snelson Jr., F.F. 1996. Reproductive Life History of the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Pisces, Dasyatidae), in Freshwater St. Johns River, Florida. Bulletin of Marine Science, 59(1): 74-88.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 26, 2024

People enjoy animals. Zoos and wildlife parks are popular tourist destinations and animal programs are popular on television. It is usually the larger predator animals that get our attention. Sharks, panthers, and bears are popular. People like turtles, raptors, and snakes. Other animals are popular as well like antelope, elephants, and deer.

The green sea turtle.

Photo: Mike Sandler

At public aquariums you see exhibits with whales, sharks, and sea turtles. You also see tanks with reef fish, crabs, and octopus drawing crowds. But one group of animals that has never really drawn attention – either at public parks or wildlife television shows – are worms.

Worms are a world of the creepy and gross. To us, their presence suggests dirtiness or environmental problems. But worms are abundant in our environment and play an important role in ecology. In this series we will meet some of them and learn more about their lives. We begin with the flatworms.

As the name suggests, flatworms have flat bodies. In many species their heads can be identified by the presence of eyespots. Eyespots differ from eyes in that they detect light, but do not provide an actual image. Biologists describe animals as being either positively or negatively phototaxic. Most flatworms are negatively phototaxic, they do not like light. To them, light indicates daytime. A time when the predators can see and attack them. So, when they detect light, they move under rocks, mud, whatever to avoid being detected.

Most flatworms are less than 10mm (0.4 in) in length, though some are 60 cm (24 inches). They possess a mouth on their belly side (ventral) and often it is in the middle of the animal, not at the head end. This mouth leads to a simple stomach, but they lack an anus so solid waste must exit the worm through the mouth – what is called an incomplete digestive system.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

One class of flatworms are the free-swimming turbellarians. Most are carnivorous, feeding on small invertebrates and dead carcasses. Some feed on sessile creatures like oysters and barnacles. And some feed on microscopic plants like diatoms. The carnivorous species wrap their prey with their bodies secreting slime over them. They engulf their prey whole. There are two classes of flatworms that are parasitic: the trematodes (flukes), and the cestodes (tapeworms).

Flatworms lack an internal body cavity (coelom) and thus lack internal organs. Not having lungs and kidneys they must take in need gases, and other materials, and well as expel nitrogenous waste, through their skin. Being flat increases their surface area and the efficiency of doing this. This is why they are flat.

Reproduction in flatworms occurs in different ways. Some will reproduce asexually by simple fission – they split apart producing two worms. Many species reproduce sexually using sperm and egg.

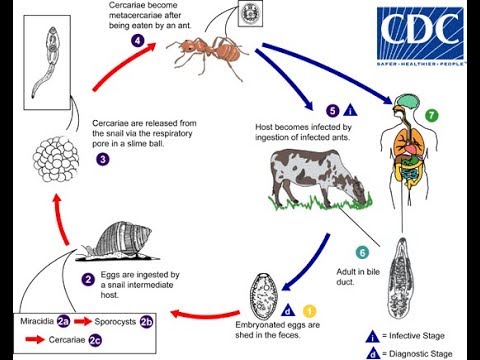

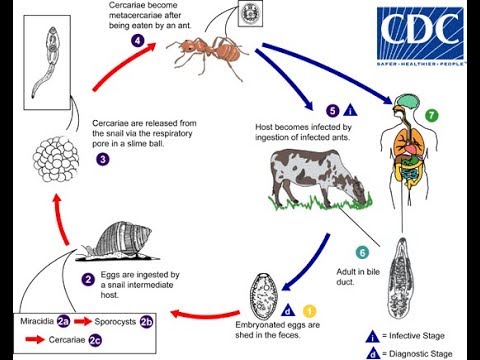

Another class of flatworms are the parasitic trematodes; commonly called flukes. They resemble turbellarians in body shape and design, though the mouth is usually at the head end. Most are only a few centimeters long, but one can reach the length of 7 meters (24 feet)! Their bodies are covered with a skin-like material that protects them from the digestive enzymes of their hosts.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

As with turbellarians, flukes are hermaphroditic but use internal fertilization with other worms to produce young, though self-fertilization can – and does – happen. Their life cycles can include one or several hosts. The primary host, the one the adults reside in, are usually vertebrates, most often fish. The intermediate hosts, the ones the juveniles reside in, are often snails but can be other species.

