by Sheila Dunning | Jul 23, 2018

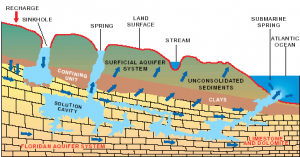

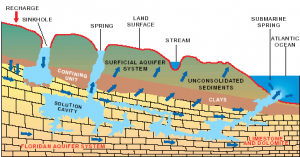

Hydrologic cycle and geologic cross-section image courtesy of Florida Geological Survey Bulletin 31, updated 1984.

With more than 250 crystal clear springs in Northwest Florida it is just a short road trip to a pristine swimming hole! Springs and their associated flowing water bodies provide important habitat for wildlife and plants. Just as importantly, springs provide people with recreational activities and the opportunity to connect with the natural environment. While paddling your kayak, floating in your tube, or just wading in the cool water, think about the majesty of the springs. They are the visible part of the Florida Aquifer, the below ground source of most Florida’s drinking water.

A spring is a natural opening in the Earth where water emerges from the aquifer to the soil surface. The groundwater is under pressure and flows upward to an opening referred to as a spring vent. Once on the surface, the water contributes to the flow of rivers or other waterbodies. Springs range in size from small seeps to massive pools. Each can be measured by their daily gallon output which is classified as a magnitude. First magnitude springs discharge more than 64.6 million gallons of water each day. Florida has over 30 first magnitude springs. Four of them can be found in the Panhandle – Wakulla Springs and the Gainer Springs Group of 3.

Wakulla Springs is located within Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. The spring vent is located beneath a limestone ledge nearly 180 feet below the land surface. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have utilized the area for nearly 15,000 years. Native Americans referred to the area as “wakulla” meaning “river of the crying bird”. Wakulla was the home of the Limpkin, a rare wading bird with an odd call.

Over 1,000 years ago, Native Americans used another first magnitude spring, the Gainer Springs group that flow into the Econfina River. “Econfina”, or “natural bridge” in the local native language, got its name from a limestone arch that crossed the creek at the mouth of the spring. General Andrew Jackson and his Army reportedly used the natural bridge on their way west exploring North America. In 1821, one of Jackson’s surveyors, William Gainer, returned to the area and established a homestead. Hence, the naming of the waters as Gainer Springs.

Three major springs flow at 124.6 million gallons of water per day from Gainer Springs Group, some of which is bottled by Culligan Water today. Most of the springs along the Econfina maintain a temperature of 70-71°F year-round. If you are in search of something cooler, you may want to try Ponce de Leon Springs or Morrison Springs which flows between 6.46 and 64.6 million gallons a day. They both stay around 67.8°F. Springs are very cool, clear water with such an importance to all living thing; needing appreciation and protection.

by Chris Verlinde | Jun 23, 2018

As the heat indicies rise, there a number of organizations that offer great learning experiences about our local Natural Resources!! While it is great to have the outdoor hands-on learning, the afternoon heat can feel suffocating. Here are a couple of nature centers that you can visit to get out of the heat.

Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve is home to the Reserve’s Nature Center, located at 108 Island Drive, in East Point Florida. Inside the air-conditioned Nature Center are many interactive displays and tanks with live local animals. At one end of the center, there is a large mural that takes you from the upper-parts of the Apalachicola River to the Gulf of Mexico, There are many native animals identified on the mural. There is an area with plenty of artifacts to keep the young and old naturalist busy.

are many interactive displays and tanks with live local animals. At one end of the center, there is a large mural that takes you from the upper-parts of the Apalachicola River to the Gulf of Mexico, There are many native animals identified on the mural. There is an area with plenty of artifacts to keep the young and old naturalist busy.

The interactive cultural displays are really interesting and provide much information about the fishing industry that Apalachicola is known for throughout Florida.

The Reserve features a many trails that lead throughout the property and many to the water. The Apalachicola National Estuary Reserve is one of 29 National Estuarine Research Reserves in the U.S. Each reserve is protected for “long-term research, water quality and habitat monitoring, education, and coastal stewardship.”

The Reserve is open to the public Tuesday through Saturday from 9 am until 4 pm, admission is free.

