by Sheila Dunning | Sep 29, 2022

October has been designated as Coastal Dune Lake Appreciation month by Walton County government. Walton County is home to 15 named coastal dune lakes along 26 miles of coastline. These lakes are a unique geographical feature and are only found in a few places in the world including Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Oregon, and here in Walton County.

A coastal dune lake is defined as a shallow, irregularly shaped or elliptic depressions occurring in coastal communities that share an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico through which freshwater and saltwater is exchanged. They are generally permanent water bodies, although water levels may fluctuate substantially. Typically identified as lentic water bodies without significant surface inflows or outflows, the water in a dune lake is largely derived from lateral ground water seepage through the surrounding well-drained coastal sands. Storms occasionally provide large inputs of salt water and salinities vary dramatically over the long term.

Our coastal dune lakes are even more unique because they share an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico, referred to as an “outfall”, which aides in natural flood control allowing the lake water to pour into the Gulf as needed. The lake water is fed by streams, groundwater seepage, rain, and storm surge. Each individual lake’s outfall and chemistry is different. Water conditions between lakes can vary greatly, from completely fresh to significantly saline.

Our coastal dune lakes are even more unique because they share an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico, referred to as an “outfall”, which aides in natural flood control allowing the lake water to pour into the Gulf as needed. The lake water is fed by streams, groundwater seepage, rain, and storm surge. Each individual lake’s outfall and chemistry is different. Water conditions between lakes can vary greatly, from completely fresh to significantly saline.

A variety of different plant and animal species can be found among the lakes. Both freshwater and saltwater species can exist in this unique habitat. Some of the plant species include: rushes (Juncus spp.), sedges (Cyperus spp.), marshpennywort (Hydrocotyle umbellata), cattails (Typha spp.), sawgrass (Cladium jamaicense), waterlilies (Nymphaea spp.), watershield (Brasenia schreberi), royal fern (Osmunda regalis var. spectabilis), rosy camphorweed (Pluchea spp.), marshelder (Iva frutescens), groundsel tree (Baccharis halimifolia), and black willow (Salix nigra).

Some of the animal species that can be found include: western mosquitofish (Gambusia affinis), sailfin molly (Poecilia latipinna), American alligator (Alligator mississippiensis), eastern mud turtle (Kinosternon subrubrum), saltmarsh snake (Nerodia clarkii ssp.), little blue heron (Egretta caerulea), American coot (Fulica americana), and North American river otter (Lutra canadensis). Many marine species co-exist with freshwater species due to the change in salinity within the column of water.

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series. Come celebrate Coastal Dune Lake Appreciation month as our team provides a guided walking tour of the nature trail surrounding Western Lake in Grayton Beach State Park. Join local County Extension Agents to learn more about our globally rare coastal dune lakes, their history, surrounding ecosystems, and local protections. Walk the nature trail through coastal habitats including maritime hammocks, coastal scrub, salt marsh wetlands, and coastal forest. A tour is available October 19th.

The tour is $10.00 (plus tax) and you can register on Eventbrite (see link below). Admission into the park is an additional $5.00 per vehicle, so carpooling is encouraged. We will meet at the beach pavilion (restroom facilities available) at 8:45 am with a lecture and tour start time of 9:00 am sharp. The nature trail is approximately one mile long, through some sandy dunes (can be challenging to walk in), on hard-packed trails, and sometimes soggy forests. Wear appropriate footwear and bring water. Hat, sunscreen, camera, binoculars are optional. Tour is approximately 2 hours. Tour may be cancelled in the event of bad weather.

Register here on Eventbrite: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoor-live-coastal-dune-lake-lecture-and-nature-trail-tour-tickets-419061633627

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 21, 2022

Part of our job at Extension is to help enhance science literacy. Often we write about natural history topics of interest to community that focus on interesting wildlife or an environmental issue or on topic we think the public should know more about. These articles have good science in them but are often written in a way as to not be too “sciencey” so that public will not be lost in the message. But sometimes there is a need for “sciencey” articles. Ones that may explain things using concepts and terms that go deeper than the public usually like to go. Not that the public cannot understand this, it is just too much like a science class from high school and not everyone enjoyed science when they were in school. A topic they may not enjoy. We are going to try a “sciencey” topic for this article.

