by Mark Mauldin | Oct 21, 2025

Fall is here – peanuts are being picked and football season is in full swing. With fall being synonymous with the end of the growing season, it is a surprisingly good time of year to start many vegetation management operations. Fall is a particularly good time of year for a land manager to chemically control unwanted perennial vegetation.

–

General Comments & Caveats

I know plants can’t read calendars and to my knowledge they don’t watch football, so how would they even “know” it’s fall? Why does the season matter? In very general terms, perennial plants (those that live for many years) respond to shortening day length; the decreasing amount of sunlight stimulates the plants to begin storing more energy for the winter ahead. This process increases the downward flow (from leaves, towards roots and rhizomes, etc.) inside the plant. This phenomenon pairs very well with how systemic herbicides need to move within the plant to be effective. Put another way, again in very simplified terms, fall applications of systemic herbicides to perennial plants build on the plants’ natural processes associated with transitioning to winter dormancy and provide the herbicide with excellent access and opportunity to affect the plant.

While fall can be an excellent time to control perennial vegetation, taking advantage of this opportunity does require some additional attention to detail, as compared to mid-summer herbicide applications. For herbicides to work properly the chemical must be able to enter the plant and the plant must then be able to move herbicide though its xylem and phloem cells.

- In the fall it is not uncommon for it to become very dry. Drought stress can impede both necessary processes described above. Fall herbicide applications only work when adequate moisture is available.

–

- Foliar herbicides, like glyphosate, must enter a plant through a functional green leaf. At some point in the fall, the leaves of deciduous plants lose their functionality and thus their ability to convey herbicide to the rest of the plant. Chinese Tallow (popcorn tree) comes to mind here – if the leaves have changed color, they have been cut off from the rest of the plant making them useless for receiving herbicide.

–

- Cold temperatures (particularly below freezing) can cause plants to go dormant. Dormant plants do not circulate herbicide effectively. Plants vary greatly as to what temperature induces dormancy and how quickly they regain functionality after temperatures increase. When controlling perennial grasses, it is generally recommended to make fall applications before first frost and the browning of leaves that closely follows. For plants that retain green leaves after frost (privet, for example), make sure temperatures are well above freezing at the time of herbicide application.

NOW is the time to treat cogongrass – fall, with good soil moisture. Don’t miss this ideal window for herbicide application.

Photo Credit: Mark Mauldin

–

Specific Vegetation Management Practices to Consider this Fall

- Kill Cogongrass. Almost every year, about this time I write an article reminding folks that now is the best time of year to kill cogongrass. I won’t rewrite the article this year, I’ll just include links to previous iterations – see below. Cogongrass is bad, if it’s on your property kill it now. In my opinion, it is the most troublesome weed we have here in Northwest Florida. It is very difficult to control; so, you need to do everything you can to improve your chances of success. Spraying in the fall (not mid-summer) really helps.

–

- Control Trees and Brush. Fall and winter are excellent times of year to employ several different methods which allow you to apply herbicide directly to induvial woody plants with relatively little risk to surrounding desirable vegetation. While very effective, all these individual plant techniques are quite labor intensive, making the cooler temperatures associated with the fall perhaps more important to the applicator than the plant physiology and herbicide efficacy discussed earlier. Use these links to access videos that discuss each technique in detail.

–

Foliar applications (to the leaves) of herbicide to small trees and woody brush can be very effective in the fall, for the reasons mentioned earlier and provided all of the caveats mentioned earlier are accounted for. That said, foliar applications have their limitations and generally shouldn’t be used on trees over 8ft tall. Foliar applications also generally carry more risk of damage to surrounding desirable vegetation. All that said, there are times when there is no surrounding desirable vegetation – think about doing site prep for a silviculture planting or clearing an opening for a wildlife food plot planting. In these kinds of situations fall timed, broadcast, foliar applications of systemic herbicides can be highly effective.

During the fall and winter trees and woody brush can be controlled via a variety of highly selective techniques, including basal bark, hack-and-squirt, and cut stump treatments. Image Credit: IFAS CAIP

–

- Mow??? I very infrequently recommend mowing for weed control but if weeds have not already made seed (many already have), fall mowing can clean up open spaces while helping to lessen the seed bank available for next year’s crop of weeds. Granted, mowing is great for quick aesthetic benefit, but it must be timed correctly to provide any long term, meaningful vegetation management. Most perennial plants can and will recover after being mowed, so mowing them after they have made seed provides little lasting benefit. Along the same lines, annual plants naturally die after making seed making timing very important to providing any meaningful weed management.