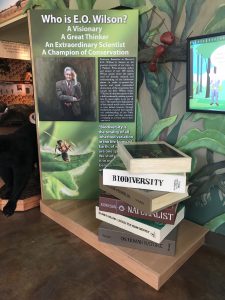

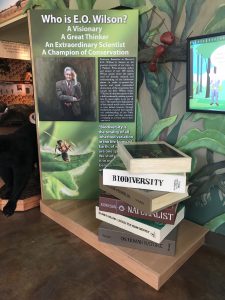

Photos provided by Chris Verlinde Heading to the west, near the town of Freeport Florida, you will find the E.O. Wilson Biophilia Nature Center. This amazing place will keep you and your family entertained for hours. If you plan to go, the center is only open to the public on Thursday and Friday during June and July from 9 am until 2 pm. The cost is $8.00 for adults, $5.00 for children ages 3-12 and free for those 2 and under. The rest of the year, the staff are dedicated to teaching local students from surrounding school districts about biodiversity in Northwest Florida. As you enter the exhibit building there is a tribute to the famous naturalist E.O Wilson, whose work is the inspiration for center. Dr. Wilson is dedicated to teaching others about the importance of conservation of biodiversity. He coined the term “biophilia” which means “the love of all living things.” The exhibit hall features many different displays on the cultural and natural resources in the area. The center features a reptile room, classrooms, an amphitheater, porches to enjoy your lunch and the “World of Wonder Exhibit.” which is a Science on a Sphere – a giant globe that utilizes technology to teach about the planets, our weather, and more.

Heading to the west, near the town of Freeport Florida, you will find the E.O. Wilson Biophilia Nature Center. This amazing place will keep you and your family entertained for hours. If you plan to go, the center is only open to the public on Thursday and Friday during June and July from 9 am until 2 pm. The cost is $8.00 for adults, $5.00 for children ages 3-12 and free for those 2 and under. The rest of the year, the staff are dedicated to teaching local students from surrounding school districts about biodiversity in Northwest Florida. As you enter the exhibit building there is a tribute to the famous naturalist E.O Wilson, whose work is the inspiration for center. Dr. Wilson is dedicated to teaching others about the importance of conservation of biodiversity. He coined the term “biophilia” which means “the love of all living things.” The exhibit hall features many different displays on the cultural and natural resources in the area. The center features a reptile room, classrooms, an amphitheater, porches to enjoy your lunch and the “World of Wonder Exhibit.” which is a Science on a Sphere – a giant globe that utilizes technology to teach about the planets, our weather, and more.

Animals that can be found at the center include: birds of prey, bobcats, turtles and snakes, a red-cockaded woodpecker, a fox, and chickens. A short walk outside, you will find an authentic cracker house (with snakes!) and an organic garden.

The E.O. Wilson Biophilia center is a wonderful place to visit, check it out soon!!

by Rick O'Connor | May 31, 2018

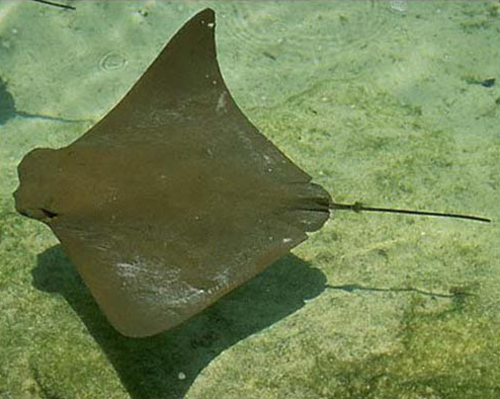

It is now late May and in recent weeks I, and several volunteers, have been surveying the area for terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring local seagrass beds. We see many creatures when we are out and about; one that has been quite common all over the bay has been the “stingray”.

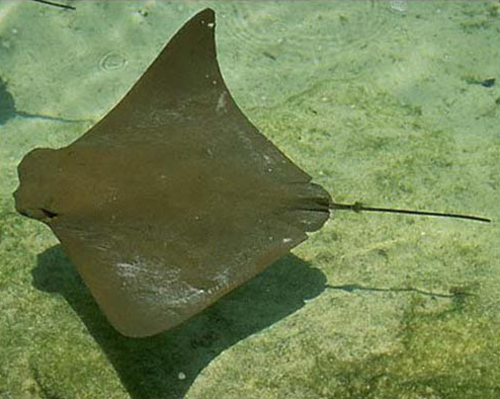

The cownose ray is often mistaken for the manta ray. It lacks the palps (“horns”) found on the manta.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

These are intimidating creatures… everyone knows how they can inflict a painful wound using the spine in their tail, but may are not aware that not all “stingrays” can actually use a spine to drive you off – actually, not all “rays” are “stingrays”.

So what is a ray?

First, they are fish – but differ from most fish in that they lack a bony skeleton. Rather it is cartilaginous, which makes them close cousins of the sharks.

So what is the difference between a shark and a ray?

