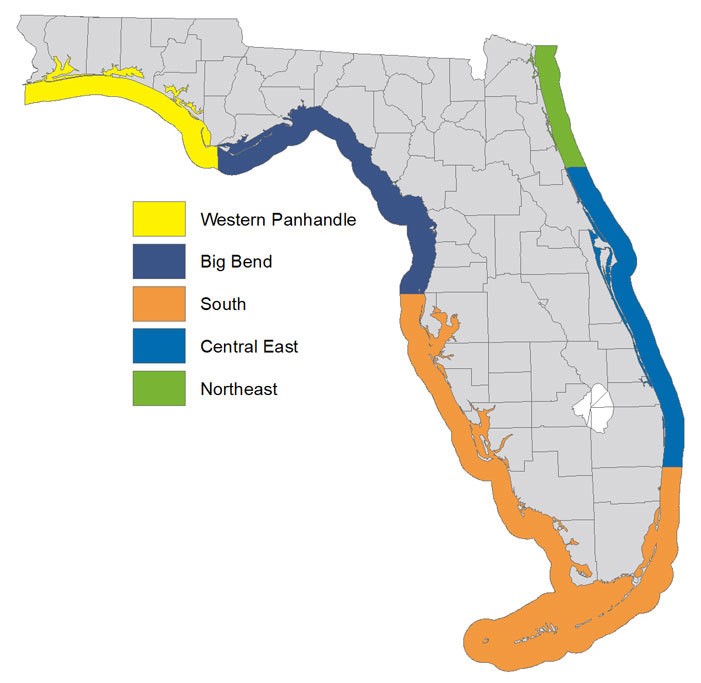

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2022

I am going to be honest and say that I know very little about this fish. I did not know they even existed until I attended college. Shortly afterwards, my father-in-law asked “hey, have you ever heard of a tilefish?” – to which I responded yes… He was having lunch at a restaurant in Apalachicola, and it was on the menu. My father-in-law was an avid fisherman and knew most of the edible species, but he had not heard of this one. The rumor was that it was pretty good, though my father-in-law chose not to eat it that day.