–

Fall is always a busy time year, but between tailgate parties and trips to the pumpkin patch be sure to take advantage of the opportunities the season provides for the highly effective management of some otherwise very hard to control vegetation. If you have any questions or would like to discuss any of these concepts in more detail, please don’t hesitate to reach out to me directly at mdm83@ufl.edu or 850-638-6180.

by Carolina Baruzzi | Sep 13, 2024

Fall is not typically the season when we expect to see high plant activity, but in Florida’s longleaf pine savannas, fall thrive with colors. These unique ecosystems, characterized by their open canopy of towering longleaf pines and a diverse understory of grasses and wildflowers, are particularly beautiful in the fall, when seasonal flowering highlights the rich plant diversity that characterize these habitats (Figure 1).

Longleaf pine savanna flowering plants. Photo credits UF/IFAS communication

If you take a walk through longleaf pine savannas this season, you will likely notice several species of blazing star (Liatris spp.) standing out with tall, spiky clusters of purple flowers, which attract pollinators such as bees and butterflies. A similar plant, Florida paintbrush (Carphephorus corymbosus), also attracts predators. For example, you might spot lynx spiders camouflaged on top of paintbrush flowers, waiting to ambush unsuspecting insects (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Lynx spider on Florida paintbrush. Photo credit: Carolina Baruzzi

Another common fall bloomer is the goldenrod (Solidago spp.) with its characteristic cascading spikes of yellow flowers. A common misconception is that goldenrod flowers cause allergies; in reality, ragweed pollen is to blame in most cases. In fact, while ragweed relies on wind to disperse its light, abundant pollen, goldenrods are primarily insect-pollinated. This means that their pollen is larger and heavier, and they generally produce it in smaller quantities, so it doesn’t become airborne as easily.

Although less conspicuous, many native grasses also flower during the fall in longleaf pine savannas. For example, toothache grass (Ctenium aromaticum) often blooms in summer, but it produces its distinctive corkscrew-shaped spikes following seedfall in the fall. Wiregrass (Aristida beyrichiana), a common native grass species in these habitats, frequently flowers during this season and can also give us important indication on site management (Figure 3). In fact, its flowering is primarily fire-stimulated as it tends to produce flowers and seeds when burned during the early summer. Therefore, a sea of flowering wiregrass often indicates that a site was recently burned!

ongleaf pine savannas with wiregrass inflorescences. Photo credit: Carolina Baruzzi

Fall flowering in longleaf pine savannas is more than just a colorful seasonal change — it is a reminder of the ecological resilience and biodiversity of these systems. If you want to learn more, about the plant and wildlife they support, you can click on these additional resources below:

by Ian Stone | Aug 30, 2024

How are the live oak (Quercus virginiana) and the history of the United States Navy linked? That is a very interesting question that actually led to the first forest reservation and planting project in the United States. That reservation and history is still alive and well here in the Florida Panhandle, preserved still today as the Naval Live Oaks area of Gulf Islands National Seashore. In our modern times it may not register what forest and wood resources had to do with national defense but in the 1700’s and 1800’s it was key. In the times of wooden sailing ships having a Navy was key to being a Great Power. To have a powerful navy a nation had to have wood and shipbuilding resources, which meant access to forests. The abundant forest resources of North America were a driving force for colonization, especially for the British. Building the Royal Navy into the most powerful at the time required a huge amount of resources, which the American Colonies had in abundance. When our nation won its independence, it was similarly a major asset for the United States as the U.S. Navy was built. The U.S. government quickly recognized that these resource needed to be maintained and reserved, particularly the live oak which was a major wood resource with a limited supply. This led to the first forest conservation measure, which was the establishment of Naval Live Oak Reservations along the Gulf Coast in the early 1800’s.

