by Laura Tiu | Sep 13, 2024

Western Dune Lake Tour

Walton County in the Florida Panhandle has 26 miles of coastline dotted with 15 named coastal dune lakes. Coastal dune lakes are technically permanent bodies of water found within 2 miles of the coast. However, the Walton County dune lakes are a unique geographical feature found only in Madagascar, Australia, New Zealand, Oregon, and here in Walton County.

What makes these lakes unique is that they have an intermittent connection with the Gulf of Mexico through an outfall where Gulf water and freshwater flow back and forth depending on rainfall, storm surge and tides. This causes the water salinity of the lakes to vary significantly from fresh to saline depending on which way the water is flowing. This diverse and distinctive environment hosts many plants and animals unique to this habitat.

There are several ways to enjoy our Coastal Dune Lakes for recreation. Activities include stand up paddle boarding, kayaking, or canoeing on the lakes located in State Parks. The lakes are popular birding and fishing spots and some offer nearby hiking trails.

The state park provides kayaks for exploring the dune lake at Topsail. It can be reached by hiking or a tram they provide.

Walton County has a county-led program to protect our coastal dune lakes. The Coastal Dune Lakes Advisory Board meets to discuss the county’s efforts to preserve the lakes and publicize the unique biological systems the lakes provide. Each year they sponsor events during October, Dune Lake Awareness month. This year, the Walton County Extension Office is hosting a Dune Lake Tour on October 17th. Registration will be available on Eventbrite starting September 17th. You can check out the Walton County Extension Facebook page for additional information.

by Carolina Baruzzi | Sep 13, 2024

Fall is not typically the season when we expect to see high plant activity, but in Florida’s longleaf pine savannas, fall thrive with colors. These unique ecosystems, characterized by their open canopy of towering longleaf pines and a diverse understory of grasses and wildflowers, are particularly beautiful in the fall, when seasonal flowering highlights the rich plant diversity that characterize these habitats (Figure 1).

Longleaf pine savanna flowering plants. Photo credits UF/IFAS communication

If you take a walk through longleaf pine savannas this season, you will likely notice several species of blazing star (Liatris spp.) standing out with tall, spiky clusters of purple flowers, which attract pollinators such as bees and butterflies. A similar plant, Florida paintbrush (Carphephorus corymbosus), also attracts predators. For example, you might spot lynx spiders camouflaged on top of paintbrush flowers, waiting to ambush unsuspecting insects (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Lynx spider on Florida paintbrush. Photo credit: Carolina Baruzzi

Another common fall bloomer is the goldenrod (Solidago spp.) with its characteristic cascading spikes of yellow flowers. A common misconception is that goldenrod flowers cause allergies; in reality, ragweed pollen is to blame in most cases. In fact, while ragweed relies on wind to disperse its light, abundant pollen, goldenrods are primarily insect-pollinated. This means that their pollen is larger and heavier, and they generally produce it in smaller quantities, so it doesn’t become airborne as easily.

Although less conspicuous, many native grasses also flower during the fall in longleaf pine savannas. For example, toothache grass (Ctenium aromaticum) often blooms in summer, but it produces its distinctive corkscrew-shaped spikes following seedfall in the fall. Wiregrass (Aristida beyrichiana), a common native grass species in these habitats, frequently flowers during this season and can also give us important indication on site management (Figure 3). In fact, its flowering is primarily fire-stimulated as it tends to produce flowers and seeds when burned during the early summer. Therefore, a sea of flowering wiregrass often indicates that a site was recently burned!

ongleaf pine savannas with wiregrass inflorescences. Photo credit: Carolina Baruzzi

Fall flowering in longleaf pine savannas is more than just a colorful seasonal change — it is a reminder of the ecological resilience and biodiversity of these systems. If you want to learn more, about the plant and wildlife they support, you can click on these additional resources below:

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 30, 2024

Introduction

The bay scallop (Argopecten irradians) was once common in the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system. However, by 1970 they were all but gone. Closely associated with seagrass, especially turtle grass (Thalassia testudinum), some suggested the decline was connected to the decline of seagrass beds in this part of the bay. Decline in water quality and overharvesting by humans may have also been a contributor. It was most likely a combination of these factors.