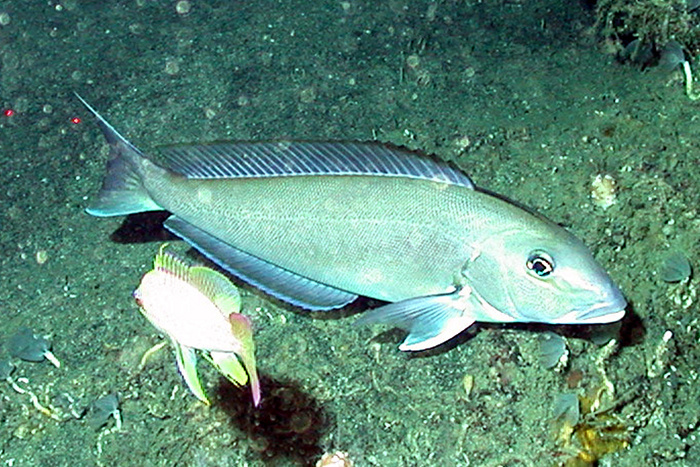

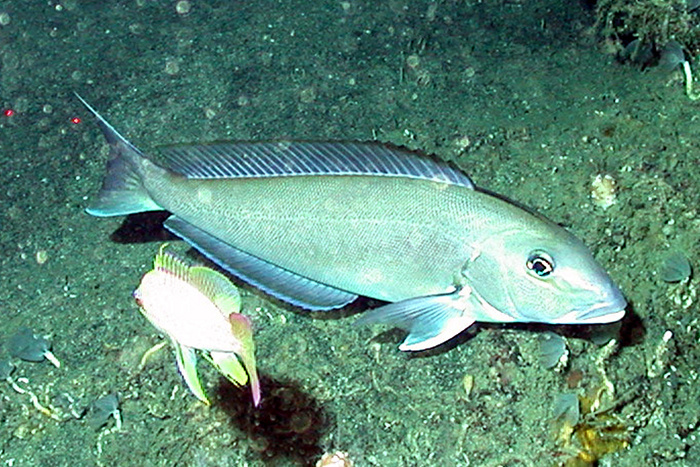

Tilefish

Photo: NOAA

I have never seen it on a menu, and only a few times in the local seafood markets, but according to Hoese and Moore1 by the late 1970s there was a small commercial fishery for this fish emerging in Louisiana, as was a small recreational fishery. In Florida, since 2000, there have been 15,435 commercial trips for this fish with an average of 321 each year. The value of this fishery over that time is $33,118,554 with an average of $689,969.90 each year. The average price for the fishermen was $2.62 per pound with the highest being $5.14/lb. on the east coast and that in 2022; the Gulf fishermen are getting $4.16/lb. right now.

The highest number of landings per county since 2000 was 340 in Palm Beach County in 2000. Only eight times has there been more than 200 landings in a single year over the last 22 years. Five of those were in Monroe County (Florida Keys) and three were again in Palm Beach County. The vast majority were less than 100 landings in a single year, this is not a large fishery in Florida either.

Are they harvested here in the Florida panhandle?

Yes… Bay, Escambia, Franklin, Okaloosa, Wakulla, and Gulf Counties all reported landings. Bay County seems to be the hot spot for panhandle with landings between 50-100 each year since 2000. Most of the other counties report less than 10 a year and several only reported one. Again, this is not a large fishery, but it was sold at a restaurant in Apalachicola and is said to be good. Hence, I decided to include in this series.

Hoese and Moore report four species of tilefish in the Gulf of Mexico. The sand tilefish (Malacanthus plumeri) is a more tropical species. The tilefish (Lopholatilus cheamaeleonticeps) and the gray tilefish (Caulalatilus microps) seem to be the target ones for fishermen. Both are reported from deep cold water near the edge of the continental shelf. FWC reports them from 250 – 1500 feet of water where the temperatures are between 50 – 60°F. Because of their tolerance to cold water, their geographic range is quite large; extending across the Gulf, up the east coast to Labrador. They live in burrows on hard sandy bottoms and feed on crustaceans. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration2 reports this as a slow growing – long lived fish, up to 50 years of age. In their cold environment, this makes sense.

This is not a well-known fish along the Florida Panhandle but maybe one day you will see it on the menu, remember this article, and take a chance to see if you like it.

References

1 Hoese, H.D., Moore, R.H. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press. College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Golden Tilefish. 2020. Species Directory. NOAA Fisheries. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/golden-tilefish.

by Kalyn Waters | May 20, 2021

There are several considerations to be taken in fishpond management. During the first of a three-part webinar series, Dr. Laura Tiu and Daniel Leonard talk about how to manage your pond to optimize its health.

There are several considerations to be taken in fishpond management. During the first of a three-part webinar series, Dr. Laura Tiu and Daniel Leonard talk about how to manage your pond to optimize its health.

Considerations on liming your pond, fertilizing your aquatic vegetation and how to manage dissolved oxygen are topics address in this recording.

The webinar in its entirety can be viewed at: Fish Camp: Pond Health

One of the recommended methods of tracking the health of your pond is enjoyable! As a pond manager you should be gathering simple information about the fish you catch. By tracking the fish that you catch, you can look at presence, size distribution and relative abundance of adult fish populations, which is directly linked to the health of your body of water.

When logging your catch, the following should be considered:

- Date – You will want to evaluate the catches from the same time of year over several years

- Weight- not only is the length of the fish important but also collect the weight

- Type/Species of each fish caught and approximate maturity of that fish

By logging your catches over the years, you will begin to see trends and have more information to make pond management decisions. More helpful information can be found at:

How to Survey the Fish in Your Pond

How to Assess the Fish in Your Farm Pond

by Mark Mauldin | Apr 9, 2021

Spring can be a busy time of year for those of us who are interested in improving wildlife habitat on the property we own/manage. Spring is when we start many efforts that will pay-off in the fall. If you are a weekend warrior land manager like me there is always more to do than there are available Saturdays to get it done. The following comments are simple reminders about some habitat management activities that should be moving to the top of your to-do list this time of year.

