by Rick O'Connor | Oct 25, 2024

In the first article of this series, we discussed whether viruses were truly living organisms. Well, bacteria truly are. They possess all eight characteristics of life but differ from other forms of life in that they lack a true nucleus. Their genetic material just exists in the cytoplasm. This difference is large enough to place them in their own kingdom – Monera.

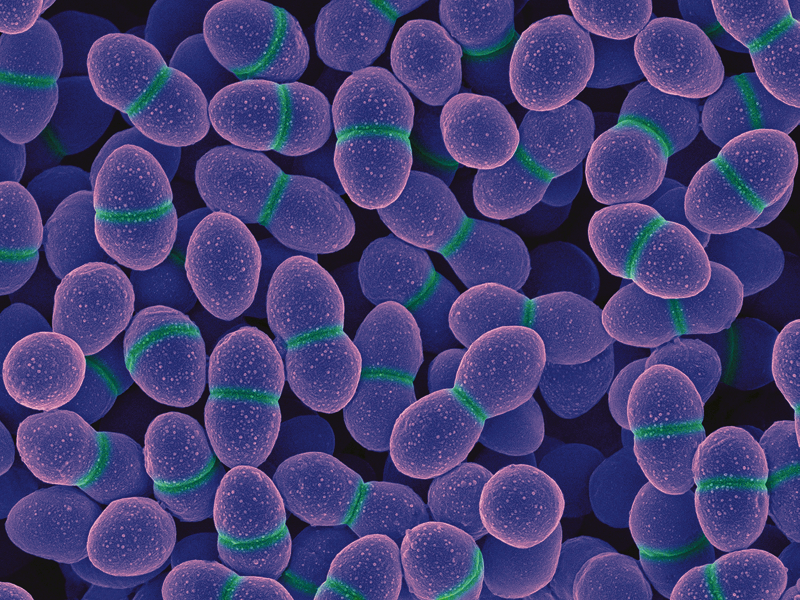

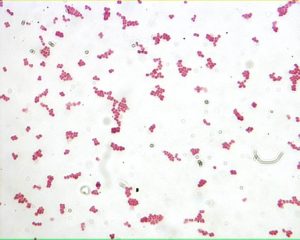

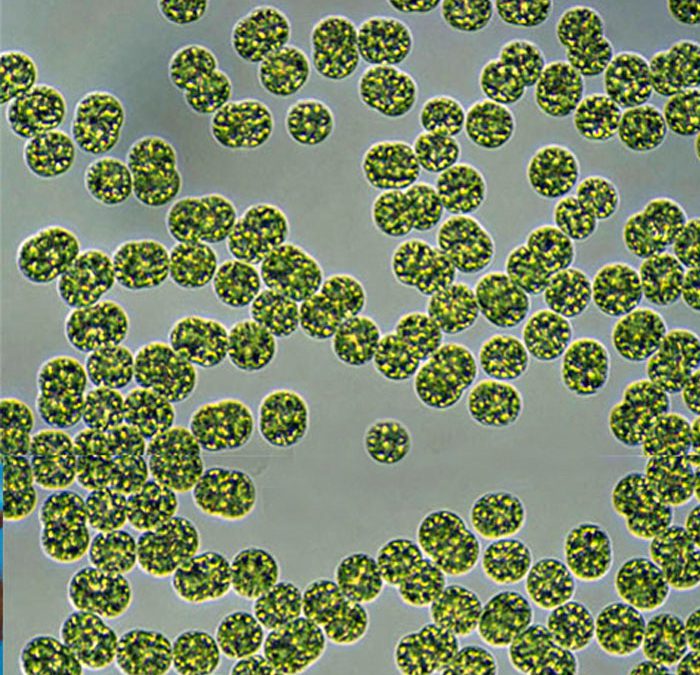

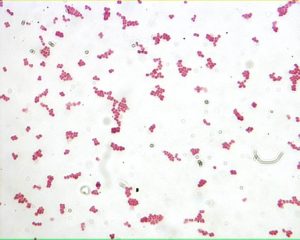

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

Bacteria are single celled creatures, though some “hook” together to form long chains. A single cell will average between 5-10 microns in size. This is much larger than a virus but smaller than many eukaryotic cells (those that possess a nucleus).

