by Rick O'Connor | Jul 27, 2016

Who does not like St. Joseph Bay! What a place… One of the more pristine estuaries in Florida, St. Joe is famous for its snorkeling, fishing, kayaking, and scalloping.

15 miles long and 6 miles across (at its widest point), St. Joe Bay has no significant freshwater input. It’s only opening is to the north and into the Gulf of Mexico. Because of the high salinity in the bay the seagrasses flourish. There are five known species that exist here and the meadows cover almost one sixth of the bottom. Healthy grasses mean diverse wildlife – and St. Joe Bay has it. Migratory birds, octopus, sea turtles, sport fish, urchins, and of course scallops.

The UF/IFAS Extension Natural Resource Agents will be hosting one of their water school programs in St. Joe Bay in September. This two-day program will offer presentations by specialists on a variety of topics, hikes through the uplands, visits to the salt marsh, and a kayak/snorkel trip into the seagrasses themselves. We will be staying at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve in Port St. Joe. For more information about this program contact Erik Lovestrand at (850) 653-9337 or elovestrand@ufl.edu.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 22, 2016

The Deepwater Horizon (DWH) oil spill occurred about 50 miles offshore of Louisiana in April 2010. Approximately 172 million gallons of oil entered the Gulf of Mexico. Five years after the incident, locals and tourists still have questions. This article addresses the five most common questions.

QUESTION #1: Is Gulf seafood safe to eat?

Ongoing monitoring has shown that Gulf seafood harvested from waters that are open to fishing is safe to eat. Over 22,000 seafood samples have been tested and not a single sample came back with levels above the level of concern. Testing continues today.

QUESTION #2: What are the impacts to wildlife?

This question is difficult to answer as the Gulf of Mexico is a complex ecosystem with many different species — from bacteria, fish, oysters, to whales, turtles, and birds. While oil affected individuals of some fish in the lab, scientists have not found that the spill impacted whole fish populations or communities in the wild. Some fish species populations declined, but eventually rebounded. The oil spill did affect at least one non-fish population, resulting in a mass die-off of bottlenose dolphins. Scientists continue to study fish populations to determine the long term impact of the spill.

Question #3: What cleanup techniques were used, and how were they implemented?

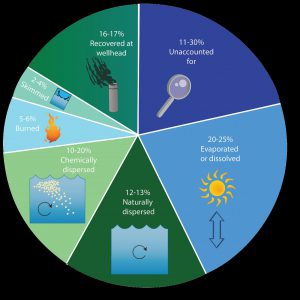

Several different methods were used to remove the oil. Offshore, oil was removed using skimmers, devices used for removing oil from the sea’s surface before it reaches the coastline. Controlled burns were also used, where surface oil was removed by surrounding it with fireproof booms and burning it. Chemical dispersants were used to break up the oil at the surface and below the surface. Shoreline cleanup on beaches involved sifting sand and removing tarballs and mats by hand.

QUESTION #4: Where did the oil go and where is it now?

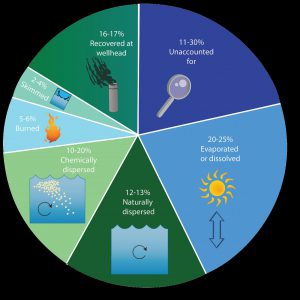

The oil spill covered 29,000 square miles, approximately 4.7% of the Gulf of Mexico’s surface. During and after the spill, oil mixed with Gulf of Mexico waters and made its way into some coastal and deep-sea sediments. Oil moved with the ocean currents along the coast of Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. Recent studies show that about 3-5% of the unaccounted oil has made its way onto the seafloor.

QUESTION #5: Do dispersants make it unsafe to swim in the water?

The dispersant used on the spill was a product called Corexit, with doctyl sodium sulfosuccinate (DOSS) as a primary ingredient. Corexit is a concern as exposure to high levels can cause respiratory problems and skin irritation. To evaluate the risk, scientists collected water from more than 26 sites. The highest level of DOSS detected was 425 times lower than the levels of DOSS known to cause harm to humans.

For additional information and publications related to the oil spill please visit: https://gulfseagrant.wordpress.com/oilspilloutreach/

Adapted From:

Maung-Douglass, E., Wilson, M., Graham, L., Hale, C., Sempier, S., and Swann, L. (2015). Oil Spill Science: Top 5 Frequently Asked Questions about the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. GOMSG-G-15-002.