You would immediately jump on the fact that rays are flat disked-shape fish, and that sharks are more tube-shaped and fish like. This is probably true in most cases, but not all. The characteristics that separate the two groups are

- The five gill slits of a shark are on the side of the head – they are on the ventral side (underside) of a ray

- The pectoral fin begins behind the gill slits in sharks, in front of for the ray group

Not all rays have the whip-like tail that possess a sharp spine; some in fact have a tube-shaped body with a well-developed caudal fin for a tail.

There are eight families and 19 species of rays found in the Gulf of Mexico. Some are not common, but others are very much so.

Sawfish are large tube-shaped rays with a well-developed caudal fin. They are easily recognized by their large rostrum possessing “teeth” giving them their common name. Walking the halls of Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola, you will see photos of fishermen posing next to monsters they have captured. Sawfish can reach lengths of 18 feet… truly intimidating. However, they are very slow and lethargic fish. They spend their lives in estuaries, rarely going deeper than 30 feet. They were easy targets for fishermen who displayed them as if they caught a true monster. Today they are difficult to find and are protected. There are still sightings in southwest Florida, and reports from our area, but I have never seen one here. I sure hope to one day. There are two species in the Gulf of Mexico.

Guitarfish are tube-shaped rays that are very elongated. They appear to be sharks, albeit their heads are pretty flat. They more common in the Gulf than the bay and, at times, will congregate near our reefs and fishing piers to breed. They are often confused with the electric rays called torpedo rays, but guitarfish lack the organs needed to deliver an electric shock. They have rounded teeth and prefer crustaceans and mollusk to fish. There is only one species in the Gulf.

Torpedo rays can deliver an electric shock – about 35 volts of one. Though there are stories of these shocking folks to death, I am not aware of any fatalities. Nonetheless, the shock can be serious and beach goers are warned to be cautious. I once mistook one buried in the sand for a shell. Let us just say the jolt got my attention and I may have had a few words for this fish before I returned to the beach. We have two species of torpedo rays in the Gulf of Mexico.

Skates look JUST like stingrays – but they lack the whip-like tail and the venomous spine that goes with it. They are very common in the inshore waters of the Florida Panhandle and though they lack the terrifying spine we are all concerned about, they do possess a series of small thorn-like spine on the back that can be painful to the bare foot of a swimmer. Skates are famous for producing the black egg case folks call the “mermaids’ purse”. These are often found dried up along the shore of both the Gulf and they bay and popular items to take home after a fun day at the beach. There are four species of skates found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Stingrays… this is the one… this is the one we are concerned about. Stingrays can be found on both sides of our barrier islands and like to hide beneath the sand to ambush their prey. More often than not, when we approach they detect this and leave. However, sometimes they will remain in the sand hoping not to be detected. The swimmer then steps on their backs forcing them to whip their long tail over and drive the serrated spine into your foot. This usually makes you move off them – among other things. The piercing is painful and spine (which is actually a modified tooth) possesses glands that contain a toxic substance. It really is no fun to be stung by these guys. Many people will do what is called the “stingray shuffle” as they move through the water. This is basically sliding your feet across the sand reducing your chance of stepping on one. They are no stranger to folks who visit St. Joe Bay. The spines being modified teeth can be easily replaced after lodging in your foot. Actually, it is not uncommon to find one with two or three spines in their tails ready to go. Stingrays do not produce “mermaids’ purses” but rather give live birth. There are five species in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Butterfly ray is a strange looking fish and easy to recognize. The wide pectoral fins and small tail gives it the appearance of a butterfly. Despite the small tail, it does possess a spine. However, the small tail makes it difficult for the butterfly ray to pierce you with it. There is only one species in the Gulf, the smooth butterfly ray.

Eagle rays are one of the few groups of rays that actually in the middle of the water column instead of sitting on the ocean floor. They can get quite large and often mistaken for manta rays. Eagle rays lack the palps (“horns”) that the manta ray possesses. Rather they have a blunt shaped head and feed on mollusk. They do have venomous spines but, as with the butterfly ray, their tails are too short to extend and use it the way stingrays do. There are two species. The eagle ray is brown and has spots all over its back. The cownose ray is very common and almost every time I see one, I hear “there go manta rays”… again, they are not mantas. They have a habit of swimming in the surf and literally body surfing. Surfers, beachcombers, and fishermen frequently see them.

Last but not least is the very large Manta ray. This large beast can reach 22 feet from wingtip to wing tip. Like eagle rays, they swim through the ocean rather than sit on the bottom. They have to large “horns” (called palps) that help funnel plankton into their mouths. These horns give them one of their common names – the devilfish. Mantas, like eagle and butterfly rays, do have whip-like tails and a venomous spine, but like the above, their tails are much shorter and so effective placement of the spine in your foot is difficult.