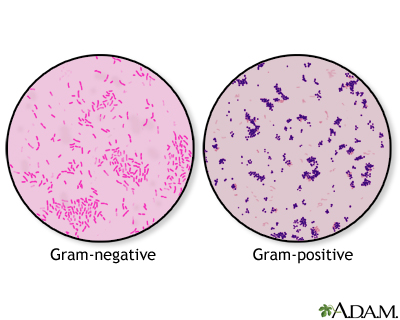

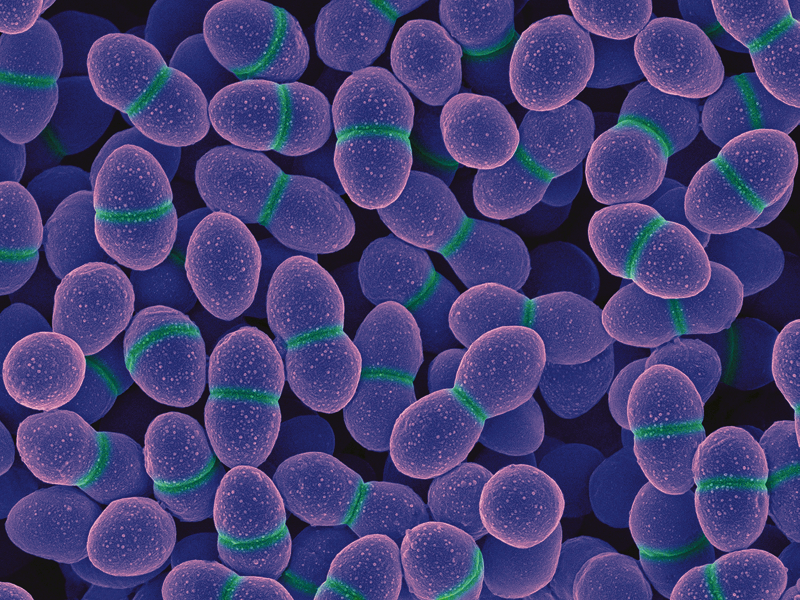

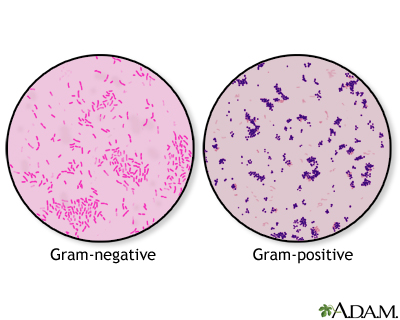

To further classify bacteria microbiologists will conduct a gram-stain test. Placing a cultured sample of bacteria on a slide, you “bath” them in what is called Gram-stain. Under the microscope the bacteria that appear “pink” are called gram negative, those that appear “purple” are gram positive. Thus, all bacteria can be quickly grouped into those that are gram negative and those that are gram positive.

After staining, gram negative bacteria appear pink in color; gram positive are purple.

Image: University of Florida

The next level of classification focuses on the shape of their cells. Those that are “rod-shaped” are called bacillus and often have the term in their name – such as Lactobacillus the bacteria found in milk that makes milk smell sour as their populations grow. The “sphere-shaped” bacteria are called coccus – such as Streptococcus (the bacterium that causes strep throat) and Enterococcus (the fecal bacterium used for monitoring water quality in marine waters). And the third group are “spiral-shaped” and are called spirillum – such as Campylobacter and Helicobacter both are human pathogens.

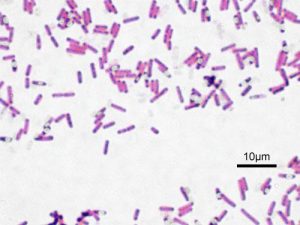

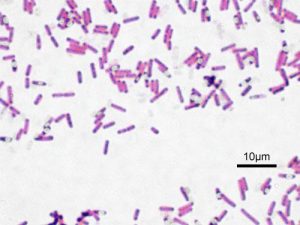

The rod-shaped bacterium known as bacillus.

Image: Wikipedia.

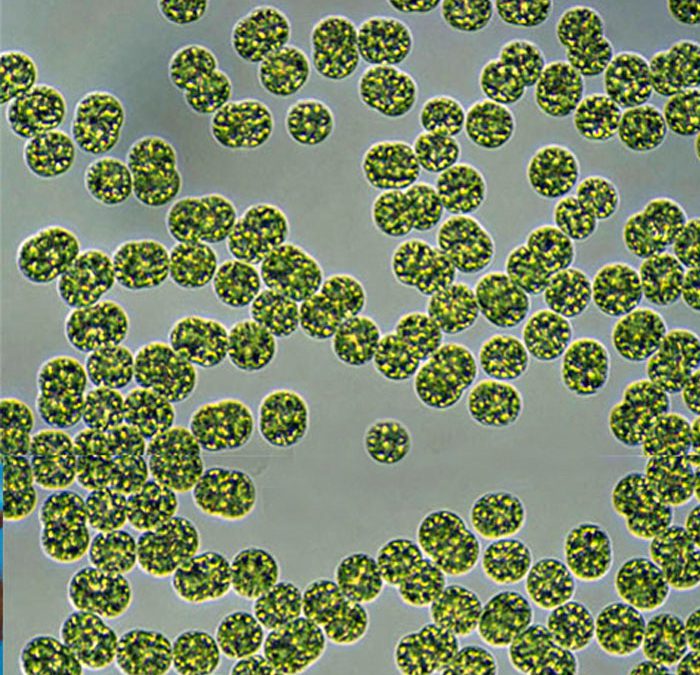

The bacterium known as coccus.

