by Rick O'Connor | Oct 25, 2024

In the first article of this series, we discussed whether viruses were truly living organisms. Well, bacteria truly are. They possess all eight characteristics of life but differ from other forms of life in that they lack a true nucleus. Their genetic material just exists in the cytoplasm. This difference is large enough to place them in their own kingdom – Monera.

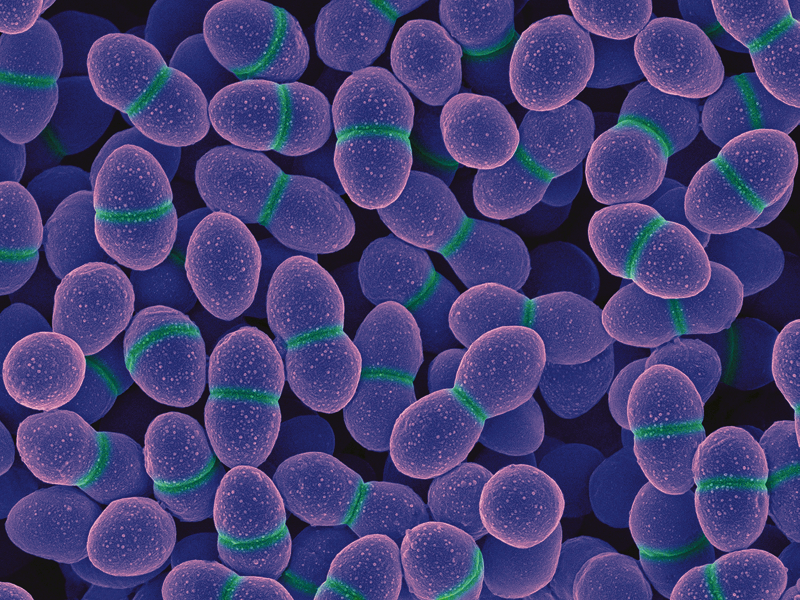

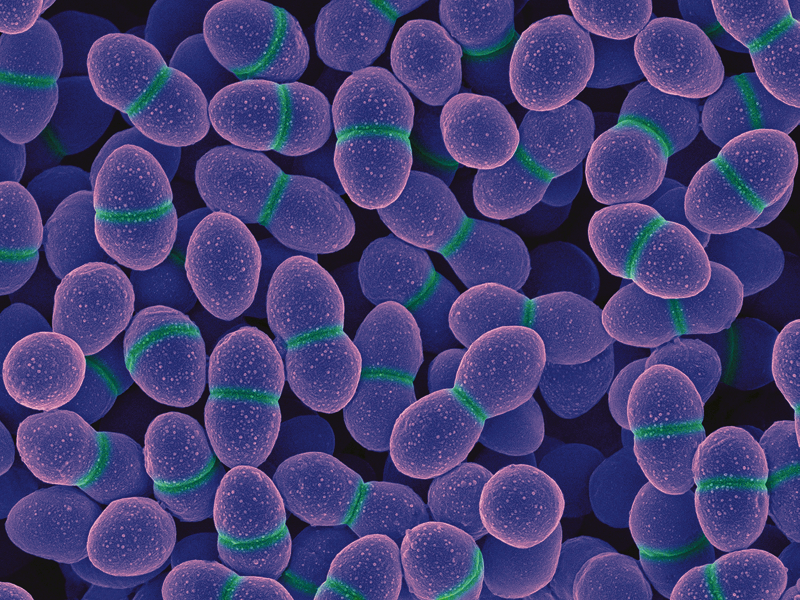

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

Bacteria are single celled creatures, though some “hook” together to form long chains. A single cell will average between 5-10 microns in size. This is much larger than a virus but smaller than many eukaryotic cells (those that possess a nucleus).

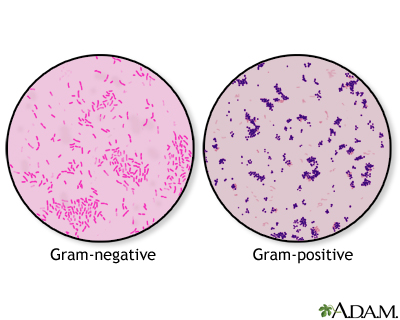

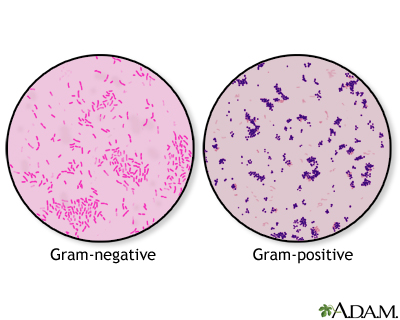

To further classify bacteria microbiologists will conduct a gram-stain test. Placing a cultured sample of bacteria on a slide, you “bath” them in what is called Gram-stain. Under the microscope the bacteria that appear “pink” are called gram negative, those that appear “purple” are gram positive. Thus, all bacteria can be quickly grouped into those that are gram negative and those that are gram positive.