Scalloping is a popular activity in our state. It can be done with a simple mask and snorkel, in relatively shallow water, and is very family friendly. The decline witnessed in the lower Pensacola Bay system was witnessed in other estuaries along Florida’s Gulf coast as well. Today commercial harvest is banned, and recreational harvest is restricted to specific months and to the Big Bend region of the state. With the improvements in water quality and natural seagrass restoration, it is hoped that the bay scallop may return to lower Pensacola Bay.

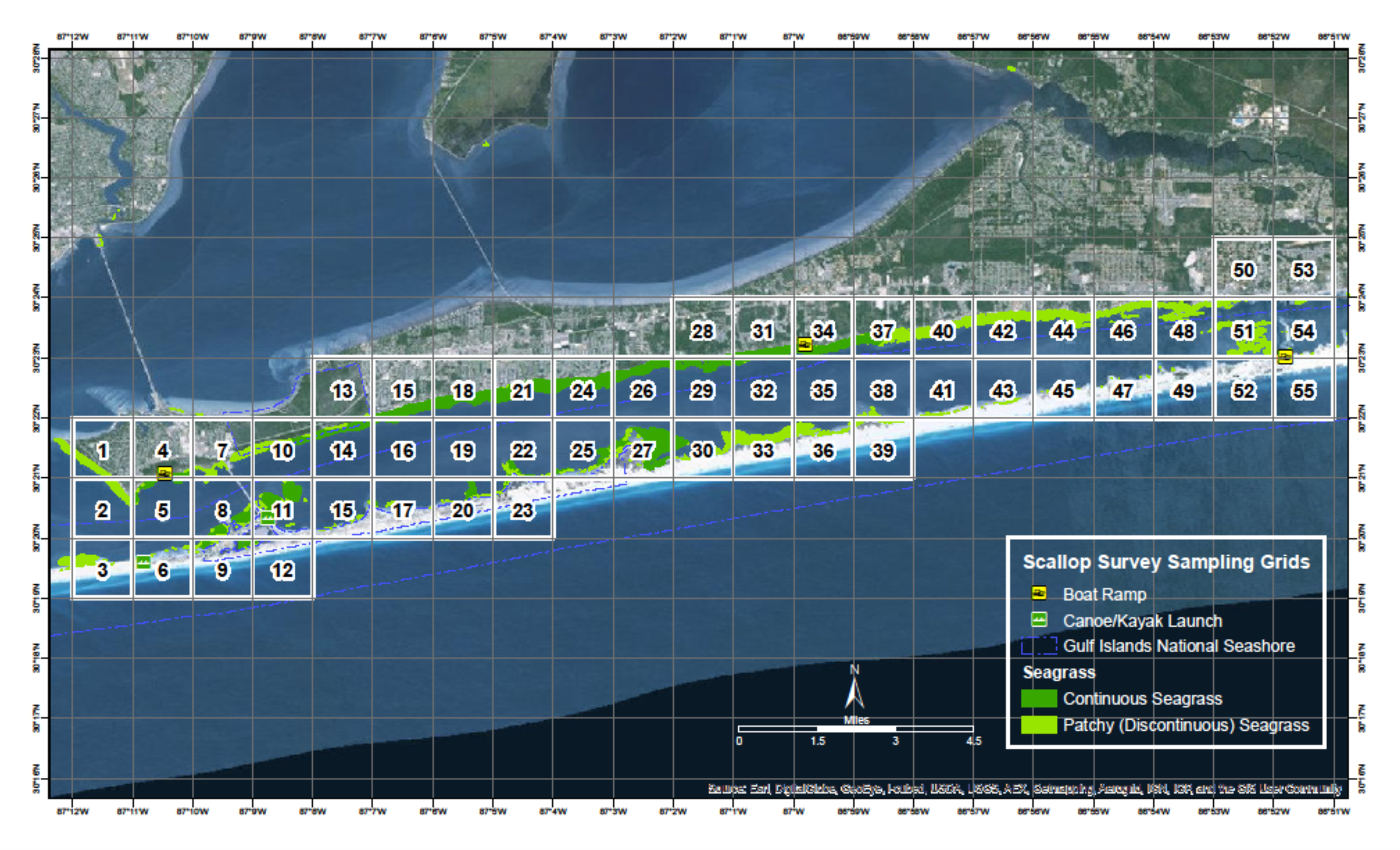

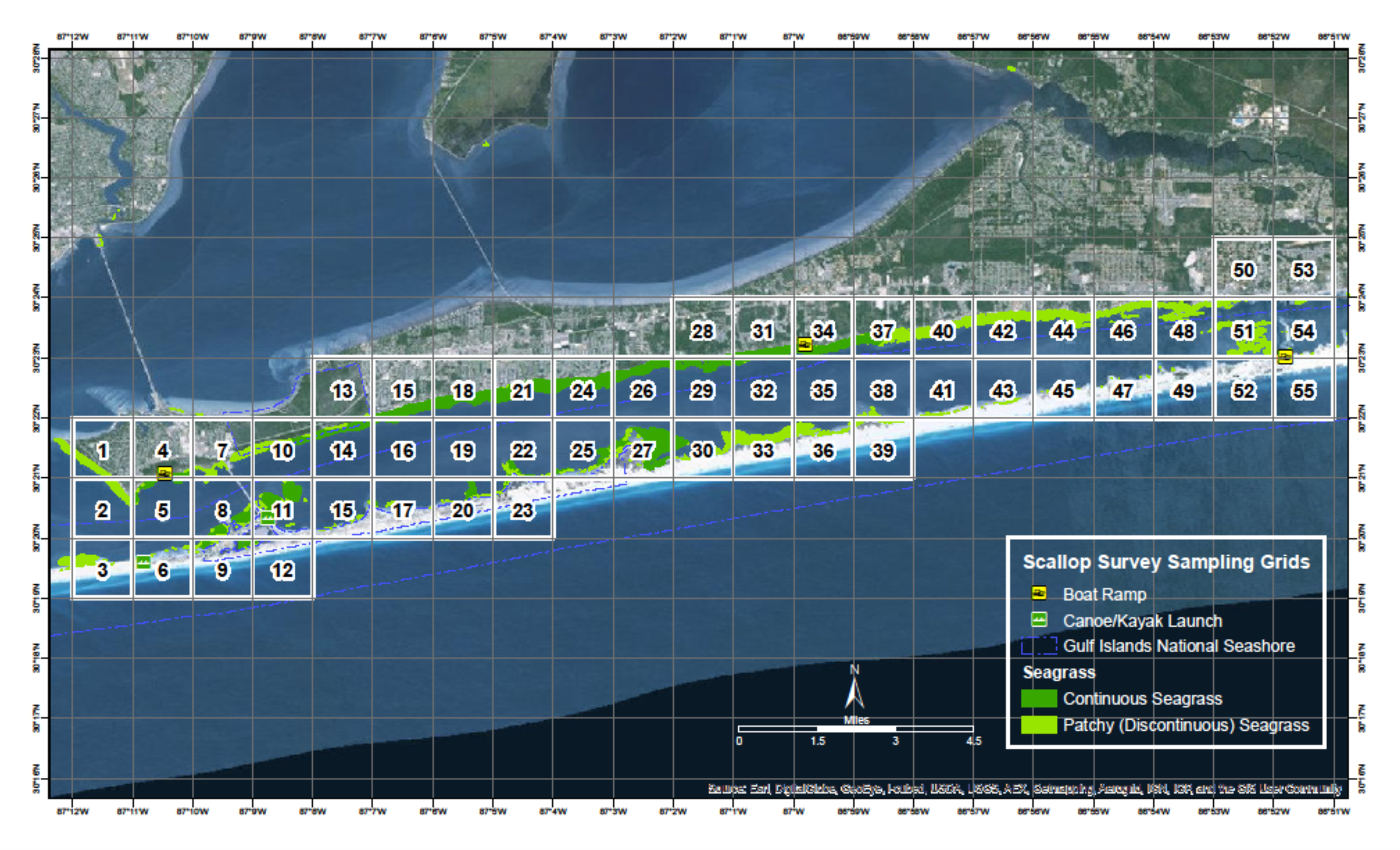

Since 2015 Florida Sea Grant has held the annual Pensacola Bay Scallop Search. Trained volunteers survey pre-determined grids within Big Lagoon and Santa Rosa Sound. Below is the report for both the 2024 survey and the overall results since 2015.

Methods

Scallop searchers are volunteers trained by Florida Sea Grant. Teams are made up of at least three members. Two snorkel while one is the data recorder. More than three can be on a team. Some pre-determined grids require a boat to access, others can be reached by paddle craft or on foot.

Once on site the volunteers extend a 50-meter transect line that is weighted on each end. Also attached is a white buoy to mark the end of the line. The two snorkelers survey the length of the transect, one on each side, using a 1-meter PVC pipe to determine where the area of the transect ends. This transect thus covers 100m2. The surveyors record the number of live scallops they find within this area, measure the height of the first five found in millimeters