by Chris Verlinde | May 1, 2020

Black Skimmers foraging for fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmers and Least Terns, state listed species of seabirds, have returned along the coastal areas of the northern Gulf of Mexico! These colorful, dynamic birds are fun to watch, which can be done without disturbing the them.

Shorebirds foraging. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Black Skimmer with a fish. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

What is the difference between a seabird and shorebird?

Among other behaviors, their foraging habits are the easiest way to distinguish between the two. The seabirds depend on the open water to forage on fish and small invertebrates. The shorebirds are the camouflaged birds that can found along the shore, using their specialized beaks to poke in the sandy areas to forage for invertebrates.

Both seabirds and shorebirds nest on our local beaches, spoil islands, and artificial habitats such as gravel rooftops. Many of these birds are listed as endangered or threatened species by state and federal agencies.

Juvenile Black Skimmer learning to forage. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult black skimmers are easily identified by their long, black and orange bills, black upper body and white underside. They are most active in the early morning and evening while feeding. You can watch them swoop and skim along the water at many locations along the Gulf Coast. Watch for their tell-tale skimming as they skim the surface of the water with their beaks open, foraging for small fish and invertebrates. The lower mandible (beak) is longer than the upper mandible, this adaptation allows these birds to be efficient at catching their prey.

Least Tern “dive bombing” a Black Skimmer that is too close to the Least Tern nest. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Adult breeding least terns are much smaller birds with a white underside and a grey-upper body. Their bill is yellow, they have a white forehead and a black stripe across their eyes. Just above the tail feathers, there are two dark primary feathers that appear to look like a black tip at the back end of the bird. Terns feed by diving down to the water to grab their prey. They also use this “dive-bombing” technique to ward off predators, pets and humans from their nests, eggs and chicks.

Least Tern with chicks. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

Both Black Skimmers and Least Terns nest in colonies, which means they nest with many other birds. Black skimmers and Least Terns nest in sandy areas along the beach. They create a “scrape” in the sand. The birds lay their eggs in the shallow depression, the eggs blend into the beach sand and are very hard to see by humans and predators. In order to avoid disturbing the birds when they are sitting on their nests, known nesting areas are temporarily roped off by Audubon and/or Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) representatives. This is done to protect the birds while they are nesting, caring for the babies and as the babies begin to learn to fly and forage for themselves.

Threats to these beautiful acrobats include loss of habitat, which means less space for the birds to rest, nest and forage. Disturbances from human caused activities such as:

- walking through nesting grounds

- allowing pets to run off-leash in nesting areas

- feral cats and other predators

- litter

- driving on the beach

- fireworks and other loud noises

Audubon and FWC rope-off nesting areas to protect the birds, their eggs and chicks. These nesting areas have signage asking visitors to stay out of nesting zones, so the chicks have a better chance of surviving. When a bird is disturbed off their nest, there is increased vulnerability to predators, heat and the parents may not return to the nest.

Black Skimmer feeding a chick. Photo Credit: Jan Trzepacz, Pelican Lane Arts.

To observe these birds, stay a safe distance away, zoom in with a telescope, phone, camera or binoculars, you may see a fluffy little chick! Let’s all work to give the birds some space.

Special thanks to Jan Trzepacz of Pelican Lane Arts for the use of these beautiful photos.

To learn about the Audubon Shorebird program on Navarre Beach, FL check out the Relax on Navarre Beach Facebook webinar presentation by Caroline Stahala, Audubon Western Florida Panhandle Shorebird Program Coordinator:

In some areas these birds nest close to the road. These areas have temporarily reduced speed limits, please drive the speed limit to avoid hitting a chick. If you are interested in receiving a “chick magnet” for your car,  to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 30, 2020

Okay, this is a gamble.

I began this series to celebrate the year of the Gulf of Mexico – “Embracing the Gulf 2020”. The idea was to write about the habitats, creatures, economic impacts, and issues surrounding the “pond” that we live on. I did a few introductory articles and then jumped right into the animals. We began with the fun ones – fish, sea turtles, whales – and now we are in the more unfamiliar – invertebrates like sponges and jellyfish.

But worms? Really? Who wants to read about worms?

A classic flatworm is this lung fluke.

Photo: Kansas State University.