After staining, gram negative bacteria appear pink in color; gram positive are purple.

Image: University of Florida

The next level of classification focuses on the shape of their cells. Those that are “rod-shaped” are called bacillus and often have the term in their name – such as Lactobacillus the bacteria found in milk that makes milk smell sour as their populations grow. The “sphere-shaped” bacteria are called coccus – such as Streptococcus (the bacterium that causes strep throat) and Enterococcus (the fecal bacterium used for monitoring water quality in marine waters). And the third group are “spiral-shaped” and are called spirillum – such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter both are human pathogens.

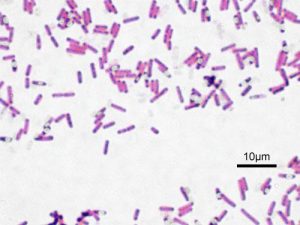

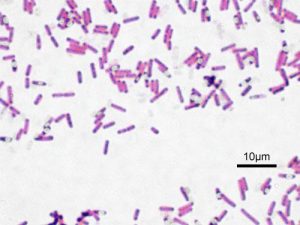

The rod-shaped bacterium known as bacillus.

Image: Wikipedia.

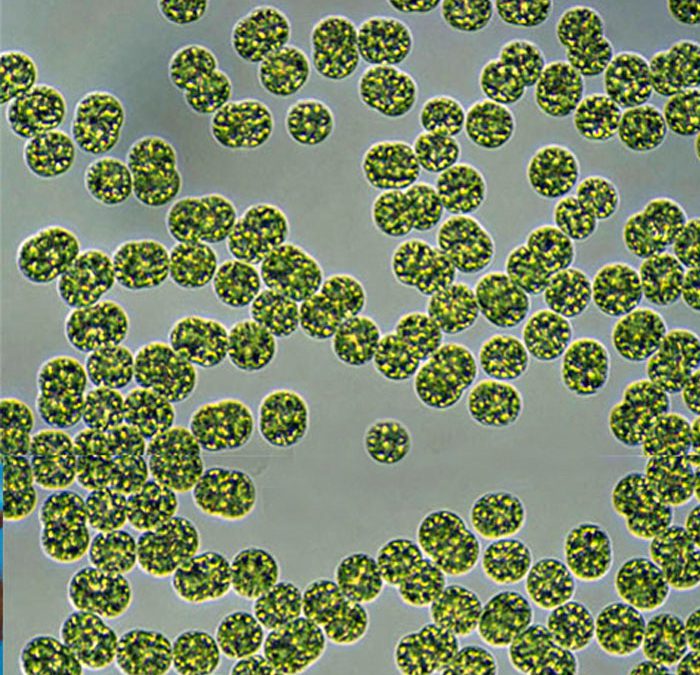

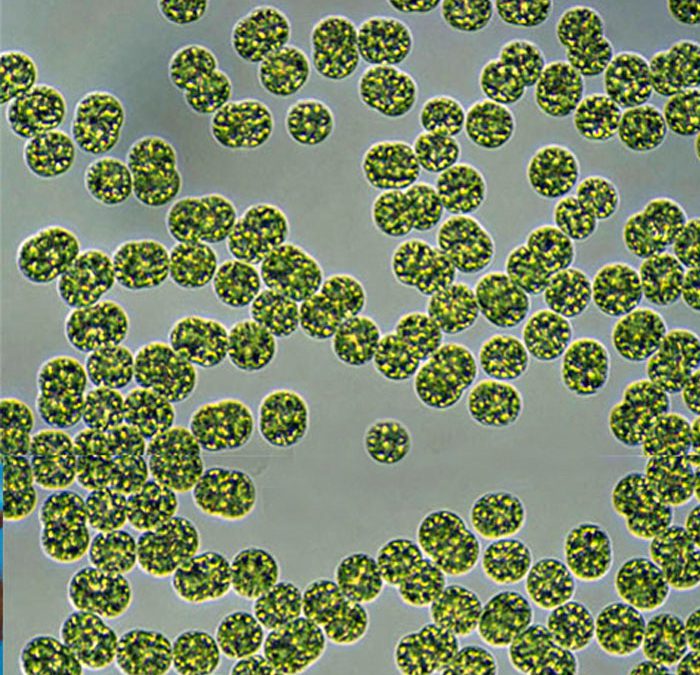

The bacterium known as coccus.