Aquatic Weed Management – If you had problematic weeds in you pond last summer, chances are you will have them again this summer. NOW (spring) is the time to start controlling aquatic weeds. The later into the summer you wait the worse the weeds will get and the more difficult they will be to control. The risk of a fish-kill associated with aquatic weed control also increases as water temperatures and the total biomass of the weeds go up. Springtime is “Just Right” for Using Aquatic Herbicides

Cogongrass Control – Spring is actually the second-best time of year to treat cogongrass, fall (late September until first frost) is the BEST time. That said, ideally cogongrass will be treated with herbicide every six months, making spring and fall important. When treating spring regrowth make sure that there are green leaves at least one foot long before spraying. Spring is also an excellent time of year to identify cogongrass patches – the cottony, white blooms are easy to spot. Identify Cogongrass Now – Look for the Seedheads; Cogongrass – Now is the Best Time to Start Control

Cogongrass seedheads are easily spotted this time of year.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Warm-Season Food Pots – There is a great deal of variation in when warm season food plots can be planted. Assuming warm-season plots will be panted in the same areas as cool-season plots, the simplest timing strategy is to simply wait for the cool-season plots to play out (a warm, dry May is normally the end of even the best cool-season plot) and then begin preparation for the warm-season plots. This transition period is the best time to deal with soil pH issues (get a soil test) and control weeds. Seed for many varieties of warm-season legumes (which should be the bulk of your plantings) can be somewhat hard to find, so start looking now. If you start early you can find what you want, and not just take whatever the feed store has. Warm Season Food Plots for White-tailed Deer

Deer Feeders – Per FWC regulations deer feeders need to be in continual operation for at least six months prior to hunting over them. Archery season in the Panhandle will start in mid-October, meaning deer feeders need to be up and running by mid-April to be legal to hunt opening morning. If you have plans to move or add feeders to your property, you’d better get to it pretty soon. FWC Feeding Game

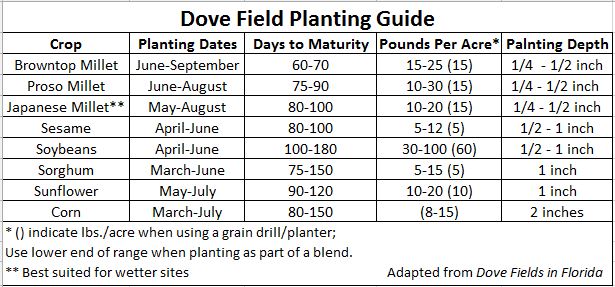

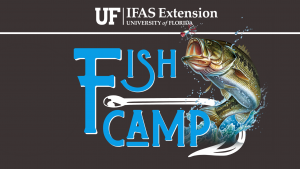

Dove Fields – The first phase of dove season will begin in late September. When you look at the “days to maturity” for the various crops in the chart below you might feel like you’ve got plenty of time. While that may be true, don’t forget that not only do you need time for the crop to mature, but also for seeds to begin to drop and birds to find them all before the first phase begins. Because doves are particularly fond of feeding on clean ground, controlling weeds is a worthwhile endeavor. If you are planting on “new ground”, applying a non-selective herbicide several weeks before you begin tillage is an important first step to a clean field, but it adds more time to the process. As mentioned above, it’s always pertinent to start sourcing seed well in advance of your desired planting date. Timing is Crucial for Successful Dove Fields

There are many other projects that may be more time sensitive than the ones listed above. These were just a few that have snuck up on me over the years. The links in each section will provide more detailed information on the topics. If you have questions about anything addressed in the article feel free to contact me or your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Natural Resource Agent.

by Erik Lovestrand | Mar 11, 2021

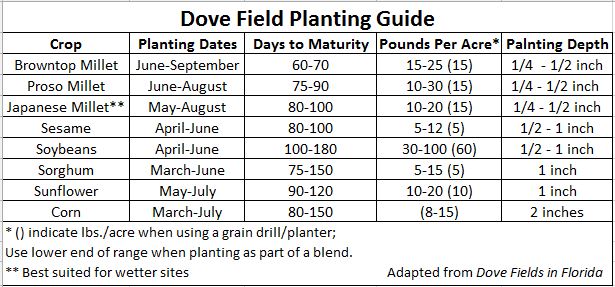

Cobia Researchers use Transmitters as well as Tags to Gather Data on Migratory Patterns

