by Laura Tiu | Mar 7, 2025

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.

If you’re wondering how to get your pond ready for spring, here are some key considerations and resources to help guide you.

Start with a Water Quality Test

The first step in assessing your pond’s health is testing the water. I always recommend that pond owners bring a pint-sized water sample in a clean jar to their local Extension Office for analysis. Keep in mind that not all offices offer this service, and public testing options are limited. However, private labs and DIY testing kits are available—though they can be costly.

The most important parameters to check are pH, alkalinity, and hardness: pH should ideally range between 6 and 9 for a healthy fish population. Local ponds often hover around 6.5, making them slightly acidic.

Alkalinity and hardness measure the water’s ability to neutralize acids and buffer against sudden pH changes. For optimal pond health, alkalinity should be at least 20 mg/L, but many local ponds fall below this level.

Improving Pond Water Quality

If your pond’s water quality is less than ideal, there are two common ways to improve it: liming and fertilization.

Applying Agricultural Lime: Properly adding agricultural lime can raise alkalinity and stabilize pH levels. However, in high-flow ponds, lime tends to wash away quickly, making this method ineffective for ponds with constant discharge.

Fertilizing to Boost Productivity: Fertilization increases phytoplankton growth, which supports the pond’s entire food web, benefiting juvenile fish and invertebrates. Unfortunately, like lime, fertilizer is quickly washed out of high-flow ponds, making it ineffective in these cases.

Making the Best of Your Pond

If your pond has a continuous discharge due to spring flow, the best approach may be to embrace its natural clarity, even if it doesn’t support a thriving fish population. However, if your pond retains water without frequent outflow, you may be able to enhance its productivity with the right amendments.

For personalized guidance, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. You can also start by reviewing this helpful fact sheet: Managing Florida Ponds for Fishing. By understanding your pond’s unique characteristics, you can make informed decisions to keep it healthy and enjoyable throughout the season.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jan 17, 2025

Over the last 10 years or so, the Florida Panhandle has gotten used to relatively warm winters, at least historically speaking. While we have experienced sharp cold snaps that were devastating to unprepared landscapes and gardens (the most recent being the late December dip down into the low to mid-teens in 2022), they haven’t lasted long and, overall, winters have been mild. Anecdotally, it seems like this winter (2024-2025) has been a return to a historical norm, with extended periods of cloudy, dreary cold; but does the data support that feeling? Let’s find out.

There are several ways of measuring the relative cold of one winter to the next. You could use weather station data and see what the coldest temperatures a given year received. You could track how many days the mercury dipped below freezing. You could measure the maximum temperatures and compare those year to year. However, for gardeners, commercial crop growers, and most other people, I think the most useful and intuitive comparison of winter intensity from year to year is chill hours.