Image: Loyola University

The bacterium known as spirillum.

Image: Lake Superior College.

Bacteria are very abundant in the marine and estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico. They can be found floating in the water column, on the surface of the sediment, beneath the surface of the sediment, and on the bodies of marine organisms. When we think of bacteria we think of “dirty” conditions and disease, but many bacteria provide very important ecological benefits to the marine ecosystem and are “good” members of the community.

One important role some bacteria play is the conversion (“fixing”) of nutrients. Animals release toxic waste when they defecate and urinate. One of these is ammonia. Ammonia can bond with oxygen depleting the body of this needed element. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert toxic ammonia released into the environment into nitrite. Then another group of nitrogen fixing bacteria will convert nitrite into nitrate – a needed nutrient for plants, and eventually the entire food chain.

Some bacteria are excellent decomposers. When plants and animals die we say they “decay”. What is actually happening is the decomposing bacteria are converting nutrients in their bodies to forms that are usable by living organisms. One byproduct of this decomposition process is hydrogen sulfide – which smells like rotten eggs. In biologically productive ecosystems – like swamps and marshes – the smell of hydrogen sulfide is strong – often called “swamp gas”. It is the smell of nutrient conversion and much needed. Though in high concentrations, hydrogen sulfide is toxic as well – there needs to be a balance. We see this same process happenings when we compost food waste to form fertilizers for our gardens.

One place where the smell of sulfur is very strong is near volcanic vents. If you have been to Yellowstone, or a volcano, the smell is very evident. There are what are termed “extreme bacteria” who can live in these very hot, almost toxic, environments. Just as plants take water and carbon dioxide and convert this to sugar in the process of photosynthesis, bacteria can convert toxic forms of sulfur into usable carbohydrates for other living organisms. In the 1970s marine scientists discovered thermal vents on the bottom of the ocean. These hot “chimneys” spew black clouds of smoke into the water column. Approaching these chimneys carefully they found water temperatures between 700-800°F! Living close to these chimneys they found communities of worms, shrimps, fish, and crabs. The walls of the chimneys are actually composed of sulfur fixing bacteria that are converting volcanic minerals and compounds into sugars in a process called chemosynthesis – which supports these deep-sea communities.

The black smokers – hydrothermal vents – found on the ocean floor.

Photo: Woodshole Oceanographic Institute.

Of course, there are more familiar forms of bacteria that cause disease. Called pathogens – they can be problems for all marine life and sometimes humans. Fecal bacteria associated with human waste are not toxic in themselves at low concentrations. However, if their numbers increase (due to a sewage spill, etc.) these, and other possible pathogenic human bacteria, can be a human health issue. The Florida Department of Health monitors the fecal bacteria levels weekly at beaches where humans like to swim. High concentrations will require the department to issue health advisories. We know that all sorts of bacteria begin to replicate quickly in warmer conditions. This can be a problem with seafood that is not kept cold enough before serving. There are federal regulations on what temperatures commercially harvested seafood must be kept in order to be served or sold to the public. Federal and state agencies can monitor the temperatures of stored seafood as it moves from the fishing vessel to the table. But they cannot monitor it from your fishing rod to your table – that responsibility will fall on you. Pathogenic bacteria is the primary reason we refrigerate and/or freeze much of our food.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Though bacteria in general have a bad name, many species are not harmful to us and are a major player in the health of our estuarine and marine communities.

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 4, 2024

Coastal wetlands are some of the most ecologically productive environments on Earth. They support diverse plant and animal species, provide essential ecosystem services such as stormwater filtration, and act as buffers against storms. As Helene showed the Big Bend area, storm surge is devastating to these delicate ecosystems.