Well, there are a lot of them, and they are everywhere. You will find in many sediment samples that worms dominate. They also play an important role in the marine community. They are great scavengers, cleaning the environment, and an important source of food in the food chains of the more familiar animals. But they are gross and creepy. When we find worms, we think the environment is gross and creepy – and sometimes it is, remember they CLEAN THE ENVIRONMENT. But worse is that many are parasites. Yes… many of them are, and that is certainly gross and creepy. Flukes, tapeworms, hookworms, leeches, who wants to learn amore about those? Well, honestly, parasitism is an interesting way to find food and the story on how they do this is pretty interesting… and gross… and creepy. Let’s get started.

According to Robert Barnes’ 1980 book Invertebrate Zoology, there are at least 11 phyla of worms – it is a big group. We are not going to go over all of them, rather I will focus on what I call the “big three”: flatworms, roundworms, and segmented worms. We will begin with the most primitive, the flatworms.

As the name implies, these worms are flat. They are so because they are the last of what we call the “acoelomate” animals. Acoelomates are animals that lack an internal body cavity and, thus, have no true body organs – there is no where for them to go. So, they absorb what they need, and excrete, through special cells in their skin. To be efficient at this, they are flat – this increases the surface area in contact with the environment. There are three classes of flatworms – one free swimming, and two that are parasitic.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

The free-swimming ones are called turbellarians. Most are very small, look like leaves, very colorful, and undulate as they swim near the bottom. They have “eye-like” cells called photophores that allow them to see light – they can then choose whether to move towards the dark or not. They have nerve cells but no true brain, and one only one opening to the digestive tract – that being the mouth, so they must eat and go to the bathroom through the same opening. Weirder yet, the mouth is usually in the middle of the body, not at the head end. Some are carnivorous feeding on small invertebrates, others prefer algae, others are scavengers (CLEANING THE OCEAN). They can reproduce by regenerating their bodies but most use sexually reproduction. They are hermaphrodites – being both male and female. They can fertilize themselves but more often seek out another worm. Fertilization is internal and they lay very few eggs.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

The second group are called trematodes and they are the parasites we know as “flukes”. We have heard of liver flukes in livestock and humans, but there are marine versions as well. They have adhesive organs located at the near the mouth that help hold on, and a type of skin that protects them from their hosts’ defensive enzymes. They feed on cells, mucous, and sometimes blood – yep… gross and creepy. Some are attached outside of their hosts body (ectoparasites) others are attached to internal organs (endoparasites). The ectoparasites breath using oxygen (aerobic), endoparasites are anaerobic. Like their turbellarian cousins, they are hermaphroditic and use internal fertilization to produce eggs. They differ though in that they produce 10,000 – 100,000 eggs! Their primary host (the one they spend their adult life feeding on) is always a vertebrate, fish being the most common. However, their life cycle requires the hatching larva find an intermediate host where they go through their developmental growth before returning to a primary host. These intermediate host are usually invertebrates, like snails. The eggs are released with the fish feces – a swimming larva is released – enters a snail – begins part of the developmental growth – consumed by an arthropod (like a crab) – completes development – and the crab is consumed by the fish – wah-la. The adults are usually found in the gills/lungs, liver, or blood of the vertebrate hosts. Gross and creepy.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

Better yet are the tapeworms. We have all heard of these. They are also all parasites, but all are endoparasites. Weirder, they do not have a digestive tract. Gross and creepy. Their heads are very tiny compared to their bodies and have either four sets of suckers, or hooks, to hold onto the digestive tract of their hosts (usually vertebrates). The head is actually round but the body is very flat and divided into squares called proglottids. Each proglottid gets larger as you move towards the tail and each possesses all of the reproductive material needed to produce new worms – they too are hermaphrodites. They also have a type of skin that protects them from the enzymes of their hosts. They also require an intermediate host to complete their life cycle so the proglottids will exit the hosts body via feces and complete the cycle similar to the trematodes.

I began this with a comment on how worms benefit the overall marine environment of the Gulf. It is hard to see that in these flatworms. They are either just another consumer out there, or nasty parasites others in the community must deal with. Well… we look at the roundworms next time and see what they have to offer.

Reference

Barnes, R. 1980. Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders College Press. Philadelphia, PA. pp. 1089.

by Scott Jackson | Apr 17, 2020

Florida Sea Grant is maintaining a curated list of disaster assistance options for Florida’s coastal businesses disrupted by COVID-19.

Boats at calmly at rest in Massalina Bayou, Bay County, Florida.

The list contains links to details about well- and lesser-known options and includes “quick takeaway” overviews of each assistance program. Well-funded and widely available programs are prioritized on the list. The page also houses a collection of links to additional useful resources, including materials in Spanish.

“There is a lot of information floating around out there,” says Andrew Ropicki, Florida Sea Grant natural resources economist and one of the project leaders. “We are trying to provide a timely and accurate collection of resources that will be useful for Florida coastal businesses.”