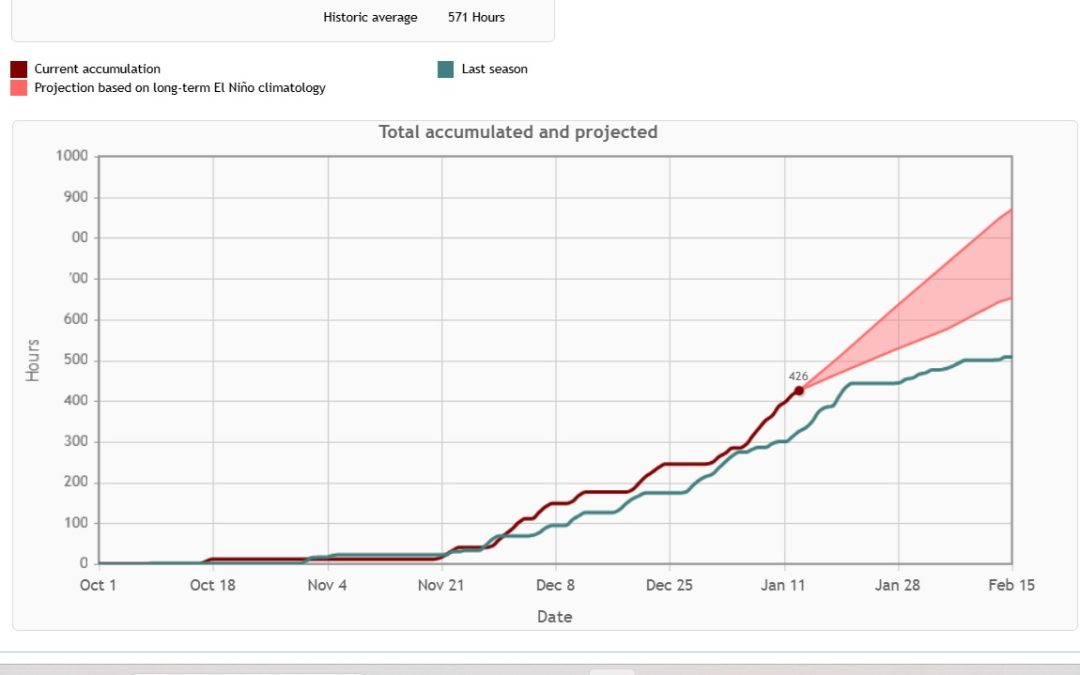

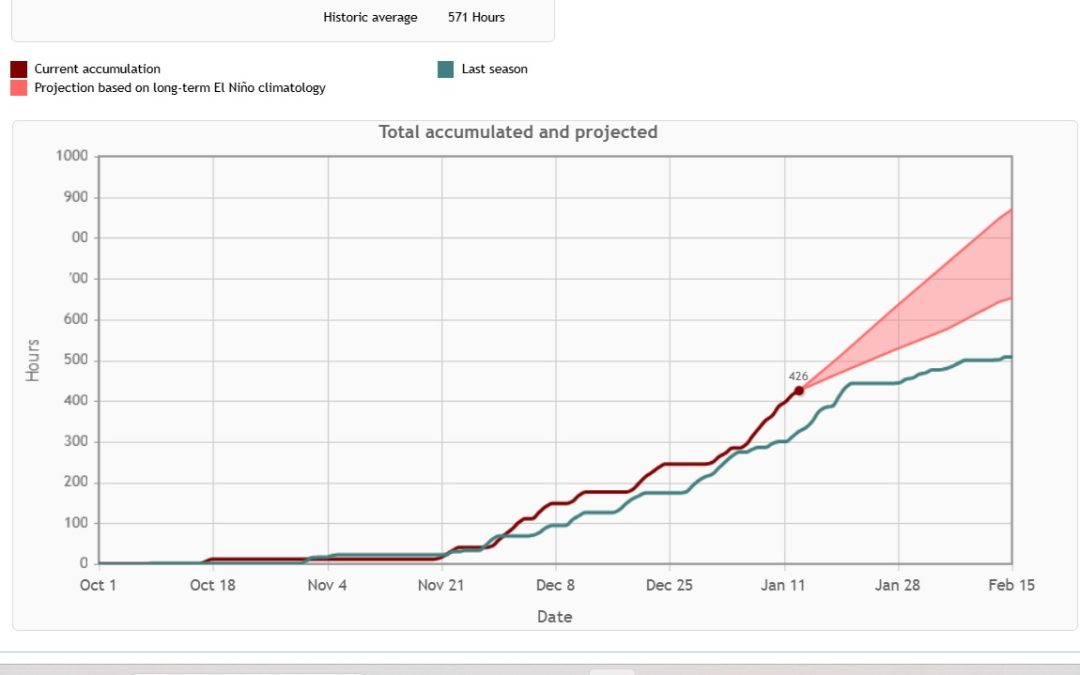

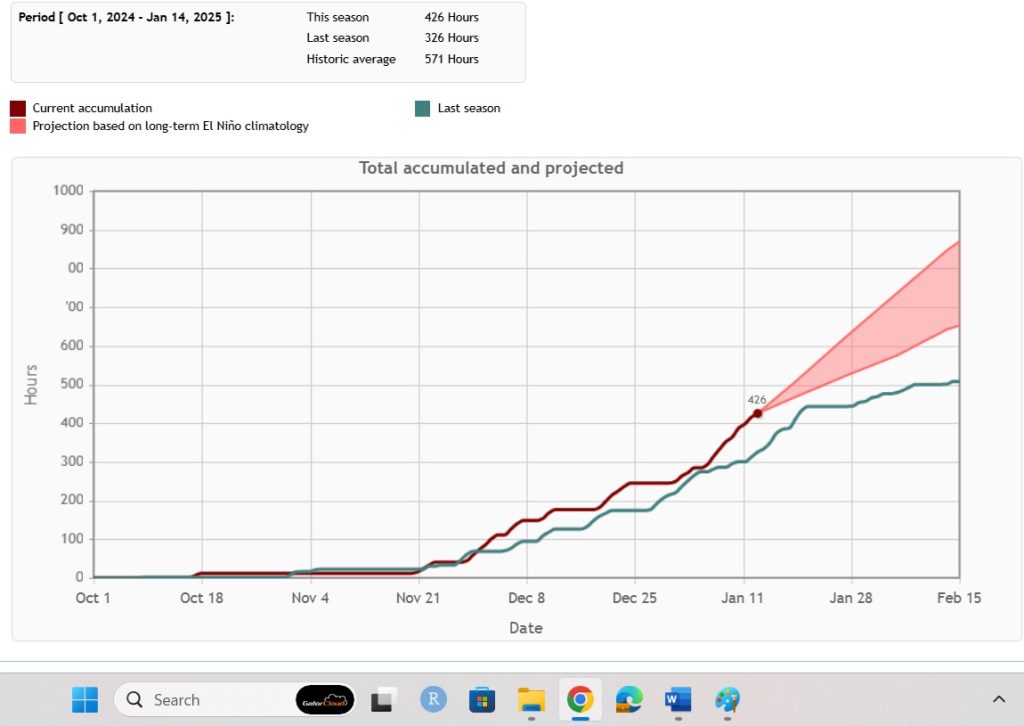

A chill hour is loosely defined as an hour below 45 degrees. Chill hours play a big role in deciduous fruiting plants flowering cycle and ultimately help determine if those plants make fruit the following year or not. While that is important to fruit growers, in this article, we’re more concerned with using chill as a relative comparison of winter intensity year to year. Last winter, the Florida Automated Weather Network (FAWN) station in Marianna (the closest one to Calhoun County that observes chill hours) logged 326 hours from the period of October 1 to January 14. This winter, that same weather station has logged 426 hours in the same period of time. A little elementary school math tell us we’ve received 100 more chill hours *so far* this year than we received last year – the equivalent of four entire 24 hour days under 45 degrees! That’s pretty significant. However, the historical average over the same time period is 571 chill hours, so we are still lagging behind what the area “used” to receive.

So yes, this winter has been colder than last at the time of this writing (January 16) and that isn’t even considering the extreme cold forecast for next week (week of January 20th) when you’re likely to be reading this. Things have been cold and are likely to remain that way for at least the rest of January, maybe beyond into February. However, it is important to remember that this year isn’t an outlier historically, as even this spat of recent cold finds us lagging our historical cold temperature norms a bit.

To track chill hours yourself, visit this website. For more information on our local natural resources and climate, contact your local Extension office. Bundle up out there an enjoy the coldest winter in several years!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Dec 20, 2024

The Panhandle isn’t known for its fall foliage. The best we can normally hope for are splashes of pale yellow amidst a sea of green pine needles, drab brown leaves killed by the first frost, and invasive Chinese Tallow trees taunting us with vibrant colors we know we shouldn’t have. However, in 2024, you’d be forgiven if you forgot you were in Florida and had instead been transported to a more northern clime where leaves everywhere turned brilliant shades of yellow, orange, purple, and red. I’ve heard comments from many folks, and I agree, that this is the best fall color we’ve seen here in a long time – maybe ever. So, why were the leaves so pretty this year? Let’s dive in.