Life cycle of a trematode. Image: Center for Disease Control.

The life cycle is complex, but a general one would include the fertilized eggs being encased in a shell and released into the environment via the feces of the primary host. A ciliated larval stage hatches from this egg and is either consumed by the intermediate host or penetrates the skin of it. Once inside the second larval stage begins. This eventually becomes a third and fourth larval stage. At the fourth larval stage the young worm possesses a mouth and digestive tract. At this stage it leaves the intermediate host as a free-swimming larva seeking a second intermediate host. Here it goes through more larval stages and eventually becomes encased within a cyst (a hard shell). The encysted larva stage enters the primary host (a vertebrate) after that primary host consumes the second intermediate host. Here it develops into the adult trematode.

A third class of flatworms are the parasitic tapeworms – Class Cestoda. Tapeworms differ from other flatworms in that they have a round head – called a scolex – attached to a flat body, and they lack a digestive tract. The flat part of the body is made up of small square segments called proglottids. They continually add proglottids and can become quite long – some have measured over 40 feet! The scolex has four suckers and a ring of small hooks with which they can attach to the inner lining of the digestive tract with.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

The reproductive organs occur within the proglottids. Cross fertilization between these hermaphroditic worms is the rule but self-fertilization does happen. The fertilized eggs are released when the proglottid ruptures and exit the host via the feces.

Tapeworms do require intermediate hosts. The extruded egg hatches into a ciliated larva which is consumed by the intermediate host before that host is consumed by the primary host – typically a vertebrate.

As we can see the lives of these flatworms are (1) secretive, and (2) not pleasant to think about. But they do play a role in our marine and estuarine ecosystem and are very successful at what they do. They should be appreciated for their success.

In our next article on the World of Worms we will look at the nemerteans.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 21, 2024

Today’s society is more educated about sharks and shark behavior than our forefathers. In the 18th, 19th, and much of the 20th century we thought of sharks as mindless eating machines – consuming anything available. Whalers would witness sharks consuming carcasses, as did many other fishermen. Sailors noted sharks following the smaller boats across the ocean, always present when bad situations occurred.

During World War II the U.S. Navy was moving across the Pacific and a deeper understanding of sharks was needed to keep servicemen safe. The sinking of the USS Indianapolis pushed the Navy into a larger research program to determine how to repel sharks and better understand what made them tick. After the war funding for such research continued. One of the leading researchers was Dr. Eugene Clark, who eventually founded the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota with the intention of developing a better understanding of shark behavior. Dr. Clark frequently appeared on the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau educating the public about how sharks function and respond to their environment. All with the idea of how to better reduce negative shark encounters.

Pregnant Bull Shark (Carcharhinus leucas) cruses sandy seafloor. Credit Florida Sea Grant Stock Photo

In the 1970s Peter Benchley wrote Jaws but included a marine biologist as one of the key characters who would provide science insight into how sharks work. The film was a cultural phenomenon. I remember standing in a line that wrapped the cinema twice to get in. This was followed by more funding for shark research and a better understanding of how they work. This was then followed by a popular summer series known as “Shark Week”, which remains popular to this day. Many of the old tales of shark behavior were disproved or explained. The idea of a mindless eating machine was replaced with a fish that actually thinks and responds to certain cues. People began to realize that shark attacks are quite rare and could be explained if we understood what happened leading up to the attack.

We now understand that sharks are fish, in a class where the members have cartilaginous skeletons (they lack true bone). They are one of the most perceptive creatures in the ocean, using their senses to detect potential prey and that there are signals that can “turn them on”. On the side of their bodies there is a line of small gelatinous cells that can detect slight vibrations in the ocean – from up to a mile away. The ocean is a noisy place, and it appears that sharks respond to different frequencies. I like to use the analogy of yourself being in a large student cafeteria. Everyone is talking and it is very noisy. Then someone calls your name. Somehow, amongst all the background clatter, you hear this and respond to it. Studies suggest that sharks do the same. With all of the noise moving though the ocean, sharks hear things that catch their attention and then move towards the source.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

As they get closer their sense of smell kicks in. Everyone has heard that sharks can detect small amounts of blood in large amounts of seawater – remember “Bruce” from Finding Nemo? It is true, but they do have to be down current to pick up the scent and they will now focus their search to find the source. Some studies suggest other “odors”, such as the urine of seals, might produce the same reaction that blood does. All may lead to shark to think a possible meal is nearby.