Image: Loyola University

The bacterium known as spirillum.

Image: Lake Superior College.

Bacteria are very abundant in the marine and estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They can be found floating in the water column, on the surface of the sediment, beneath the surface of the sediment, and on the bodies of marine organisms. When we think of bacteria we think of “dirty” conditions and disease, but many bacteria provide very important ecological benefits to the marine ecosystem and are “good” members of the community.

One important role some bacteria play is the conversion (“fixing”) of nutrients. Animals release toxic waste when they defecate and urinate. One of these is ammonia. Ammonia can bond with oxygen depleting the body of this needed element. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert toxic ammonia released into the environment into nitrite. Then another group of nitrogen fixing bacteria will convert nitrite into nitrate – a needed nutrient for plants, and eventually the entire food chain.

Some bacteria are excellent decomposers. When plants and animals die we say they “decay”. What is actually happening is the decomposing bacteria are converting nutrients in their bodies to forms that are usable by living organisms. One byproduct of this decomposition process is hydrogen sulfide – which smells like rotten eggs. In biologically productive ecosystems – like swamps and marshes – the smell of hydrogen sulfide is strong – often called “swamp gas”. It is the smell of nutrient conversion and much needed. Though in high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is toxic as well – there needs to be a balance. We see this same process happenings when we compost food waste to form fertilizers for our gardens.

One place where the smell of sulfur is very strong is near volcanic vents. If you have been to Yellowstone, or a volcano, the smell is very evident. There are what are termed “extreme bacteria” who can live in these very hot, almost toxic, environments. Just as plants take water and carbon dioxide and convert this to sugar in the process of photosynthesis, bacteria can convert toxic forms of sulfur into usable carbohydrates for other living organisms. In the 1970s marine scientists discovered thermal vents on the bottom of the ocean. These hot “chimneys” spew black clouds of smoke into the water column. Approaching these chimneys carefully they found water temperatures between 700-800°F! Living close to these chimneys they found communities of worms, shrimps, fish, and crabs. The walls of the chimneys are actually composed of sulfur fixing bacteria that are converting volcanic minerals and compounds into sugars in a process called chemosynthesis – which supports these deep-sea communities.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Of course, there are more familiar forms of bacteria that cause disease. Called pathogens – they can be problems for all marine life and sometimes humans. Fecal bacteria associated with human waste are not toxic in themselves at low concentrations. However, if their numbers increase (due to a sewage spill, etc.) these, and other possible pathogenic human bacteria, can be a human health issue. The Florida Department of Health monitors the fecal bacteria levels weekly at beaches where humans like to swim. High concentrations will require the department to issue health advisories. We know that all sorts of bacteria begin to replicate quickly in warmer conditions. This can be a problem with seafood that is not kept cold enough before serving. There are federal regulations on what temperatures commercially harvested seafood must be kept in order to be served or sold to the public. Federal and state agencies can monitor the temperatures of stored seafood as it moves from the fishing vessel to the table. But they cannot monitor it from your fishing rod to your table – that responsibility will fall on you. Pathogenic bacteria is the primary reason we refrigerate and/or freeze much of our food.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though bacteria in general have a bad name, many species are not harmful to us and are a major player in the health of our estuarine and marine communities.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 18, 2024

We are going to begin this series of articles with a “creature” that some do not consider alive – viruses. While studying marine science in college, and my early days as a marine science educator, there was a debate as to whether viruses were actually alive and should be included in a biology course. A quick glance at the textbooks of the time shows they were often omitted – though they were included in my microbiology class. Why were they omitted? Why did some consider them “non-living creatures”?

The coronavirus next to a strand of DNA.

Image: Florida International University.

Well, we always began biology 101 with the characteristics of life. Let’s scan these characteristics and see where viruses fit.