I must admit to having very limited personal experience with Cobia, having caught one sub-legal fish to-date. However, that does not diminish my fascination with the fish, particularly since I ran across a 2019 report from the Gulf States Marine Fisheries Commission titled “Management Profile for Gulf of Mexico Cobia.” This 182-page report is definitely not a quick read and I have thus far only scratched the surface by digging into a few chapters that caught my interest. Nevertheless, it is so full of detailed life history, biology and everything else “Cobia” that it is definitely worth a look. This posting will highlight some of the fascinating aspects of Cobia and why the species is so highly prized by so many people.

Cobia (Rachycentron canadum) are the sole species in the fish family Rachycentridae. They occur worldwide in most tropical and subtropical oceans but in Florida waters, we actually have two different groups. The Atlantic stock ranges along the Eastern U.S. from Florida to New York and the Gulf stock ranges From Florida to Texas. The Florida Keys appear to be a mixing zone of sorts where Cobia from both stocks go in the winter. As waters warm in the spring, these fish head northward up the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of Florida. The Northern Gulf coast is especially important as a spawning ground for the Gulf stock. There may even be some sub-populations within the Gulf stock, as tagged fish from the Texas coast were rarely caught going eastward. There also appears to be a group that overwinters in the offshore waters of the Northern Gulf, not making the annual trip to the Keys. My brief summary here regarding seasonal movement is most assuredly an over-simplification and scientists agree more recapture data is needed to understand various Cobia stock movements and boundaries.

Worldwide, the practice of Cobia aquaculture has exploded since the early 2000’s, with China taking the lead on production. Most operations complete their grow-out to market size in ponds or pens in nearshore waters. Due to their incredible growth rate, Cobia are an exceptional candidate for aquaculture. In the wild, fish can reach weights of 17 pounds and lengths of 23 inches in their first year. Aquaculture-raised fish tend to be shorter but heavier, comparatively. The U.S. is currently exploring rules for offshore aquaculture practices and cobia is a prime candidate for establishing this industry domestically.

Spawning takes place in the Northern Gulf from April through September. Male Cobia will reach sexual maturity at an amazing 1-2 years and females within 2-3 years. At maturity, they are able to spawn every 4-6 days throughout the spawning season. This prolific nature supports an average annual commercial harvest in the Gulf and East Florida of around 160,000 pounds. This is dwarfed by the recreational fishery, with 500,000 to 1,000,000 pounds harvested annually from the same region.

One of the Cobia’s unique features is that they are strongly attracted to structure, even if it is mobile. They are known to shadow large rays, sharks, whales, tarpon, and even sea turtles. This habit also makes them vulnerable to being caught around human-made FADs (Fish Aggregating Devices). Most large Cobia tournaments have banned the use of FADs during their events to recapture a more sporting aspect of Cobia fishing.

To wrap this up I’ll briefly recount an exciting, non-fish-catching, Cobia experience. My son and I were in about 35 feet of water off the Wakulla County coastline fishing near an old wreck. Nothing much was happening when I noticed a short fin breaking the water briefly, about 20 yards behind a bobber we had cast out with a dead pinfish under it. I had not seen this before and was unaware of what was about to happen. When the fish ate that bait and came tight on the line the rod luckily hung up on something in the bottom of the boat. As the reel’s drag system screamed, a Cobia that I gauged to be 4-5 feet long jumped clear out of the water about 40 yards from us. Needless to say, by the time we gained control of the rod it was too late; a heartbreaking missed opportunity. Every time we have been fishing since then, I just can’t stop looking for that short, pointed fin slicing towards one of our baits.