View from a high sand hill in Naval Live Oaks Gulf Breeze, FL Photo Credit: Ian Stone

Building sailing ships, required resources for the hull, masts, and waterproofing which all came from different trees and forest resources. Mast trees were in particularly high demand and usually were from particularly large and straight pines or spruce. This was a limited resource and the Eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) was a particularly good resource in North America. The southern pines were highly prized for production of naval stores which consisted of turpentine, tar, and rosin used for maintaining and waterproofing ships and their rigging. Oak was prized for hull construction, a live oak above the others. Live oak is exceeding strong and dense, one of the densest woods in North America. If you have ever experienced trying to split live oak for firewood you likely realize how hard it truly is. Axes and splitting wedges will bounce right off and barely crack a solid live oak log. It also grows in such a way that it was perfect for constructing the braces and complex hull components of ships. With these forest resources the United States had what it needed to begin building the United States Navy, a key component of national defense. In the War of 1812, the need for a strong Navy became readily apparent, and the U.S.S. Constitution would gain fame in its engagement with the Royal Navy on the open seas. U.S.S Constitution would get the nick name “Old Ironsides” from her strong live oak hull which appeared impervious to cannon shots during engagements. It is no wonder that the live oak resource was soon recognized as a critical need in expanding the Navy. President John Quincy Adams established the Naval Live Oak Reservation Program and in 1828 the Naval Live Oak Reservation was established in what is today Gulf Breeze, FL. Under the Department of the Navy a tree planting effort establishing young live oaks by planting acorns was established in the reserve. This made the Naval Live Oaks Reservation the first forestry preserve and one of the first managed forests in the United States. As with so many things it was national defense and the armed forces need for resources that lead to this program and reservation.

As live oak is a strictly North American species by the 1830’s the United States had near total control over this valuable resource. To ensure the resource was properly managed and not exhausted the Naval Live Oak Reservation system remained in place for nearly a century, with other reservations established along key areas along the Gulf and Atlantic Coasts. During this period almost all of the most significant live oak groves and resource was under Federal control for use in the building of naval ships. During the period through the civil war and just beyond this remained a critical resource for maintain Naval Power. By the start of the 20th century though wooden sailing ships had given way to steel steamers, and the live oak resource was no longer critical. In the early 1900’s many of the Naval Live Oak Reservations were returned to local governments, but the Naval Live Oaks remained in federal control. When the Gulf Islands National Seashore was created in 1971 it became part of that park under the National Park Service.

View of the Shoreline along the Naval Live Oaks Photo Credit: Ian Stone

Today you can go visit the Naval Live Oaks and experience the rich history as well as the pine and live oak forests that are part of the site. Unless you have done some history research or read some of the informational displays at the reservation the name may have been a bit puzzling. Today the forest resources at the Naval Live Oaks Reservation are not essential to our national defense. Live oak is now seldom used in lumber or other wood product applications and is largely ignored as a timber species. Today we can cherish this forest reservation for its conservation resources and the forest it preserves in an area that is heavily developed. It is a beautiful place to visit and hike, with a wonderful trail network both along the sandy hills and shorelines. You will need to have a Gulf Islands National Seashore pass as it is a fee area. It is well worth a visit to enjoy a unique forest ecosystem, which is truly unique historically. The natural beauty and habitat that the preserve covers are all due to the live oaks’ unique use in ship building during the age of sail. The live oak is a cherished and iconic tree in our region for many reasons, but when you visit the Naval Live Oaks consider the role it played in the development of the mighty United States Navy and our nation’s sea power in the era of wooden ships. While the original reason for the Naval Live Oak Reservation has past it still stands as a testament to the importance of forest resources to our nation nearly 200 years after it was founded.

by Ian Stone | May 10, 2024

Thinning is an important part of any forest management plan and getting it right can be the difference between successful outcomes and persistent problems. Probably one of the most common questions foresters get is “Should I Thin My Trees?”. It is an important question to ask and definitely needs a forester’s input to get right. Thinning is part of managing the density of a forest stand and preventing issues with overstocking. If a stand is overstocked it causes multiple issues with the health and growth of a forest stand. Forest stands can even stunt when left in overstocked conditions and fail to produce the timber yield that would be expected. Not thinning at proper intervals when it is needed also results in lost growth even if the thinning is performed later. The key issue is competition and managing density prevents excessive competition among trees. To understand how thinning works you must understand some of how trees grow.