Many are concerned when they see rays – thinking that all can inflict a painful spine into your foot – but they are actually really neat animals, and many are very excited to see them.

References

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M. College Station, TX. pp. 327.

Shipp, R. L. 2012. Guide to Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. KME Seabooks. Mobile AL. pp. 250.

by Rick O'Connor | May 25, 2018

In recent weeks, volunteers and I have been surveying local estuaries counting terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring seagrass. One animal that has been very visible during these surveys is the relatively large snail known as the crown conch (Melongena corona). Its shell is often found with a striped hermit crab living within, but it is actually produced by a fleshy snail, who is a predator to those slow enough for it to catch.

The white spines along the whorl give this snail its common name – crown conch.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

The shell is familiar to most who venture to the estuary side of our beaches. Reaching around five inches in length, crown conch shells are spiral with a wide aperture (opening) and brown to purple to white in color. Each whorl ends with white spins giving it the appearance of a crown and – hence – it’s common name. They are typically seen cruising along the sediments near grassbeds, salt marshes and oyster reefs – their long black siphons extended drawing in seawater for oxygen, but also to detect scents that will lead them to food.

These snails breed from winter to early summer. Females, larger than males, will develop 15-500 eggs in capsules, which they attach to hard structures within the habitat; such as wood, seagrass blades, and shell material.

Crown conchs are subtropical species and have a low tolerance for cold water. They are common in the panhandle and may expand further north along the Atlantic coast if warming trends continue. They have a higher tolerance for changes in salinity and can tolerate salinity as low as 8 ppt. The salinities within Pensacola Bay can be as low as 10 ppt and Santa Rosa Sound / Big Lagoon are typically between 20-30 ppt. The developing young require higher salinities and thus breeding takes in the lower portions of our estuaries.

These are guys are snail predators – seeking prey slow enough for them to catch. Common targets include the bivalves such as oysters and clams, but they are known to seek out other snails – like whelks. Crown conchs are known to feed on dead organisms they encounter and may be cannibalistic. As with all creatures, they have their predators as well. The large thick shell protects them from most but other snails, such as whelks and murex, are known predators of the crown conch.

These conchs tend to stay closer to shallow water (less than 3 ft.) due the large number of predators at depth. They are common in seagrass meadows and salt marshes and – if in high numbers with few competitors – have been considered an indicator of poor water quality. There is no economic market for them but they are monitored due to the fact they affect the populations of commercially important oysters and clams.

The “snorkel” is called a siphon and is used by the snail to draw water into the mantle cavity. Here it can extract oxygen and detect the scent of prey.

Photo: Franklin County Extension

It is an interesting animal, a sort of “jaws” of the snail world, and a possible candidate for a citizen science water quality monitoring project. Enjoy exploring your coastal estuaries this summer and discover some of these interesting animals.

Reference

Masterson, J. 2008. Indian River Lagoon Species Inventory: Crown Conch Melongena corona. Smithsonian Marine Station at Ft. Pierce, Florida. http://www.sms.si.edu/irlspec/Melongena_corona.htm.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 14, 2018

Spring has sprung and it is time to get outside and explore this great Florida Panhandle area. In neighboring Santa Rosa County, a terrific destination for a variety of outdoor activities is Blackwater River State Park. Visitors can canoe, kayak, tube, fish and swim the river. Hikers can enjoy trails through nearly 600 acres of undisturbed natural communities. Bring a picnic and hang out at one of several pavilions or white sand beaches that dot the river (restroom facilities available). Near the pavilions, stop and see one of the largest and oldest Atlantic white cedars, recognized as a Florida Champion tree in 1982. The park also offers 30 campsites for tents and RVs. Park entry is $4.00 per car, payable at the ranger station or via the honor system (bring exact change, please).

The Blackwater River is considered one of the purest and pristine sand-bottom rivers in the world. The water is tea-colored from the tannins and organic matter that color the water as it weaves through the predominantly pine forest. The river is shallow with a beautiful white sandy bottom, a nice feature for those tubing or paddling the trail. The river flows for over 50 miles and is designated as a Florida canoe trail. Multiple small sand beach areas line the river and provide plenty of space to hang out, picnic, or throw a Frisbee. Blackwater eventually flows into Pensacola Bay and the Gulf of Mexico bringing high quality freshwater into this important estuary.