What is salinity?

Most have heard the term and usually associate it with how much salt is in the water. They are not incorrect, and for the most part this definition will suffice when using it in conversation. But it actually goes a bit deeper than that. We will start with what is a salt.

Salt crystals used to de-ice roads.

Photo: University of South Florida

A salt is the product of an acid and a base. For example, when you combine hydrochloric acid and sodium hydroxide you get sodium chloride (salt) and water.

HCl + NaOH – HOH (H2O) + NaCl

Most recognize sodium hydroxide as common table salt. But to better understand the point let’s combine sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide.

H2SO4 + NaOH – H2OH (H2O) + NaSO4

Sodium sulfate (NaSO4) would also be a salt. There are numerous salts found in the environment. They are found in rock and mineral forms from land and the seafloor and will eventually make their way into the ocean – where of course they meet water.

Water has been described as the “universal solvent” and that is because water is a polar molecule and dissolves most things. What does “being polar” that mean?

We understand that “polar” means opposite ends, and in this case one end is positively charged, and the other is negative. This has to do with the alignment of the element’s hydrogen and oxygen in the molecule. To explain the alignment would require more chemistry than we want to go into here. But let’s just say the outer suborbital requires eight electrons to be considered stable – even that will take more discussion.

We know that atoms are made of protons, neutrons, and electrons. The protons and neutrons combine to form the nucleus of the atom while the electrons orbit around the nucleus like the moon orbits around the earth. Well, not exactly like that but that description will suffice to get the idea across. The orbit closest to the nucleus can only hold two electrons, any additional electrons will be forced to another orbit further away. If there are no additional electrons there are no additional orbits.

These orbits are identified by letters. The one closest to the nucleus is an s orbital. S orbitals can only hold two electrons. The next orbit out will have an s orbital and a p orbital. Again, the s can hold two, but the p can hold six. So, the second orbit can hold a total of eight electrons – 2 in the s orbital of the second orbit and another 6 in the p orbital of the second orbit (there is not a p orbital in the first orbit). If the atom has more than 10 electrons (2 in the first orbit and 8 in the second) then there will be a third orbit that has an s orbital (holding 2 electrons), a p orbital (holding 6 electrons) and a new orbital called d (which can hold 10 electrons). And so, it goes. Large atoms with lots of electrons will have lots of orbits with several orbitals holding a fix number of electrons. This may be getting more “sciencey” than we wanted, but we will continue to plow forward to help better understand salinity.

Here is the kicker. The s and p orbitals together hold a total of 8 electrons and the s and p orbitals of the orbit farthest from the nucleus MUST be filled for the atom to be stable. If they are not, then the atom is looking to gain or lose electrons to do so. Let’s look at water, we will start with oxygen.

Oxygen has the atomic number of 8. This means it has eight protons and eight electrons. Protons are positively charged, and electrons are negatively charged. Thus, oxygen has eight protons (+8) and eight electrons (-8). The charges cancel each other out and the atom is neutrally charged. But let’s look at how those eight electrons fill the orbits.

Remember the orbit closest to the nucleus only had an s orbital and can hold two electrons, which is does. But this leaves six electrons to place. The second orbit has an s and an p. S can only hold 2 electrons, so 2 of the 6 will go there. The p can hold 6, but now the oxygen atom only has 4 electrons left (after filling the first two s orbitals). So, it places those remaining four in the p orbital. But the p orbital is not full. It will hold 6 but only has 4. It has two empty orbitals and those MUST be filled. It needs 2 electrons from somewhere. (see below).

Filled s1 2 s2 2 p2 6

Oxygen s1 2 s2 2 p2 4 – it needs two electrons

Where does it find two electrons to become stable?

Let’s look hydrogen.

Hydrogen has the atomic number of 1. It has one proton (+1) and one electron (-1). Its orbit configuration would look like this:

Filled s1 2

Hydrogen s1 1 – it needs one electron to fill

Remember if you do not have enough electrons for a second orbit, there is no second orbit. BUT as you see the first orbit of hydrogen (which needs 2) only has 1 electron. It is not full.

Let’s look at another example to first understand how MOST atoms deal with this problem.