An overstocked pine stand in need of thinning Santa Rosa County, FL . Photo Credit: Ian Stone

Trees compete on a site for resources such as sunlight, water, and nutrients. As a young stand of timber develops the trees initially have plenty of resources while they are young and small, but they begin to compete when they grow older. Initially the competition can be a good thing encouraging taller and straighter growth habits and self-pruning of lower branches. As the stand develops though the competition becomes a negative factor when the trees begin to experience stress from lack of resources, primarily sunlight but also nutrients and water. At this point the stand is considered overstocked and thinning will improve the health and growth of the trees. Effectively thinning removes trees that are not needed and will eventually be out-competed and die. This allows a landowner to make some timber revenue while improving growth and health down the road. The trees that remain after thinning no longer are overstocked and competing and respond with improved growth and health. This important forest management technique is one of the primary management decisions in timberland ownership.

Overstocked stands create multiple issues that cause negative outcomes. One of the primary issues is that trees in overstocked conditions are weaker and more susceptible to insect and disease outbreaks. It is very common for bark beetle outbreaks and other issues to take hold in overstocked stands and produce considerable losses. Thinning is an effective measure at preventing this. Overstocked conditions result in poor growth and can lead to a situation where trees have a low portion of living foliage. Once this occurs a stand can become locked in a slow growing condition that can’t be reversed. This causes a loss of both volume and quality by reducing the development of high value saw-timber and poles. Overstocked and dense stands are also less desirable for wildlife and plant diversity. Thinning opens up the forest and allows more light and space which improves habitat and increases diversity on the forest floor and lower levels. All around thinning at the right time based on the forest conditions and stocking produces better outcomes. During thinning trees with form, disease, or other issues can be removed to improve the overall stand. Determining when and how to thin is a function of having a good forest inventory and monitoring tree size and stocking. There is usually a period of time that is referred to as a “thinning window” when the stand is beginning to become overstocked but will still produce a thinning response. This varies based on forest conditions and is more of a function of the size and density of the trees than an exact age or predetermined point in time. The best practice is to determine when a forest is entering the thinning window and take advantage of the thinning benefits. Delaying thinning will result in less optimal outcomes and results may be permanent. Similarly thinning too early or thinning incorrectly (too few or too many trees removed) can produce less desirable results. The key is to thin correctly and thin when forest conditions indicate it is needed.

Overall thinning is one of the best forest improvement practices available, and to get the most benefit it has to be done correctly. Far too often forest areas that need thinning are overlooked and go far too long without getting the thinning they need. You do not want to look into getting your timber thinned only to find out you should have done it 5-8 years ago or more. Worse still you develop a southern pine beetle out break and loose timber or start to have timber die from competition. The best way to make sure you stay informed on when and to what extent to thin is to have a forest management plan and update it regularly. Working with a consulting forester to inventory your timber stand and plan out forest management is one of the best things you can do. A good consultant forester can assist you in determining when and how to thin properly. They can also assist in marketing timber harvested in a thinning along with other services like timber marking. You can get assistance through the County Forester office with Florida Forest Service as well. You can work with the County Forester to enroll in the Forest Stewardship Program and get a management plan written at no cost to you. A forest management plan will cover thinning and other important practices to help you meet your goals. Determining when and how to thin is something that requires advice from a good professional forester. By working with a professional forester, you will avoid common pitfalls like making opportunistic thinning decisions, over-thinning, under thinning, leaving poor quality trees, and more. If you think your stand may need thinning contact the extension office, the county forester, or a professional forester of your choice. Making those contacts are a great first step in getting the most out of a good thinning.