A favorite trail in the Park is the Chain of Lakes Nature Trail. Parking for this 1.75 mile loop trail is at South Bridge on Deaton Bridge Road. The trail head is well marked and has a boardwalk that leads into the floodplain forest. The trail winds through a chain of shallow oxbow lakes and swamp that dot the former route of the river. If you are lucky and it is a clear, blue-sky day, you may see a beautiful rainbow effect as the sun hits the water. We call this the pastel swamp rainbow effect. This is a result of the natural oils from the cypress cones settling on the surface of the water and associated trapped pollen.

The trail then turns to sneak through the sandhill community in the park with giant longleaf pines, wiregrass and turkey oak. Evidence of prescribed burning shows management efforts to maintain the forest. Cinnamon ferns, bamboo and other natives appear in pockets along the trail. The trail in this section is blanketed with a mosaic of exposed root systems, so be careful as you step. Finally, pack some bug spray and a water bottle for this fun hike.

For more information, visit the park page: https://www.floridastateparks.org/park/Blackwater-River

Sandhill pine forest at Blackwater River State Park

2737 – Chain of Lakes trailhead at Blackwater River State Park

“Rainbow Swamp” on the Chain of Lakes trail at Blackwater River State Park

Beautiful sandy beaches along the Blackwater River in the State Park.

by Sheila Dunning | Apr 14, 2018

Having just completed the Okaloosa/Walton Uplands Master Naturalist course, I would like to share information from the project that was presented by Ann Foley.

The Florida Torreya. Photo provided by Shelia Dunning

The Florida Torreya is the most endangered tree in North America, and perhaps the world! Less than 1% of the historical population survives. Unless something is done soon, it may disappear entirely! You can see them on public lands in Florida at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve and beautiful Torreya State Park.

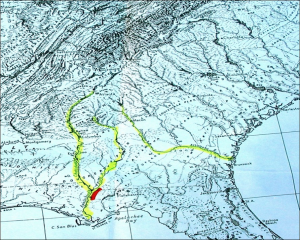

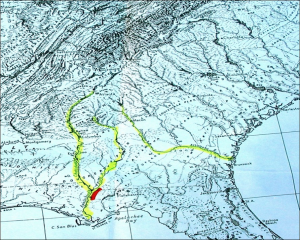

The Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the oldest known tree species on earth; 160 million years old. It was originally an Appalachian Mountains ranged tree. As a result of our last “Ice Age” melt, retreating Icebergs pushed ground from the Northern Hemisphere, bringing the Florida Torreya and many other northern plant species with them.

The Florida Torreya was “left behind” in its current native pocket refuge, a short 40 mile stretch along the banks of the Apalachicola River. There were estimates of 600,000 to 1,000,000 of these trees in the 1800’s. Torreya State Park, named for this special tree, is currently home to about 600 of them. Barely thriving, this tree prefers a shady habitat with dark, moist, sandy loam of limestone origin which the park has to offer.

Hardy Bryan Croom, Botanist, discovered the tree in 1833, along the bluffs and ravines of Jackson, Liberty and Gadsen Counties, Florida and Decatur County in Georgia. He named it Florida Torreya (TOR-ee-uh), in honor of Dr. John Torrey, a renowned 18th century scientist.

Torreya trees are evergreen conifers, conically shaped, have whorled branches and stiff, sharp pointed, dark green needle-like leaves. Scientists noted the Torreya’s decline as far back as the 1950’s! Mature tree heights were once noted at 60 feet, but today’s trees are immature specimens of 3-6 feet, thought to be ‘root/stump sprouts.’

Known locally as “Stinking Cedar,” due to its strong smell when the leaves and cones are crushed, it was used for fence posts, cabinets, roof shingles, Christmas trees and riverboat fuel. Over-harvesting in the past and natural processes are taking a tremendous toll. Fungi are attacking weakened trees, causing the critically endangered species to die-off. Other declining factors include: drought, habitat loss, deer and loss of reproductive capability.

With federal and state protection, the Florida Torreya was listed as an endangered species in 1983. There is great concern for this ancient tree in scientific community and with citizen organizations. Efforts are underway to help bring this tree back from the edge of extinction!

Efforts include CRISPR gene editing technology research being done by the University of Florida Dept. of Forest Resources and Conservation- making the tree more resistant to disease. Torreya Guardians “rewilding and “assisted migration”. Reintroducing the tree to it’s former native range in the north near the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC, which has maintained a grove of Torreya trees and offspring since 1939 and supplying seeds for propagation from their healthy forest. Long before saving the earth became a global concern, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel), spoke through his character the Lorax warning against urban progress and the danger it posed to the earth’s natural beauty. All of these groups, and many others, hope their efforts will collectively help bring this tree back from the brink!