Bald Cypress displaying brilliant burnt orange foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

What causes leaves to change colors in the fall?

First, what makes leaves of deciduous trees/shrubs (plants that shed their leaves in the winter) change color in the first place? The primary driver of leaf color change is daylength. During the summer, leaves appear green due to the presence of chlorophyll, which reflects green light, absorbs red and blue light, and is responsible for photosynthesis. When days shorten in the fall, plants sense that winter is coming and produce hormones that signal leaves to shut down chlorophyll production. They then initiate construction of a “wall” of cells that seals leaves off from the rest of the plant. When this happens, existing chlorophyll is “used up”, sugars build up in the now sealed off leaves, and other compounds that give leaves color, anthocyanins and carotenoids, take center stage. These compounds allow leaves to exhibit the familiar autumnal hues of yellow, red, orange, purple, and brown. However, plants go through this physiological process of shutting down growth and shedding leaves every year and excellent fall color, like what we experienced this year, doesn’t always result. There has to be more to the fall 2024 story.

Why were leaves so pretty this year?

Shumard Oak exhibiting outstanding red fall foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

A second factor is required for a great fall foliage show – weather. According to the U.S. Forest Service, ideal temperature and moisture conditions must be met for leaf color to be its most intense. Ideal autumn conditions include warm (but not hot) sunny days with cool (but not freezing) nights and adequate (but not excessive) moisture. Too hot and plants become stressed, lessening fall color potential. Too cold, and frost can kill foliage – turning it immediately brown and preventing color development. Too rainy or windy, and leaves can be blown off prematurely. 2024 brought neither extremely hot, extremely cold, or extremely wet conditions, and we were blessed to experience a Goldilocks fall color season.

Did Some Trees Have Better Color than Others?

While pretty much all deciduous trees exhibited their peak color potential this year, there were definitely standouts! Fortunately, many of the prettiest trees this fall also make outstanding landscape trees. Be on the lookout for the following trees in nurseries this winter and consider adding a few to your yard to take advantage of the next Goldilocks fall color year:

- Red Maple (Acer rubrum) – brilliant red fall leaves.

- Florida Maple (Acer floridanum) – yellow/orange.

- Deciduous Oaks (Quercus spp) – generally red to purple. Some species like Sawtooth Oak ( acutissima) are yellow.

- Green Ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica) – yellow.

- Swamp Tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) – crimson to purple.

- Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) – highly variable but generally reds, oranges, and purples.

- Bald Cypress (Taxodium distichum) – burnt orange.

For more information about fall color, which trees and shrubs produce great fall color and perform well in landscapes, or any other horticultural topic, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension office. Happy Gardening!

by Ray Bodrey | Nov 21, 2024

Recently Jennifer Bearden, our Agriculture & Natural Resource Agent in Okaloosa County wrote a great article on “Common Wildlife Food Plot Mistakes”. The following information is a mere supplement in establishing food plots. Planting wildlife forages has become a great interest in the Panhandle. North Florida does have its challenges with sandy soils and seasonal patterns of lengthy drought and heavy rainfall. With that said, varieties developed and adapted for our growing conditions are recommended. Forage blends are greatly suggested to increase longevity and sustainability of crops that will provide nutrition for many different species.

Hairy Vetch – Ray Bodrey

In order to be successful and have productive wildlife plots. It is recommended that you have your plot’s soil tested and apply fertilizer and lime according to soil test recommendations. Being six weeks from optimal planting, there’s no time like the present.

Below are some suggested cool season wildlife forage crops from UF/IFAS Extension. Please see the UF/IFAS EDIS publication, “A Walk on the Wild Side: 2024 Cool-Season Forage Recommendations for Wildlife Food Plots in North Florida” for specific varieties, blends and planting information. https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG13900.pdf

Winter legumes are more productive and dependable in the heavier clay soils of northwest Florida or in sandy soils that are underlain by a clay layer than in deep upland sands or sandy flatwoods. Over seeded white clover and ryegrass can grow successfully on certain flatwoods areas in northeast Florida. Alfalfa, clovers, vetch and winter pea are options of winter legumes.