by Ian Stone | May 3, 2024

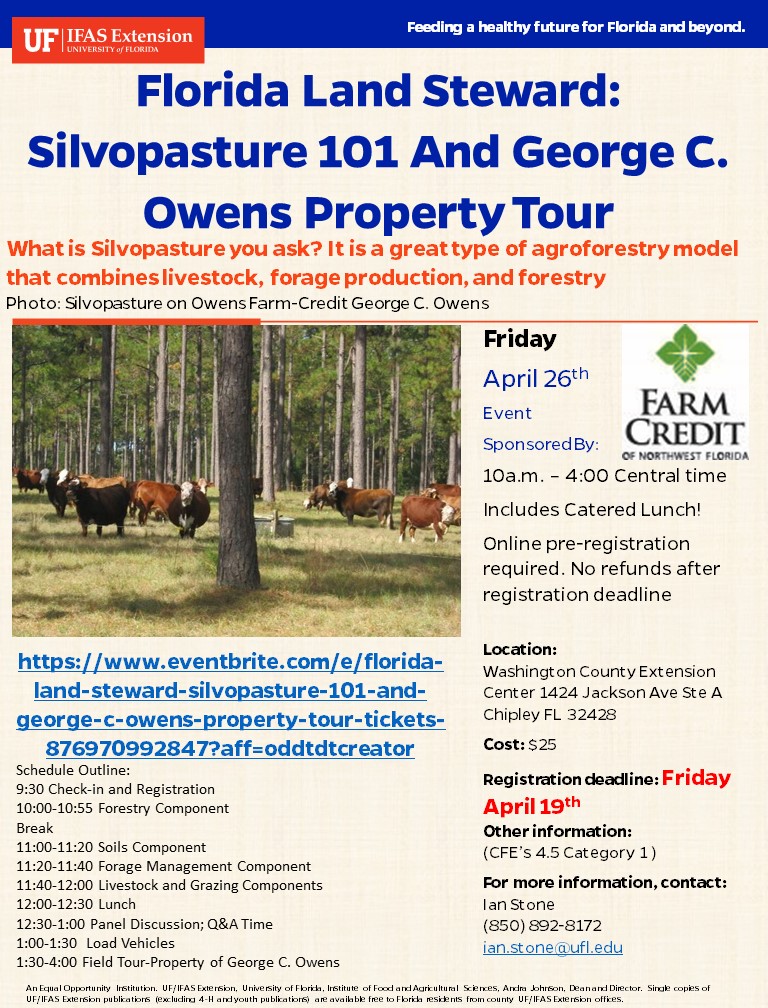

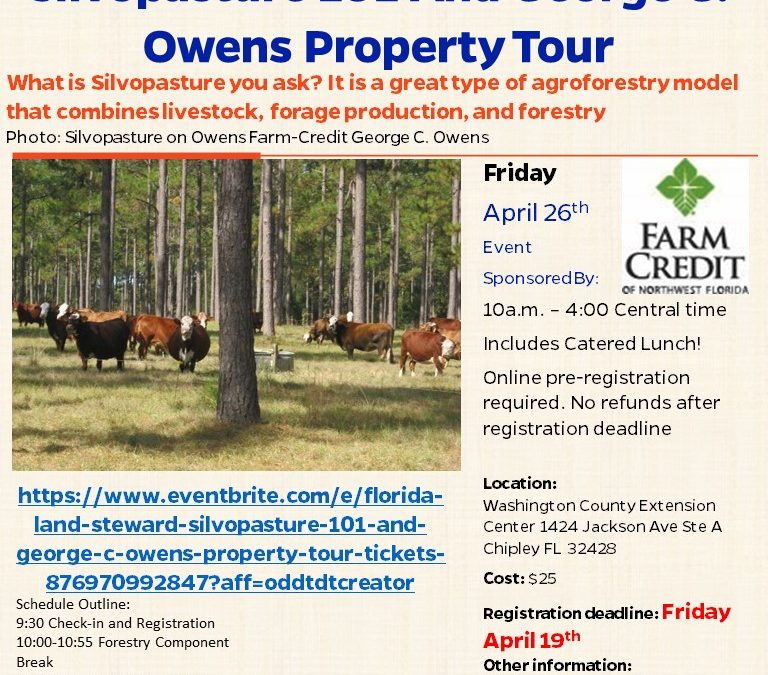

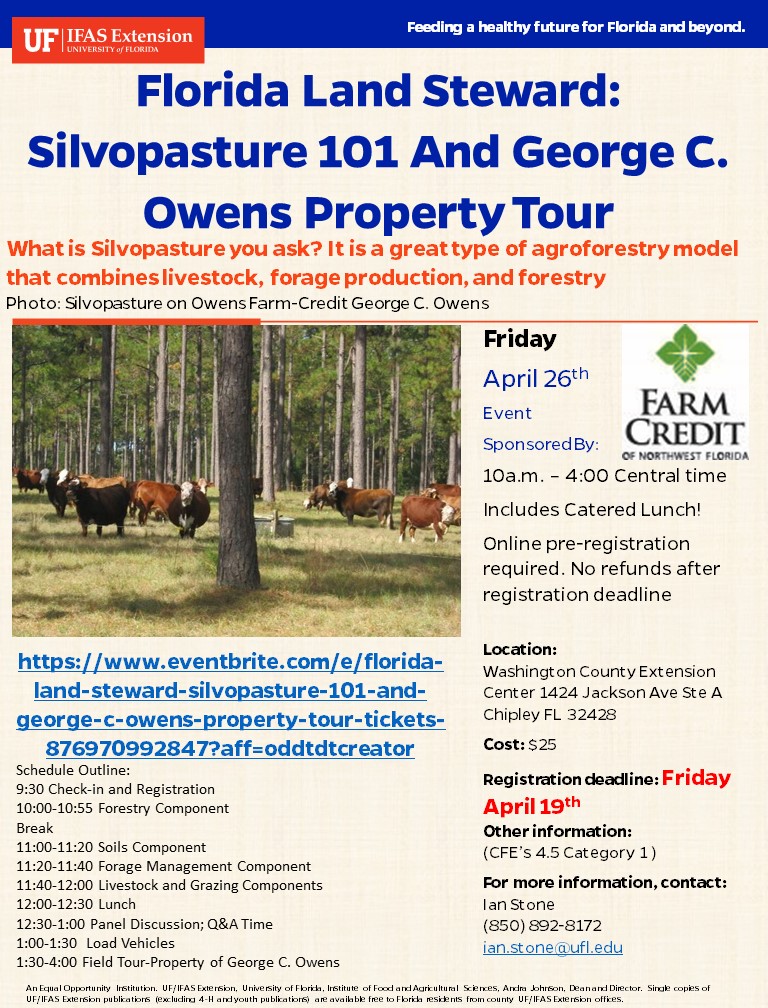

Forestry Agent Ian Stone Starts the Meeting and Teaches Participants about the Nuances of Timber Management in Silvopasture vs Traditional Timber Systems – Kacey Aukema

The UF/IFAS Extension Northwest District hosted a well-attended Silvopasture workshop and farm tour in Chipley on Friday April 26th. What exactly is silvopasture you may wonder? Ian Stone, the multi-county Forestry agent based in Walton County, did a great job in introducing the topic and overviewing how forestry management in silvopasture systems differ from more conventional timber systems in the first talk of the meeting. Silvopasture combines timber production and pasture production in the same area to allow for grazing animals to utilize the space in between tree and underneath tree rows for foraging. Silvopasture stands are much less dense than traditional stands of planted pines, to allow for adequate space for forage to grow and adequate sunlight to support forage growth. Implementing this kind of system can be achieved through thinning of an existing conventional timber stand “sIlvopasture by subtraction”, or intentionally planted in a density that would be conducive to forage production from the get-go. Ian’s presentation highlighted the attractive aspects of silvopasture production systems on how they facilitate multiple enterprises on one piece of property to diversify potential income streams, as well as the inherent constraints that these systems have when compared to timber or pasture/cattle production separately.