Sodium has the atomic number of 11. Eleven protons (+11) and eleven electrons (-11)

Chlorine has the atomic number of 17. Seventeen protons (+17) and seventeen electrons (-17). They would fill their orbits, and orbitals, as follows.

Na s1 2 s2 2 p2 6 s3 1

Cl s1 2 s2 2 p2 6 s3 2 p3 6 s4 1

You can see that the last sp for both are not full. However, if sodium “gives” the electron in s3 to chlorine then it’s s3 orbital is gone and the sp2 for the second orbit of sodium would be full – stable. Likewise, if chlorine “accepted” that electron its s4 orbital would be full – stable. And this is what happens. However, this throws the electronic balance off.

If sodium is (+11) (-11) and gives away an electron it is now (+11) (-10) – no longer neutral. It becomes positively charged (+1) and charged atoms are called ions (Na+1). Likewise, chlorine accepting the electron (+17) (-18) would form a negative ion (-1) (Cl-1). Opposite charges attract with Na+1 and Cl-1 combine to form NaCl – salt. This is known as an ionic bond. Two oppositely charged ions combining to form a compound.

Water is a bit different.

Hydrogen s1 1

Oxygen s1 2 s2 2 p2 4

You can see oxygen needs 2, but hydrogen does not have 2 to give AND if it gives the ONLY electron, it has it will no longer exist. So, it SHARES its 1 electron with oxygen. The hydrogen atom will allow its lone electron to orbit the last orbital of oxygen BUT it must circle back and orbit the hydrogen nucleus as well. To get the required 2 electrons that oxygen needs to fill its sp2 it will need another hydrogen atom to do so – hence H2O. When sharing electrons to form a compound we call this a covalent bond.

Now comes the alignment part.

To graphically illustrate how the electrons fill the last sp orbitals of an element they use what is called the electron-dot. It would be laid out as follows:

S **

p Na p if full would look like this ** Na **

p **

The first two electrons would fill the s orbital. Then any additional electrons filling the p’s BUT you would first place an electron in each p and then come back and fill (two max) in clockwise form. The number AND ALIGNMENT of the electrons would be represented by dots.

In the example just given – sodium – the atomic number is 11. The eleven electrons would be placed as follows

s1 – (2) s2 (2) p2 (6) s3 (1) The electron dot would look like *

Na

Chlorine (17) would look like this…

s1 (2) s2 (2) p2 (6) s3 (2) p3 (5)

**

**

You can see the open space for one electron to fill this and complete the two for each. Sodium would GIVE it’s one electron to chlorine (having a full s2p2 with eight dots all around) forming an ionic bond known as sodium chloride (NaCl) or salt. The next inner orbit of sodium would have its sp orbitals filled and would be stable but charged due to having more protons than electrons.

Oxygen (8) would look like this…

s1 (2) s2 (2) p2 (4)

**

*

This alignment would force the two hydrogen atoms SHARING electrons to do so NEXT to each other.

Water would appear like this…

**

H** O **

H **

The water molecule.

Image: Florida Atlantic University

In the sharing of the electrons to form water the oxygen molecule holds the electrons longer than the hydrogen (it is larger). This makes hydrogen slightly positive and oxygen negative. Due to this alignment with both hydrogens at one end of the water molecule gives it a positive and negative end – it is polar – it has opposite poles – a positive and negative one. It acts like a magnet.

The first impact of this situation is that water molecules attach to each other. The positive hydrogen end of one water molecule attaches to the negative oxygen end of another. All of the water molecules bond together and form a lattice of water molecules – like they are all holding hands. These bonds are weak and can be easily broken if a creature is trying to swim through them, but attached they are.

A second impact is that they will disassociate (dissolve) ionic compounds that they come in contact with, like salts. The ionic bond we know as salt – sodium chloride (Na+Cl–) will dissolve in water. The positive ion Na+ is attracted to the negative end of the water molecule. The opposite is true for the chlorine ion.

So, what is actually “drifting” around in the water are dissolved ions – not the salts themselves. Which salts and ions are drifting in seawater? All of them. All 92 natural elements found on the planet are dissolved in seawater – not just sodium and chloride. It is true that the sodium and chloride ions make up about 85% of all the dissolved ions in seawater, but not all. So “sea salt” looks and taste like table salt but it is different.