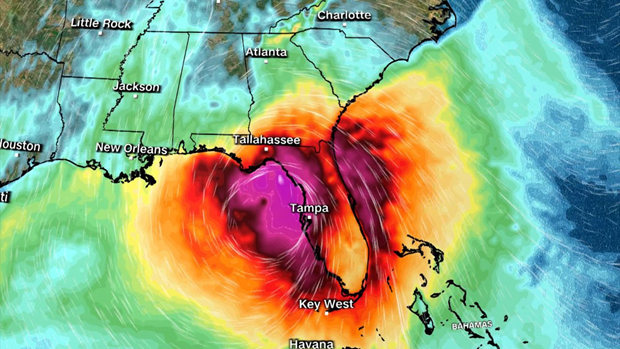

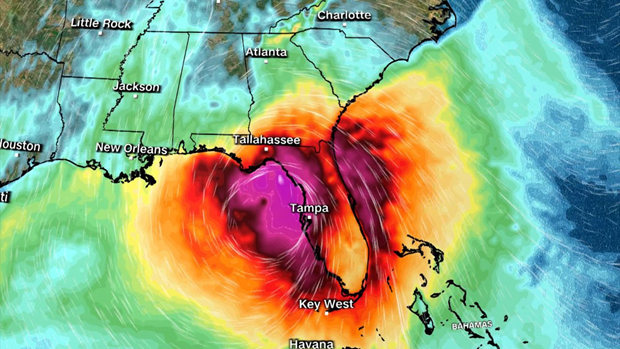

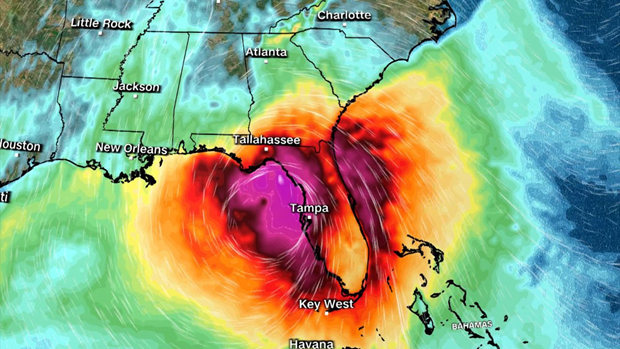

Hurricane Track on Wednesday evening.

As the force of rushing water erodes soil, uproots vegetation, and reshapes the landscape, critical habitats for wildlife, in and out of the water, is lost, sometimes, forever. Saltwater is forced into the freshwater wetlands. Many plants and aquatic animal species are not adapted to high salinity, and will die off. The ecosystem’s species composition can completely change in just a few short hours.

Prolonged storm surge can overwhelm even the very salt tolerant species. While wetlands are naturally adept at absorbing excess water, the salinity concentration change can lead to complete changes in soil chemistry, sediment build-up, and water oxygen levels. The biodiversity of plant and animal species will change in favor of marine species, versus freshwater species.

Coastal communities impacted by a hurricane change the view of the landscape for months, or even, years. Construction can replace many of the structures lost. Rebuilding wetlands can take hundreds of years. In the meantime, these developments remain even more vulnerable to the effects of the next storm. Apalachicola and Cedar Key are examples of the impacts of storm surge on coastal wetlands. Helene will do even more damage.

Many of the coastal cities in the Big Bend have been implementing mitigation strategies to reduce the damage. Extension agents throughout the area have utilized integrated approaches that combine natural and engineered solutions. Green Stormwater Infrastructure techniques and Living Shorelines are just two approaches being taken.

So, as we all wish them a speedy recovery, take some time to educate yourself on what could be done in all of our Panhandle coastal communities to protect our fragile wetland ecosystems. For more information go to:

https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/fflifasufledu/docs/gsi-documents/GSI-Maintenance-Manual.pdf

https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/news/2023/11/29/cedar-key-living-shorelines/

by Laura Tiu | Sep 13, 2024

Western Dune Lake Tour

Walton County in the Florida Panhandle has 26 miles of coastline dotted with 15 named coastal dune lakes. Coastal dune lakes are technically permanent bodies of water found within 2 miles of the coast. However, the Walton County dune lakes are a unique geographical feature found only in Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Oregon, and here in Walton County.

What makes these lakes unique is that they have an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico through an outfall where Gulf water and freshwater flow back and forth depending on rainfall, storm surge and tides. This causes the water salinity of the lakes to vary significantly from fresh to saline depending on which way the water is flowing. This diverse and distinctive environment hosts many plants and animals unique to this habitat.

There are several ways to enjoy our Coastal Dune Lakes for recreation. Activities include stand up paddle boarding, kayaking, or canoeing on the lakes located in State Parks. The lakes are popular birding and fishing spots and some offer nearby hiking trails.

The state park provides kayaks for exploring the dune lake at Topsail. It can be reached by hiking or a tram they provide.