Okaloosa County Agriculture Agent Jennifer Bearden followed up Ian’s talk with a presentation on soils and soil management for silvopasture production. Depending on the tree species and forage species or variety optimal soil pH levels and fertilization needs may not line up perfectly for the grass vs. trees. Thus, proper soil testing to match the site with appropriate varieties and/or to guide how to amend the soil is important to balance the needs of the tree and forage crops being grown concurrently in these systems.

Cattle On The George And Pat Owens Property Are Rotated Between Conventional Pasture And Silvopasture Paddocks. – Kacey Aukema

Mark Mauldin, Washington County Interim Extension Director, and Nick Simmons Escambia County Extension Director also contributed with talks focusing on the interconnected topics of forage and livestock management in silovpasture systems. Not all forage varieties are well suited for the partial shaded environment and soil conditions that would be expected under silvopasture production. Therefore, picking the right species/variety for a particular site is important. Forage and livestock production in silvopasture systems often benefit from rotational grazing, therefore it is important to keep that in mind for pasture fencing and facilities planning to facilitate ease for rotating animals in and out of paddocks. One advantage of silvopasture systems for livestock and forages is from the partial shade provided by the trees. Shade reduces heat stress on the animals and can extend growth of some forages. For warm-season forages the partial cover provides a degree of frost protection, and for cool-season forages the shade provides cooler temps later into the spring.