by Mark Mauldin | Feb 5, 2021

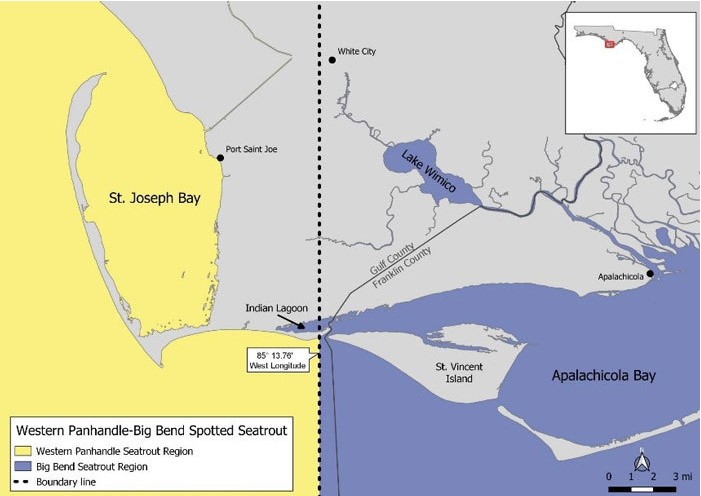

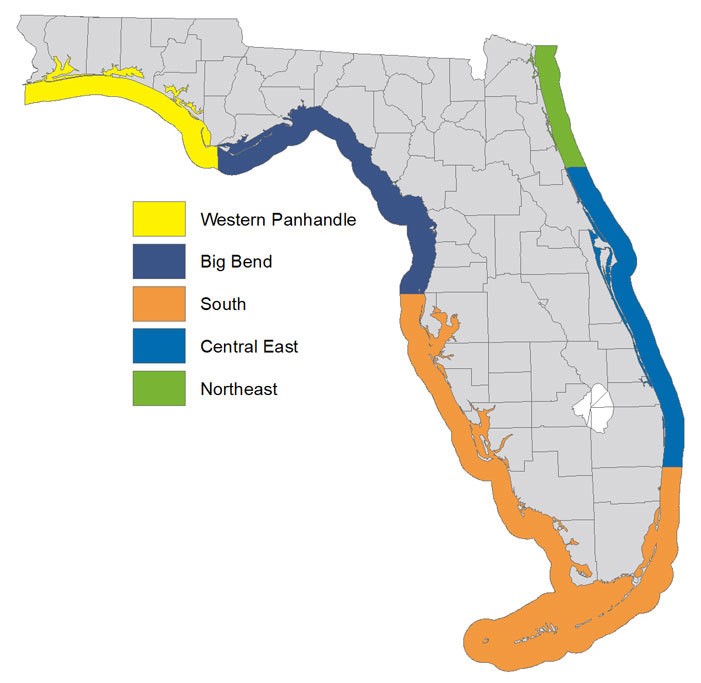

Reminder: Spotted seatrout harvest is closed in the Western Panhandle Management Zone the entire month of February.

New regulations were put into place last year reducing bag limits and closing harvest during February in the Western Panhandle Management Zone. For more details see my previous post on the subject.When Spotted Seatrout season is open (months other than February) in the Western Panhandle Management Zone the daily bag limit is 3 per harvester. Harvested Spotted Seatrout must be more than 15 inches long and less than 19 inches long. One fish, per vessel, over 19 inches my be included in the bag limit.

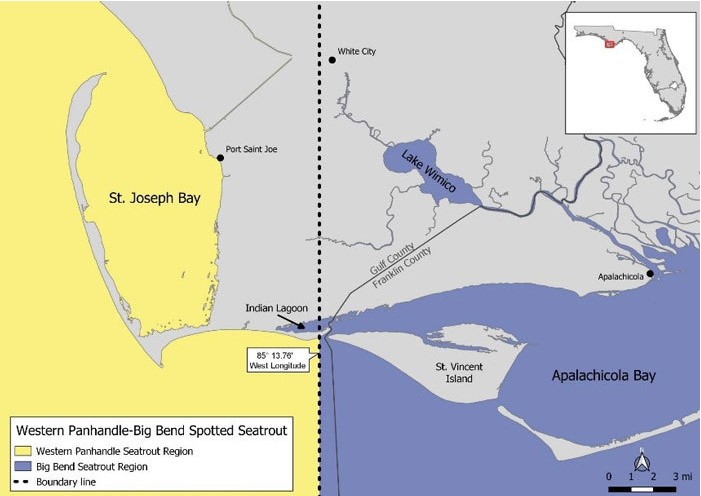

The Western Panhandle Spotted Seatrout Management Zone includes the State and federal waters of Escambia County through the portions of Gulf County west of longitude 85 degrees, 13.76 minutes but NOT including Indian Pass/Indian Lagoon.