- Made of cells. This is not the case for viruses. A typical cell will include a cell membrane filled with cytoplasm and a nucleus, which is filled with genetic material (chromosomes containing DNA and RNA). An examination of a virus you will find it is either DNA or RNA encapsulated in a protein coat. It is “nucleus-like” in nature. Most cells run between 10-20 microns in size. A typical nucleus within a mammal cell will run between 5-10 microns. A typical virus would be 0.1 microns – these are tiny things – MUCH smaller than a cell.

- Process energy. Nope – they do not. Most cells utilize energy during their metabolism. Viruses do not do this.

- Growth and development. Nope again. They “spread”, which we discuss in a moment, but they do not grow. We are now 0-3.

- Homeostasis. Homeostasis is the movement of material and environmental control to remain stable – and viruses do not do this.

- Respond to stimuli. Yes… here is one they do. Studies show that viruses do respond to their chemical and physical environment.

- Metabolism. As mentioned above, this would be a no.

- Adaptation. Studies show that through very rapid reproduction they can adapt to the changing environment they are in.

- Reproduce. This is a sort of “yes/no” answer. They do reproduce (as we say – “spread”) but they do not do this on their own. They invade the nucleus within the cells of their host and replace their genetic material with that of the host creature. Then, during cell replication within the host, new viruses are produced and “spread”.

So, you can see why there is a debate. Of the eight common characteristics of life, viruses possess only three – and one of those can only be achieved with the assistance of a host creature. Now the question would be – do be labeled as a “creature” do you need ALL eight characteristics of life? Or only a few? And if only a few – how many? Because of this most biologists do not consider them alive.

During one class when we were discussing this a student made a comment – “don’t we KILL viruses? If so, then it must be alive first”. Point taken – and we should understand the phrase “kill a viruses” does not mean literally killing. It is a phrase we use. Though some argue we do kill viruses and thus…

Another point we could make here is that all life on the planet has been classified using a system developed by the Swedish botanist Carlos Linnaeus. Each creature is placed in a kingdom, then phylum, class, order, family, genus, and eventually a species name is given. We “name” the creature using its genus and species name – Homo sapiens for example. We do not see this for viruses.

All that said, both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Health indicate the “most common form of life in the sea are viral-like particles” – with over 10 million in a single drop of seawater. We will leave the debate here. Your thoughts?

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 4, 2024

Coastal wetlands are some of the most ecologically productive environments on Earth. They support diverse plant and animal species, provide essential ecosystem services such as stormwater filtration, and act as buffers against storms. As Helene showed the Big Bend area, storm surge is devastating to these delicate ecosystems.

Hurricane Track on Wednesday evening.

As the force of rushing water erodes soil, uproots vegetation, and reshapes the landscape, critical habitats for wildlife, in and out of the water, is lost, sometimes, forever. Saltwater is forced into the freshwater wetlands. Many plants and aquatic animal species are not adapted to high salinity, and will die off. The ecosystem’s species composition can completely change in just a few short hours.

Prolonged storm surge can overwhelm even the very salt tolerant species. While wetlands are naturally adept at absorbing excess water, the salinity concentration change can lead to complete changes in soil chemistry, sediment build-up, and water oxygen levels. The biodiversity of plant and animal species will change in favor of marine species, versus freshwater species.

Coastal communities impacted by a hurricane change the view of the landscape for months, or even, years. Construction can replace many of the structures lost. Rebuilding wetlands can take hundreds of years. In the meantime, these developments remain even more vulnerable to the effects of the next storm. Apalachicola and Cedar Key are examples of the impacts of storm surge on coastal wetlands. Helene will do even more damage.

Many of the coastal cities in the Big Bend have been implementing mitigation strategies to reduce the damage. Extension agents throughout the area have utilized integrated approaches that combine natural and engineered solutions. Green Stormwater Infrastructure techniques and Living Shorelines are just two approaches being taken.

So, as we all wish them a speedy recovery, take some time to educate yourself on what could be done in all of our Panhandle coastal communities to protect our fragile wetland ecosystems. For more information go to:

https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fflifasufledu/docs/gsi-documents/GSI-Maintenance-Manual.pdf

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2023/11/29/cedar-key-living-shorelines/

by Laura Tiu | Sep 13, 2024

Western Dune Lake Tour

Walton County in the Florida Panhandle has 26 miles of coastline dotted with 15 named coastal dune lakes. Coastal dune lakes are technically permanent bodies of water found within 2 miles of the coast. However, the Walton County dune lakes are a unique geographical feature found only in Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Oregon, and here in Walton County.