Cool-season grasses generally include ryegrass and the small grains: wheat, oats, rye, and triticale (a human-made cross of wheat and rye). These grasses provide excellent winter forage and a spring seed crop which wildlife readily utilize

Brassica and forage chicory are annual crops that are highly productive and digestible and can provide forage as quickly as 40 days after seeding, depending on the species. Forage brassica crops such as turnip, swede, rape, kale and radish can be both fall- and spring-seeded. Little is known about the adaptability of forage brassicas to Florida or their acceptability as a food source for wildlife.

Deer taking advantage of a well maintained food plot. Photo: Mark Mauldin

For more information, contact your local county extension office.

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Thomas Derbes II | Nov 8, 2024

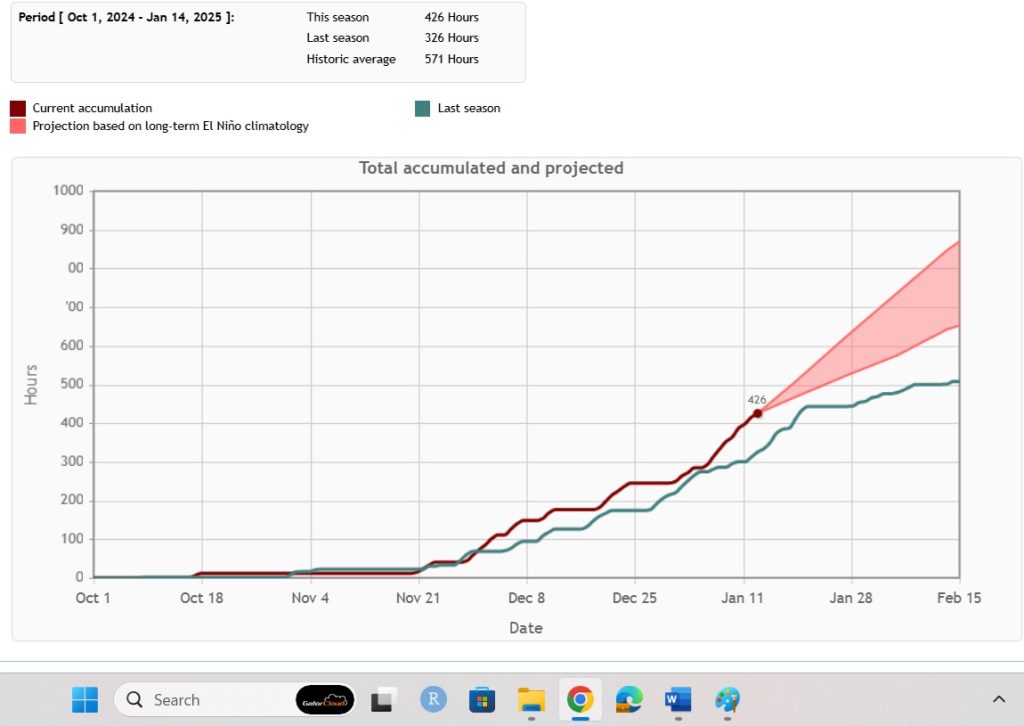

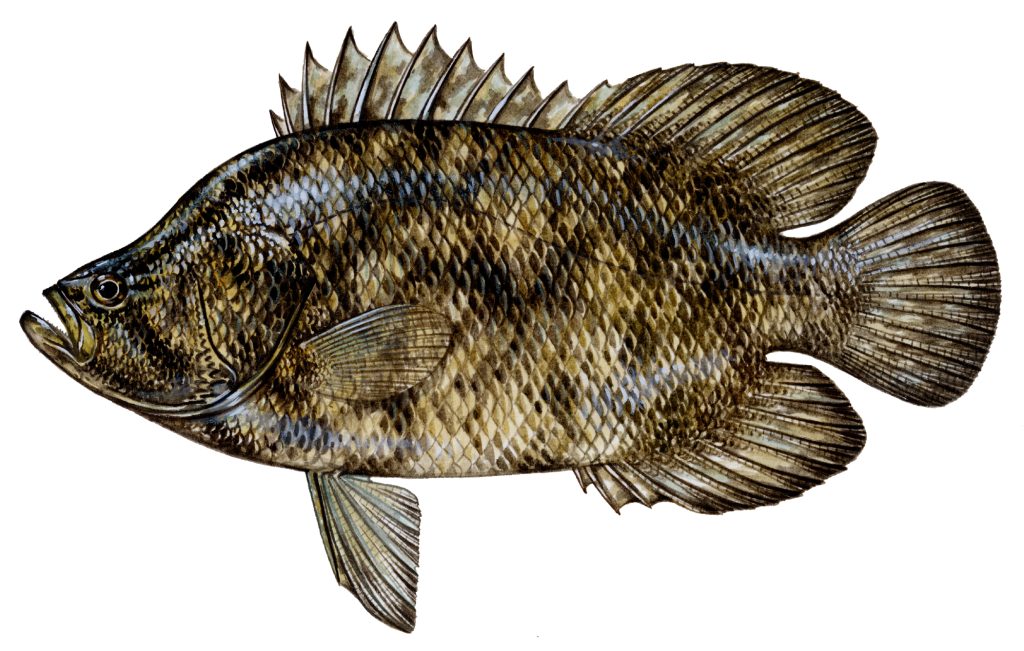

The Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) is a very prized sportfish along the Florida Panhandle. Typically caught as a “bonus” fish found along floating debris, the tripletail is a hard fighting fish and excellent table fare. Just as the name implies, this fish is equipped with three “tails” that help aid it in propulsion; and also help contribute to their strong fighting spirit. In addition to the caudal fin, tripletail have very pronounced “lobed” dorsal and anal fin soft rays that sit very far back on the body, giving it the appearance of three tails (triple-tails).

Atlantic Tripletail (Lobotes surinamensis) – FWC, Diane Rome Peebles 1992