using a small caliper, which species of seagrass are within the transect, the percent coverage of the seagrass, whether macroalgae are present or not, and any other notes of interest – such as the presence of scallop shells or scallop predators (such as conchs and blue crabs). Three more transects are conducted within the grid before returning.

The Pensacola Scallop Search occurs during the month of July.

2024 Results

A record 168 volunteers surveyed 15 of the 66 1-nautical mile grids (23%) between Big Lagoon State Park and Navarre Beach. 152 transects (15,200m2) were surveyed logging 133 scallops. An additional 50 scallops were found outside the official transect for a total of 183 scallops for 2024.

2024 Big Lagoon Results

75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids (64%) within the Big Lagoon. 67 transects were conducted covering 6,700m2.

101 scallops were logged with an additional 42 found outside the official transects. This equates to 3.02 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs and conchs, both scallop predators, as well as some sea urchins. All three species of seagrass were found (Thalassia, Halodule, and Syringodium). Seagrass densities ranged from 5-100%. Macroalgae was present in six of the seven grids (86%) but was never abundant.

2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

93 volunteers surveyed 8 of the 55 grids (14%) in Santa Rosa Sound. 85 transects were conducted covering 8,500m2.

32 scallops were logged with an additional 8 found outside the official transects. This equates to 0.76 scallops/200m2. Scallop searchers reported blue crabs, conchs, and sand dollars. All three species of seagrass were found. Seagrass densities ranged from 50-100%. Macroalgae was present in five of the eight grids (62%) and was abundant in grids surveyed on the eastern end of the survey area.

2015 – 2024 Big Lagoon Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

33 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

47 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

16 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

28 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

17 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

16 |

1 |

0.12 |

| 2021 |

18 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

38 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2023 |

43 |

2 |

0.09 |

| 2024 |

67 |

101 |

3.02 |

| Big Lagoon Overall |

323 |

104 |

0.64 |

2015 – 2024 Santa Rosa Sound Results

| Year |

No. of Transects |

No. of Scallops |

Scallops/200m2 |

| 2015 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2016 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2017 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2018 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2019 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2020 |

01 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2021 |

20 |

0 |

0.00 |

| 2022 |

40 |

2 |

0.11 |

| 2023 |

28 |

2 |

0.14 |

| 2024 |

85 |

32 |

0.76 |

| Santa Rosa Sound Overall |

1731 |

36 |

0.42 |

1 Transects were conducted during these years but data for Santa Rosa Sound was logged by an intern with the Santa Rosa County Extension Office and is currently unavailable.