A ~5 Year-Old Stand Of Pines Planted For Silvopasture Following Damage From Hurricane Michael Currently Being Grazed (Left), And A 20+ Year Old Silvopasture Stand (Right) – Kacey Aukema.

Following the speaker program the attendees visited several different sites in silvopasture on the property of Geroge Owens–a local farmer and respected expert in silvopasture in the Southeast. Mr. and Mrs. Owens presented the site history at various stands of different ages of timber, and expounded on the strategies and experience they had gained over the years in managing the trees, pasture, and cattle on their operation. This included the impact of Hurricane Michael on their farm in 2018 and recovery since then. George and his wife Pat shared a wealth of experience during the tour and answered questions that attendees had about implementing these kinds of systems on their own properties.

We thank The Owens’ for hosting us on their property. Also we are grateful for The Florida Land Steward Program and Farm Credit of NW FL for sponsoring this event organized by Ian Stone, Mark Mauldin, and Chris Demers (Florida Land Steward Program Coordinator). We hope to continue to offer more educational programs related to silvopasture into the future.

George and Pat Owens Share Their Wealth of Experience with a Group Touring Their Property – Kacey Aukema

To learn more about Silvopasture Systems for the Southeast see this great article from Mississippi State:

Silvopasture: Grazing Systems Can Add Value to Trees

Written By: Kacey Aukema, Agriculture Extension Agent in Walton County

by Ian Stone | Apr 13, 2024

Silvopasture is a unique and highly effective agroforestry technique that can be a great fit to accomplish some landowners’ land management and agricultural enterprise objectives. Agroforestry is a system which combines forest management and agricultural production systems to get synergistic effects that make both systems more sustainable and resilient. While these systems do not seek to optimize and maximize forestry or agricultural outputs the overall economic and total outputs are usually higher than stand alone traditional or forestry systems. They are also very ancient and many of the worlds oldest agricultural systems and methods would fall under the agroforestry umbrella now. Silvopasture is one unique expression of this method of combining forestry and agriculture. Silvopasture systems seek to combine forestry, forage production, and livestock on one area of land where all three combined make for a strong system of both shorter term agricultural production and longer term forest products production. For the right landowner and the right objectives it can be a perfect match.

Are you and your landholdings suited to Silvopasture? The best way to find out is consult with our outstanding extension agents and visit an outstanding Silvopasture system and producer to see it in the field. Fortunately, this month just this opportunity will be provided in Washington County at the extension office in Chipley, FL. The morning will feature a series of presentations and a discussion panel covering forestry, forage production, soil consideration, and livestock components of silvopasture systems. The presenters will consist of agents Ian Stone (Forestry Walton/ Multi-county), Mark Mauldin (Agriculture, Washington), Jenifer Bearden (Agriculture, Okaloosa), Nick Simmons (Agriculture, Escambia). The morning session will be followed by a catered lunch. For the afternoon the program will feature an outstanding tour of an advanced and well established silvopasture system, Mr. George C. Owens is a nationally recognized livestock producer and landowner who has successfully implemented silvopasture systems using a variety of methods. He has presented at conferences at the local, state, and national levels and is an outspoken advocate of silvopasture and sharing his knowledge and agricultural success his lands in silvopasture have produced. The tour will include the panel of agents for infield discussions and questions. UF-IFAS is very grateful to Mr. Owens for opening his property for this tour. The workshop is also approved for 4.5 Category 1 Continuing Forestry Education (CFE) credits for foresters and land managers needing continuing education. The program is part of the Florida Land Steward series for the year and the entire team looks forward to hosting landowners and land managers in from across the Panhandle at this event.

For more information please contact Ian Stone at the Walton Extension Office. Online registration will be through Eventbrite at the following link https://www.eventbrite.com/e/florida-land-steward-silvopasture-101-and-george-c-owens-property-tour-tickets-876970992847?aff=ebdssbdestsearch . Online registration is required and the registration deadline is April 19th. Tickets are limited so please register early to ensure you have a ticket for the event. The team hopes to see those interested on April 26th and looks forward to showcasing how silvopasture can be part of your land management to meet your objectives. Mark your calendars and register early to ensure you can attend this educational and field tour opportunity.