An estimate of what happened to approximately 200 million gallons oil from the DWH oil spill. Data from Lehr, 2014. (Florida Sea Grant/Anna Hinkeldey)

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 22, 2016

Many folks are putting together a “bucket list” of things they would like to do or see before they can no longer do them. For many interested in natural resources there are certain national parks and scenic places they would like to visit. Other natural resource fans have a list of wildlife species they would like to see.

Terrapins inhabit creeks, such as this one, within the expanse of the salt marsh. Here you can see their heads pop up above the water and you may get lucky enough to find one basking.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Recently I hooked with famed Alabama outdoorsman Jimbo Meador to search for locations to find Alabama turtles. Jimbo has been fishing, hunting, and enjoying the Mobile Bay area all of his life and he now using that knowledge as a guide in a nature-based tourism project. He recently received a call from a group of gentleman from another part of the country who had on their bucket list viewing 1000 reptilian species in their native habitat. In Alabama they were interested in the Black-knobbed Map Turtle, the Alabama Red Belly, and the Diamondback Terrapin. Jimbo has just begun the first module of the Florida Master Naturalist Program and reached out to us for advice on where to find these guys. Luckily, after working with scientists from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, I knew where to find diamondback terrapins – and have a pretty good idea on the others.

These “diamonds of the marsh” – as they are sometimes called – are very elusive creatures. They inhabit muddy bottom creeks within extensive salt marsh habitat all along the Gulf and East coast of the United States. I spent two years searching the Florida panhandle before I found my first live animal. It was one of the odd things though – once you have seen one, you now know what you are looking for and begin to find more.

I took Jimbo to a location near Dauphin Island where about 150 terrapins are believed to exist. Terrapins spend most of their day within creeks that meander through acres of salt marsh. The odd thing is there may be hundreds of creeks within these marshes and the terrapins – for some reason – will select their favorites and hang there. You can spend all day paddling through perfect looking creeks not seeing a head at all… then all of sudden… you enter one creek… not really any different than the others… and there they are.

Veteran waterman and outdoor guide, Jimbo Meador, explores the marshes near Dauphin Island for the elusive diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Within these creeks they feed on a variety of shellfish but particularly like the marsh periwinkles. These small snails are the ones that climb the cordgrass and needlerush plants during high tide to avoid their nemesis the blue crab and the diamondback terrapin. Terrapins do crawl out of the water to bask in the sun and have been known to bury in the loose fine mud. Females must find high dry ground to lay her eggs. She may swim as far as 5 miles from her home creek to find a suitable beach. They do like sandy beaches that are open and free of most plants. They emerge onto these beaches during May and June to lay about 7-10 eggs. Most females will lay more than one clutch each season emerging once every 16 days or so. Different from sea turtles – terrapins nest during the daylight hours. Actually the sunnier – the better. Raccoons are a big problem… find and consuming the eggs; on some beaches researchers have reported 90% or more of the nest have been raided by the furry guys. Crows, snakes, and possibly armadillos will take nests as well. If the developing young survive the 60+ days of incubation, they will emerge and head for the grass areas of the marsh… not the water. Here they will spend the first year of their life living more like a land turtle before they make their way to the brackish waters of the salt marsh.

Open sandy beaches, such as the one in this photograph, are the spots females terrapins seek when they are ready to dig a nest.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

These are fascinating creatures and should be on everyone’s natural resource bucket list. The hard effort of finding them really makes doing so very rewarding. On this day Jimbo saw only one head – I did not see any. I have found in my study site that I see more heads in the afternoon (we were out in the morning). I do not know if this is the case at all terrapin nesting sites, but something to consider when looking. Though we did not find many that day he now knows what to look for when searching for them. Next we will have to hunt the Alabama Red Belly Turtle. That is another story for another day.

We will continue this series with other interesting wildlife creatures to “hunt” in the Florida panhandle.

by Carrie Stevenson | Feb 5, 2016

On “project day” students share their knowledge with the class. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is a 40-hour experiential learning course offered by UF IFAS Extension. While we spend time in class with presentations, by far everyone’s favorite aspects of the course are field trips and “project day.” As part of the course, each participant produces an educational tool—a display, presentation, skit, or lesson—that delves deeper into a topic of interest. The students and instructors are able to use these tools again and again to teach others.