Ropicki and others on the project team stress that the best place to start an application for disaster aid is to visit with your bank or lender and the Florida Small Business Development Center (SBDC). They also suggest contacting local representatives by telephone or email and not to just rely on internet-based applications.

Overview of Selected Disaster Assistance Programs Benefiting Florida Small Businesses including Agriculture, Aquaculture, and Fisheries (COVID-19)

The project team — which includes experts from Florida Sea Grant, University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Extension, and the UF/IFAS Center for Public Issues Education — reviews the page regularly for accuracy and to include new options.

Commercial seafood is a large part of Florida’s economy and culture.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

“[I] really appreciate the outstanding work that you and FSG have done on consolidating the various types of aid available to fishermen due to the virus,” said Bill Kelly, executive director of the Florida Keys Commercial Fishermen’s Association, in a recent email. “I’ve been searching for a comprehensive listing and you just provided it.”

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 5, 2020

We began this series on the Gulf talking about the Gulf itself. We then moved to the big, more familiar – maybe more interesting animals, the vertebrates – birds, fish, etc. In this edition we shift to the invertebrates – the “spineless” animals of the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them we know from shell collecting along the beach, others are popular seafood choices, but most we know nothing about and rarely see.

A spineless Comb Jelly.

Florida Sea Grant

They are numerous, on diversity alone – making up 90% of the animal kingdom. They may leave remnants behind so that we know they are there. They may be right in front of our faces, but we do not know what we are looking at. They are incredibly important. Providing numerous nutrient transport, and transfer, in the ecosystem – that would otherwise not exist. They also provide a lot of ecological services that reduce toxins and waste. One source suggests there are over 30 different phyla and over one million species of invertebrates. In this series we will cover six major groups and we begin with the simplest of them all… the sponges.

For some, you may not know that sponges are actually alive. For others, you knew this but were not sure what kind of creature it was. Are they plants? Animals? Just a sponge?

The answer is animal. Yea…

We usually think of animals as having legs, running around, eating things and defecting in places – the kinds of things that make good animal planet shows.

Sponges… would not make a great animal planet show. What are you going to watch? They appear to be doing nothing. They sit on the ocean floor… and… well… that’s it, they sit on the ocean floor. But they actually do a lot.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

They are considered animal because (a) their cells lack a cell wall – which plants have, and (b) they are heterotrophic… consumers… they have to hunt their food and cannot make it as plants do.

What do they eat?

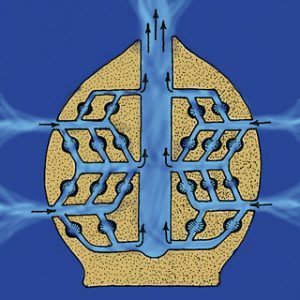

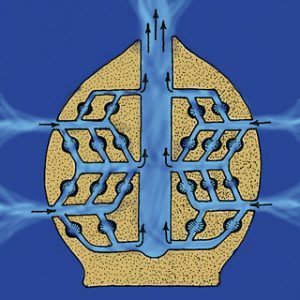

Plankton. Lots of plankton. Looking at a sponge you would call it one animal, but it is actually a colony of specialized cells working as a unit to survive. There are cells with flagella, called collar cells, that use these flagella to create currents that “suck” water into the body of the creature. This is how they collect plankton. The collar cells live in numerous channels throughout the sponge body connected to small pores all over the service of the sponge. This is where they get their phylum Porifera. As the water moves through the channels, the collar cells remove food and specialized cells called choanocytes release reproductive eggs called gemmules. All of the water eventually collects in a cavity, called the gastrovascular cavity where it exists the sponge through a large opening called an osculum.

This is how they eat and reproduce.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

The matrix, or tissue, of the sponge is held together by small, hard structures called spicules. It sort of serves as a skeleton for the creature. In different sponges the spicules are made of different materials, and this is how the creatures are divided into classes. Some are made of calcium carbonate, like seashells. Others are made of silica and are “glass-like”, and some made of a softer material called “spongin”, which are the ones we use to take baths with. Today purchased sponges are synthetic, not natural – but you can still get natural sponges.

Many sponges are tiny, others are huge. They all like seawater – not big fans of freshwater – and many produce mild toxins to defend the from predators. They do have predators though – hawksbill sea turtles love them. There is currently a lot of research going on using sponge toxins to kill cancer cells. Who knows, the cure to some forms of cancer may lie in the cavity of the sponge.