Boundary between the Western Panhandle and Big Bend spotted seatrout management zones.

Image source: www.myfwc.com

See myfwc.com for complete information on all game and fish regulations in Florida.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 16, 2020

When most people think of reefs, they think of the coral reefs of the Florida Keys and Australia. But here in the northern Gulf the winters are too cold for many species of corals to survive. Some can, but most cannot and so we do not have the same type of reefs here.

That said, we do have reefs. We have both natural and artificial reefs. There are natural reefs off Destin and a large reef system off the coast of Texas – known as the “Flower Gardens”. Here the water temperatures on the bottom are warm enough to support some corals. The artificial reef program along the northern Gulf is one of the more extensive ones found anywhere. There is a science to designing an artificial reef – you do not just go out and dump whatever – because if not designed correctly, you will not get the fish assemblages and abundance you were hoping for. But if you do… they will come.

Reefs are known for their high diversity and abundance of all sorts of marine life – including fishes. There are numerous places to hide and plenty of food. Most of the fish living on the reef are shaped so they can easily slide in and out of the structure, have teeth that can crush shell – the parrotfish can actually crush and consume the coral itself, and some can be fiercely territorial. There are numerous tropical species that can be found on them and they support a large recreational diving industry. Let’s look at a few of these reef fish.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray Eels

These are fish of legend. There all sorts of stories of large morays, with needle shaped teeth, attacking divers. Some can get quite large – the green moray can reach 8-9 feet and weigh over 50 pounds. Though this species is more common in the tropics, it has been reported from some offshore reefs in the northern Gulf. There are three species that reside in our area: the purplemouth, the spotted, and the ocellated morays. The local ones are in the 2-3 foot range and have a feisty attitude – handle with care – better yet… don’t handle. They hide in crevices within the reef and explode on passing prey, snagging them with their sharp teeth. Many divers encounter them while searching these same crevices for spiny lobster. There are probing sticks you can use so that you do not have to stick your hand in there. There are rumors that since they have sharp teeth and tend to bite, they are venomous – this is not the case, but the bite can be painful.

The massive size of a goliath grouper. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

Groupers

This word is usually followed by the word “sandwich”. One of the more popular food fish, groupers are sought by anglers and spearfishermen alike. They are members of the serranid family (“sea basses”). This is one of the largest families of fishes in the Gulf – with 34 species listed. 15 of these are called “grouper” and there have been other members of this family sold as “grouper”.

So, what is – or is not – a “grouper”. One method used is anything in the genus Epinephelus would be a grouper. This would include 11 species, but would leave out the Comb, Gag, Scamp, Yellowfin, and Black groupers – which everyone considers “grouper”. Tough call eh?

These are large bodied fish with broad round fins – the stuff of slowness. That said, they can explode, just like morays, on their prey. Anglers who get a grouper hit know it, and divers who spear one know it. They range in size from six inches to six feet. The big boy of the group is the Goliath Grouper (six feet and 700 pounds). They love structure – so natural and artificial reefs make good homes for them. They also like the oil rigs of the western Gulf.

An interesting thing about many serranids is the fact they are hermaphroditic – male and female at the same time. Most grouper take it a step further – they begin life as females and become males over time.

The king of finfish… the red snapper

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Snappers

The red snapper is king. Prized as a food fish all over the United States, and beyond, these fish have made commercial fishermen very happy. With an average length of 2.5 feet, some much larger individuals have been landed. This fishery put Pensacola on the map in the early 20th century. Sailing vessels called “Snapper Smacks” would head out to the offshore banks and natural reefs, return with a load, and sell both locally and markets in New York. There are large populations in Texas waters and down on the Campeche Banks off Mexico. “Snapper Season” is a big deal around here.