Discussion

Based on a Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute publication in 2018, the final criteria are used to classify scallop populations in Florida.

| Scallop Population / 200m2 |

Classification |

| 0-2 |

Collapsed |

| 2-20 |

Vulnerable |

| 20-200 |

Stable |

Based on this, over the last nine years we have surveyed, the populations in lower Pensacola Bay are still collapsed. However, you will notice that in 2024 the population in Big Lagoon moved from collapsed to vulnerable for this year alone.

There are some possible explanations for this.

- The survey effort in Big Lagoon was stronger than Santa Rosa Sound. 75 volunteers surveyed 7 of the 11 grids. This equates to 11 volunteers / grid surveyed and 64% of the survey area was covered. With Santa Rosa Sound there were 93 volunteers who surveyed 8 of the 55 grids. This equates to 12 volunteers / grid surveyed but only 14% of the survey area was covered. Most of the SRS grids surveyed were in the Gulf Breeze/Pensacola Beach area. More effort east of Big Sabine may yield more scallops found.

- There is the possibility of different teams counting the same scallops. Each grid is 1-nautical mile, so the probability of one team laying their transect over an area another team did is low, but not zero.

- It is known that scallops have periodic population booms. Our search this year may have witnessed this. We will know if encounters significantly decrease in 2025.

Whether there was double counting this year or not, the frequency of encounter was much higher than in previous years. There were multiple reports from the public on social media about scallop encounters as well, and in some places we did not survey. It is also understood that scallops mass spawn. So, high density populations are required for reproductive success. The “boom” we witnessed this year suggests that there is a population of scallops – albeit a collapsed one – in our bay. It is important for locals NOT to harvest scallops from either body of water. First, it is illegal. Second, any chance of recovering this lost population will be lost if the adult population densities are not high enough for reproductive success.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank ALL 168 volunteers who surveyed this year. We obviously could not have done this without you.

Below are the “team captains”.

Harbor Amiss Glen Grant Eric Stone

David Anderson Phil Harter Neil Tucker

Laura Baker Gina Hertz Christian Wagley

Melinda Bennett Sean Hickey Jaden Wielhouwer

Samantha Bergeron (USM class) John Imhof Keith Wilkins

Cheri Bone Jason Mellos Christy Woodring

Cindi Cagle Greg Patterson

Cher Clary Kelly Rysula

A team of scallop searchers celebrates after finding a few scallops in Pensacola Bay.

Volunteer measures a scallop he found. Photo: Abby Nonnenmacher

Rick O’Connor Florida Sea Grant; Escambia County

Thomas Derbes II Florida Sea Grant; Santa Rosa County

by Laura Tiu | Aug 10, 2024

My son and his girlfriend were visiting last week and wanted to go fishing. Since she had never been deep sea fishing before, we decided that the best course of action would be to take the short four-hour trip on one of Destin’s party boats.

Party boats, also known as a head boat, are typically large boats from 50 to 100 feet long. They can accommodate many anglers and are an economical choice for first-time anglers, small, and large groups. The boat we went on holds up to 60 anglers, has restrooms, and a galley with snacks and drinks, although you can also bring your own. The cost per angler is usually in the $75 – $100 range and trips can last 4, 6, 8, or 10 hours.

We purchased our tickets through the online website and checked in at the booth 30 minutes before we departed. Everyone gets on and finds a spot next to a fishing pole already placed in a holder on the railing. For the four-hour trip, it is about an hour ride out to the reefs. On the way out, the enthusiastic and ever helpful deckhands explain what is going to happen and pass out a solo cup of bait, usually squid and cut mackerel, to each angler. When you get to the reef, you bait your hooks (two per rod) and the captain says, “start fishing.”