Another cool thing about them is that their cavities provide a lot of space for other small creatures in the ocean. Numerous species can be found in sponge tissue and cavities, utilizing this space as a habitat for themselves.

Florida Sea Grant

They are a major player in the development of reefs in the tropics and, like their counter parts coral, have experienced a decline due to over harvesting and harmful algal blooms. There are efforts in the Florida Keys to grow new sponge in aquaculture facilities and “re-plant” in the ocean. In the northern Gulf they are more associated with seagrass beds.

These are truly amazing creatures and the more we learn about them, the more amazing they become.

References:

Myriad World of the Invertebrates. EarthLife. https://www.earthlife.net/inverts/an-phyla.html.

by Chris Verlinde | Feb 28, 2020

What’s the big deal about seagrasses?

Seagrass meadows are made up of plants that live under water in our local estuaries. Just like the grass and plants in our yards where many types of insects, worms and small animals live, seagrass meadows provide habitat for many types of young fish and invertebrates, such as crabs and shrimp.

Between 70 and 90% of fish, crabs and shrimp that recreational and commercial fishermen catch, spend some time during their life in seagrass beds. In 2014, the commercial fishing industry contributed nearly $140 million, while recreational fishing spending contributed $6 billion to Florida’s Economy. If we did not have healthy seagrasses, we would not have this economic impact on our coastal economies (http://gulffishinfo.org/Gulf-Fisheries-Economics).

In addition:

· As seagrass blades move with the currents and tides, sediments are removed from the water, which contributes to improved water clarity.

· Seagrasses are the same type of plants that grow on land, they produce oxygen for marine life.

· Seagrasses filter excess nutrients from the water.

· Provide food and shelter for juvenile fish, shrimp and crabs.

· Endangered species such as manatees and green sea turtles depend on seagrass beds for food.

· Migratory birds depend on seagrass beds for foraging needs.

What can you do to help protect seagrasses?

While boating:

• Avoid seagrass beds. If you do run aground in a seagrass bed, turn off your engine, tilt up the engine and walk or pole your boat out of the shallow water.

• Be safe and know water depths and locations of seagrass beds by studying navigational charts.

• Seagrasses are usually found in shallow water and appear as dark spots or patches. Wear polarized sunglasses (to reduce glare) to help locate these areas.

• Always choose to use a pump-out station for your marine sanitation device.

• Stay in marked channels.

At home:

• To reduce pollution from entering our waterways, keep a buffer of native plants along your shoreline. This will also help to protect your property from erosion and slow flood waters during storm events.

• To save money, plant native plants that don’t require a lot of fertilizers and pesticides. Avoid seagrass beds when planning for dredging activities or pier construction.

• Comply with Shoreline Protection construction codes

• Maintain septic tanks.

In your community:

• Families and children can get out and snorkel these areas! Many sites are easy to access from public parks.

• Get involved with local organizations that promote nature protection.

• Working together, we can share with community members what we have learned about seagrasses at the 20th annual Seagrass Awareness Celebration, March 6, 2020 from noon until 4 pm at Shoreline Park South in Gulf Breeze Fl.

• Don’t litter!

The scarring of seagrass but a propeller.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 5, 2020

This is one of the most beloved animals on the planet… sea turtles. Discussions and debates over all sorts of local issues occur but when sea turtles enter the discussion, most agree – “we like sea turtles”, “we have nothing against sea turtles”. There are nonprofit groups, professional hospitals, and special rescue centers, devoted to helping them. I think everyone would agree, seeing one swimming near the shore, or nesting, is one of the most exciting things they will ever see. For folks visiting our beaches, seeing the white sand and emerald green waters is amazing, but it takes their visit to a whole other level if they encounter a sea turtle.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

They are one of the older members of the living reptiles dating back 150 million years. Not only are they one of the largest members of the reptile group, they are some of the largest marine animals we encounter in the Gulf of Mexico.

There are five species of marine turtles in the Gulf represented by two families. The largest of them all is the giant leatherbacks (Dermochelys coriacea). This beast can reach 1000 pounds and have a carapace length of six feet. Their shell resembles a leatherjacket and does not have scales. Because of their large size, they can tolerate colder temperatures than other marine turtles and found all over the globe. They feed almost exclusively on jellyfish and often entangled in open ocean longlines. There is a problem distinguishing clear plastic bags from jellyfish and many are found dead on beaches after ingesting them. Like all sea turtles, they approach land during the summer evenings to lay their eggs above the high tide line. The eggs incubate within the nest for 65-75 days and sex determination is based on the temperature of the incubating eggs; warmer eggs producing females. Also, like other marine turtles, the hatchlings can be disoriented by artificial lighting or become trapped in human debris, or unnatural holes, on the beach. These animals are known to nest in Florida and they are currently listed as federally endangered and are completely protected.