Salinity then is the measure of dissolved solids (or ions) in the water – not exactly salt.

How salty is the water? What is its salinity?

We can measure this several ways.

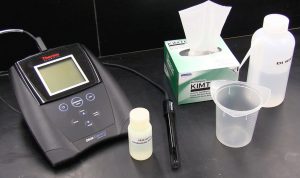

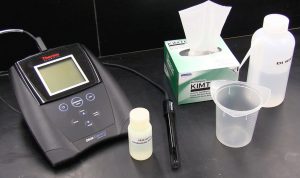

Conductivity meter.

Photo: Iowa State University

Being that you are measuring the amount of dissolved charged ions in the water you can use a conductivity meter. Conductivity is the measure of the ease of which an electric charge (or heat) can pass through a material. The more ions dissolved in the water the higher the conductivity. This can be measured easily with the conductivity meter. Though conductivity is NOT a measure of the amount of ions in the water, but rather the measure of how easily an electric current passes through the water, it is still very closely related to the amount (or salinity) and is often used (making corrections) to determine the salinity of the water.

Hydrometer.

Photo: University of Queensland

Another method is measuring the density of the water. The more dissolved ions in the water the denser it is. A hydrometer is a glass tube filled with a fixed amount of lead shot with a calibrated stem (you can get them with different amounts of lead to measure salinity at a wider range). As you place it in the sample, the density of the water holds the hydrometer in specific position and you can read the salinity from the calibrated stem.

Refractometer

Playing off the density game. The denser the water is the more it will refract light passing through it. A refractometer is an instrument that uses a calibrated scale to measure salinity based on much light passing through refracts (or bends). The volunteers monitoring salinity in our citizen science project are using this method.

Salinity is measured in parts per thousand – parts of salt to 1000 parts of water. Using any of these instruments, or one called a salinity meter which works similar to a conductivity meter but is calibrated to salinity not conductivity, you can determine the salinity of the water.

0 parts per thousand (ppt, ‰) would be freshwater water.

35 ‰ would be seawater.

Salinities between 0 and 35 ‰ would be brackish water.

These values are not set in stone.

Many scientists argue that anything above 0 ‰ is not freshwater. I have read salinities in Perdido River as high as 4 ‰ and it did not taste like salt water. Some would say that up to 5 ‰ could still be considered freshwater – but again, not everyone agrees. One must also understand that in nature there are always SOME dissolved ions in the water. It is just their concentrations are SO low that our instruments cannot detect and give a reading of 0 ‰.

Likewise, the salinity of the Gulf of Mexico can run between 30 – 38 ‰, the average is 35 ‰.

Usually, the salinities in the lower parts of the Pensacola Bay system run between 20-30 ‰.

The bayous are typically between 10-20 ‰.

And the upper portions of the bay run between 0-10 ‰.

There are exceptions.

Bayou Chico usually runs between 0-10 ‰ but readings above 10 ‰ are found near the lower end of the bayou.

Perdido Bay is lower than Pensacola Bay. Lower Perdido Bay averages between 10-20 ‰.

Note: The tide plays a role in what the salinity is at any given moment. High tide brings in more saline water, to any system that experiences tides, and the salinity will be higher at that time.

For reasons we will not go into here, many of the plants and animals that call our waters home have specific salinities they prefer. There is a range they can tolerate, but also a smaller range they prefer. The biology of the upper and lower bays can be very different. The seagrass known as tape grass, or eel grass (Vallisneria) prefers low salinities, typically under 10 ‰, and are found in the upper reaches of the bay. Whereas shoal grass (Halodule) and turtle grass (Thalassia) prefer it above 20 ‰ and more common in the lower reaches. Some species, like turtle grass, have a small range of salinity they can tolerate and are called stenohaline species. Others, like shoal grass or widgeon grass (Ruppia), have a much broader range and can be found in many waterways within the bay system. These are called euryhaline.

Sea Grant is currently looking at the salinity across the bay area (from shore) to determine how (if at all) the excessive amount of rain we have been receiving in the Pensacola area in recent years is impacting the salinity of the system. As we described above, this could impact those stenohaline species who cannot tolerate it. We hope to conduct a more robust salinity monitoring project in the future.