Tripletail are found in tropical and subtropical seas around the world (except the eastern Pacific Ocean) and are the only member of their family found in the Gulf of Mexico. Tripletail can be found in all saltwater environments, from the upper bays to the middle of the Gulf of Mexico. In the Florida Panhandle, tripletail begin to show up in the bays beginning in May and can be found up until October/November. They are masters of disguise, usually found floating along floating debris, crab trap buoys, navigation pilings, and floating algae like Sargassum. When tripletail are young, they are able to change their colors to match the debris, albeit it is usually a variation of yellow, brown, and black. Adult tripletail can change color as well, but the coloration is not as vibrant as the juveniles. Floating alongside debris and other floating materials protects them from predators and gives them food access. Small crustaceans, like shrimp and crabs, and small fish will gather along the floating debris, looking for protection, giving the camouflaged tripletail an easy meal.

Baby Tripletail or Leaf? – Thomas Derbes II

Tripletail are opportunistic feeders that are what I classify as “lazy hunters.” Tripletail will hang out along any floating debris and wait for the food to come to them. They typically will not chase their prey items too far and will abandon the hunt if they expend too much energy. Since they are opportunistic feeders, their diet varies widely, but they cannot resist a baby blue crab, shrimp, or small baitfish like menhaden (Brevoortia patronus) that might visit their floating oasis. When further offshore, it is not uncommon to find many tripletail “laying out” on sargassum or floating debris. I personally have seen a dozen full-sized tripletail inside of a large traffic barrel 25 miles offshore that saved a skunk of a deep-dropping fishing trip.