The large head of a loggerhead sea turtle.

Photo: UF IFAS

The other four species are found in the Family Chelonidae and have the characteristic scaled carapace. Much smaller than the leatherback, these are still big animals. The most common are the loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta). As the name suggest, the head of this sea turtle is quite large. Their carapace can reach lengths of four feet and they can weigh up to 450 pounds. The head usually has four scutes between the eyes and three scutes along the bridge connecting the carapace to the plastron. This animal prefers to feed on a variety of invertebrates from clams, to crabs, to even horseshoe crabs. It too is an evening nester and the young have similar problems as the leatherback hatchlings. The tracks of the nesting turtle can be identified by the alternating pattern made by the flippers. One flipper first, then the next. The loggerhead is currently listed as a federally threatened species.

A green sea turtle on a Florida beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

The green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas) is called so not for the color of its shell, but for the color of its internal body fat. They are fans of eating seagrasses, particularly “turtle grass” and other plants, which produce the green coloration of the fat. The fat is used to produce a world favorite, “turtle soup”, and has been a problem for the conservation of this species in some parts of the world. At one time, most green turtles nested in south Florida, but each year the number nesting in the north has increased. They can be distinguished from the loggerhead in that (1) their head is not as big, (2) there are only two scales between the eyes, and (3) their flipper pattern in sand is not alternating; green turtles throw both flippers forward at the same time. Green turtles are listed as federally threatened.

A hawksbill sea turtle resting on a coral reef in the Florida Keys.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The hawksbill turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata) is more tropical in distribution. They are a bit smaller, with a carapace length of three feet and a weight of 187 pounds, but their diet of sponges is another reason you do not find them often in the northern Gulf of Mexico. To feed on these, they have a “hawks-bill” designed to rip the sponges from their anchorages. Their shell is gorgeous and prized in the jewelry trade. “Tortoise-shell” glasses and earrings are very popular.

The most endangered of them all is the small Kemp’s Ridley sea turtle (Lepidochelys kempii). This little guy has a carapace length of a little over two feet and weighs in at no more than 100 pounds. These guys are commonly seen in the Big Bend area of Florida but for years no one knew where they nested. That was until 1947 when an engineer from Mexico found them nesting in large numbers (up to 40,000) at one time, in broad daylight in Rancho Nuevo, Mexico. This was problematic for the turtle because the locals would wait for the nesting to be complete before they would take the females and the eggs. Protected today they now face the problem that their migratory path across the Gulf takes them through Texas and Louisiana shrimping grounds, and through the 2010 Deep Water Horizon oil spill field. Not to mention that illegal poaching still occurs. Though all species of sea turtles have had problem with shrimp trawls, the Kemps had a particular problem, which led to the develop of the now required Turtle Excluder Device (T.E.D.S) found on shrimp trawls in the U.S. today. Sea turtles have strong site fidelity for nesting and in the 1980s many Kemp’s Ridley eggs were re-located to beaches in Texas in hopes to move the nesting to other locations. The program had some success and they have been reported to nest in Florida. Their diet consists primarily of crabs but there have been reports of them removing bait from fishing lines fishing from piers over the Gulf. This is species is federally endangered and is considered by many to be the most endangered sea turtle species on the planet.

Turtle friendly lighting.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Sea turtles face numerous human-caused problems including (1) artificial lighting that disorient hatchlings and cause mortality to 50% (or more) of the hatchlings, (2) items left on beaches (such as chairs, tents, etc.) that can impede adults and entrap hatchlings, (3) large holes dug on beaches in which hatchlings fall and cannot get out, (4) marine debris (such as plastics) which they confuse with prey and swallow, (5) boat strikes, sea turtles must surface to breath and can become easy targets, and (6) discarded fishing gear, in which they can become entangled and drown. These are simple things we can correct and protect these amazing Florida turtles.

References

Buhlmann, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 252.

Florida’s Endangered and Threatened Species. 2018. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/media/1945/threatend-endangered-species.pdf,

Species of Sea Turtle Found in Florida. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/sea-turtles/florida/species/.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.

to show you support bird conservation, please send an email to: chrismv@ufl.edu, Please put “chick magnet” in the subject line. Please allow 2 weeks to receive your magnet in the mail. Limited quantities available.