Master Naturalist students walk “The Way” boardwalk in Perdido Key. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

One example of a multi-year student project is “The Way” nature trail, located at Perdido Bay United Methodist Church. Master Naturalist Jerry Patee worked with volunteers from his church and community to design and permit a boardwalk and nature trail leading to Bayou Garcon. The unique trail is less than a mile, but traverses upland, freshwater wetland, and coastal habitats, making it a perfect ecological teaching tool. The trail is open to the public and maintained as a place of quiet contemplation. The project is ongoing, with educational signage planned, but it is an excellent new resource for the community.

“The Way” is just one of many positive contributions made by Master Naturalist students over the years. To enroll in a Florida Master Naturalist course near you, visit the FMNP page or talk with an instructor at your local county Extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 5, 2016

Fishermen fish the marshes of Weeks Bay while a pelican looks on. Photo: WeeksBay.org

Mobile Bay?… part of the Florida panhandle?… Really?…

Well… yes… during the colonial period “West Florida” extended west to the Biloxi area and besides, all western panhandlers know we are really “lower Alabama”; we hear it a million times a year… so YES, it’s part of the Florida panhandle! We’ll go with it.

The shallow, muddy, and productive waters of Mobile Bay as they pass the port city of Mobile AL.

Photo: Auburn University

Approximately 35 miles long and 10 miles wide, Mobile Bay is one of the largest estuaries on the Gulf coast; draining close to 1/5th of the eastern United States. This wide, shallow, and muddy bay supports a variety of fresh and brackish water ecosystems. Wildlife from the Mississippi delta, the red hills of the Piedmont region, and the Florida panhandle all converge here making this one of the more biologically diverse areas in the country. It was home to both Dr. E.O. Wilson and Dr. Archie Carr who deeply loved the area and it has been a hub for estuarine research for decades. The rich abundance of wildlife supports commercial and recreational fishing and hunting as well as a growing ecotourism industry. Though the shallow bay must be dredged to support it, the Port of Mobile in one of the busiest in the Gulf region.

Weeks Bay is a small tributary to this bay system. Fed by the Fish and Magnolia Rivers on the southeastern shore of Mobile Bay, Weeks Bay discharges into Bon Secour, which supports a commercial fishing business. Lined with salt marshes, cypress swamps, and bogs, this area is great for wildlife viewing and fishing. It is also the area of Mobile Bay that experiences the famous crab jubilees; where levels of low dissolved oxygen on the bottom of the bay force benthic animals – such as crabs and flounder – to shallow water seeking oxygen. About 6,000 acres of this estuarine habitat is now part of NOAA’s National Estuarine Research Reserve system. At the reserve there are interactive exhibits, trails, and pontoon boat rides to explore and appreciate this special place.

Crab jubilees occur along the eastern shore of Mobile Bay during very warm summer evenings.

Photo: NOAA

What better place to learn about the estuaries of the Gulf coast! The Panhandle Outdoor LIVE program will conduct one of our four 2016 watershed schools at this reserve. We will have lectures on estuarine ecology, the seafood industry in Mobile Bay – highlighting oyster farming, and on the mission of the Research Reserve itself. We will also have a local outfitter lead a kayak/canoe trip through the estuary as well an interpretive nature hike at the reserve’s visitor center. It will be set up as an overnight trip for those traveling and we will be staying at Camp Beckwith, which on Weeks Bay. Registration for this trip will open at the end of February. If you have questions about this watershed school you can contact Carrie Stevenson or Rick O’Connor at (850) 475-5230; or Chris Verlinde at (850) 623-3868.

A relaxing spot at Camp Beckwith on Weeks Bay.

Photo: Camp Beckwith

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 2, 2015

They are marvelous creatures and there are very few panhandle residents who know what they are. My wife and I were introduced to Diamondback Terrapins by George Heinrich in 2005. George was the president of a nonprofit, Florida Turtle Conservation Trust, and a member of the Diamondback Terrapin Working Group, a national group of terrapin researchers and educators. He, and these organizations, were very interested in the status of terrapins in the Florida panhandle… so Molly and I took that job on.

Diamondback terrapins (Malaclemmys terrapin) are the only true brackish water resident turtle in the United States. They range from Cape Cod MA down the entire eastern seaboard, across the Gulf of Mexico to Brownsville TX. Within that range there are 7 described subspecies, 5 of those found in Florida, 2 found in the Florida panhandle. These estuarine turtles prefer salt marsh and mangrove habitat. They are very reclusive and difficult to find – hence why most locals have never seen nor heard of them. When I talk about them to the public I get responses such as… “do you mean tarpon?” “I find those in my yard all of the time” (probably a different species), “aren’t those from up north?” and “never heard of them”… they are not fish so they could be found in your yard if you live along the fringes of a salt marsh, they are up north – but they are here also.