Eyesight is not great with any creature in the sea. Light does not travel well in water – but sharks do have eyes and they do see well (one of the old tales science disproved – that sharks are basically “blind”). However, because of the low light, they do have to be close to the target to get a visual. Some studies suggest that sharks are detecting shadows or shapes they may confuse as a potential prey, bite it, and then release when they discover it was not what they thought it was. This idea is supported by the fact that many who are bitten experience what is called “bite and release” – and they turn and swim away. It is also known that sharks have structures in the back of their retinas that act as mirrors, collecting what light is available, reflecting it within the eye, and illuminating their world. They believe they see pretty well at night – better than us for sure. The image they see may appear to be a prey item and may be what is producing the vibrations and odors that they detected.

The Scalloped Hammerhead is one of five species of hammerheads in the Gulf. It is commonly found in the bays. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

And they have one more “sixth sense” – the ability to detect weak electric fields. The shark’s mouth is not in position to attack prey as they move forward. It is on the bottom of their head and, one of the old tales, was that sharks must swim over their prey to bite it. Video taken during the filming for Jaws showed that the shape of the shark’s head changes at the last moment of an attack. The entire head becomes distorted to get the mouth in the correct position for the bite. The “eyes roll back” – as the old fishermen used to say – and the jaws move up and forward. At this point the shark can no longer use its eyes to zero in on the target. However, they have small cells around their snout called the Ampullae of Lorenzini that can detect the small electric fields produced by muscle movement – even the prey’s heartbeat – and know where they are. But – they must be very close to the prey to detect this.

Understanding all of this gives scientists, and the public, a better idea of how sharks work. What “turns them on” and how/when they will select prey. One thing that has come from all of this is that we do not seem to be high on their target list.

The Great White shark.

Photo: UF IFAS

The International Shark Attack File is kept at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. It has cataloged shark attacks from around the world dating back to 1580. The File only catalogs UNPROVOKED attacks. With provoked attacks – those occurring while people are grabbing them, or fishing for them, or in some way provoked an attack – we understand why the shark bit the human. It is the unprovoked attacks that are of more interest. Those where the person was not doing anything intentionally to invite a shark bite, but it happened.

One thing we can tell from this data is that unprovoked attacks are not common. Since 1580, they have logged 3,403 unprovoked shark attacks worldwide. Considering how many people have swum in the ocean since 1580, this is a very small number. Note, the File is only as good as the reports it gets. In the past, many unprovoked attacks were not reported. But in our modern age of communication, it is rare that such an attack does not make the headlines today.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Of these attacks 1,640 (48%) have occurred in the United States, followed by 706 in Australia. Many have explained this by the large levels of water activities people in both countries participate in. In the US Florida leads the way with 928 unprovoked attacks (57%), most of these (351 – 34%) are from Volusia County. This may be due to breakthrough emergency communications with Volusia County and thus more reports. Many of the reports are minor, small bites from small sharks such as blacktips, but unprovoked none the less. There are 26 unprovoked attacks logged from the Florida panhandle – 3% of the state total – and most of these (n=9) were from Bay County.

When looking at what people were doing when attacked, most were at the surface and participating in some surface water activity such as surfing, skiing, boogie boarding, etc. This is followed by surface swimming or snorkeling.

This brings us to the attacks this summer in the panhandle. There have been a lot of questions as to what may have caused them. They are still assessing the situation before and during these attacks to try and determine why they happened. As we have mentioned, we have learned a lot about sharks and shark behaviors over the last 50 years and several hypotheses are open for discussion. We will see what the investigators learn. Until then, the International Shark Attack File does offer a page on how you can reduce your risk. There is “Advice to Swimmers”, “Advice to Divers”, “Color of Apparel”, “Menstruation and Sharks”, “Quick Tips”, “Advice to Spearfishers”, and “How to Avoid a Shark Attack”. Read more on these tips at https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/reduce-risk/.