Hopefully this was not too “sciencey” and that you learned something new about the salinity of our bay.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 14, 2022

Scallops…

We used to find them here. I have heard stories of folks who could fill a 5-gallon bucket with them in about 30 minutes right by Morgan Park. An old shrimper told me that back in the day when shrimping in Santa Rosa Sound they often found scallops along the points. They would drop a grab and collect them for sale. This was when both commercial scallop harvest, and shrimping, were allowed in Santa Rosa Sound. Neither are today. There are numerous tales of large beds of scallops in Big Lagoon and scientific reports of their presence in both locations and in Little Sabine. I myself have found them at Naval Live Oaks, Shoreline Park, Big Sabine, and in Big Lagoon.

Bay scallops need turtle grass to survive.

Photo: UF IFAS

But that was a long time ago. The reports suggest the decline began in the 1960s and today it is rare to find one. What happen is hard to say but most believe it began with a decline in water quality. A decrease in salinity and an increase in nutrients from stormwater runoff degraded the environment for both the scallops and the turtle seagrass they depend on. Overharvesting certainly played a role.

But they are not all gone. There is still turtle grass in our system and occasionally reports of scallops. They are trying to hang on. There have also been attempts to improve water quality by modifying how stormwater is discharged into our bay, though there is much more to do there. Each year Florida Sea Grant Agents at our local county extension offices provide volunteers an opportunity to survey our bay for both species. We have a program called “Eyes on Seagrass” where volunteers monitor sites with seagrass once a month from April through October. We partner with Dr. Jane Caffrey from the University of West Florida to assess this. We also hold our annual “Pensacola Bay Scallop Search” each July.

In the Scallop Search volunteers will snorkel four different 50-meter transects lines either in Santa Rosa Sound or Big Lagoon searching for scallops. These surveys are conducted at the end of July. There are 11 survey grids in Big Lagoon and 55 in Santa Rosa Sound extending from Gulf Breeze to Navarre. To volunteer you will need a team of at least three people and your own snorkel gear. Some locations do require a boat to access. If you are interested in searching along the north shore of Santa Rosa Sound contact Chris Verlinde at chrismv@ufl.edu (850-623-3868). If you are interested in searching along the south shore of Santa Rosa Sound, or Big Lagoon, contact Rick O’Connor at roc1@ufl.edu (850-475-5230).

Volunteers conducting the great scallop search.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Reminder, harvesting scallops in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties is still illegal. Please give them a chance to recover.

by Ray Bodrey | Jul 11, 2022

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series. Conservation lands and aquatic systems have vulnerabilities and face future threats to their ecological integrity. Come learn about the important role of these ecosystems.

The St. Joseph Bay and Buffer Preserve Ecosystems are home to some of the one richest concentrations of flora and fauna along the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles, salt marshes and pine flatwoods uplands.

This one-day educational adventure is based at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve near the coastal town of Port. St. Joe, Florida. It includes field tours of the unique coastal uplands and shoreline as well as presentations by area Extension Agents.

Details:

Registration fee is $45.

Meals: breakfast, lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sun screen

*if afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Space is limited! Register now! See below.

Tentative schedule:

All Times Eastern

8:00 – 8:30 am Welcome! Breakfast & Overview with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

8:30 – 9:35 am Diamondback Terrapin Ecology, with Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension

9:35 – 9:45 am Q&A

9:45- 10:20 am The Bay Scallop & Habitat, with Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension

10:20 – 10:30 am Q&A

10:30 – 10:45 am Break

10:45 – 11:20 am The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Marine Debris, with Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension

11:20 – 11:30 am Q&A

11:30 – 12:05 am The Apalachicola Oyster, Then, Now and What’s Next, with Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension

12:05 – 12:15 pm Q&A

12:15 – 1:00 pm Lunch

1:00 – 2:30 pm Tram Tour of the Buffer Preserve (St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Staff)

2:30 – 2:40 pm Break

2:40 – 3:20 pm A Walk Among the Black Mangroves (All Extension Agents)

3:20 – 3:30 pm Wrap Up

To attend, you must register for the event at this site:

https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-at-st-joseph-bay-tickets-404236802157

For more information please contact Ray Bodrey at 850-639-3200 or rbodrey@ufl.edu

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 1, 2022

One of the programs I focus on as a Sea Grant Extension Agent in Escambia County is restoring the health of our estuary. One of the projects in that program is increasing the encounters with estuarine animals that were once common. Currently I am focused on horseshoe crabs, diamondback terrapins, and bay scallops. Horseshoe crabs and bay scallops were more common here 50 years ago. We are not sure how common diamondback terrapins were. We know they were once very common near Dauphin Island and are often found in the Big Bend area, but along the emerald coast we are not sure. That said, we would like to see all of them encountered more often.