Walton County has a county-led program to protect our coastal dune lakes. The Coastal Dune Lakes Advisory Board meets to discuss the county’s efforts to preserve the lakes and publicize the unique biological systems the lakes provide. Each year they sponsor events during October, Dune Lake Awareness month. This year, the Walton County Extension Office is hosting a Dune Lake Tour on October 17th. Registration will be available on Eventbrite starting September 17th. You can check out the Walton County Extension Facebook page for additional information.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 23, 2024

Roundworms differ from flatworms in that… well… they are round. You might recall from Part 1 of this series that flatworms were flat which helps with exchange of materials inside and out of the body. Flatworms were acoelomates – they lack an interior body cavity and thus lack internal organs. So, gas exchange (etc.) must occur through the skin. And a flat body increases the surface area in order to do this more efficiently.

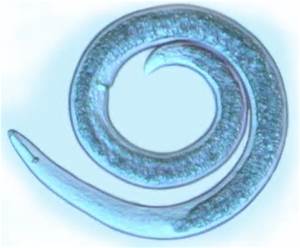

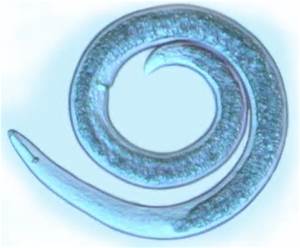

A common nematode.

Photo: University of Florida

But roundworms are round, which reduces this surface area and reduces the efficiency of material exchange through the skin. Though gas exchange through the skin does happen, it is not as efficient. So, there is the need for internal organs and that means there is a need for an internal body cavity to hold these organs. But with the roundworms there is only a partial cavity, not a complete one, and the term pseudocoelomate is used for them. Though the round body has adaptations to deal with gas exchange, it is a better shape for burrowing in the soil and sediment.

There are about 25,000 described species of roundworms, though some estimate there may be at least 500,000. They are placed in the Phylum Nematoda and are often called nematodes. Nematodes live within the interstitial spaces of soil, sediment, and benthic plant communities. They have been found in the polar regions, the tropics, the bottom of the sea, and in deserts – they are everywhere. They are usually in high numbers. One square meter of mud from a beach in Holland had over 4,000,000 nematodes. Scientists have estimated that an acre of farmland may have at least 1 billion of them. A decomposing apple on the ground in an orchard had about 90,000 nematodes. So, they are found everywhere and usually in great abundance. There are parasitic forms as well and they attack almost all groups of plants and animals. Food crops, livestock, and humans have made this group of nematodes a concern in our society.

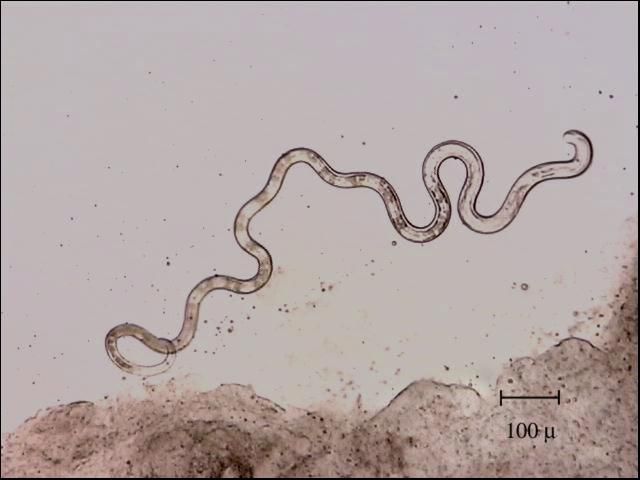

Like many pseudocoelomates, nematodes have an anterior end with a mouth, but no distinct head – rather two tapered ends. Most of the free-living nematodes are less than 3mm (0.1in), but some soil nematodes can reach lengths of 7mm (0.3in) and there are marine nematodes that can reach 5cm (2in.) – it is a group of small worms.

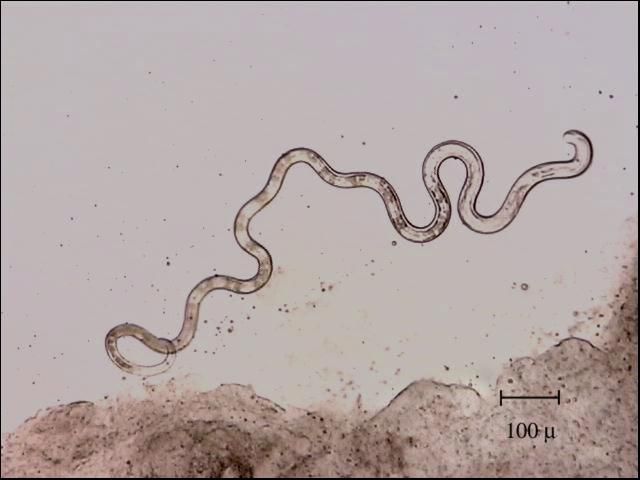

Roundworms usually need water in order to move, even the soil species. They typically wriggle and undulate, similar to a snake, when moving and under a microscope they wriggle quite fast. In aquatic habitats they may swim for a short distance, and a few terrestrial species can crawl through dry sand.