Tripletail Caught Off An Oyster Farm – Brandon Smith

When targeting tripletail, anglers will typically sit at the highest point of the boat (some anglers have towers for spotting tripletail) and cruise along floating crab trap buoys, pilings, and sometimes oyster farms looking for Tripletail. These fish are very easily spooked, and a slow, quiet approach is best. Once in casting distance, toss your preferred bait (I typically want to have baby crabs or live shrimp when targeting tripletail) close to the floating structure, but not too close to spook the fish. You can usually watch the fish eat your bait (another added bonus) and once you set the hook, the fight is on! In the state of Florida, tripletail must be a minimum of 18 inches and there is a daily bag limit of 2 fish per person. Be very careful handling tripletail as they have very sharp dorsal and anal fins and their operculum (gill cover) is also very sharp with hidden spines.

So next time you’re out fishing and see something floating, make sure you give it a good look over. There might be a camouflaged tripletail that you can add to your fish box!

Tripletail Caught While Working Oyster Gear – Thomas Derbes

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 18, 2024

We are going to begin this series of articles with a “creature” that some do not consider alive – viruses. While studying marine science in college, and my early days as a marine science educator, there was a debate as to whether viruses were actually alive and should be included in a biology course. A quick glance at the textbooks of the time shows they were often omitted – though they were included in my microbiology class. Why were they omitted? Why did some consider them “non-living creatures”?

The coronavirus next to a strand of DNA.

Image: Florida International University.

Well, we always began biology 101 with the characteristics of life. Let’s scan these characteristics and see where viruses fit.

- Made of cells. This is not the case for viruses. A typical cell will include a cell membrane filled with cytoplasm and a nucleus, which is filled with genetic material (chromosomes containing DNA and RNA). An examination of a virus you will find it is either DNA or RNA encapsulated in a protein coat. It is “nucleus-like” in nature. Most cells run between 10-20 microns in size. A typical nucleus within a mammal cell will run between 5-10 microns. A typical virus would be 0.1 microns – these are tiny things – MUCH smaller than a cell.

- Process energy. Nope – they do not. Most cells utilize energy during their metabolism. Viruses do not do this.

- Growth and development. Nope again. They “spread”, which we discuss in a moment, but they do not grow. We are now 0-3.

- Homeostasis. Homeostasis is the movement of material and environmental control to remain stable – and viruses do not do this.

- Respond to stimuli. Yes… here is one they do. Studies show that viruses do respond to their chemical and physical environment.

- Metabolism. As mentioned above, this would be a no.

- Adaptation. Studies show that through very rapid reproduction they can adapt to the changing environment they are in.

- Reproduce. This is a sort of “yes/no” answer. They do reproduce (as we say – “spread”) but they do not do this on their own. They invade the nucleus within the cells of their host and replace their genetic material with that of the host creature. Then, during cell replication within the host, new viruses are produced and “spread”.

So, you can see why there is a debate. Of the eight common characteristics of life, viruses possess only three – and one of those can only be achieved with the assistance of a host creature. Now the question would be – do be labeled as a “creature” do you need ALL eight characteristics of life? Or only a few? And if only a few – how many? Because of this most biologists do not consider them alive.

During one class when we were discussing this a student made a comment – “don’t we KILL viruses? If so, then it must be alive first”. Point taken – and we should understand the phrase “kill a viruses” does not mean literally killing. It is a phrase we use. Though some argue we do kill viruses and thus…

Another point we could make here is that all life on the planet has been classified using a system developed by the Swedish botanist Carlos Linnaeus. Each creature is placed in a kingdom, then phylum, class, order, family, genus, and eventually a species name is given. We “name” the creature using its genus and species name – Homo sapiens for example. We do not see this for viruses.

All that said, both the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the National Institute of Health indicate the “most common form of life in the sea are viral-like particles” – with over 10 million in a single drop of seawater. We will leave the debate here. Your thoughts?

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.

As spring approaches, I’ve been receiving more calls from local pond owners looking for advice on preparing their farm ponds for the season. Managing a pond in the Florida Panhandle can be tricky—especially when dealing with spring-fed ponds. While these ponds are often beautifully clear, their constant water turnover makes management a challenge.