What makes these lakes unique is that they have an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico through an outfall where Gulf water and freshwater flow back and forth depending on rainfall, storm surge and tides. This causes the water salinity of the lakes to vary significantly from fresh to saline depending on which way the water is flowing. This diverse and distinctive environment hosts many plants and animals unique to this habitat.

There are several ways to enjoy our Coastal Dune Lakes for recreation. Activities include stand up paddle boarding, kayaking, or canoeing on the lakes located in State Parks. The lakes are popular birding and fishing spots and some offer nearby hiking trails.

The state park provides kayaks for exploring the dune lake at Topsail. It can be reached by hiking or a tram they provide.

Walton County has a county-led program to protect our coastal dune lakes. The Coastal Dune Lakes Advisory Board meets to discuss the county’s efforts to preserve the lakes and publicize the unique biological systems the lakes provide. Each year they sponsor events during October, Dune Lake Awareness month. This year, the Walton County Extension Office is hosting a Dune Lake Tour on October 17th. Registration will be available on Eventbrite starting September 17th. You can check out the Walton County Extension Facebook page for additional information.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 30, 2024

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast as well. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

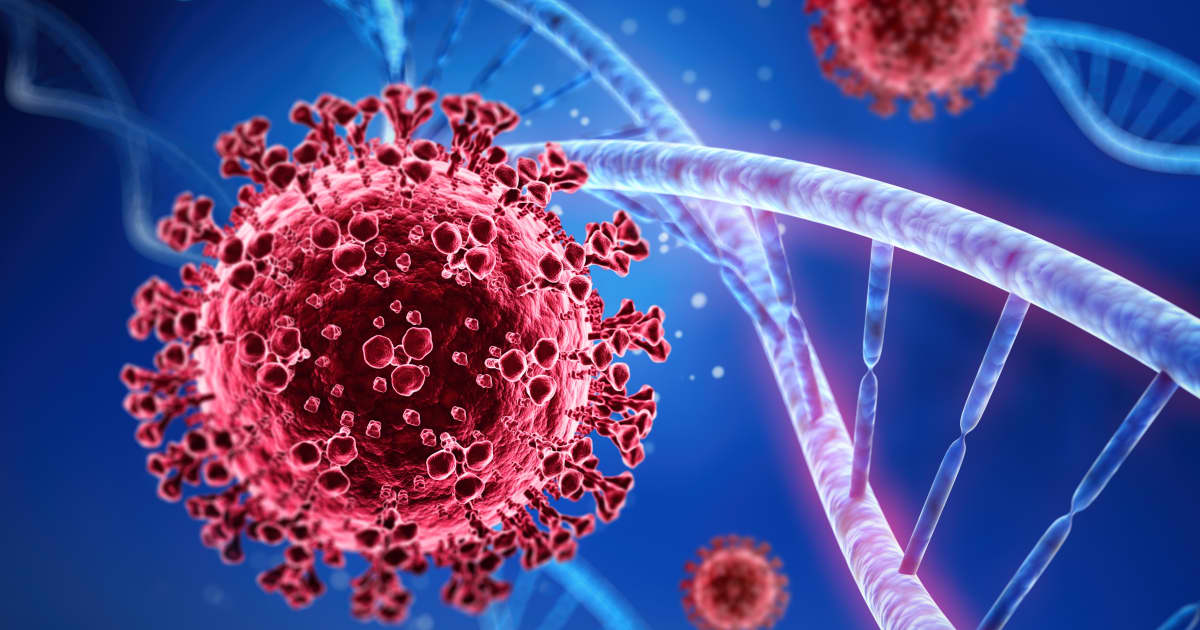

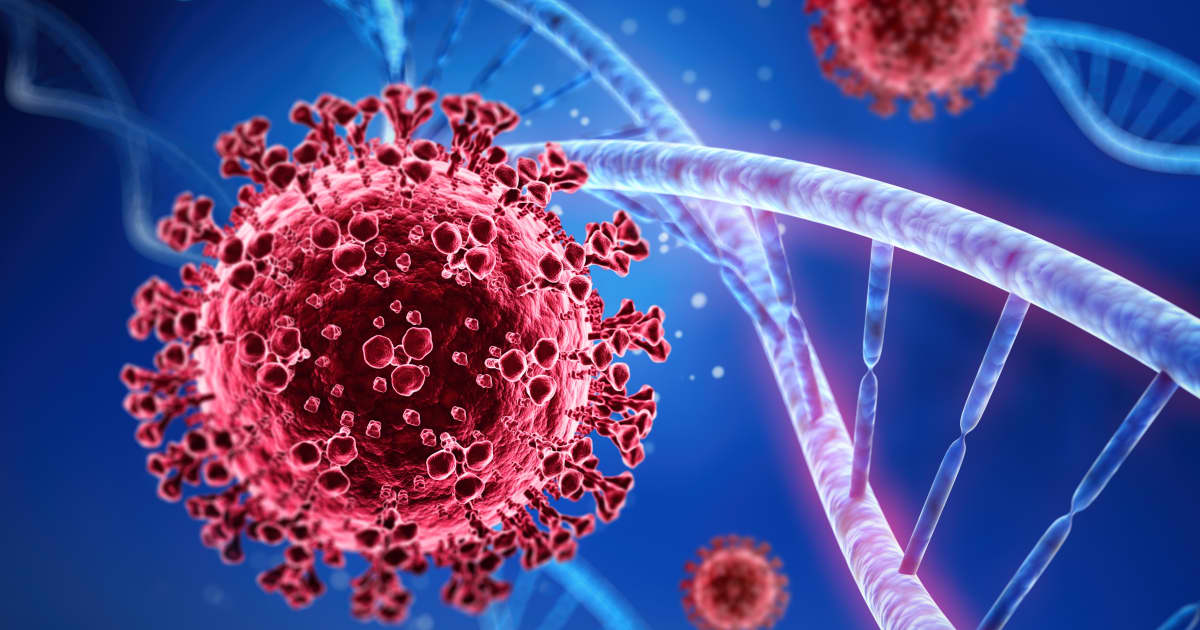

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2024 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

2024 Results

A record 168 volunteers surveyed 15 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (23%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 152 transects (15,200m2) were surveyed logging 133 scallops. An additional 50 scallops were found outside the official transect for a total of 183 scallops for 2024.

2024 Big Lagoon Results

75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids (64%) within the Big Lagoon. 67 transects were conducted covering 6,700m2.

101 scallops were logged with an additional 42 found outside the official transects. This equates to 3.02 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs and conchs, both scallop predators, as well as some sea urchins. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in six of the seven grids (86%) but was never abundant.

2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

93 volunteers surveyed 8 of the 55 grids (14%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 85 transects were conducted covering 8,500m2.