Marine Nematode – Dr. Roy P. E. Yanong, UF/IFAS Tropical Aquaculture Lab

Many free-living nematodes are carnivorous and feed on tiny animals and other nematodes. Some feed on microscopic algae and fungi. Some terrestrial species pierce the roots of plants and digest the material within. Many marine species will feed on detritus lying on the seafloor. The carnivorous species may possess small teeth, and many have a stylet they can use to pierce prey or the plant root to access food. The mouth leads to a long digestive tract and eventually an anus – nematodes have a complete digestive tract.

The brain is basically a nerve ring near the head that leads to numerous nerve chords that run the length of the body. Sensory cells are most associated with the sense of touch and smell.

Having separate sexes is the rule for nematodes, but not for all. Males are usually much smaller and usually have a hooked posterior end which they use to hold the female during mating. 50-100 eggs are usually produced and laid within the environment.

Farmers and horticulturists are familiar with these free-living nematodes, but it is the parasitic ones that are most known to the general public. There are many different forms of parasitism within nematodes. Dr. L.H. Hyman categorized them as follows:

- Ectoparasites that feed on the external cells of plants – using their stylet to pierce the plant tissue and remove nutrients.

- Endoparasites of plants. Juveniles of some nematodes enter plants and feed on tissue. This can cause tissue death and gall-like structures.

- Some free-living nematodes, while juveniles, will enter the bodies of invertebrates and feed on the tissue when the invertebrate dies.

- Endoparasites within invertebrates as juveniles, but the adult stage is free-living.

- Some are plant parasites as juveniles and animal parasites as adults. The females live within the bodies of plant eating insects, where they give birth to their young. When the insects pierce the plant tissue, the juveniles enter the plant and begin feeding on it. When they mature into adults, they re-enter the insects and the cycle begins again.

- Those that live within animals. The eggs, or newly hatched young, may be free-living for a short period, where they find new animal hosts, but the majority of the life cycle occurs within the animal. Many known to us infect dogs, cats, pigs, cattle, horses, chickens, fish, and humans.

Heartworms, pinworms, and hook worms are names you may have heard. For dog nematodes, the eggs are released into the environment by the dog’s feces. Another dog eats this feces and becomes infected.

The nematode known as Ascaris lumbricoides is the most common parasitic worm in humans. It has been estimated that almost 1 billion people are infected with it. Female Ascaris release developing eggs into the environment via human feces. Other humans become infected after swallowing food or water containing the eggs. Once inside the human, the eggs hatch and penetrate the tissue moving into the heart and eventually the lungs. From here they crawl up the trachea inducing a coughing response which is followed by a swallowing response that moves the developing juvenile worm into the esophagus and eventually back to the intestines where the cycle begins again. Infections of this worm are more common where sanitation systems are not adequate and/or human feces are used as a fertilizer.

Hookworms are another human parasite that feed on blood and can cause serious infections in humans due to blood and tissue loss. Fertilized eggs of this worm are laid in the environment and re-enter new human host as developing juveniles by penetrating their skin. Once in the new host the developing worms are carried to the lungs via the circulatory system and work their way into the pharynx, are swallowed, and eventually end up in the intestine. Not all hookworm juveniles penetrate through the skin but rather enter the body when the person unknowingly consumes human feces. This can happen from not washing your hands or food (if human waste is used as fertilizer). Pinworms and whipworms are other nematodes that have similar life cycles. In Asia there are some nematodes that are passed to humans by biting insects.

The roundworm known as the nematode is a common issue for farmers, horticulturists, and as a parasite in some parts of the world. Their lifestyles, while being a potential problem for us, have been very successful for them. In the next edition in this series, we will learn more about the most advanced worms on our planet – the segmented worms. We will begin with the polychaetes.

References

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

Ascaris lumbricoides. 2024. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ascaris_lumbricoides.

by Dana Stephens | Aug 2, 2024

Do you know what is your watershed?

There was, is, and will be the same amount of water on planet Earth. Water is a finite resource. The United States Geologic Survey estimates Earth holds around 1,386,000,000 cubic kilometers of water. Only 330,520 cubic kilometers, less than 1% of all water on Earth, is freshwater. This freshwater is available in the soils, atmosphere, biosphere and used by humans.

We all have different connections with water. Maybe it is swimming. Maybe it is enjoyment of clean laundry. Maybe it is the iconic scenes in the 1992 Academy Award for Best Cinematography, A River Runs Through It. Yet, we all depend on water for life. How and why water moves across a landscape to sustain life is important to us all.