Diamondback terrapin found in Wakulla County.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

In 2005 Molly and I were asked to survey the panhandle and determine if terrapin populations still exist. We decided to take that job on and then expand to determine their population size and whether those populations are increasing or decreasing. The coastal panhandle extends from Escambia County (on the Alabama state line) to Jefferson County (Aucilla River), but due to existing funding we could only survey to the Apalachicola River. This would include six counties: Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, and Gulf. We verified at least one record of a terrapin in each county. We discovered the larger the expanse of salt marsh – the higher probability of terrapins; thus those counties with relatively little salt marsh (such as Okaloosa) would have fewer/smaller terrapin populations.

But marsh alone is not enough. Terrapins need high ground in which to lay their eggs. High ground within a marsh is not a common thing. Research shows that terrapins will travel up to 5 miles in search of suitable nesting; which means a terrapin could be found in your neighborhood even if no marsh is visible. Unlike sea turtles they are “home-bodies” rarely leaving the marsh where they were born. They spend time forging for shellfish (particularly the snail called marsh periwinkle – Littorina irorata) and basking on and in the mud. They can be seen at the surface with their heads peering at you – they seem to be very curious.

Marsh periwinkles will climb cordgrass to avoid predation by blue crabs and terrapins.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Once we confirmed that terrapins were still in the panhandle we then began work on how many. To do this we needed to find their nesting beaches. Terrapin nesting season is about the same as that of sea turtles (May 1 – Aug 1); some nesting may occur after that but few. Unlike sea turtles they nest during daylight hours and prefer sunny days over cloudy/raining ones. They like to nest at high tide – thus finding a suitable location that is out of the way of potential flooding by the rising bay – however this does not account for severe storms. They typically lay about 10 eggs in their nest, cover and disguise, and then leave it to its fate. Unfortunately in many nesting areas, its fate is to be uncovered and consumed by predators – particularly raccoons. Molly and I would kayak salt marshes searching for suitable nesting beach. Once found, we would walk the beach looking for sign of nesting. If nesting was found this would be recorded and we would then begin 16-day monitoring trips. It is assumed that each sexually mature female within the population will nest once every 16 days; and they will nest more than once each year. Signs of nesting include tracks (which are counted), and egg shells from a nest that was raided by a raccoon (which were logged and removed). Occasionally we would come across a nesting female. We would allow her to complete the nesting activity and then capture her for measurements and photographs. We would mark her with a notch on the margin of the carapace (top shell) and release her (we did not have the funding for PIT tags). We would also set modified crab traps to capture them. Terrapins have a habitat of entering crab traps (probably more for the bait than the crabs) and becoming entrapped. Unless found within 15-30 minutes, they will drown. Our modified crab traps were tall enough that terrapins could reach the surface (even at the highest tide) and get a breath of air. We would set traps for 5 day periods and (if we caught any at all) would only capture during the first day or two. Terrapins are smart and we found that after day 2 most would approach our traps, observe our handy work, and swim away. With the data from these two activities we could get a rough idea of how many terrapins were in this population and how they changed over time.

The marshy habitat terrapins love.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

We focused our population surveys to our home counties of Santa Rosa and Escambia counties. We were able to identify 1 nesting beach in Escambia and 2 in Santa Rosa (we have since found a 3rd). We never caught a terrapin in Escambia but had good success at one of the two beaches in Santa Rosa. That population had approximately 50 individuals living within it. From 2007 to 2012 the population remained relatively stable. In 2012 I changed jobs and have not had a chance to re-survey. I plan to do this in 2016.

This year we trained 24 volunteers to assist us in locating and monitoring nesting beaches. They did find a new nesting beach in Santa Rosa and will begin monitoring nesting activity and trapping next year.

These are fascinating creatures and one of the most beautiful turtles you will ever see. Some have asked me about state protection for them. They are listed as a freshwater turtle with FWC thus you cannot possess more than two, cannot have any eggs, and cannot sell them.

If you have questions about diamondback terrapins, are interested in participating in terrapin surveys in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties, or would like to begin your own surveys in your county. Contact me (Rick O’Connor) at roc1@ufl.edu or (850) 475-5230.