32 scallops were logged with an additional 8 found outside the official transects. This equates to 0.76 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and sand dollars. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in five of the eight grids (62%) and was abundant in grids surveyed on the eastern end of the survey area.

2015 – 2024 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

323 |

104 |

0.64 |

2015 – 2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

1731 |

36 |

0.42 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. However, you will notice that in 2024 the population in Big Lagoon moved from collapsed to vulnerable for this year alone.

There are some possible explanations for this.

- The survey effort in Big Lagoon was stronger than Santa Rosa Sound. 75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids. This equates to 11 volunteers / grid surveyed and 64% of the survey area was covered. With Santa Rosa Sound there were 93 volunteers who surveyed 8 of the 55 grids. This equates to 12 volunteers / grid surveyed but only 14% of the survey area was covered. Most of the SRS grids surveyed were in the Gulf Breeze/Pensacola Beach area. More effort east of Big Sabine may yield more scallops found.

- There is the possibility of different teams counting the same scallops. Each grid is 1-nautical mile, so the probability of one team laying their transect over an area another team did is low, but not zero.

- It is known that scallops have periodic population booms. Our search this year may have witnessed this. We will know if encounters significantly decrease in 2025.

Whether there was double counting this year or not, the frequency of encounter was much higher than in previous years. There were multiple reports from the public on social media about scallop encounters as well, and in some places we did not survey. It is also understood that scallops mass spawn. So, high density populations are required for reproductive success. The “boom” we witnessed this year suggests that there is a population of scallops – albeit a collapsed one – in our bay. It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 168 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Harbor Amiss Glen Grant Eric Stone

David Anderson Phil Harter Neil Tucker

Laura Baker Gina Hertz Christian Wagley

Melinda Bennett Sean Hickey Jaden Wielhouwer

Samantha Bergeron (USM class) John Imhof Keith Wilkins

Cheri Bone Jason Mellos Christy Woodring

Cindi Cagle Greg Patterson

Cher Clary Kelly Rysula

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found. Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

Rick O’Connor Florida Sea Grant; Escambia County

Thomas Derbes II Florida Sea Grant; Santa Rosa County

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I bet that for most of you, this is not only a worm you have never seen – it is a worm you have never heard of before. I learned about them first in college, which was almost 50 years ago, and have never seen one. But, other than the earthworm, the world of worms is basically hidden from us.