Watersheds in the Continental United States (usgs.gov)

Water located on land is called surface water. Water located underground is called groundwater. A watershed is the area of land where surface water and groundwater drain to a common place. Watersheds vary in size from as small as the size of your foot to as large as the watersheds spanning the continental United States. Larger watersheds are composed of smaller watersheds linked together.

Water gradually flows from higher to lower points in a watershed. Precipitation (i.e., snow, rain and everything in between) collects and moves within the drainage area in the watershed. Not all precipitation falling on a watershed flows out of the watershed. Precipitation soaks into the soil and through porous rock moving to lower points in the watershed, returning to and replenishing water stored underground. This groundwater can return to the surface of the watershed via springs or artesian wells, if the groundwater is under enough pressure.

Water can be removed before flowing out of the watershed as well. Precipitation returns to the atmosphere through evaporation as part of the hydrologic cycle. Plants facilitate evaporation to the atmosphere through transpiration where the roots of plants absorb water from the soil and the water evaporates into the air through the leaves of the plants. Human uses of water also impact how water moves through a watershed. Drinking water supplies, industrial operations, or building dams changes the movement of water through the watershed.

Each of us lives in a watershed. There is much benefit to have healthy watersheds. Healthy watersheds are essential to support ecosystems and the services provided, such as safe drinking water, outdoor recreation, economics, and overall quality of life. There are many metrics and assessments used to measure the health of a watershed. Do you know what is the health of your watershed?

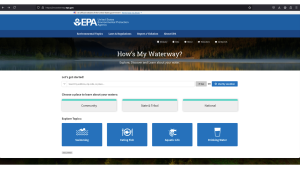

United States Environmental Protection Agency’s How’s My Watershed interactive tool (http://mywaterway.epa.gov)

The United States Environmental Protection Agency developed “How’s My Waterway” to provide the public with information about the condition of their local waters. How’s My Waterway offers three ways to explore your watershed. At the community level, you can see your watershed with details like the water quality, recreation, fish consumption, impairments, and associated plans working to remove impairments. At the state and national levels, you can find information about states/national water program(s) and specific water assessment(s) that affect your watershed.

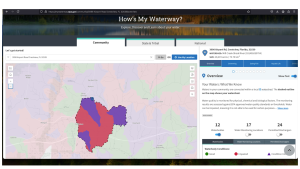

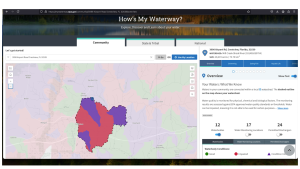

Example–watershed for Okaloosa County UF/IFAS Extension North office.

Let’s give it a try! Go to www.mywaterway.epa.gov in your web browser. Enter the desired address and select >>Go. On the left, you’ll see an interactive map outlining your watershed and the drainage basin(s) that make up the watershed. On the right, there are 10 different tabs allowing you to explore various metrics of the watershed. For example, there is a general tab reviewing the water conditions and states (i.e., good, impaired, or condition unknown) for all surface waters in the watershed. Using the arrow on the right, you can expand each water source to learn specifics about the data-determined state of the water.

Enjoy exploring your watershed! If you have questions about the interactive “How’s My Waterway,” wish to join an educational session to learn more, and/or desire accompanying curriculum, please email Dana Stephens at dlbigham@ufl.edu.