The rods are a bit heavy and there are some tricks you need to learn to correctly drop your bait 100 feet to the bottom of the Gulf. The deckhands are nearby to help any beginners and soon everyone is baiting, dropping, and reeling on their own. There are a few hazards like a sharp hook while baiting, crossing with your neighbor’s line and getting tangled, and the worst one, creating a “birds nest” by not correctly dropping your line. Nothing the deckhands can’t help with.

When you do finally catch a fish, you reel it up quickly and into the boat where a deckhand will measure it to make sure it’s a legal species and size and then use a de-hooker to place the fish in your bucket. After about 30 to 40 minutes, the captain will tell everyone to reel up before proceeding to another reef. At this time, you take your fish to the back of the boat where the deckhands put your fish on a numbered stringer and on ice.

For the four-hour trip, we fished two reefs. We had a lucky day with the three of us catching a total of 16 vermillion snapper, the most popular fish caught on Destin party boats. It’s a relaxing ride back to the harbor during which the deckhands pass the bucket to collect any tips. The recommended tip is 15-20% of your ticket price. These folks work hard and exclusively for tips, so if you had a good time, tip generously.

Once back in the harbor, your stringer of fish is placed on a board with everyone’s catch and they take the time for anyone that wants to get some pictures with the catch. Then, you can load your fish into your cooler, or the deckhands will clean your fish for you for another tip. If you get your fish filleted, you can take them to several local restaurants that will cook your catch for you along with some fries, hush puppies and coleslaw. It is an awesome way to end your day.

A happy angler after a party boat excursion.

by Mark Mauldin | Aug 2, 2024

All graphics and information included are courtesy of myfwc.com.

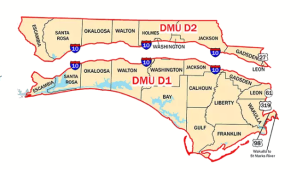

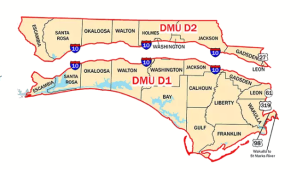

Here in the Panhandle (FWC Zone D), we are just under 3 months away from the October 26 opening day of archery season. As we move through summer and into the home stretch of hunting season preparations it is important to be sure all hunters understand the current regulations related to deer hunting in our area – it’s more complicated than it used to be.

Deer Management Unit map.

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/ Click on image to make larger.

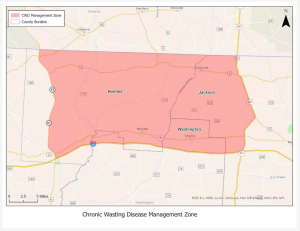

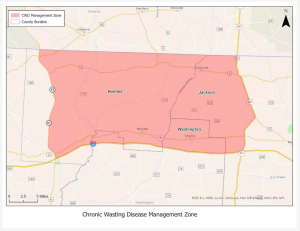

Following last summer’s discovery of Chronic Wasting Disease in Holmes County, the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone and its modified regulations will remain in place for the 2024-25 hunting season, but with some notable changes. The entirety of the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone lies within Deer Management Unit (DMU) D2. DMU-D2 is the portion of Zone D which lies north of I-10. As such, there are now some considerable differences in the hunting regulations north and south of I-10. For those of us who live along the I-10 corridor and who have opportunities to hunt on both sides of the interstate this could prove a bit confusing. The following is a discussion of the new regulations and how they differ by DMU.

New for the 2024-25 Hunting Season

The feeding of deer within the CWD Management Zone shall be allowed only during the deer hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025). This regulation is specific to the CWD Management Zone, not all of DMU-D2. Anywhere in Florida outside of the CWD Management Zone feeding stations must be continuously maintained with feed for at least 6 months before they are hunted over. So, unless you are hunting inside the CWD Management Zone, I hope your feeders have already been up and running for quite a while.

Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone From: https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/white-tail-deer/cwd/ Click on image to make larger.

The take of antlerless deer shall be allowed during the entire deer season in Deer Management Unit D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. For all of DMU-D2 there are no “doe days”. If it is hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025), it is legal to harvest antlerless deer in DMU-D2. This is quite different south of I-10, in DMU-D1, where antlerless deer may only be harvested during archery /crossbow season (Oct. 26 – Nov. 27), youth deer hunt weekend* (Dec. 7–8), and specific dates during general gun season (Nov. 30 – Dec. 1, Dec. 28–29).

Up to three antlerless deer, as part of the statewide annual bag limit of five, may be taken in DMU D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. Outside of DMU-D2, there can be no more than 2 antlerless deer included in the annual bag limit of five deer. Event if you hunt outside of DMU-D2 you still have the opportunity to harvest 3 antlerless deer in the 2024-25 season, but at least one of them must be harvested in DMU-D2. The bag limit of 5 total deer remains in place for all DMUs.

All CWD management related regulations can be found here.

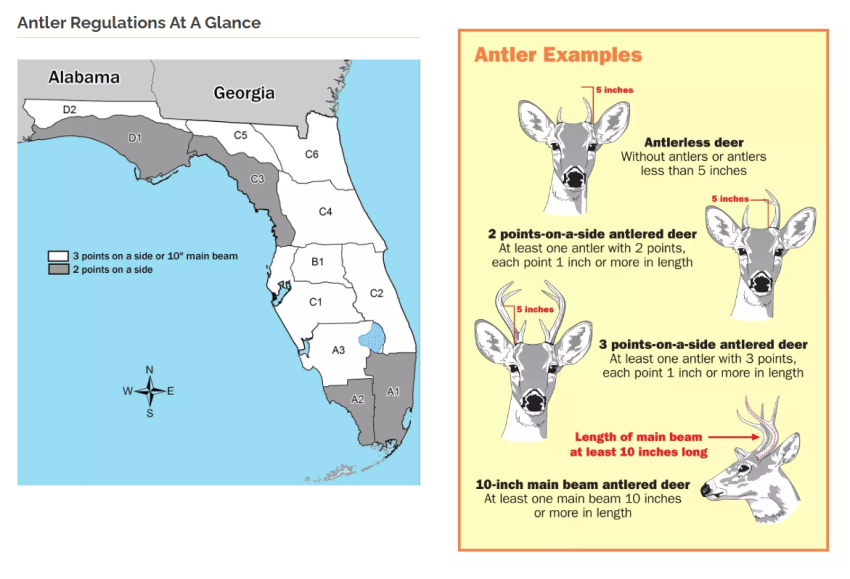

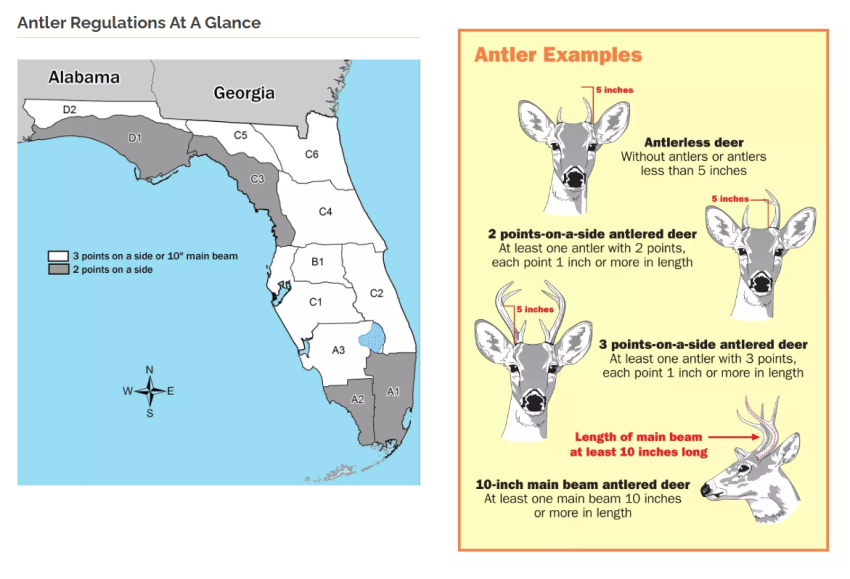

Antler Regulations

While it is not new this hunting season, it should be noted that there are different antler regulations north and south of I-10.

DMU-D1 (south of the intestate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with at least 2 points with each point measuring one inch or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

DMU-D2 (north of the interstate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with 1) at least 3 points with each point measuring one inch or more OR 2) a main beam length of 10 inches or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

In both DMU-D1 & D2 as part of their annual statewide antlered deer bag limit, youth 15-years-old and younger may harvest 1 deer annually not meeting antler criteria but having at least 1 antler 5 inches or more in length.

Florida Antler Regulations

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/

Harvest Reporting

Another somewhat new concept that some hunters still might not be accustomed to is Logging and Reporting Harvested Deer and Turkeys. All hunters must (Step 1) log their harvested deer and wild turkey prior to moving it from the point where the hunter located the harvested animal, and (Step 2) report their harvested deer and wild turkey within 24 hours.**