Though these are reef fish, snapper have a habit of feeding above, and away from, them. You probably knew there was more than one kind of snapper but may not know there are 10 species locally. Due to harvesting pressure, there are short seasons on the famous red snapper – so vermillion snapper has stepped in as a popular commercial fishery – and it is very good also. Some, like the gray snapper, are more common inshore around jetties and seawalls. Also known as the black snapper or mangrove snapper, this fish can reach about three feet in length and make a good meal as well.

The white grunt.

Photo: University of Florida

Grunts

Grunts look just like snapper, and probably sold as them somewhere. But they are a different family. They lack the canines and vomerine teeth the snappers have – other than that, they do look like snapper. Easy to tell apart right? Vomerine are tiny teeth found in the roof of the mouth, in snappers they are in the shape of an arrow. They get their name from a grunting sound they make when grinding their pharyngeal teeth together. A common inshore one is called the “pigfish” because of this. They do not get as large as snapper (most are about a foot long) and are not as popular as a food fish, but the 11 known species are quite common on the reefs, and the porkfish is one of the more beautiful fish you will see there.

Spadefish on a panhandle snorkel reef.

Photo: Navarre Beach Snorkel

Spadefish

This is one of the more common fish found around our reefs. Resembling an angelfish, they are often confused with them – but they are in a family all to themselves. What is the difference you ask? The dorsal fin of the spade fish is divided into two parts – one spiny, the other more fin-like. In the angelfish, there is only one continuous dorsal fin.

Spadefish like to school and are actually good to eat. It is also the logo/mascot of the nearby Dauphin Island Sea Lab.

Gray triggerfish.

Photo: NOAA

Triggerfish

“Danger Will Robinson!” This fish has a serious set of teeth and will come off the reef and bite through a quarter inch wetsuit to defend their eggs. Believe it – they are not messing around. Once considered a by-catch to snapper fishermen, they are now a prized food fish. They are often called “leatherjackets” due to their fused scales forming a leathery like skin that must be cut off – no scaling with this fish. They have the typical tall-flat body of a reef fish, squeezing through the rocks and structure to hide or hunt. We have five species listed in the Gulf of Mexico, but it is the Gray Triggerfish that is most often encountered.

Photo courtesy of Florida Sea Grant

Lionfish

You may, may not, have heard of this one – most have by now. It is an invader to our reefs. To be an invasive species you must #1 be non-native. The lionfish is. There are actually about 20 species of lionfish inhabiting either the Indo-Pacific or the Red Sea region.

#2 have been brought here by humans (either intentionally or unintentionally – but they did not make it on their own) – this is the case with the lionfish. It was brought here for the aquarium trade. There are actually two species brought here: The Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans) and the Devilfish (Pterois miles). Over 95% of what has been captured are the red lionfish – but it really does not matter, they look and act the same – so they are just called “lionfish”.

#3 they must be causing an environmental, and/or an economic problem. Lionfish are. They have a high reproductive rate – an average of 30,000 offspring every four days. There is science that during sometimes of the year it could be higher, also they breed year-round. Being an invasive species, there are few predators and so the developing young (encapsulated in a gelatinous sac) drift with the currents to settle on new reefs where they will eat just about anything they can get into their mouths. There have been no fewer than 70 species of small reef fish they have consumed – including the commercially valuable vermillion snapper and spiny lobster. There is now evidence they are eating other lionfish.

They quickly take over a reef area and some of the highest densities in the south Atlantic region have been reported off Pensacola. However, at a 2018 state summit, researchers indicated that the densities in our area have declined in waters less than 200 feet. This is most probably due to the harvesting efforts we have put on them. They are edible – actually, quite good, and there is a fishery for them. Derbies and ecotours have been out spearfishing for them since 2010. You may have heard they were poisonous and dangerous to eat. Actually, they are venomous, and the flesh is fine. The venom is found in the spines of the dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins. It is very painful, but there are no records of anyone dying from it. Work and research on management methods continue.