Horseshoe crabs breeding on the beach.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

There are a variety of reasons why species decline in numbers, but habitat loss is one of the most common. Water quality declined significantly 50 years ago and certainly played a role in the decline of suitable habitat. The loss of seagrass certainly played a role in the decline of bay scallops, but overharvesting was an issue as well. In the Big Bend region to our east, horseshoe crabs are also common in seagrass beds and the decline of that habitat locally may have played a role in the decline of that animal in our bay system.

Salt marshes are what terrapins prefer. We have lost a lot of marsh due to coastal development. Unfortunately, marshes often exist where we would like houses, marinas, and restaurants. If the decline of these creatures in our bay is a sign of the declining health of the system, their return could be a sign that things are getting better.

Seagrass beds have declined over the last half century.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Salt marshes have declined due to impacts from coastal development.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

For over 10 years we have been conducting citizen science monitoring programs to monitor the frequency of encounters of these creatures. All three are here but the increase in encounters has been slow. An interesting note was the fact that many locals had not heard of two of them. Very few knew what a horseshoe crab was when I began this project and even fewer had heard of a terrapin. Scallops are well known from the frequent trips locals make to the Big Bend area to harvest them (the only place in the state where it is legal to do so), but many of those were not aware that they were once harvested here.

I am encouraged when locals send me photos of either horseshoe crabs or their molts. It gives me hope that the animal is on the increase. Our citizen science project focuses on locating their nesting beaches, which we have not found yet, but it is still encouraging.

Horseshoe crab molts. Photo UF/IFAS Communications

Mississippi Diamondback Terrapin (photo: Molly O’Connor)

Volunteers surveying terrapin nesting beaches do find the turtles and most often sign that they have been nesting. The 2022 nesting season was particularly busy and, again, a good sign.

It is now time to do our annual Scallop Search. Each year we solicit volunteers to survey a search grid within either Big Lagoon or Santa Rosa Sound. Over the years the results of these surveys have not been as positive as the other two, but we do find them, and we will continue to search. If you are interested in participating in this year’s search, we will be conducting them during the last week of July. You can contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office (850-475-5230 ext.1111) or email roc1@ufl.edu or Chris Verlinde at the Santa Rosa County Extension Office (850-623-3868) or email chrismv@ufl.edu and we can set you up.

Bay scallops need turtle grass to survive.

Photo: UF IFAS

Volunteers participating in the Great Scallop Search.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Final note…

Each June I camp out west somewhere and each year I look for those hard-to-find animals. After 10 years of looking for a mountain lion, I saw one this year. Finding these creatures can happen. Let’s hope encounters with all three become more common in our bay.

by Scott Jackson | May 26, 2022

Nutrients found in food waste are too valuable to just toss away. Small scale composting and vermicomposting provide opportunity to recycle food waste even in limited spaces. UF/IFAS Photo by Camila Guillen.

During the summer season, my house is filled with family and friends visiting on vacation or just hanging out on the weekends. The kitchen is a popular place while waiting on the next outdoor adventure. I enjoy working together to cook meals, bbq, or just make a few snacks. Despite the increased numbers of visitors during this time, some food is leftover and ultimately tossed away as waste. Food waste occurs every day in our homes, restaurants, and grocery stores and not just this time of year.

The United States Food and Drug Administration estimates that 30 to 40 percent of our food supply is wasted each year. The United States Department of Agriculture cites food waste as the largest type of solid waste at our landfills. This is a complex problem representing many issues that require our attention to be corrected. Moving food to those in need is the largest challenge being addressed by multiple agencies, companies, and local community action groups. Learn more about the Food Waste Alliance at https://foodwastealliance.org

According to the program website, the Food Waste Alliance has three major goals to help address food waste:

Goal #1 REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF FOOD WASTE GENERATED. An estimated 25-40% of food grown, processed, and transported in the U.S. will never be consumed.