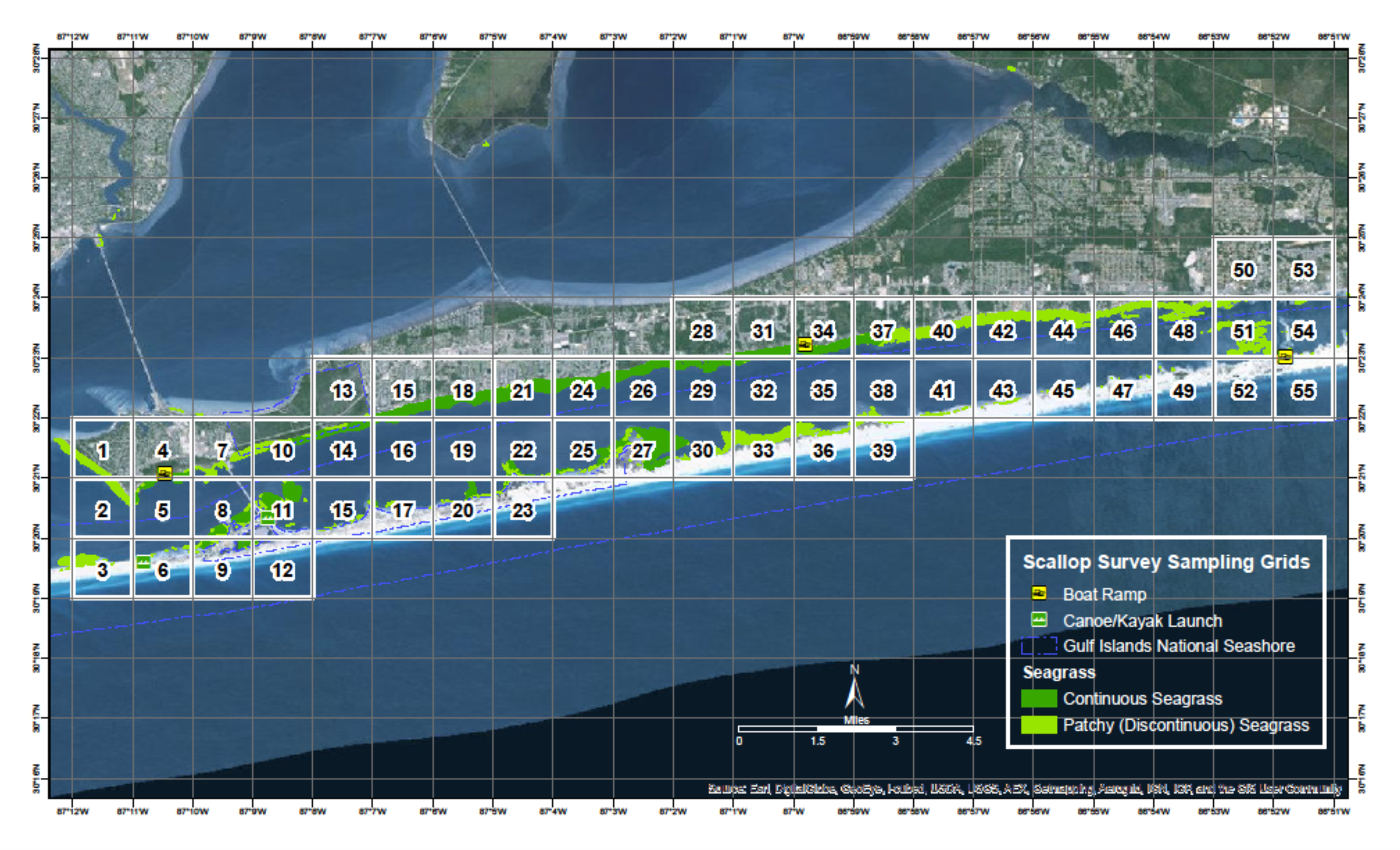

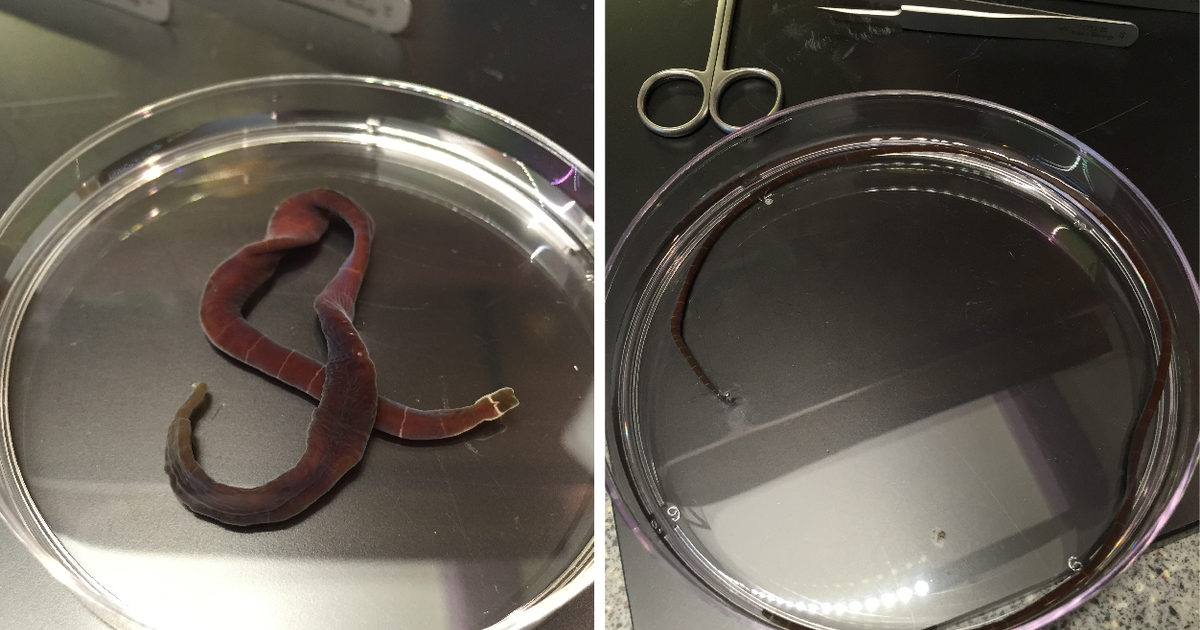

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

Nemerteans are a group of about 1300 species in the Phylum Nemertea and are often called ribbon or proboscis worms. They do possess a proboscis used to capture prey. Most are marine and live on the bottom both near the beach and a great depth. They are more temperate than tropical and do have a few parasitic forms.

Adult Nemertea Worms – Terra C. Hiebert, PhD, Oregon University

In appearance they resemble flatworms but are larger and more elongated. Most are less than 20cm (8in) but some species along the Atlantic coast can reach 2m (7ft). The head end can be lobed or even spatula looking. Some species are pale in color and others quite colorful. Most nemerteans move over the substrate on a trail of slime produced by their skin. Some species can swim.

As mentioned, the proboscis is used to capture prey. It is a tube-like structure held in a sac near the head. When prey is detected, they can launch the proboscis out and over the victim. Sticky secretions help hold on to the prey while they ingest. Many species are armed with a stylet, dart, that is attached to the proboscis and is driven into the prey like a spear. From there toxins, secreted from the base of the proboscis are injected into the prey.

For many species the proboscis is connected to the digestive tract via a tube, there is no true mouth, but they do possess an anus. They are all carnivorous and feed on a variety of small living and dead invertebrates. Their menu includes annelid worms, mollusk, and crustaceans.

Nemerteans do possess a brain and most find their prey using chemoreception, though some species must literally bump into their prey to find it. They have multiple eyes that can detect light, and, like the true flatworms, they are negatively phototaxic. They are nocturnal by habitat and is probably why most of us have never seen one.

Many nemerteans, particularly the larger ones, have a habit of fragmenting when irritated, creating new worms. Most species have separate sexes and fertilization of the gametes is external (fertilization occurs in the environment).

Nemerteans are an interesting group of semi-large, sometimes toxic, hunters who prowl through the marine waters at night hunting prey. Seen by few, maybe one evening, while exploring or floundering, you may see one.

In Part 3 we will begin to explore a group of worms that are more round than flat. The Gastrotrichs.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.