**Hunters must report harvested deer and wild turkey: 1) within 24 hours of harvest, or 2) prior to final processing, or 3) prior to the deer or wild turkey or any parts thereof being transferred to a meat processor or taxidermist, or 4) prior to the deer or wild turkey leaving the state, whichever occurs first.

Hunters have the following user-friendly options for logging and reporting their harvested deer and wild turkey:

Option A – Log and Report (Steps 1 and 2) on a mobile device with the FWC Fish|Hunt Florida App or at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com prior to moving the deer or wild turkey.

Option B – Log (Step 1) on a paper harvest log prior to moving the deer or wild turkey and then report (Step 2) at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com or Fish|Hunt Florida App or calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) within 24 hours.

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 28, 2024

One of several “flatfish” inhabiting our Panhandle coastal waters, the ocellated flounder (Ancylopsetta ommata) is one of the more striking species, in my opinion. From the four distinctive eye spots (ocelli) to its incredible variability in background patterns, I must just say that it is a beautiful creature. Flounders are unique among fish, in that early during larval development one eye will migrate over to join the other and the fish will orient to lay on its side when at rest. Only the top side will have coloration and the bottom side will be white. While the eyes end up on the same side, the pectoral and pelvic fins remain in their traditional positions, although the bottom-side pectoral fin is reduced in size.

Not the Biggest but Definitely one of the Coolest Flounder Species Around

Ocellated flounders are always left-eyed, meaning if you stood them up vertically with their pelvic fins down, the left side of the body has the eyes. When laying on the ocean floor, their independently moving eyes can keep a lookout in all directions. However, flounders tend to remain immobile when approached, depending on an awesome ability to camouflage themselves from predators. They can flip sand or gravel onto their top side which hides their outline and their ability to match the color and texture of the surrounding substrate is phenomenal.

This species is a fairly small fish, reaching lengths of about ten inches. However, they are by no means the smallest flatfish around. We also have hogchokers (a member of the sole family, 6-8 in.) and blackcheek tonguefish (to 9 in.). These are dwarfed by the larger Gulf flounder and Southern flounder which are highly prized table fare by fishers along our coasts and can reach sizes that earn them the nickname of “doormat” flounders. Regardless of the species of flounder you observe, it is unquestionably one of the super cool animals we have the privilege of living with here along the North Florida Gulf Coast.