Goal #2 DONATE MORE SAFE, NUTRITIOUS FOOD TO PEOPLE IN NEED. Some generated food waste is safe to eat and can be donated to food banks and anti-hunger organizations, providing nutrition to those in need.

Goal #3 RECYCLE UNAVOIDABLE FOOD WASTE, DIVERTING IT FROM LANDFILLS. For food waste, a landfill is the end of the line; but when composted, it can be recycled into soil or energy.

All these priorities are equally important and necessary to completely address our country’s food waste issues. However, goal three is where I would like to give some tips and insight. Composting food waste holds the promise of supplying recycled nutrients that can be used to grow new crops of food or for enhancing growth of ornamental plants. Composting occurs at different scales ranging from a few pounds to tons. All types of composting whether big or small are meaningful in addressing food waste issues and providing value to homeowners and farmers. A specialized type of composting known as vermicomposting uses red wiggler worms to accelerate the breakdown of vegetable and fruit waste into valuable soil amendments and liquid fertilizer. These products can be safely used in home gardens and landscapes, and on house plants.

Composting meat or animal waste is not recommended for home composting operations as it can potentially introduce sources of food borne illness into the fertilizer and the plants where it is used. Vegetable and Fruit wastes are perfect for composting and do not have these problems.

Composting worms help turn food waste into valuable fertilizer. UF/IFAS Photo by Tyler Jones

Detailed articles on how vermicomposting works are provided by Tia Silvasy, UF/IFAS Extension Orange County at https://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/orangeco/2020/12/10/vermicomposting-using-worms-for-composting and https://sfyl.ifas.ufl.edu/media/sfylifasufledu/orange/hort-res/docs/pdf/021-Vermicomposting—Cheap-and-Easy-Worm-Bin.pdf Supplies are readily available and relatively inexpensive. Please see the above links for details.

A small vermicomposting system would include:

• Red Wiggler worms (local vendors or internet)

• Two Plastic Storage Bins (approximately 30” L x 20” W x 17” H) with pieces of brick or stone

• Shredded Paper (newspaper or other suitable material)

• Vegetable and Fruit Scraps

Red Wiggler worms specialize in breaking down food scraps unlike earthworms which process organic matter in soil. Getting the correct worms for vermicomposting is an important step. Red Wigglers can consume as much as their weight in one day! Beginning with a small scale of 1 to 2 pounds of worms is a great way to start. Sources and suppliers can be readily located on the internet.

Worm “homes” can be constructed from two plastic storage bins with air holes drilled on the top. Additional holes put in the bottom of the inner bin to drain liquid nutrients. Pieces of stone or brick can be used to raise the inner bin slightly. Picture provided by UF/IFAS Extension Leon County, Molly Jameson

Once the worms and shredded paper media have been introduced into the bins, you are ready to process kitchen scraps and other plant-based leftovers. Food waste can be placed in the worm bins by moving along the bin in sections. Simply rotate the area where the next group of scraps are placed. See example diagram. For additional information or questions please contact our office at 850-784-6105.

Placing food scraps in a sequential order allows worms to find their new food easily. Contributed diagram by L. Scott Jackson

Portions of this article originally published in the Panama City News Herald

UF/IFAS is An Equal Opportunity Institution.

Our coastal dune lakes are even more unique because they share an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico, referred to as an “outfall”, which aides in natural flood control allowing the lake water to pour into the Gulf as needed. The lake water is fed by streams, groundwater seepage, rain, and storm surge. Each individual lake’s outfall and chemistry is different. Water conditions between lakes can vary greatly, from completely fresh to significantly saline.

Our coastal dune lakes are even more unique because they share an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico, referred to as an “outfall”, which aides in natural flood control allowing the lake water to pour into the Gulf as needed. The lake water is fed by streams, groundwater seepage, rain, and storm surge. Each individual lake’s outfall and chemistry is different. Water conditions between lakes can vary greatly, from completely fresh to significantly saline.