by Ray Bodrey | Jun 3, 2024

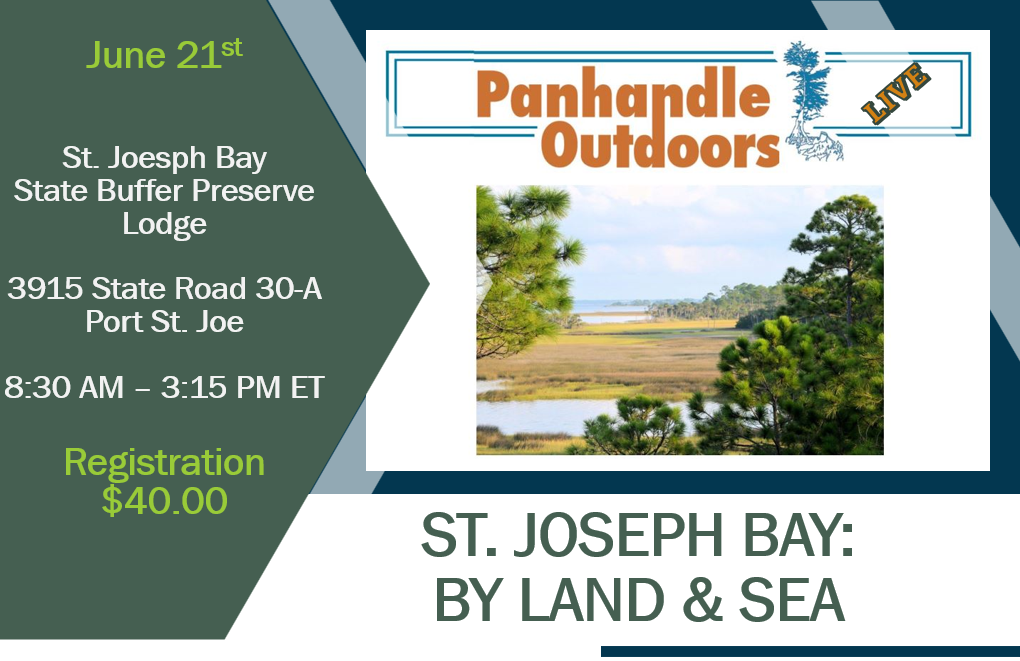

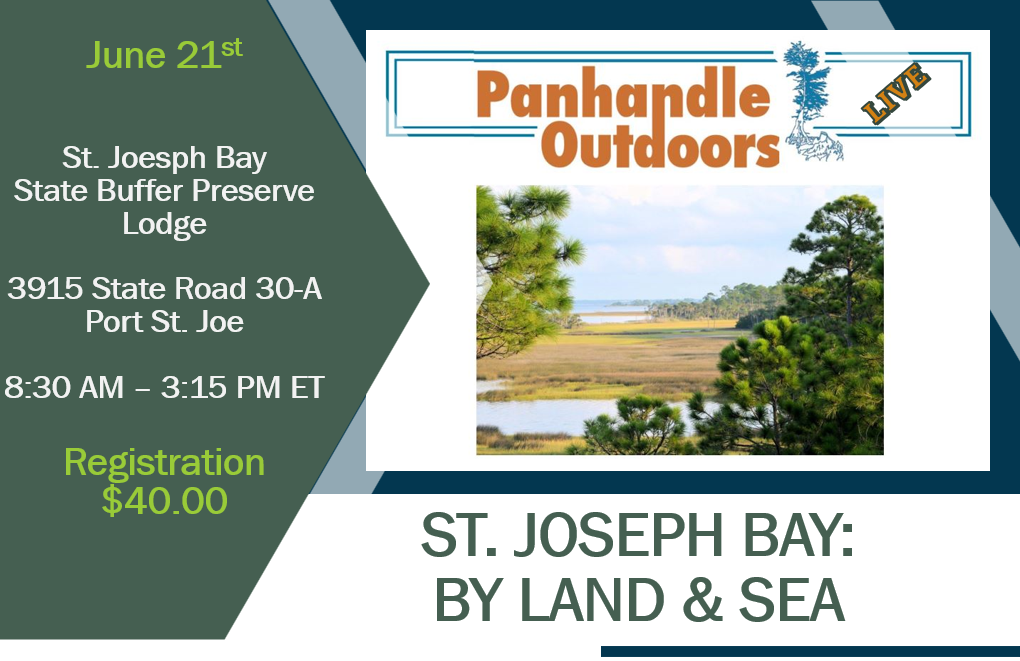

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series on St. Joseph Bay. This ecosystem is home to some of the richest concentrations of flora and fauna on the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles and other species of the marsh and pine flatwoods. Come learn about the important roles of ecosystem!

Registration fee is $40. You must pre-register to attend.

Registration link: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-st-joseph-bay-by-land-sea-tickets-906983109897

or use the QR code:

Meals: Lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sunscreen

*If afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Held at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Lodge: 3915 State Road 30-A, Port St. Joe

| 8:30 – 8:35 Welcome & Introduction – Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension (5 min) |

| 8:35 – 9:20 Diamondback Terrapin Ecology – Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension |

| 9:20 – 10:05 Exploring Snakes, Lizards & the Cuban Tree Frog – Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension |

| 10:05 – 10:15 Break |

| 10:15 – 11:00 The Bay Scallop & Habitat – Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension |

| 11:00 – 11:45 The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Derelict Vessel Program – Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension |

| 11:45 – Noon Question & Answer Session – All Agents |

| Noon – 1:00 Pizza & Salad! |

| 1:00 – 1:20 Introduction to the Buffer & History – Buffer Preserve Staff |

| 1:20 – 2:20 Tram Tour – Buffer Preserve Staff |

| 2:20 – 2:30 Break |

| 2:30 – 3:00 A Walk in the Mangroves – All Agents |

| 3:00 – 3:15 Wrap up & Adjourn – All |